In the era of Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hulu, it’s difficult to explain to youngsters of 2015 how the children of the 1970s and early 1980s — pre-VCR — sometimes spent hours attempting to recreate the experience of watching a beloved film again through other available means such as board games, “novelizations,” building model kits, trading cards, and perhaps most memorably of all: the photonovel.

The photonovel as a printed form arrived in the mid-1970s, just as Star Trek was reaching escape velocity in syndication and Star Wars was on the horizon. A number of different publishers, including Pocket Books, Mandala (Bantam), and Fotonovel Publications began releasing this new style of book; one which features hundreds of still images from the featured film, arranged in chronological/story sequence, with dialogue sometimes featured as comic-book-styled balloons.

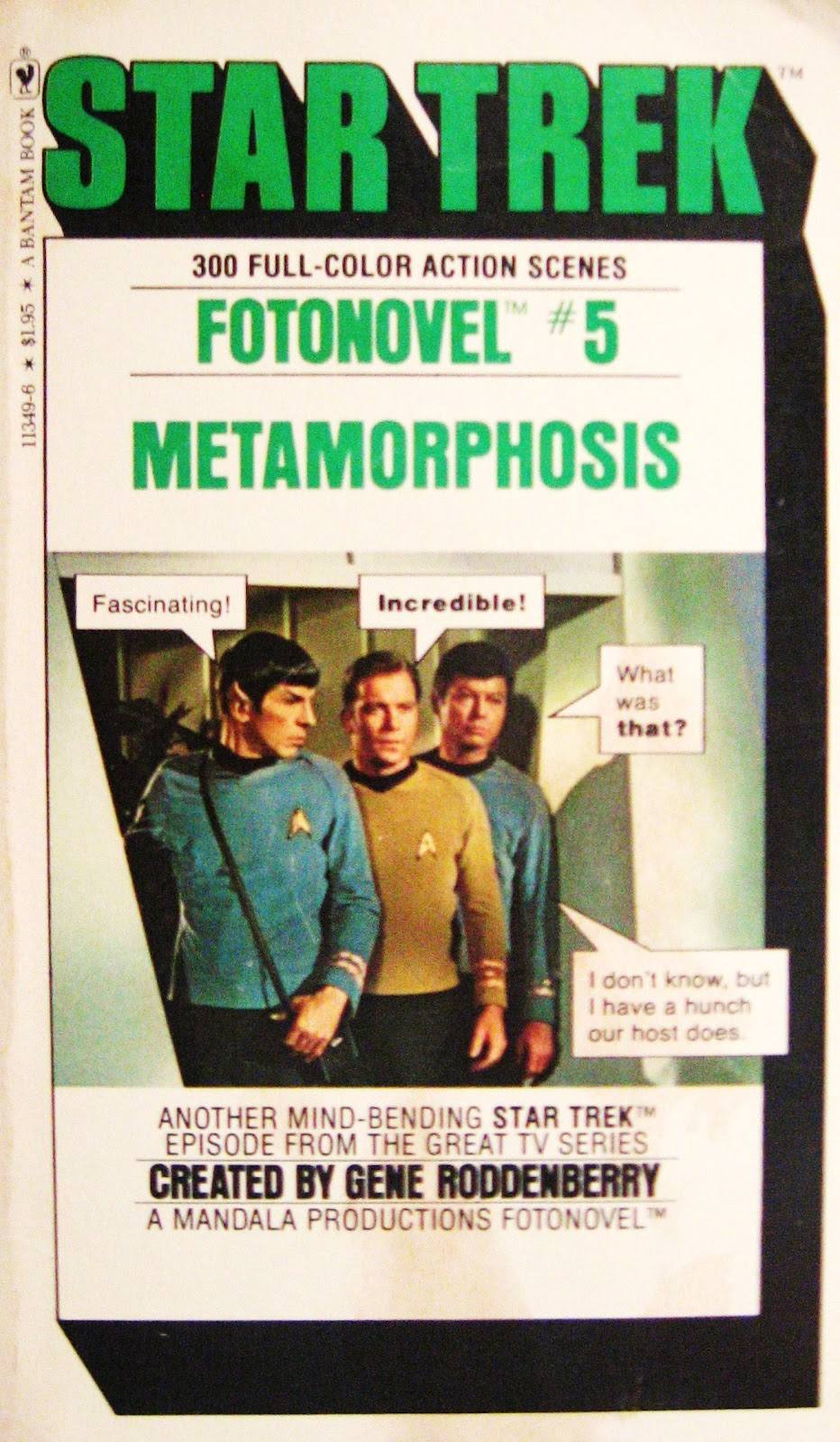

Some of the most beautiful Fotonovels painstakingly recreated beloved Star Trek episodes. Installments such as “City on The Edge of Forever,” “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” “A Piece of the Action,” “The Galileo Seven,” “Metamorphosis” and “Day of the Dove” were all adapted to this format. The fotonovels were billed (on the back cover of each installment) as “an authentic recreation of an astonishing voyage of the starship Enterprise” featuring “over 300 action photographs from the episode…”

These “fotonovels” also featured interviews with series guest stars (such as Mariette Hartley), a detailed cast-list (accompanied by photos) and even a glossary (which would feature terminology such as “atavachron.”)

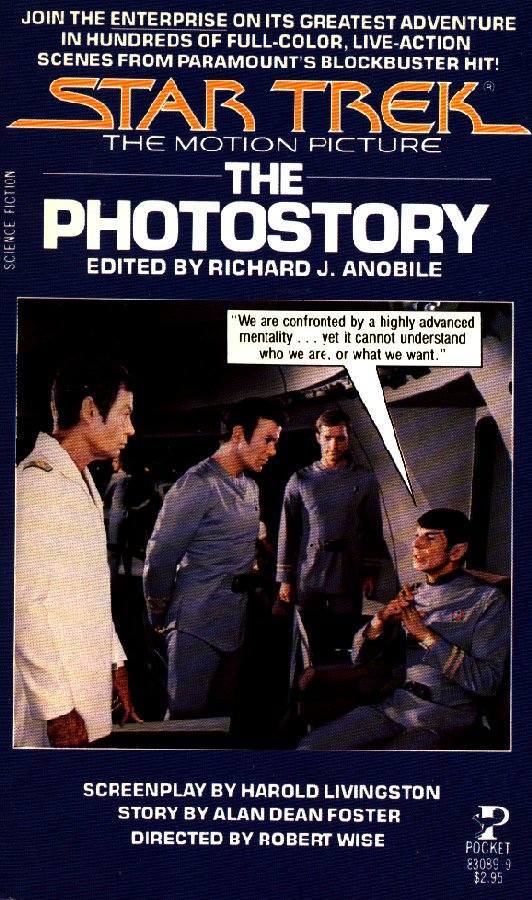

When Star Trek became a film franchise, Pocket Books published a “Photostory” of the first two films, The Motion Picture (1979) and The Wrath of Khan (1982). The Motion Picture Photostory was produced in glorious color, and captured the artistry and special effects majesty of the film.

By contrast, The Wrath of Khan photostory was a much cheaper affair with all black-and-white photos. Also, a considerable number of books from the first run had pages printed out of sequential order.

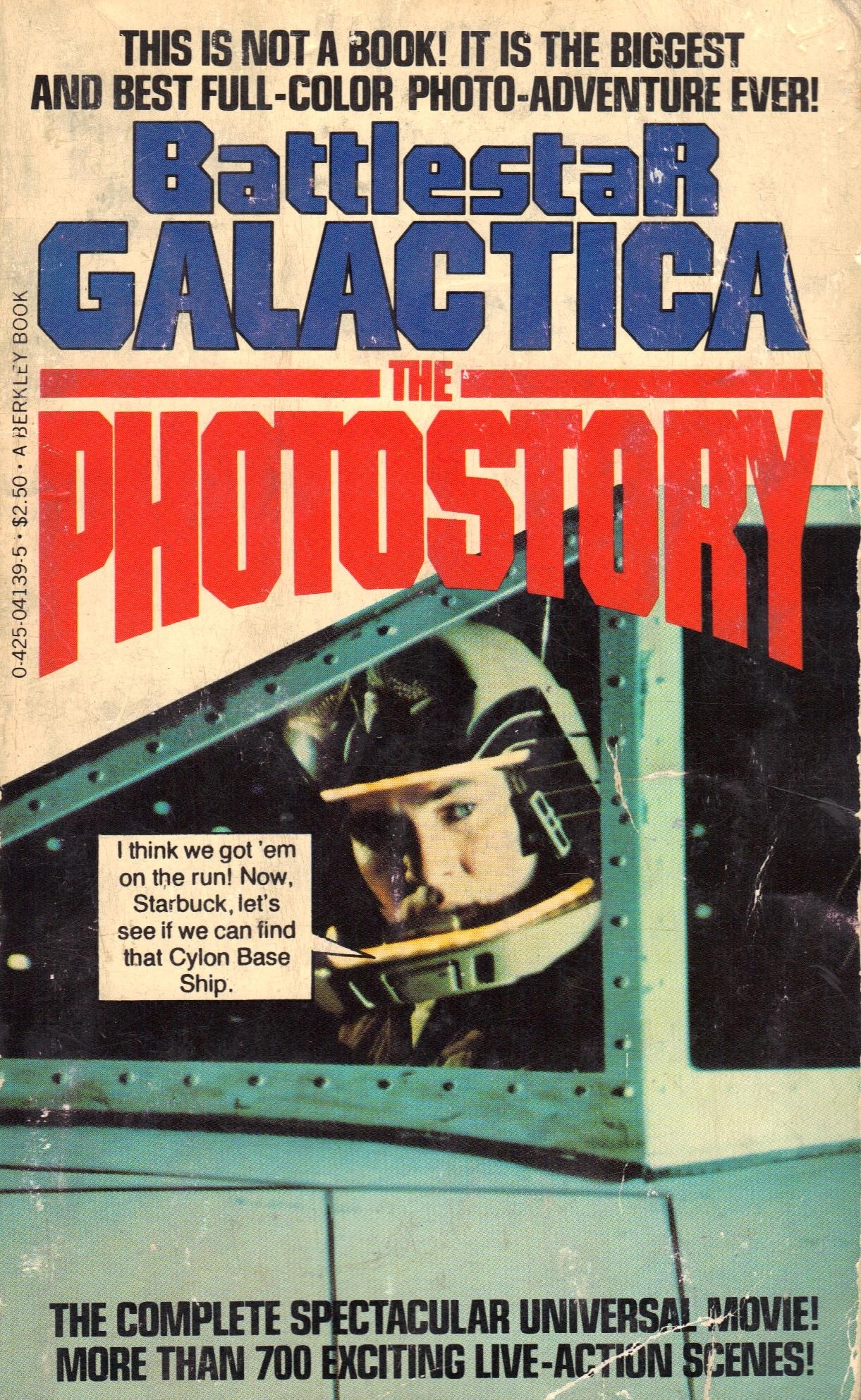

Outside of Star Trek, other new sci-fi productions of the day also were adapted to the popular photo format too. The Battlestar Galactica Photostory was advertised with the strange disclaimer: “This is not a book!” But the publication featured over 700 images from the premiere, three-hour installment of the series, “Saga of a Star World.”

Glen A. Larson’s later series, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979 – 1981) similarly was translated to Fotonovel form, with over “350 full color pictures directly from the film!” and “complete, original dialogue!”

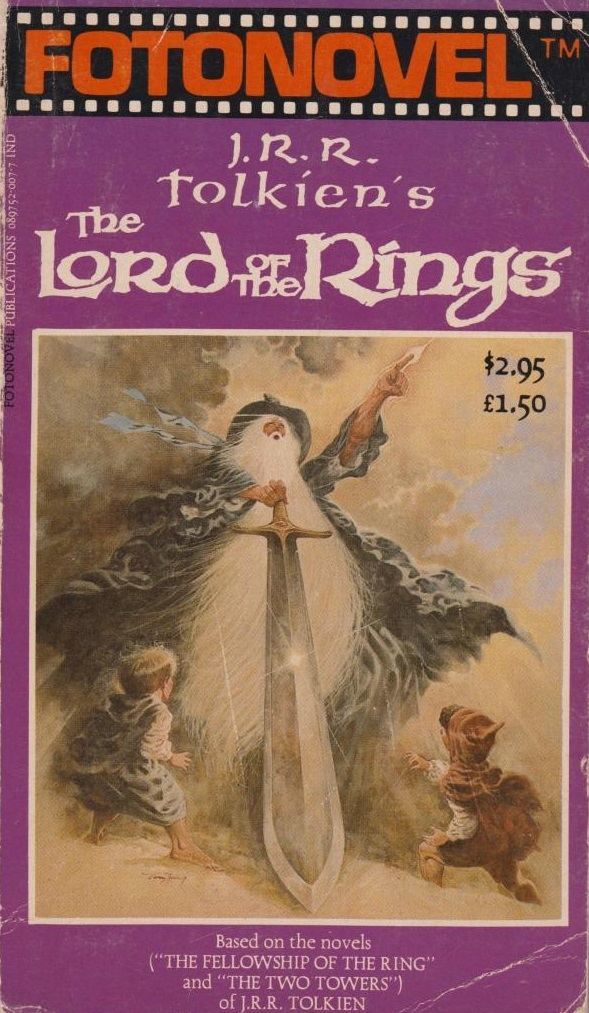

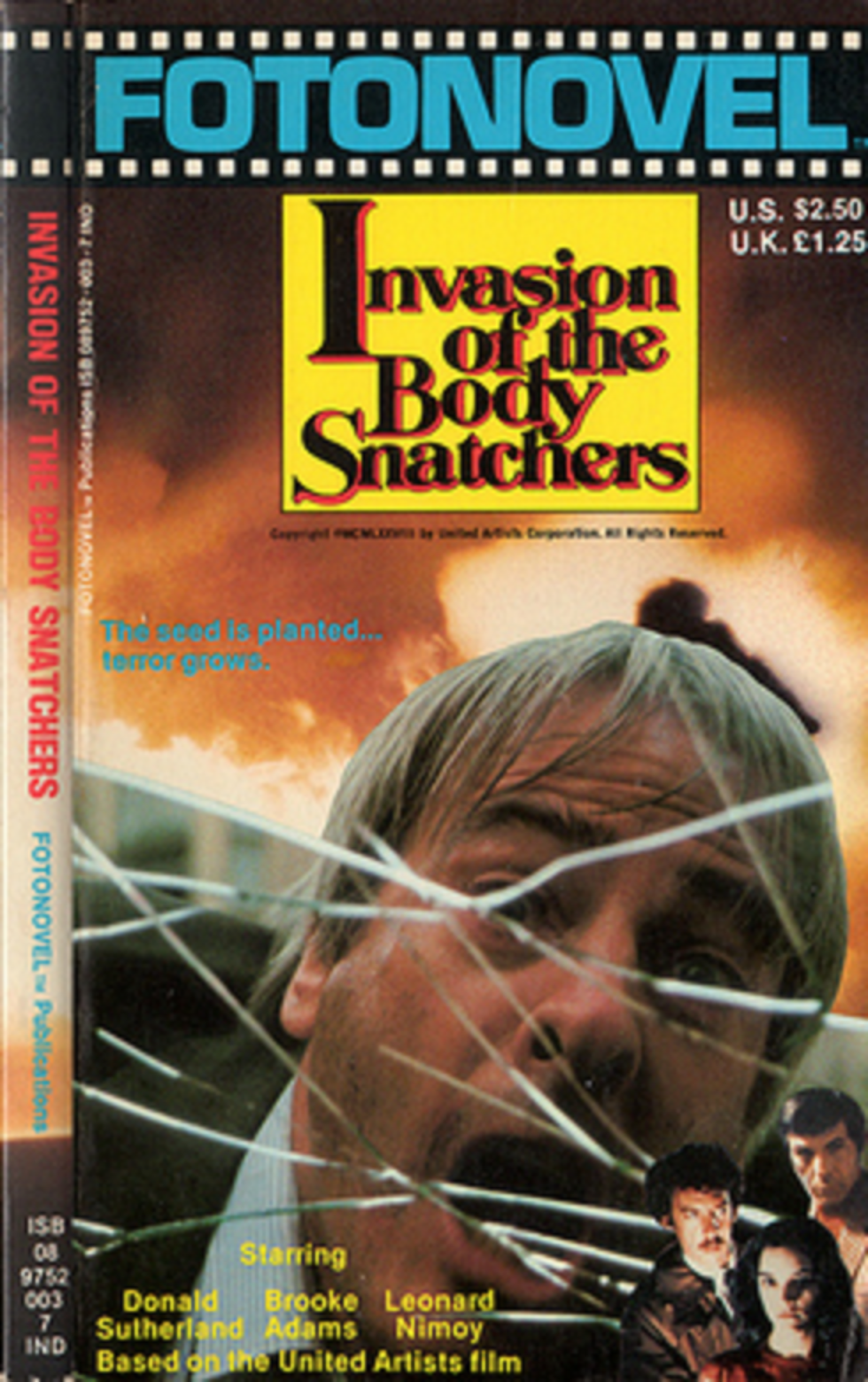

Although there are other genre Fotonovels, such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Lord of the Rings (1977), and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), they were all small, novel-sized editions.

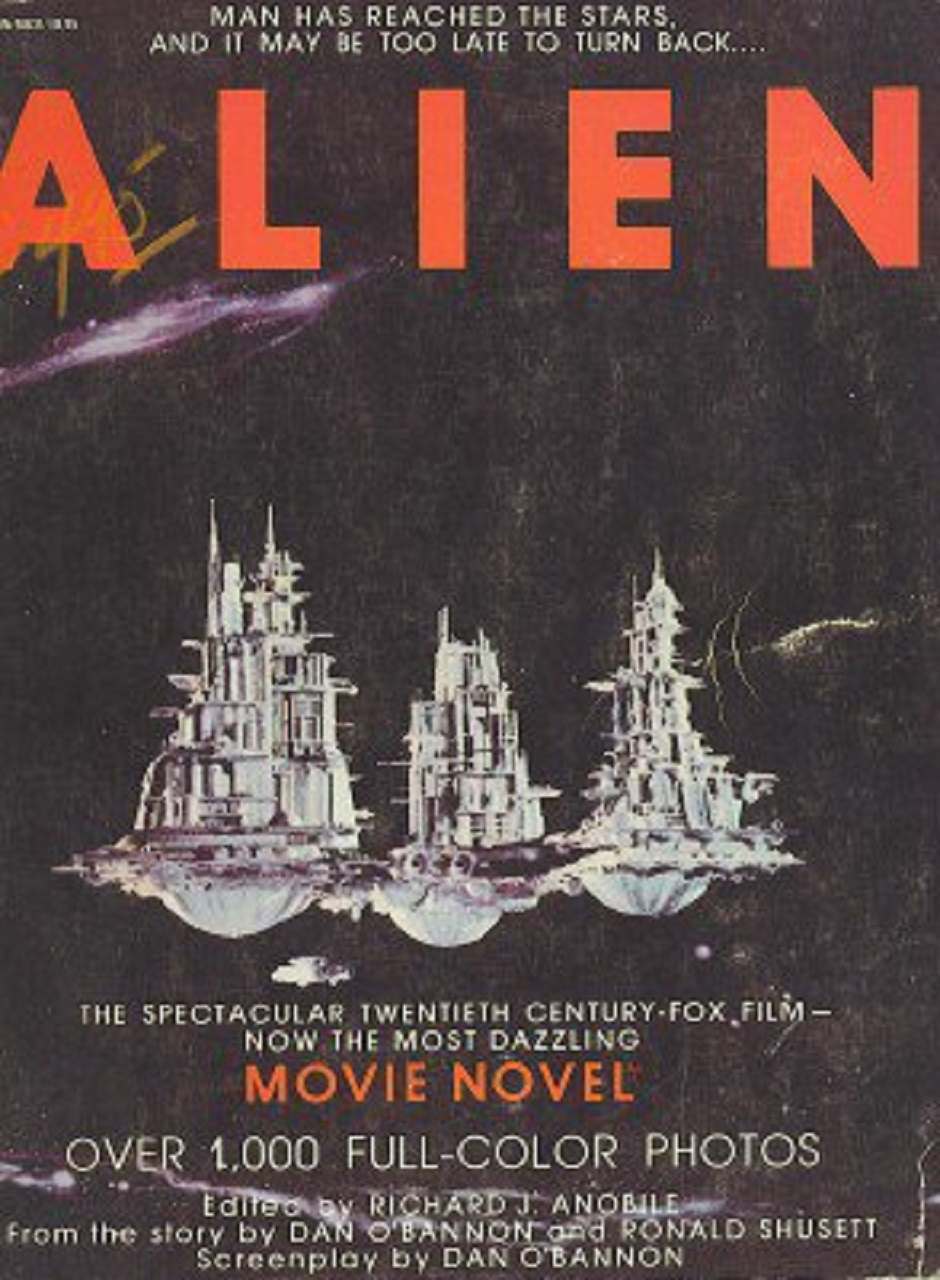

At least two films received grander treatment. Alien: The Movie Novel was billed as a “special edition photonovel” and was an over-sized book with a whopping 1,000 + photos from the Ridley Scott classic.. The Sean Connery space movie, Outland (1981) followed suit with a Warner Books entry featuring more than 750 photos.

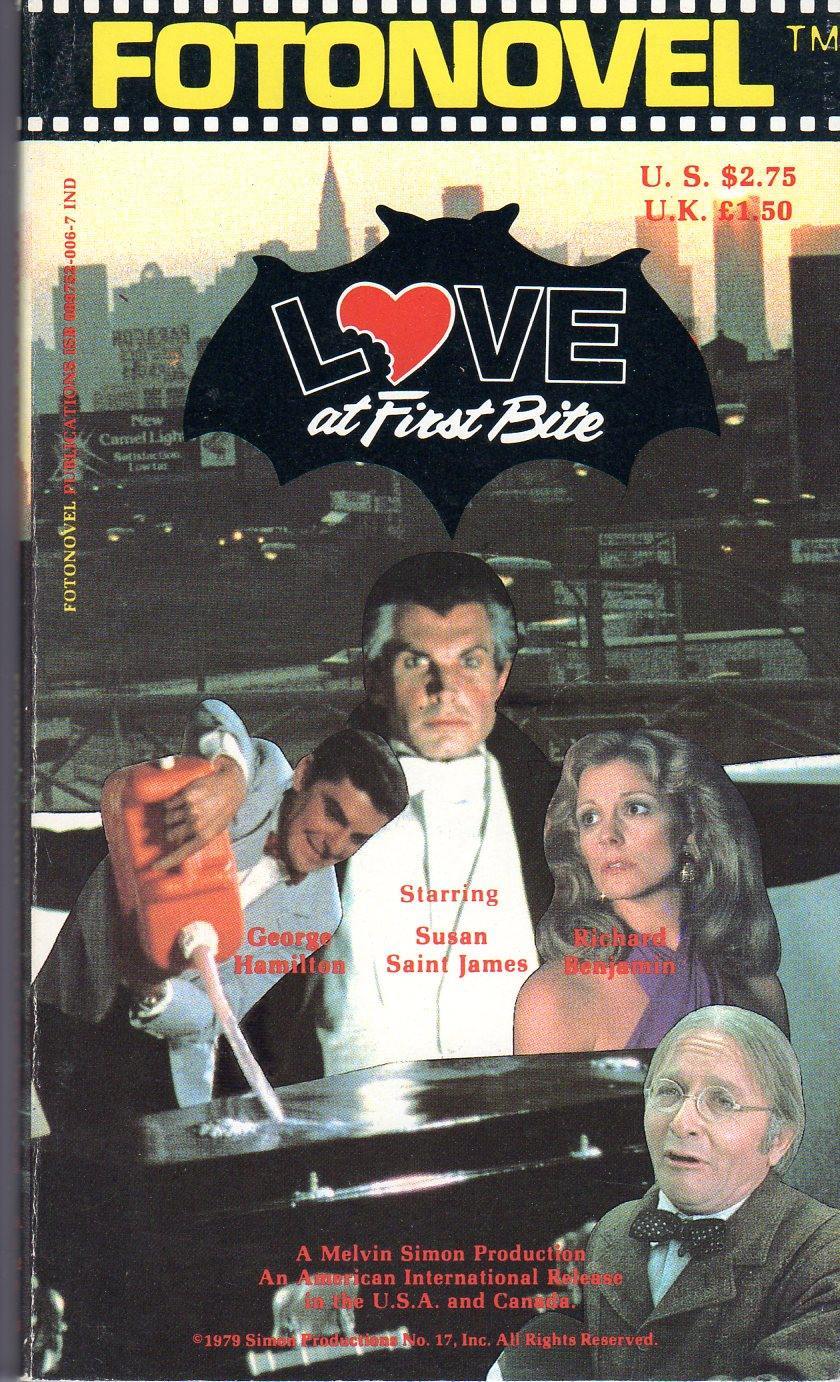

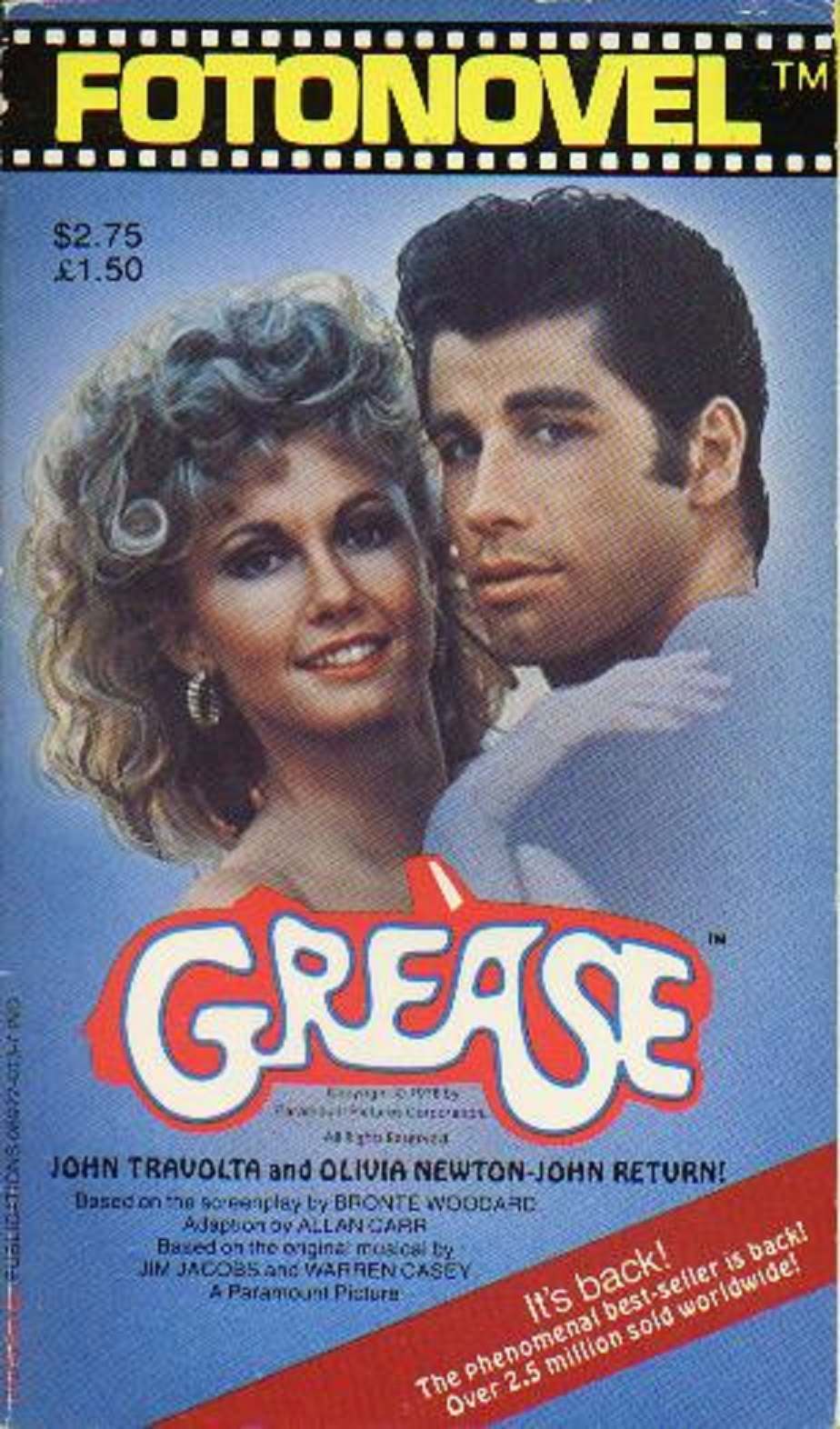

The science fiction genre was not the sole beneficiary of the photonovel trend of the period from roughly 1978 – 1981. Musicals such as Grease (1978) and Hair (1979) got the same treatment, as did comedies including Heaven Can Wait (1978), Revenge of the Pink Panther (1978) and Love at First Bite (1979). There was even, apparently, an Ice Castles (1978) photonovel.

Today, “fotonovels” remain widely beloved by the generation that grew up with them. Not just because they allowed audiences to relive productions they loved so dearly, but because they permitted the truly dedicated fan to get a closer look at sets, special effects, costumes and make-up of each production.

Similarly, burgeoning film scholars and historians could look, frame to frame at times, to see how certain shots were set-up or composed to express a visual story, or move a narrative forward. For all these reasons, the photonovel is a cherished collectible for many of us who came of age in the 1970s – 1980s.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.