“For me, trees have always been the most penetrating preachers”

– Herman Hesse, Wandering: Notes and Sketches

Hermann Hesse (July 2, 1877–August 9, 1962) speaks of the search for truth and that sense of escaping into the natural world in this 1920 collection of his pros, poetry and illustrations, Wandering: Notes and Sketches. The book follows the author’s contemplations through nature and the insights that transpired.

Written after a trip to the Alps, in Wandering Hesse crystallises what is is to be yourself and at once belong. On May 2, 1919, the author wrote to Romain Rolland (29 January 1866 – 30 December 1944) the French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915:

“I have had to bear a very heavy burden in my personal life in recent years. Now I am about to go to Ticino once again, to live for a while as a hermit in nature and in my work.”

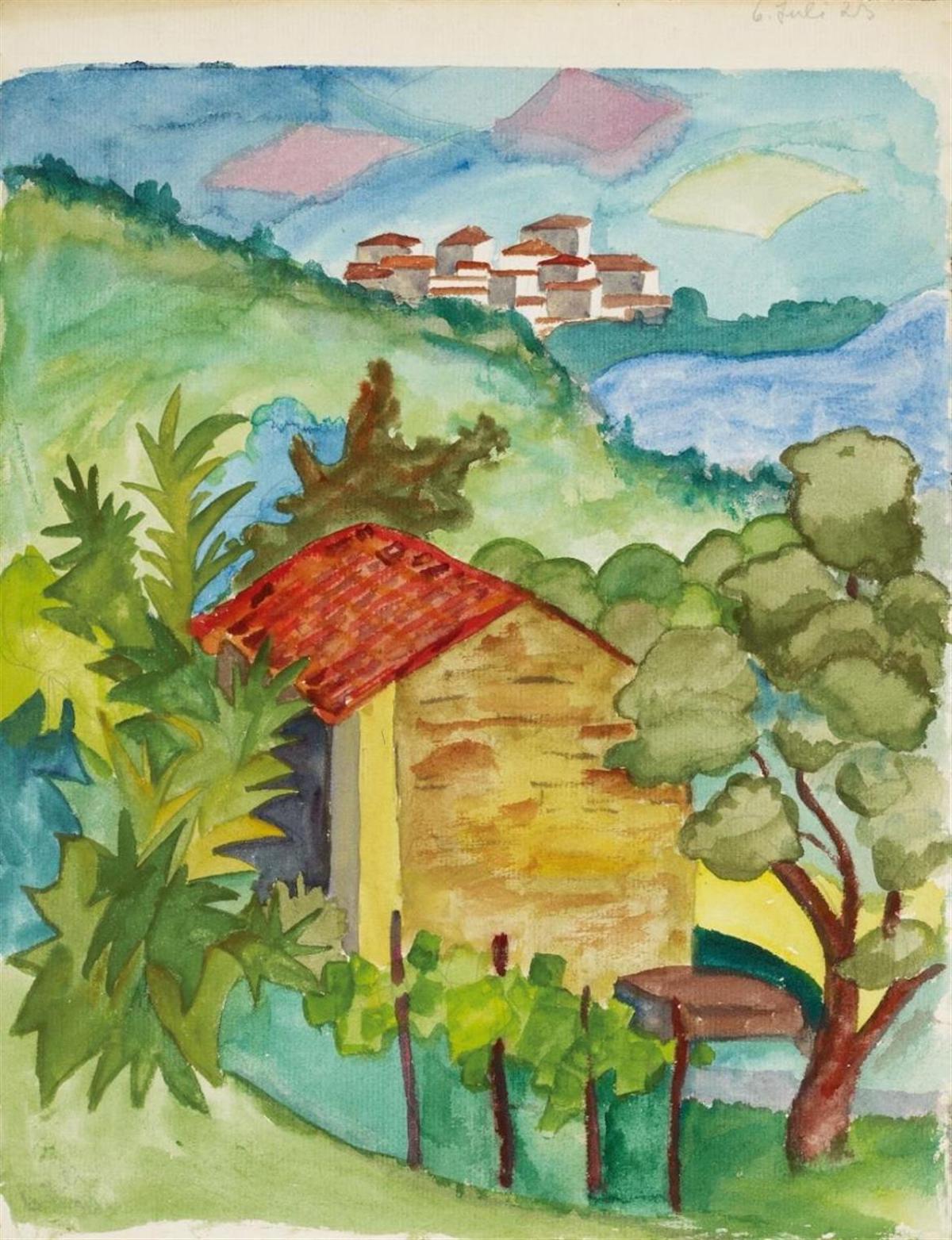

In 1920, after settling in the Ticino mountain village of Montagnola close to the Swiss-Italian border, Hesse published Wandering:

“We wanderers are very cunning – we develop those feelings which are impossible to fulfil; and the love which actually should belong to a woman, we lightly scatter among small towns and mountains, lakes and valleys, children by the side of the road, beggars on the bridge, cows in the pasture, birds and butterflies. We separate love from its object, love alone is enough for us, in the same way that, in wandering, we don’t look for a goal, we only look for the happiness of wandering, only wandering.”

Hermann Hesse – Ticino Landscape

Hesse finds sanctuary in trees, devoting an entire chapter to them:

For me, trees have always been the most penetrating preachers. I revere them when they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And even more I revere them when they stand alone. They are like lonely persons. Not like hermits who have stolen away out of some weakness, but like great, solitary men, like Beethoven and Nietzsche. In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfill themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves. Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree. When a tree is cut down and reveals its naked death-wound to the sun, one can read its whole history in the luminous, inscribed disk of its trunk: in the rings of its years, its scars, all the struggle, all the suffering, all the sickness, all the happiness and prosperity stand truly written, the narrow years and the luxurious years, the attacks withstood, the storms endured. And every young farmboy knows that the hardest and noblest wood has the narrowest rings, that high on the mountains and in continuing danger the most indestructible, the strongest, the ideal trees grow.

Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life.

A tree says: A kernel is hidden in me, a spark, a thought, I am life from eternal life. The attempt and the risk that the eternal mother took with me is unique, unique the form and veins of my skin, unique the smallest play of leaves in my branches and the smallest scar on my bark. I was made to form and reveal the eternal in my smallest special detail.

A tree says: My strength is trust. I know nothing about my fathers, I know nothing about the thousand children that every year spring out of me. I live out the secret of my seed to the very end, and I care for nothing else. I trust that God is in me. I trust that my labor is holy. Out of this trust I live.

When we are stricken and cannot bear our lives any longer, then a tree has something to say to us: Be still! Be still! Look at me! Life is not easy, life is not difficult. Those are childish thoughts. . . . Home is neither here nor there. Home is within you, or home is nowhere at all.

A longing to wander tears my heart when I hear trees rustling in the wind at evening. If one listens to them silently for a long time, this longing reveals its kernel, its meaning. It is not so much a matter of escaping from one’s suffering, though it may seem to be so. It is a longing for home, for a memory of the mother, for new metaphors for life. It leads home. Every path leads homeward, every step is birth, every step is death, every grave is mother.

So the tree rustles in the evening, when we stand uneasy before our own childish thoughts: Trees have long thoughts, long-breathing and restful, just as they have longer lives than ours. They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them. But when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy. Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is. That is home. That is happiness.

The German-born writer who later became a citizen of Switzerland was affected by the mysticism of Eastern thought. His novels, stories, and essays bear witness to the vital spiritual force that binds all life. In 1946, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature for The Glass Bead Game.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.