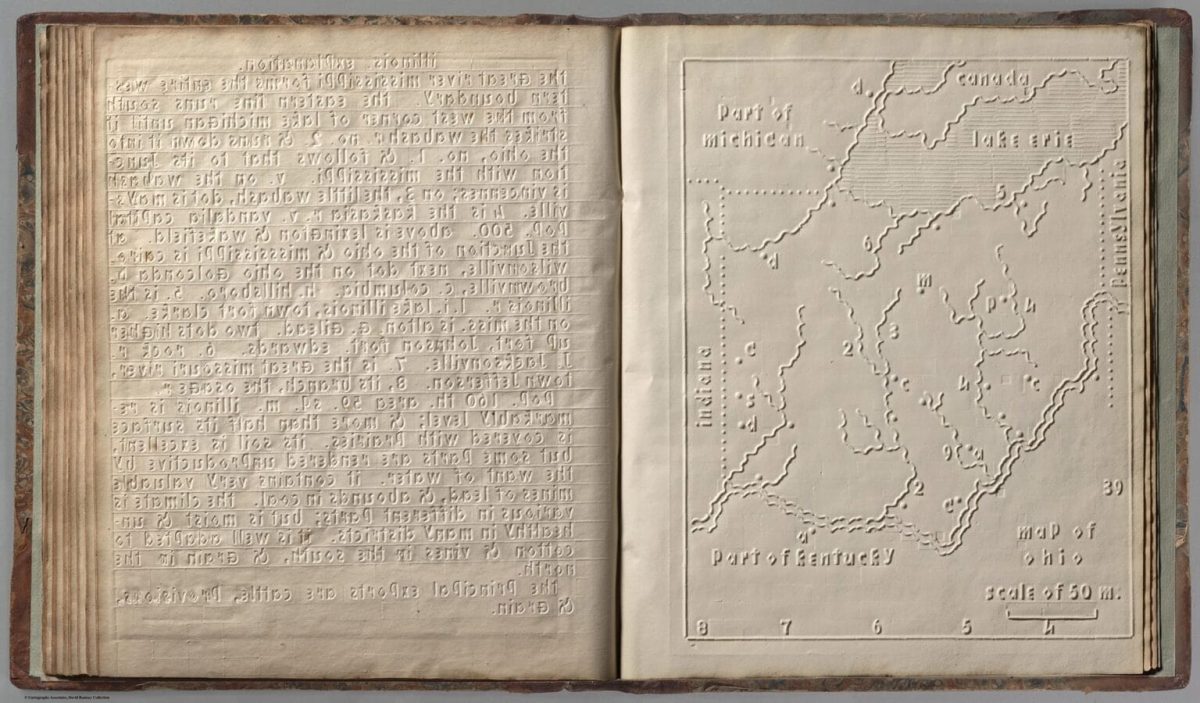

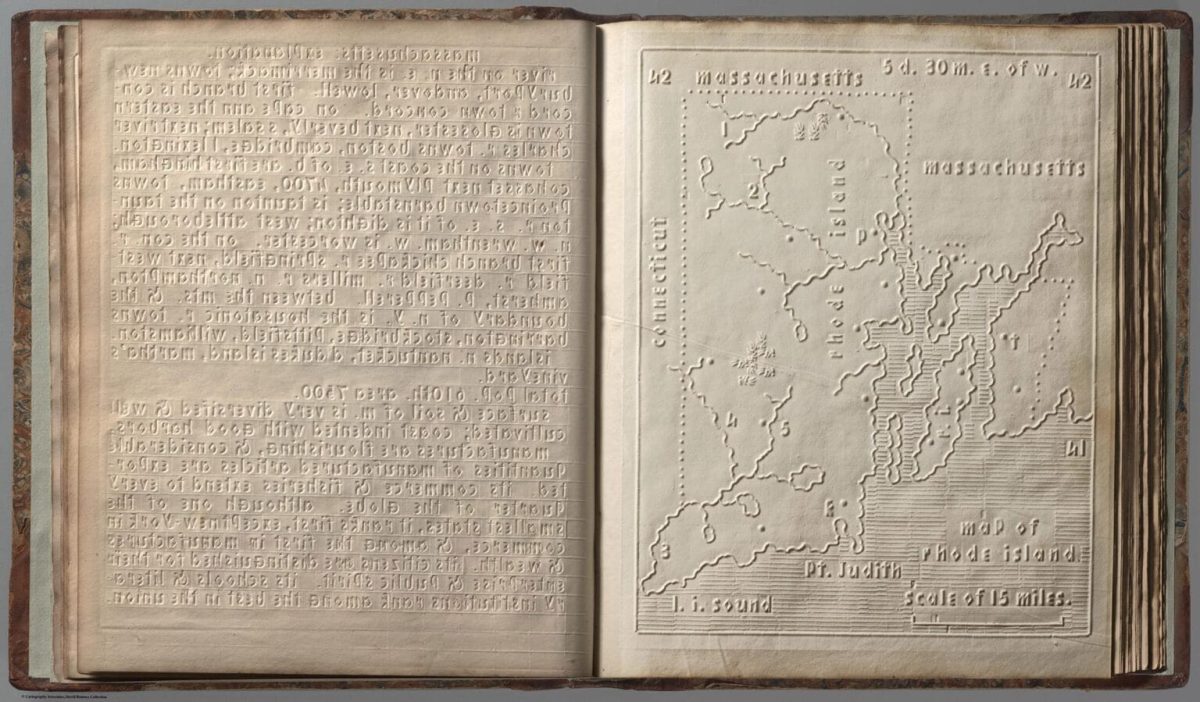

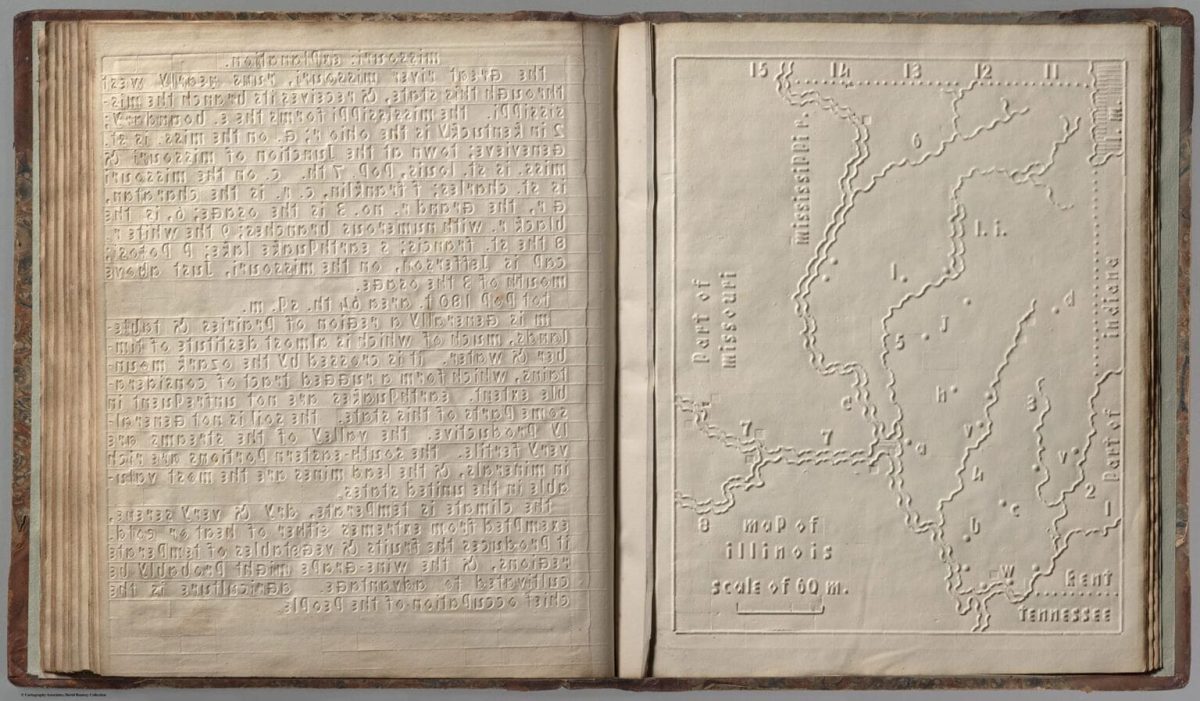

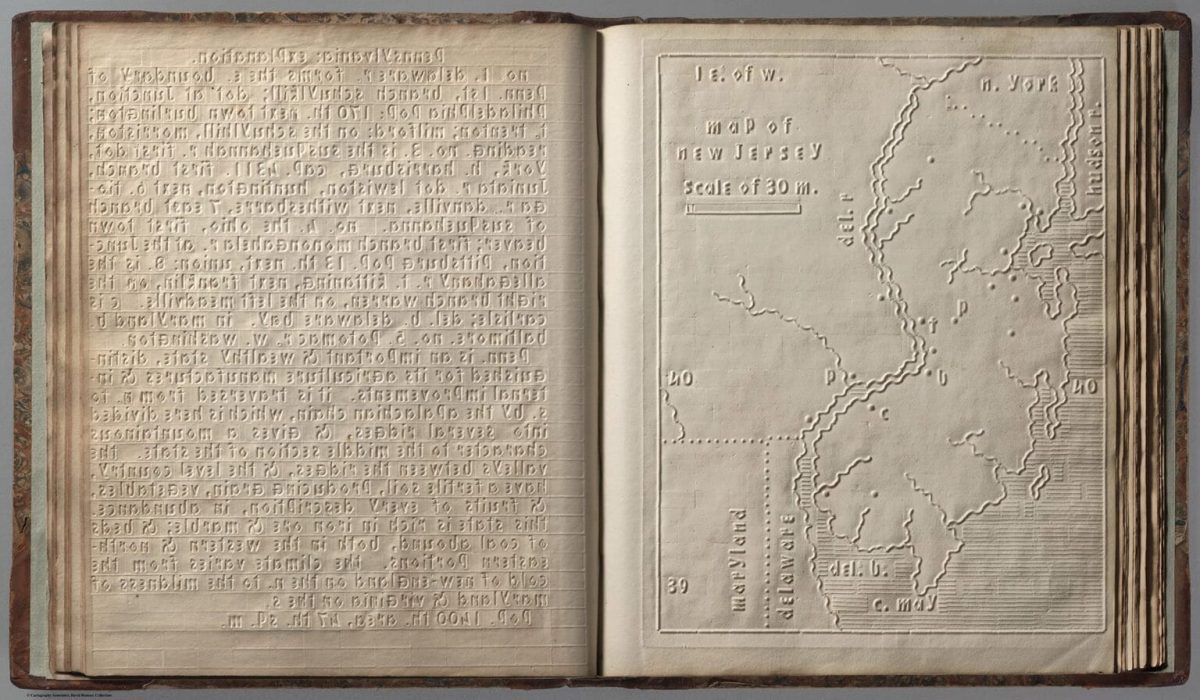

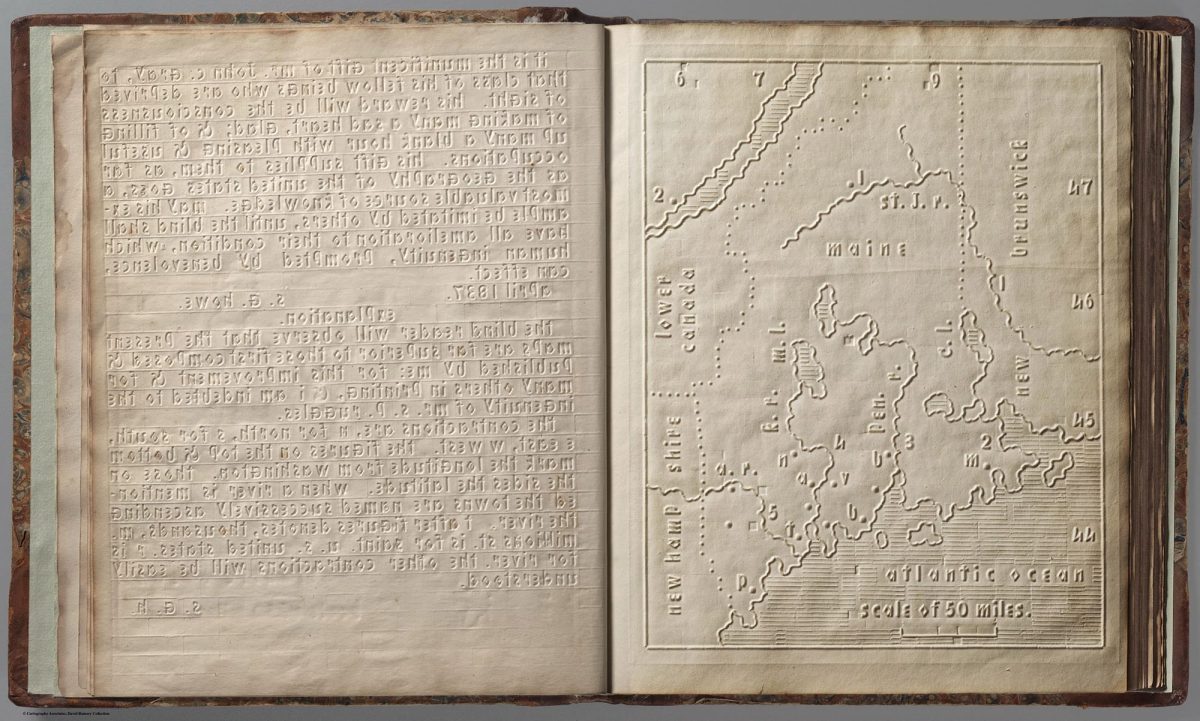

The 1837 Atlas of the United States Printed for the Use of the Blind was made to help blind children visualise geography. Supplied to children at the New England Institute for the Education of the Blind in Boston this extraordinary atlas features heavy paper embossed with letters, lines, and symbols.

It was the first atlas produced for the blind to read without the assistance of a sighted person. Braille had been invented by 1825, but was not widely used until decades later. It represented letters well, but could not represent shapes and cartographic features.

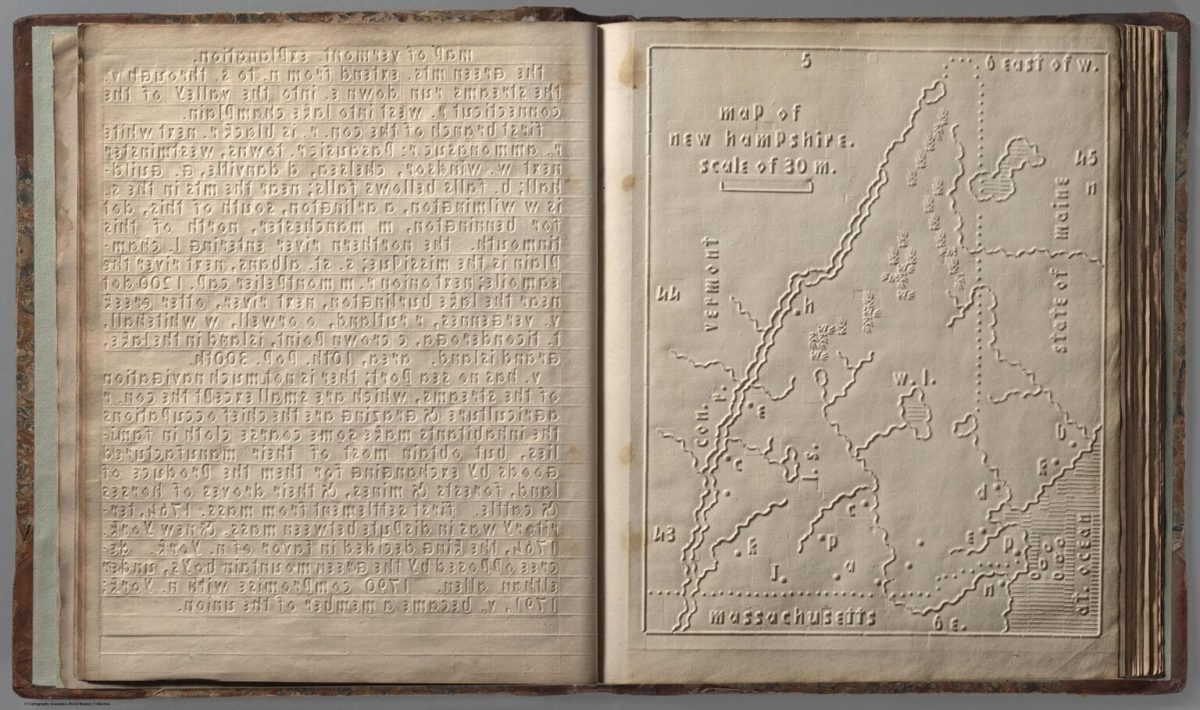

Atlas for the Blind, 1837, New Hampshire

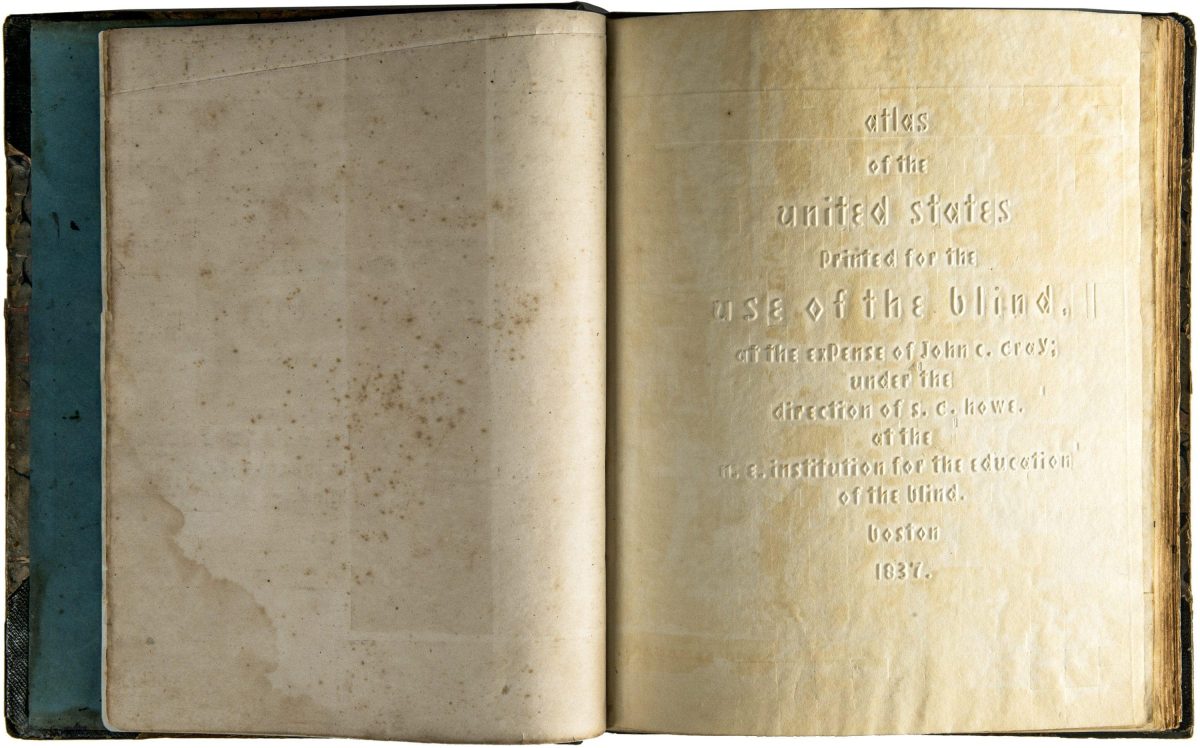

Opened in Boston in 1829, the New England Institution for the Education of the Blind was the United States’ first school for the visually impaired, dedicated to providing them with the knowledge and skills to live independently. Later known as the Perkins Institute, Samuel Gridley Howe (1801–1876) was the school’s founder and president and it was he who produced the atlas with the assistance of John C. Cray and Samuel P. Ruggles. (Howe was the husband of Julia Ward Howe, the American abolitionist and author of the US Civil War song The Battle Hymn of the Republic.)

Howe explained the methodology:

“They soon understood that sheets of stiff pasteboard, marked by certain crooked lines, represented the boundaries of countries; rough raised dots represented mountains; pin heads sticking out here and there, showed the locations of towns; or, on a smaller scale, the boundaries of their own town, the location of the meeting-house, of their own and of the neighboring houses, and the like; and they were delighted and eager to go on with tireless curiosity. And they did go on until they matured in years, and became themselves teachers, first in our school, afterwards in a private school opened by themselves in their own town.”

The Atlas was produced in-house thanks to a printing press the school acquired in 1835, which was adapted for a new style of embossed printing. This press rolled off grammar, spelling books, and more ambitious efforts such as a New Testament, Book of Psalms and a Bible. All were printed using Boston Line Type, an embossed typeface of Howe’s own design, which remained in use for decades until replaced by Braille. Boston Line Type features the Roman alphabet pressed into the page so that it was raised and tactile. The letters are all lowercase.

And it was successful. Harriet Gamage, who was an early Perkins student, praised the wrote to Howe: “As I am in a great measure indebted to your noble institution for the faculties I may enjoy I will name the branches I am at present imparting. Reading, Spelling, Arithmetic, History, Geography, the maps, such as the seeing use, which I am enabled to explain from a retentive memory, and a reference to my own which are so beautifully embossed.”

Each type of information is represented by a different tactile symbol: dotted lines for state boundaries; solid raised lines for rivers and “ribbed” lines to distinguish bodies of water from solid land; and letters and numbers for places and landmarks, explained by accompanying descriptive text.

Via: Cartographic Perspectives,

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.