“I shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man.”

– John Calhoun, Universe 25

The Universe 25 experiment, carried out by American scientist John Calhoun between 1968 and 1972, produced an unexpected result. A once thriving community of 2,200 of mice had collapsed. Just over 100 remained alive, and soon they would all be dead. The mice would become extinct.

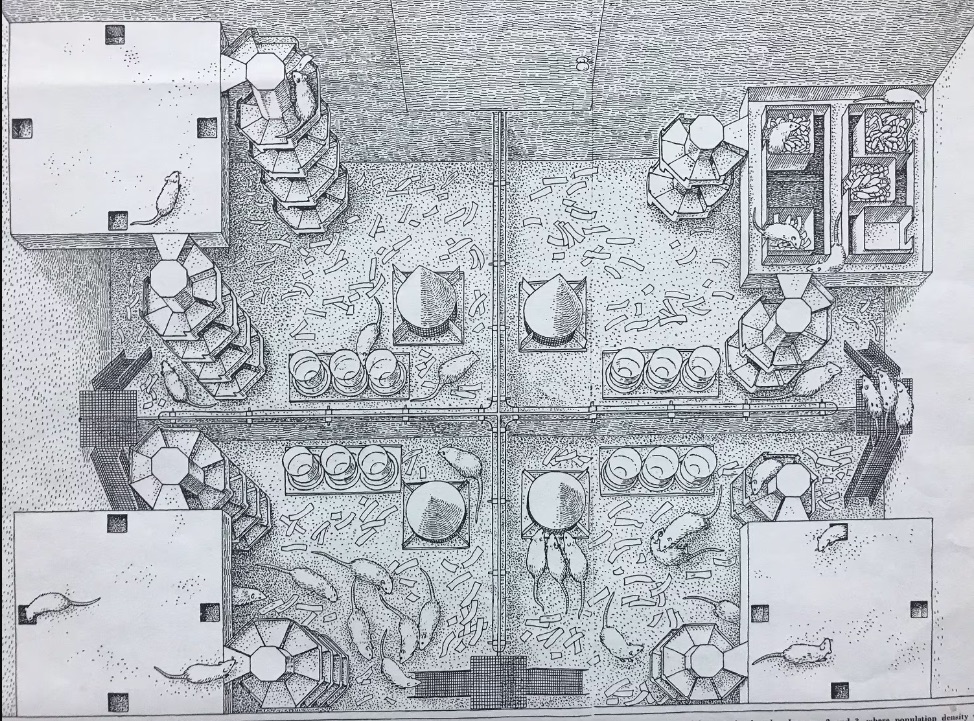

The mice were living in Calhoun’s ‘Mouse Paradise’ (aka: Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice), an ideal environment, with unlimited food and water, tons of nesting material and plenty of space. He would use this world to study how society reacts to a growing population.

Universe 25: From Calhoun’s papers at the National Library of Medicine: a graphic of a “rat utopia” or “mouse paradise.”

He chose balb-C albino, a common lab mouse, bred by the NIH Animal Center and more or less guaranteed disease-free and behaviourally normal. Calhoun marked each mouse with a unique colour combination.

They lived in 16 identical apartment buildings arranged in a square with four buildings on every side, each with four four-unit walk-up one-room apartments, for a total of 256 units, each of which could comfortably house about 15 mice. There were also a series of dining halls in each apartment building and a cluster of rooftop fountains.

For over three years, Calhoun and his team sat in a loft above this world and watched.

Universe 25

Calhoun had previously experimented with rats on farmland at Rockville, Maryland, starting in 1947. While working at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 1954, he made more experiments with rats and mice but had been restricted by (irony of ironies) lack of space. But Universe 25, so named because it was his 25th experiment of its kind, was the first time his experiment had run its full course.

Beginning with four mating pairs, the mice thrived. But after 317 days, the population stopped growing and began to stagnate. When there were 600 mice, Calhoun observed that they’d formed hierarchies. The strongest mice began to attack others, and aggressive and maladaptive behaviours emerged, such as violence between females and a lack of reproductive interest in males.

Male counterparts to these non-reproducing females we soon dubbed the ‘beautiful ones’. They never engaged in sexual approaches toward females, and they never engaged in fighting, and so they had no wound or scar tissue. Thus their pelage remained in excellent condition. Their behavioural repertoire became largely confined to eating, drinking, sleeping and grooming, none of which carried any social implications.

Adding:

They never learned to be aggressive, which is necessary in defense of home sites. They never learned to court, so there was no mating. Being no mating, there were no progeny.

As passive, non-reproductive males dominated, the birth rate plummeted, juvenile mortality rocketed, and the colony collapsed into cannibalism, incest and homosexuality.

Calhoun called his discovery ‘behavioural sink’ in a February 1, 1962, Scientific American article titled “Population Density and Social Pathology”.

Behavioral Sink

Calhoun enlarged on what he described as ‘behavioral sink’:

“Many [female rats] were unable to carry the pregnancy to full term or to survive delivery of their litters if they did. An even greater number, after successfully giving birth, fell short in their maternal functions. Among the males the behavior disturbances ranged from sexual deviation to cannibalism and from frenetic overactivity to a pathological withdrawal from which individuals would emerge to eat, drink and move about only when other members of the community were asleep. The social organization of the animals showed equal disruption.

“The common source of these disturbances became most dramatically apparent in the populations of our first series of three experiments, in which we observed the development of what we called a behavioral sink. The animals would crowd together in greatest number in one of the four interconnecting pens in which the colony was maintained. As many as 60 of the 80 rats in each experimental population would assemble in one pen during periods of feeding. Individual rats would rarely eat except in the company of other rats. As a result extreme population densities developed in the pen adopted for eating, leaving the others with sparse populations.

“In the experiments in which the behavioral sink developed, infant mortality ran as high as 96 percent among the most disoriented groups in the population.”

As For Mice and Rats, So Too For Humans

The experiment was a national talking point. As early as 1968, journalist Tom Wolfe titled an essay about New York O Rotten Gotham—Sliding Down into the Behavioral Sink. “It would not be long before a “population collapse” or a “massive die off”, he told his readers.

In Time magazine’s 1971 article, Population Explosion: Is Man Really Doomed? writer Otto Friedrich noted that “even if some way can be found to feed the onrushing millions [of humans], they may still face a psychic fate similar to the one that befell Dr John Calhoun’s white mice”.

Biologist Paul Ehrlich had recently written about the end of all life in the bestselling The Population Bomb (1968) – “Population Control or Race to Oblivion?” Also in ’68, philosopher Garrett Hardin had promoted the “tragedy of the commons”, a demand for regulated access to public goods that led to his “lifeboat ethics” (1974). American architect Buckmeister Fuller wanted us to think of “Spaceship Earth”, a finite, life-preserving container.

And at the cinema, the 1973 film Soylent Green, based on Harry Harrison’s 1966 sci-fi novel Make Room! Make Room!, told the story of New Yorkers dependent on food handouts which, it emerges, are derived from human corpses.

The apocalypse was nigh.

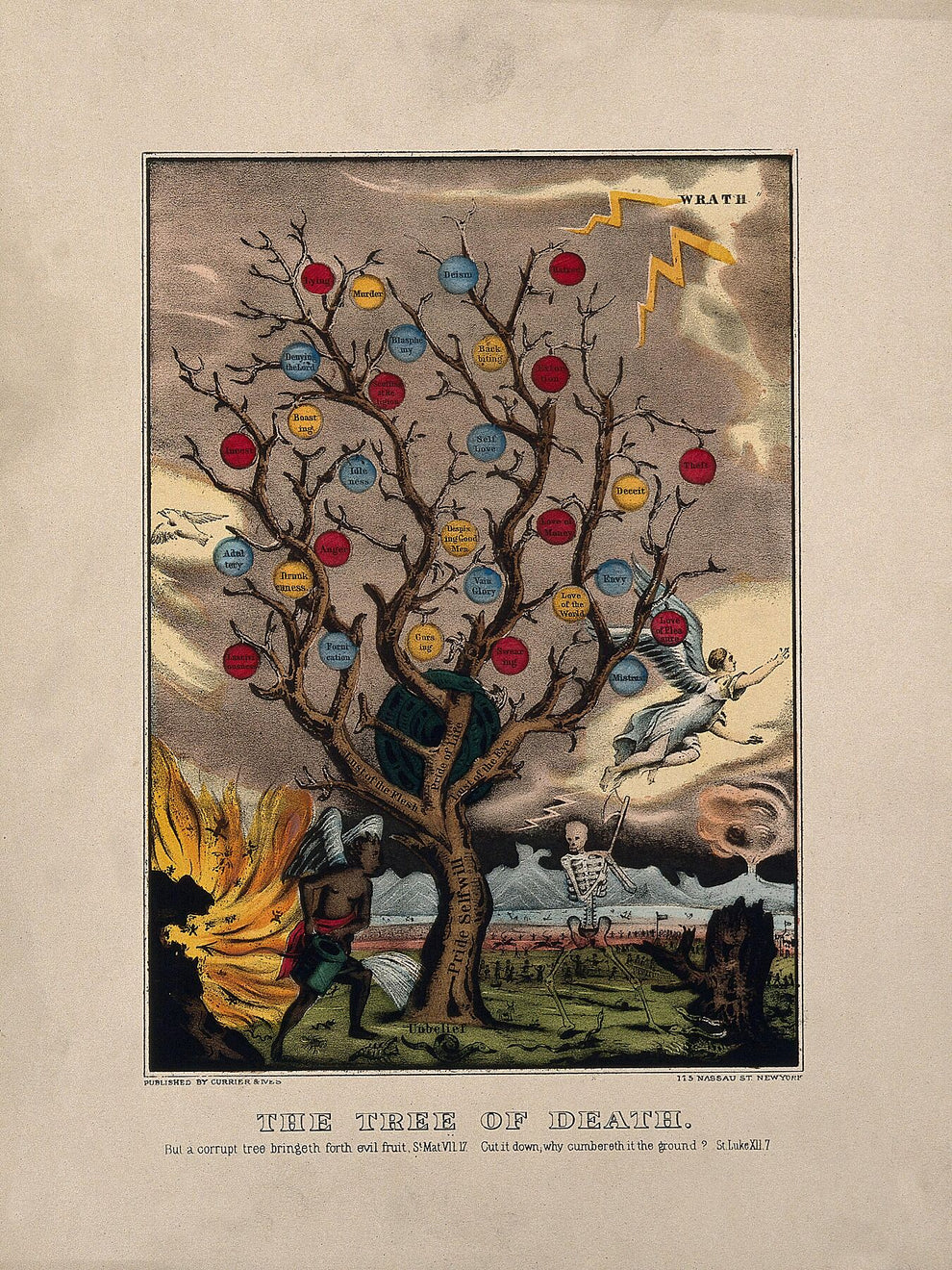

Devouring The Tree of Life

And there was Calhoun, who had called his early enclosures “rat cities” and had sought to recreate the vertical organisation and pressure-points (stairwells, corridors) that were characteristic of much of the post-war mass-housing projects that had sprung up across the US.

And there was also God and the Christian Bible. Calhoun was a religious man. In his paper Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population and destiny, published by the Section on Behavioral Systems at the Laboratory of Brain Evolution & Behavior, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland, we read Calhoun’s address to the Royal Society of Medicine in London on 22 June 1972. He did not beat about the bush as he addressed his peers. (You can read the entire text below).

“I shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution. Threatening life and evolution are the two deaths, death of the spirit and death of the body. Evolution, in terms of ancient wisdom, is the acquisition of access to the tree of life. This takes us back to the white first horse of the Apocalypse which with its rider set out to conquer the forces that threaten the spirit with death. Further in Revelation (ii.7) we note: ‘To him who conquers I will grant to eat the tree’ of life, which is in the paradise of God’ and further on (Rev. xxii.2): ‘The leaves of the tree were for the healing of nations.'”

1984 and All That

In the Q and A that followed Calhoun’s address, the matter of 1984 was raise, the date having resonance for anyone familiar with English writer George Orwell’s dystopian novel of that name:

Professor Mellanby: Dr Calhoun had suggested that by 1984 man was going to be as crowded as his mice and that this would have disastrous effects.

Calhoun: …1984 was not the year in which ultimate density would be attained, but a date beyond which the opportunity for decision making and designing to avoid population catastrophe might be quickly lost.

So rats are humans?

“Of course, we realise that rats are not men,” Calhoun said, “but they do have remarkable similarities in physiology and social relations. We can at least hope to develop ideas that will provide a spring forward for attaining insights into human social relations and the consequent state of mental health.”

The Council of The Rats by Gustave Doré – 1868 – print.

Don’t panic!

In 2018, Jon Adams, of the London School of Economics, and Edmund Ramsden, of the University of London, looked closer at pessimistic visions for humanity in an discusison at the National Library of Medicine. It wasn’t about food and water. Living well is about space:

In Calhoun’s rodent pens, we’re reminded of the dual nature of the walls we build, and of their foundational importance to the very idea of civilization, as the guarantors of both our privacy and our loneliness. Those queer prizes we collectively desire, and the vital importance of architecture to their achievement.

Ramsden noted that Calhoun didn’t necessarily think humanity was doomed.

In some of Calhoun’s other crowding experiments, rodents developed innovative tunneling behaviors, while in others, adding more rooms allowed the animals to live in the high-density environment without being forced into unwanted contact with others, largely minimizing the negative social consequences. According to Ramsden, Calhoun wanted these findings to influence the architectural design of prisons, mental hospitals, and other buildings prone to crowding. Writing in a report summary in 1979, Calhoun noted that “no single area of intellectual effort can exert a greater influence on human welfare than that contributing to better design of the built environment.”

In The Chronicle of Higher Education, we spot an interesting footnote on Calhoun’s work:

In perhaps the oddest twist of all, as early as the 1960s, Calhoun’s studies of mice and rats led him to devote a good deal of the later years of his career to working on the creation of a human “world brain”. “We are now at the critical transition to a new type of man,” Calhoun told an audience in 1969, “one which depends increasingly on extracortical prostheses to evolve and utilise concepts.”

Calhoun was convinced that by linking together these extracortical prostheses – akin to today’s internet hubs – we might be able to harness creativity and, among other things, figure a way out of the overpopulation problem. Never one to shy away from bold prediction, Calhoun told this same audience that “a rough calculation indicates that by 40,000 years from now less than 5% of creative activity will be done by our cortex and at least 95% by prostheses”.

When Calhoun died of a heart attack and stroke he suffered while on holiday in 1995, the New York Times and Washington Post ran obituaries. Both described the behavioural sink, as well as rodent universes full of Beautiful Ones.

- You can read the full text of Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population by John B Calhoun at this link: Death Square – Universe 25

Via: The Scientist,

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.