“I have never described any thing without first having seen it with my eyes”

– Ulissi Aldrovandi, who shows us dragons and other monsters in his Monstrorum Historia

Ulissi Aldrovandi’s Monstrorum Historia is a huge 13-volume encyclopaedia of life on Earth. The books cover different subjects: quadrupeds, fish, sea life, birds, serpents, plants and minerals. Published between 1599 and 1648, most of books run to at least 700 pages.

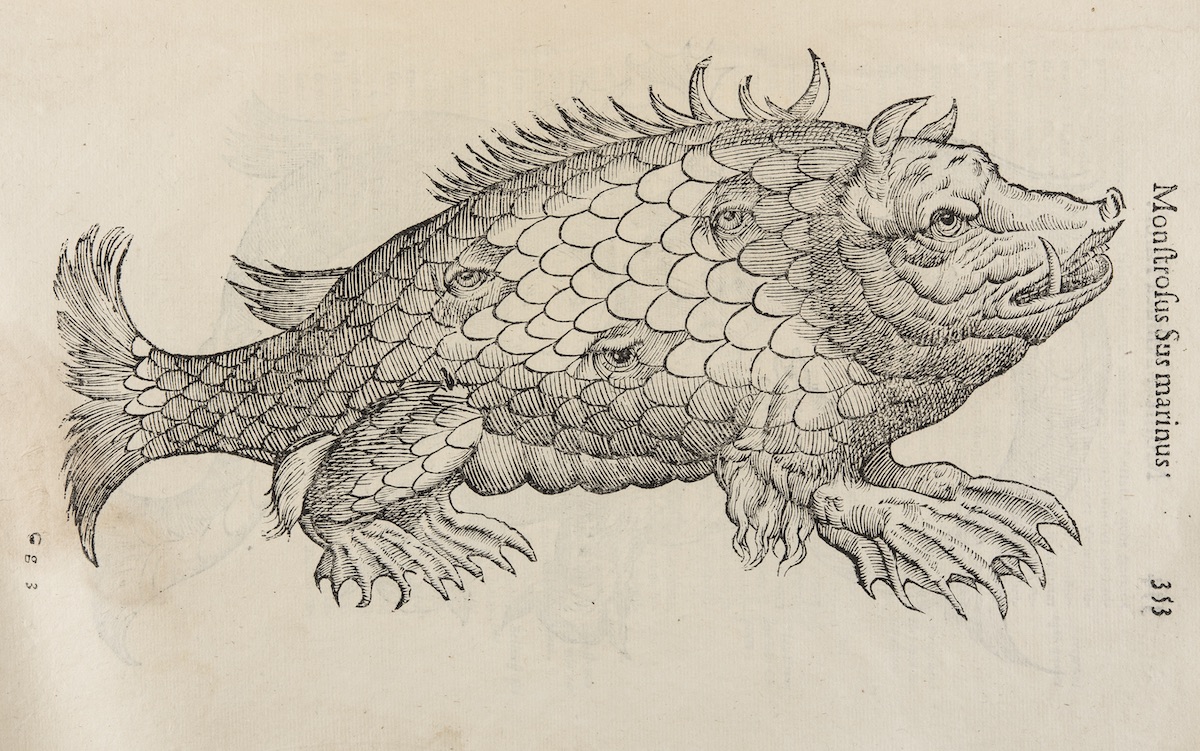

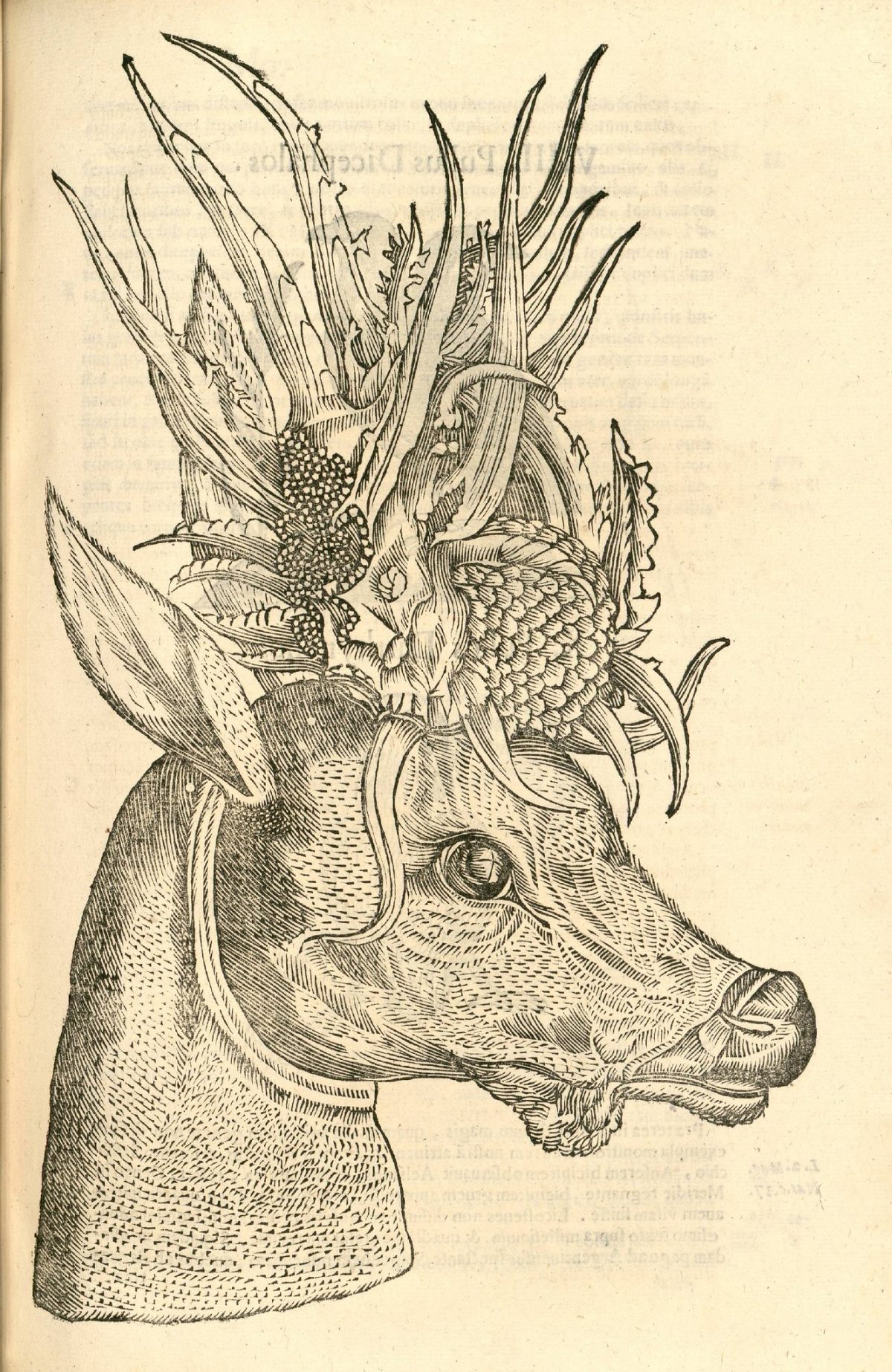

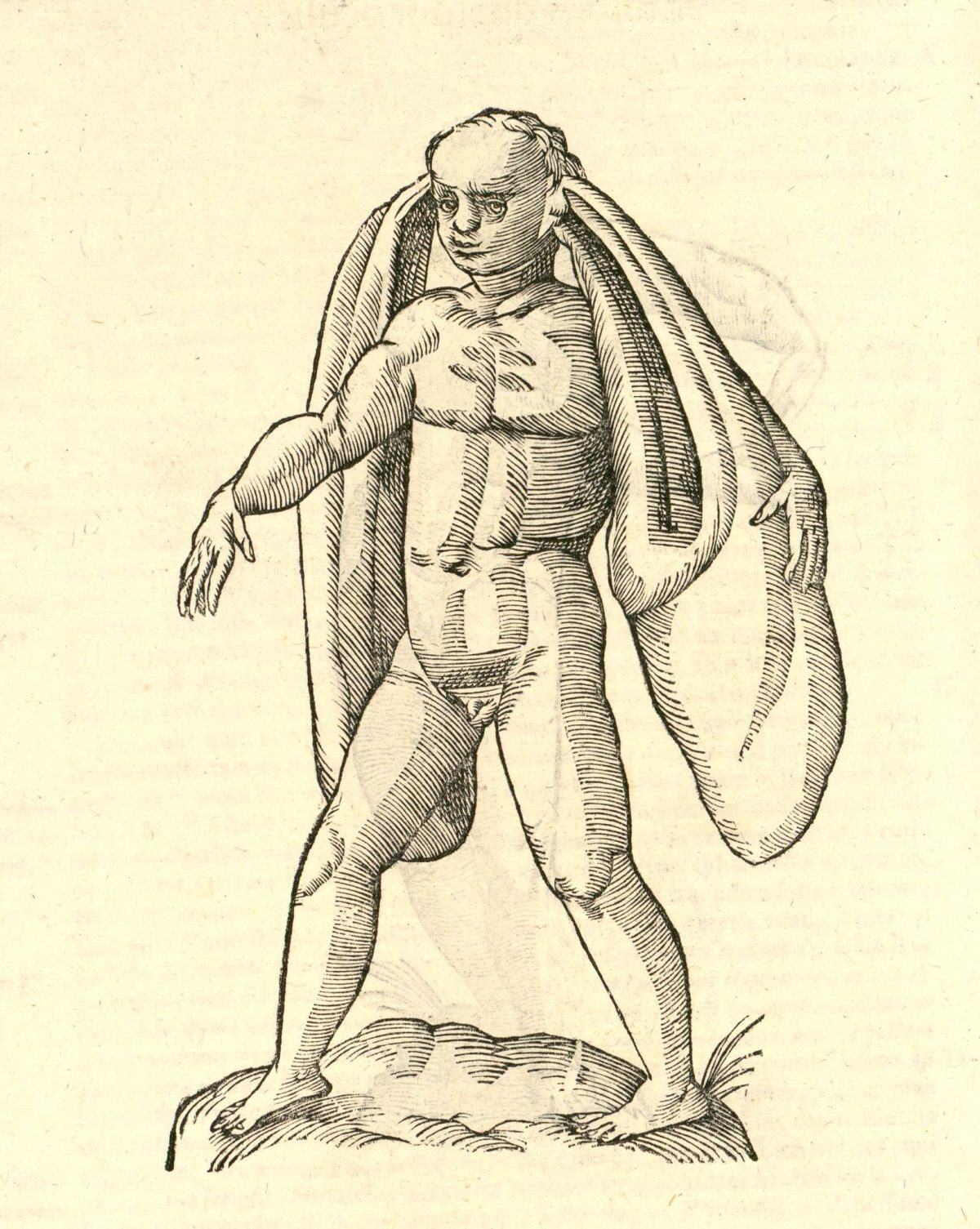

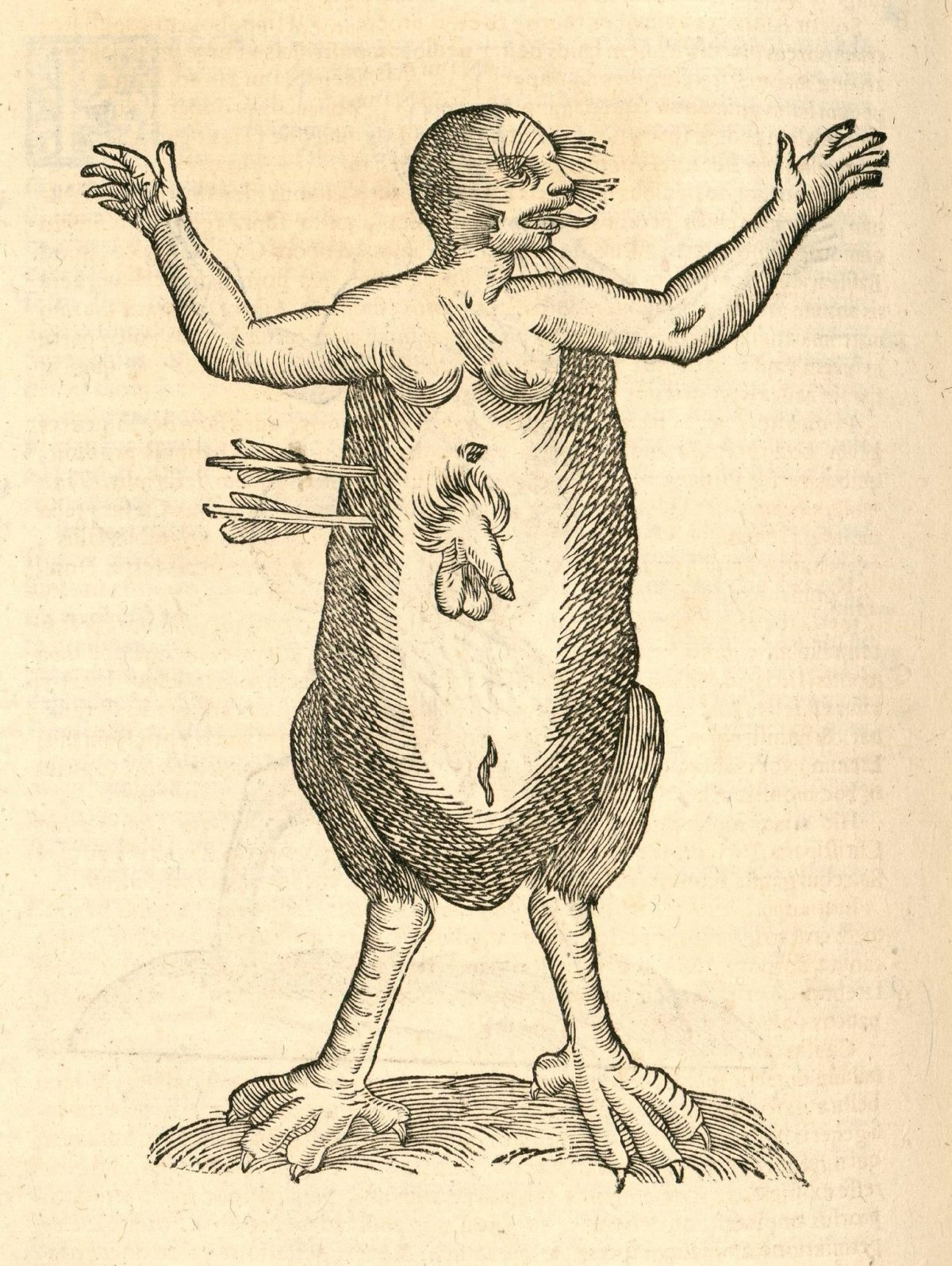

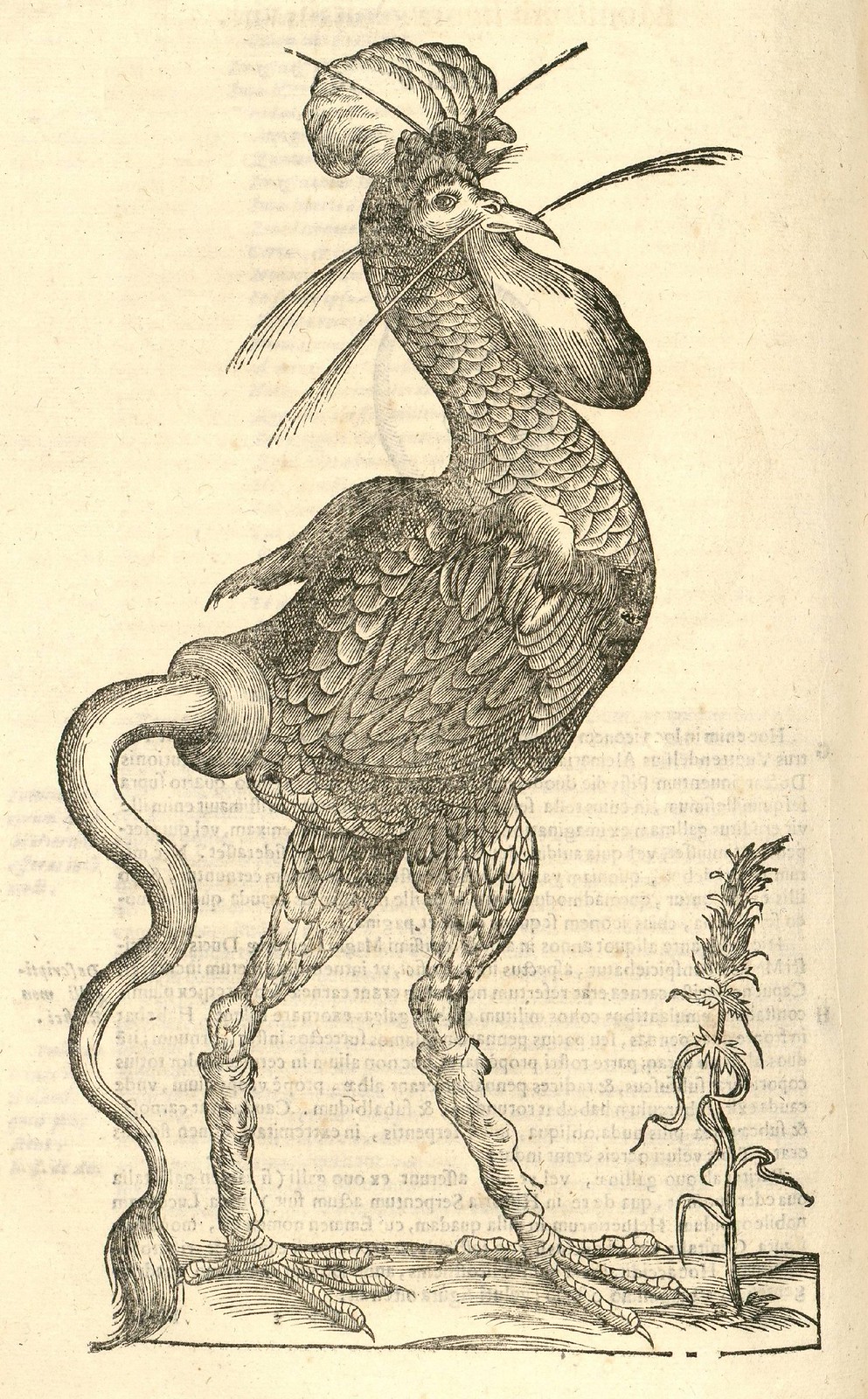

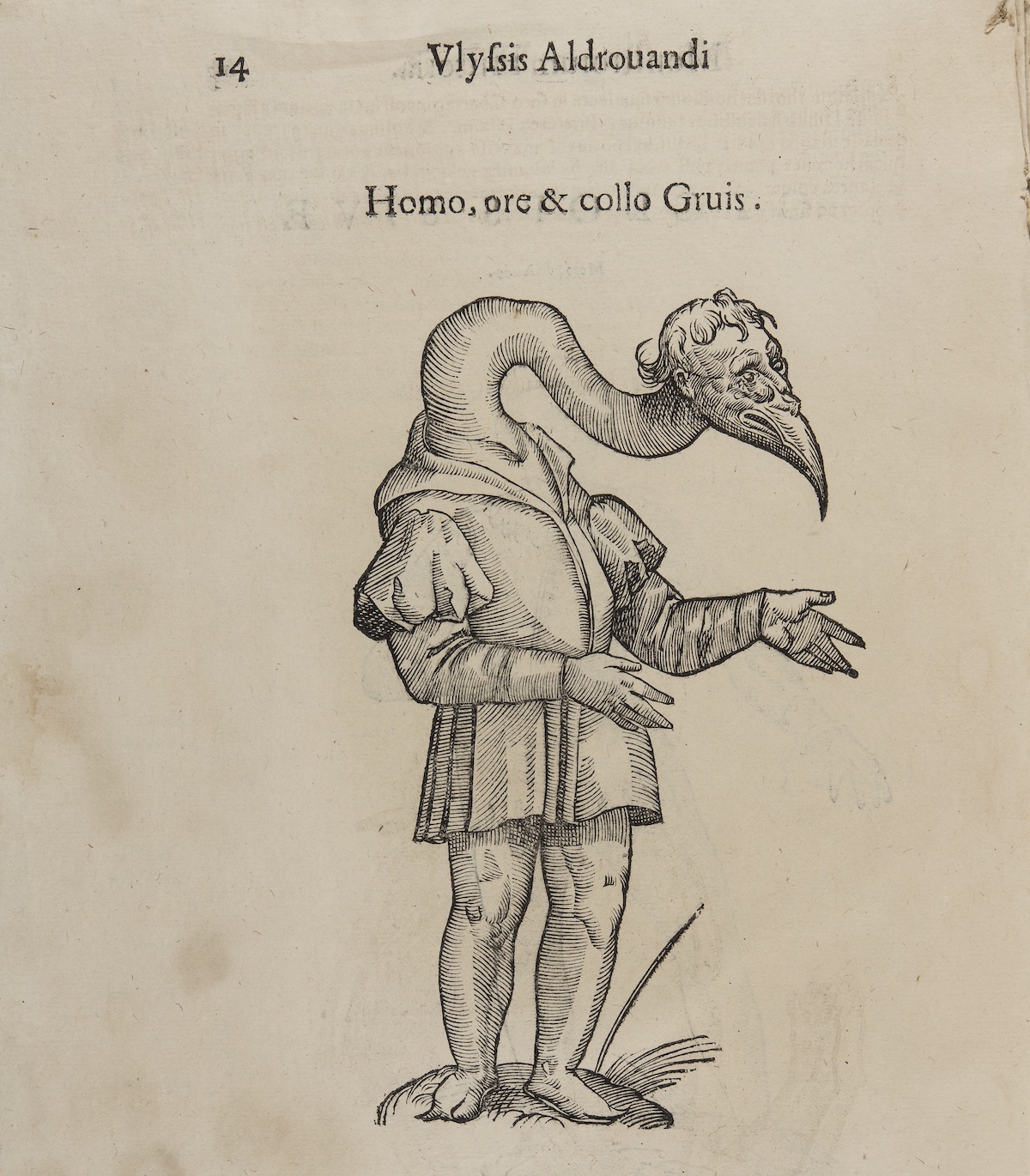

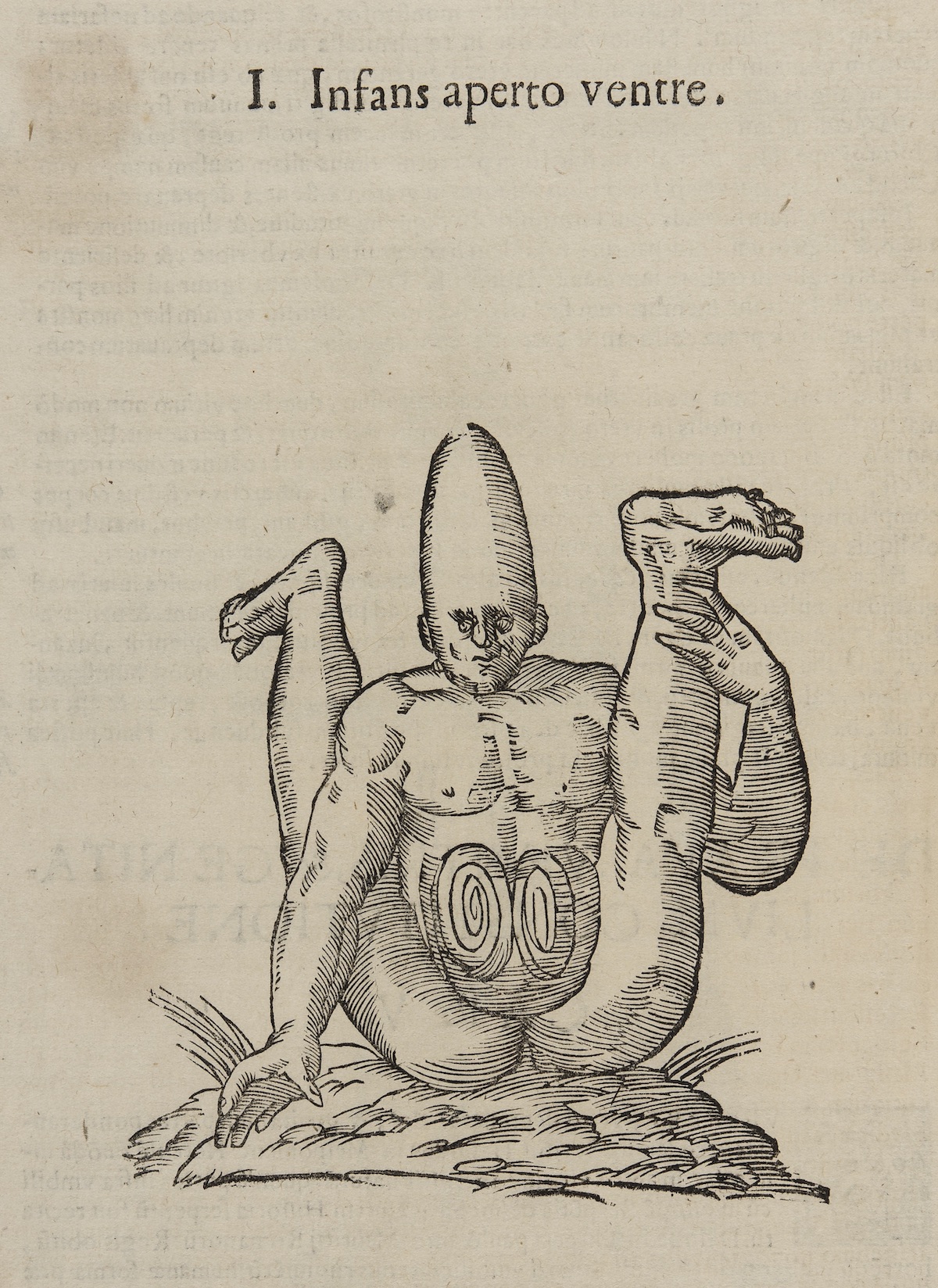

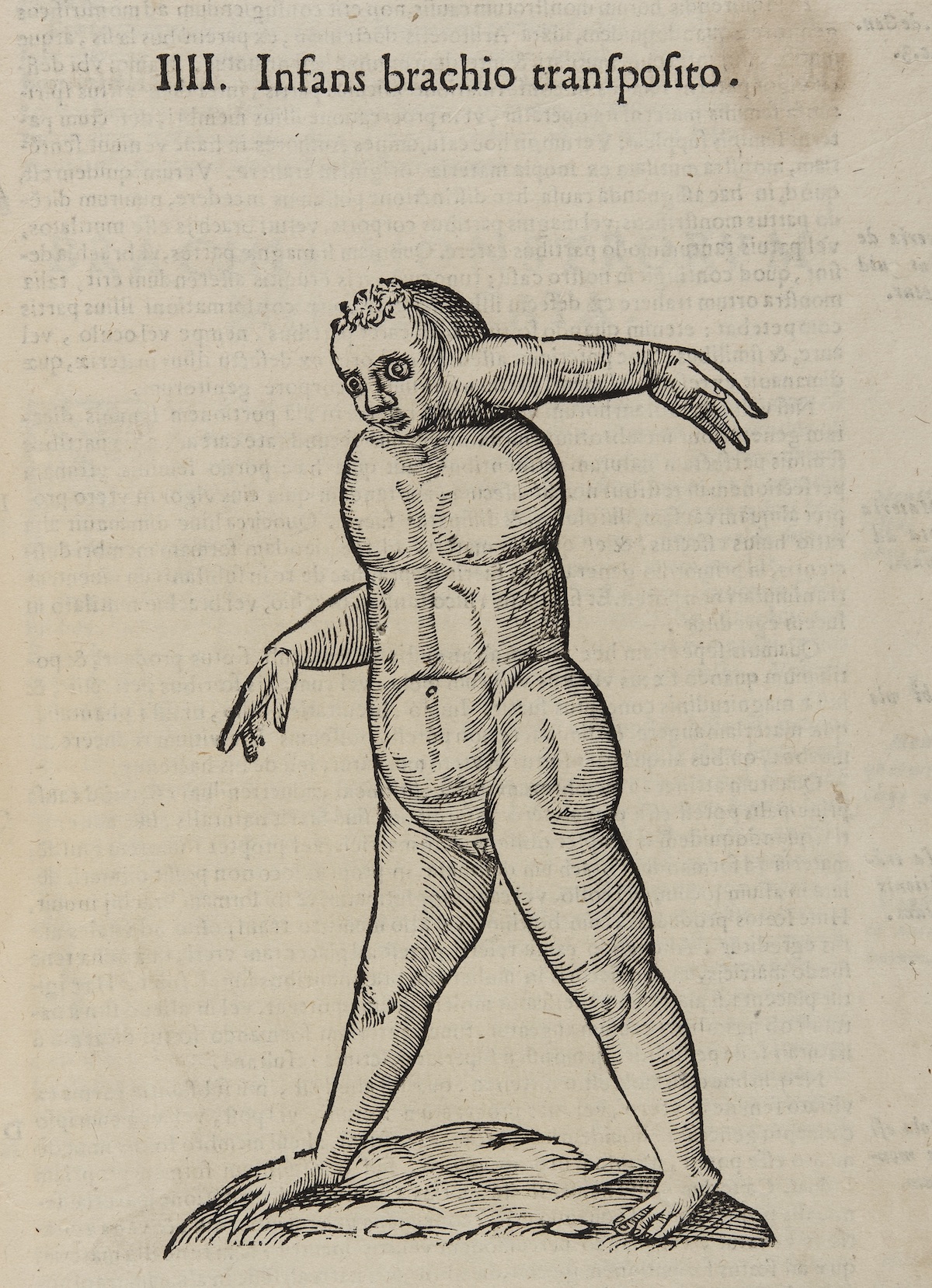

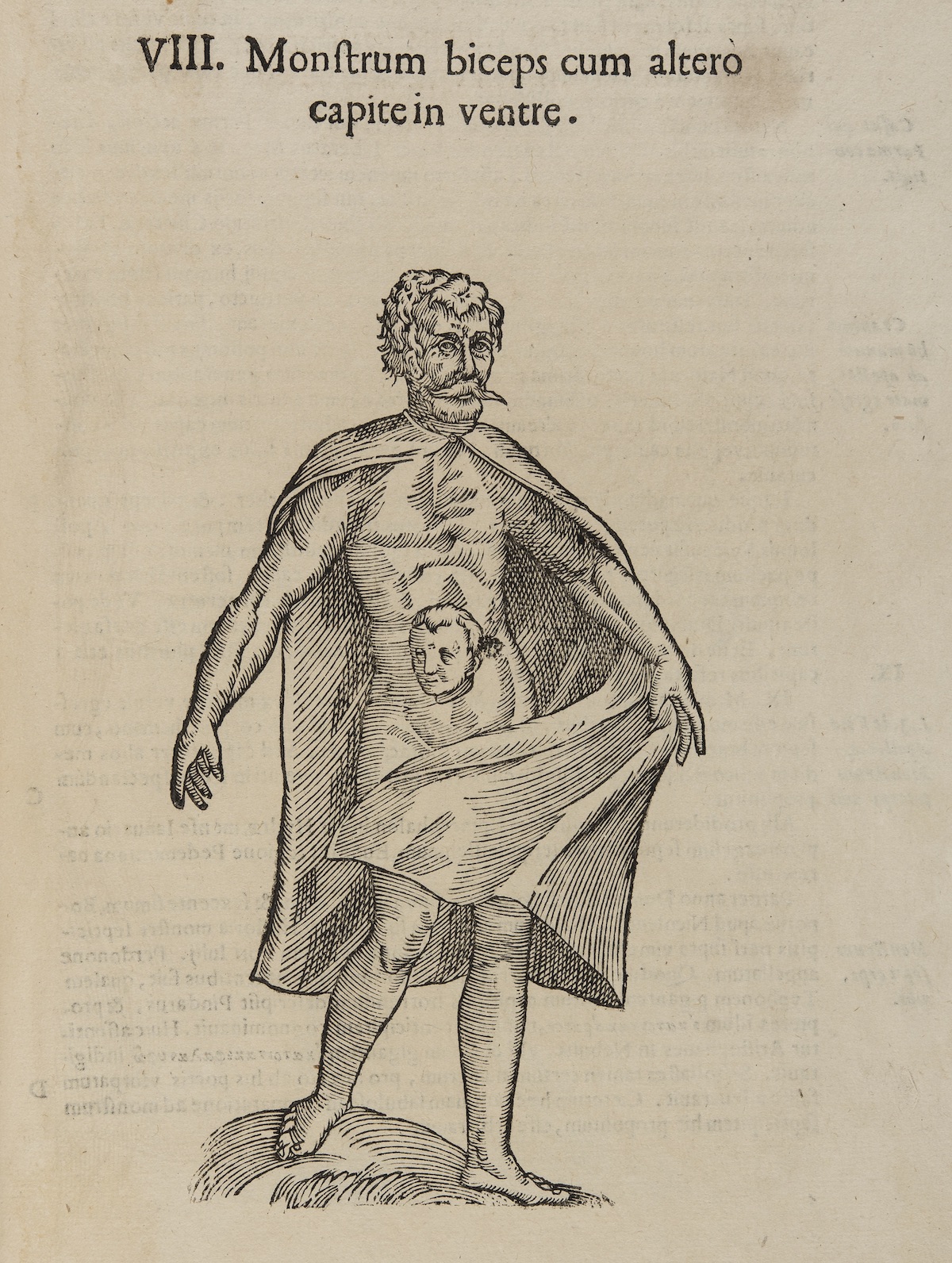

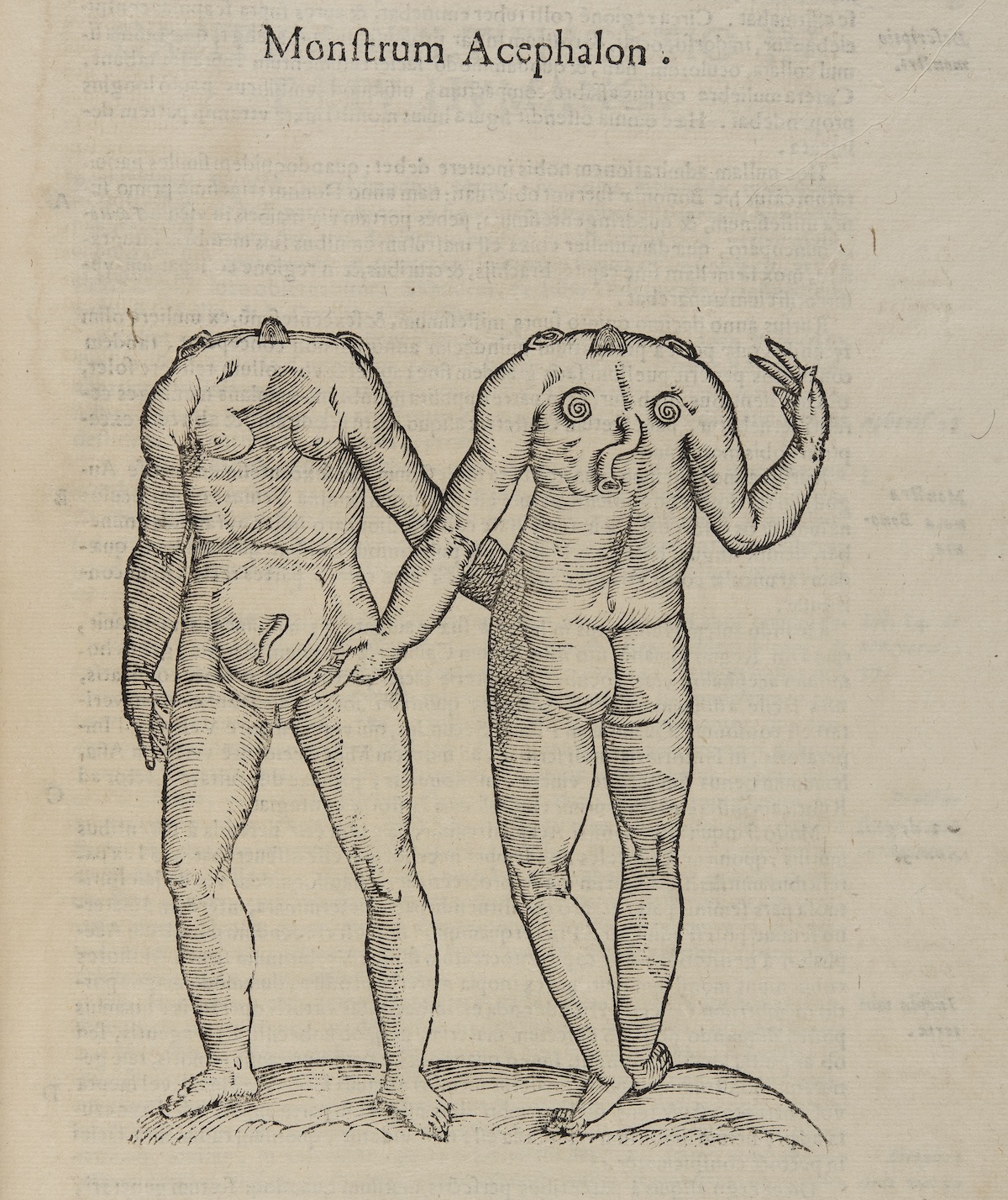

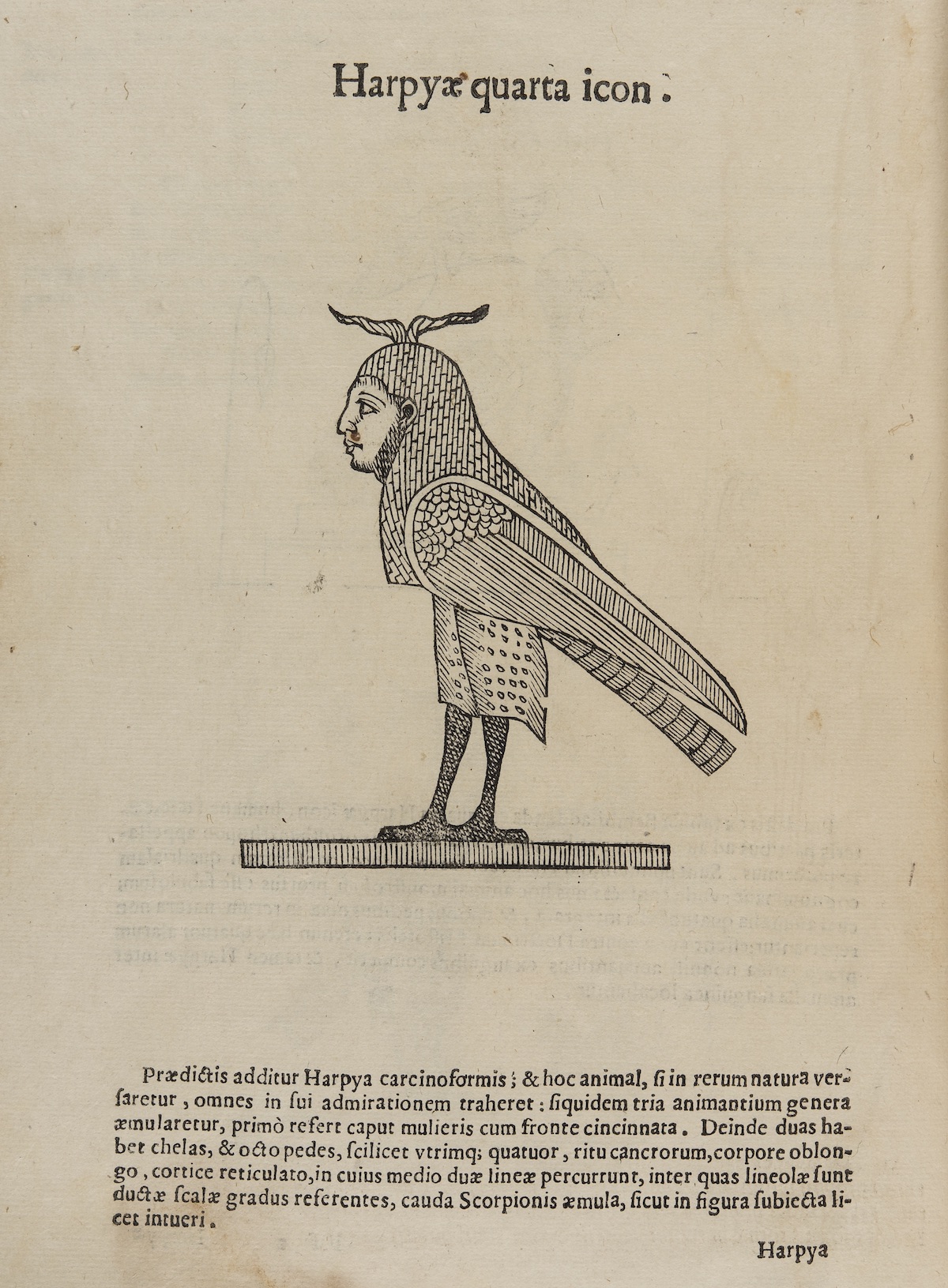

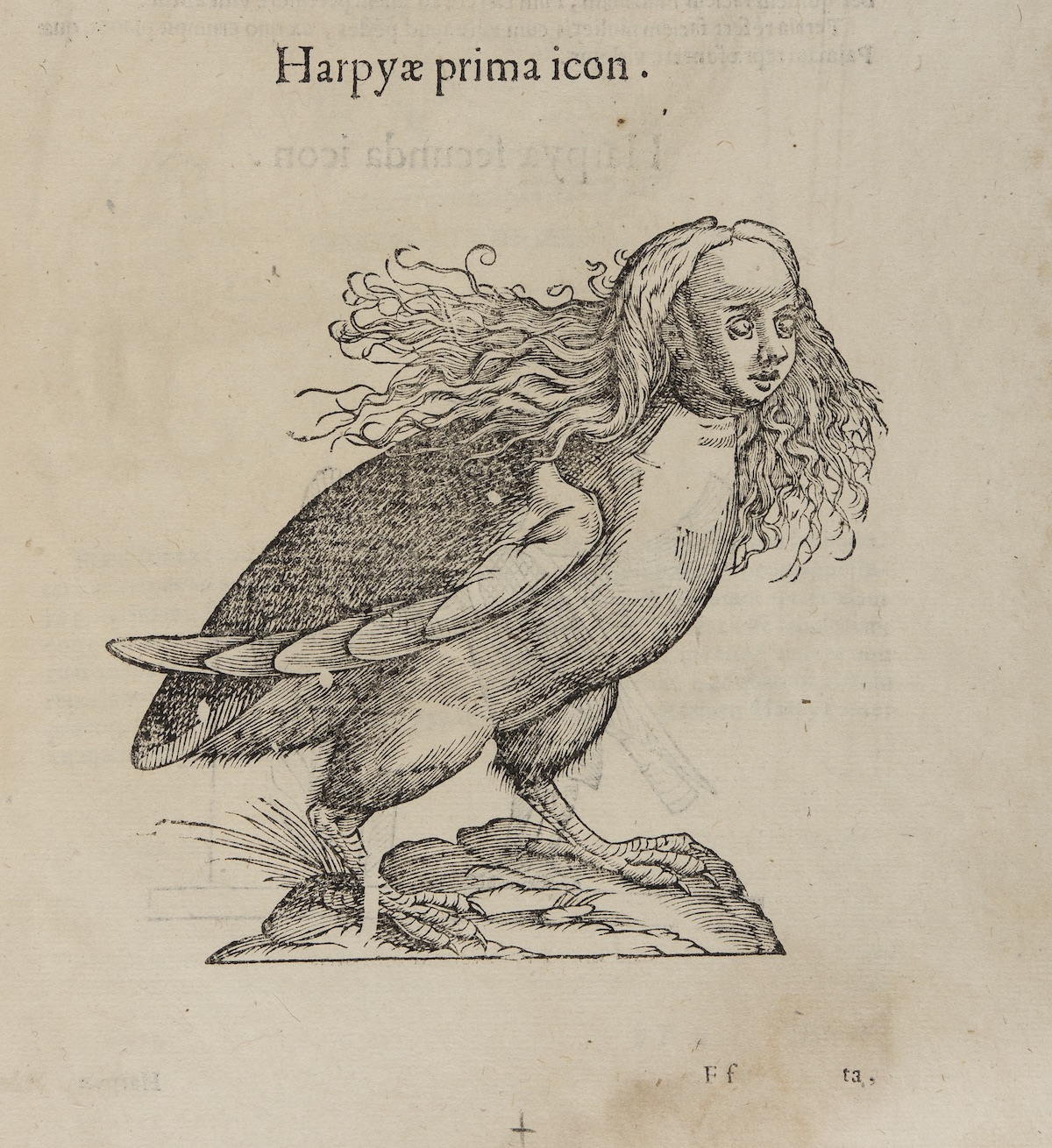

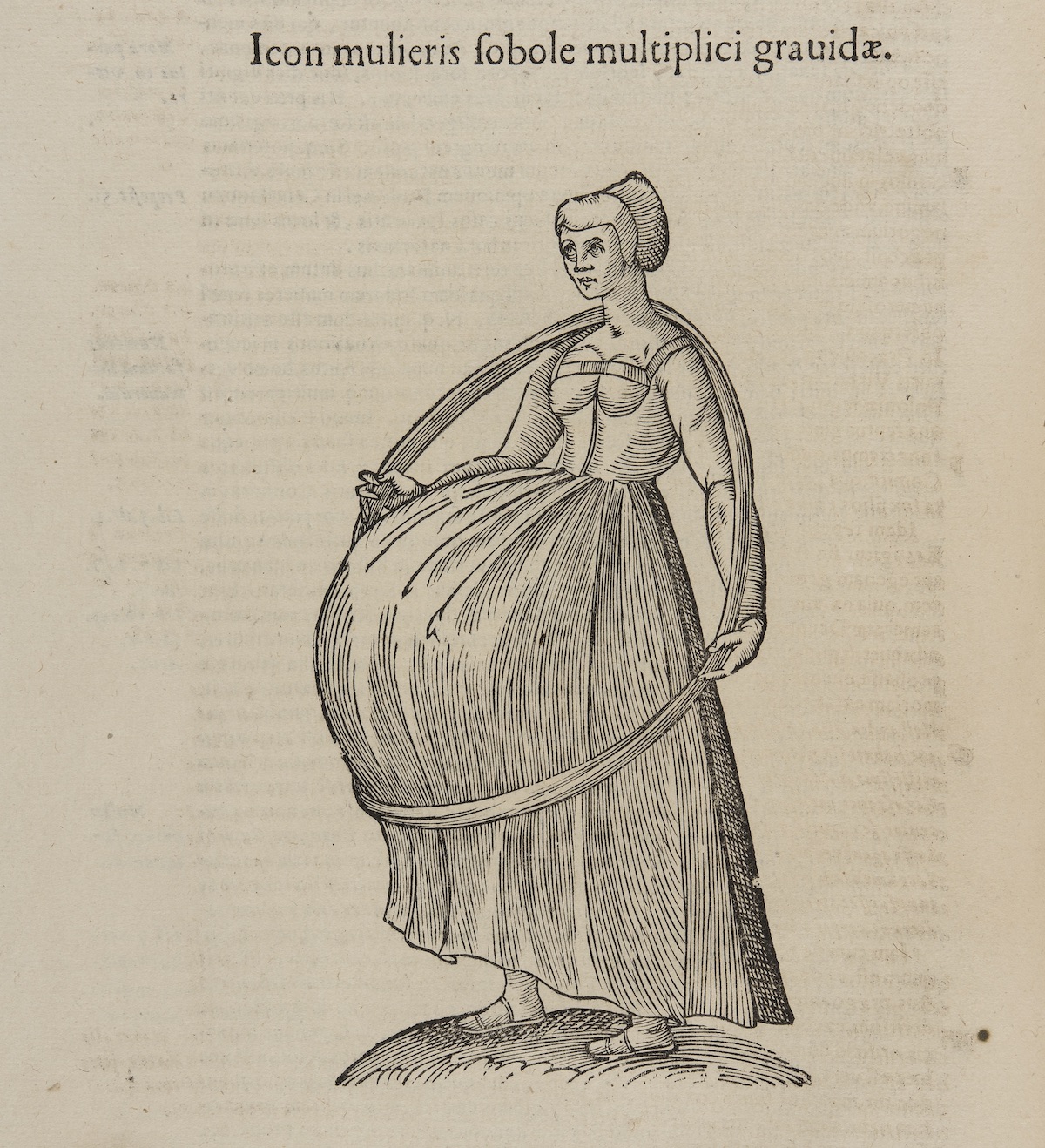

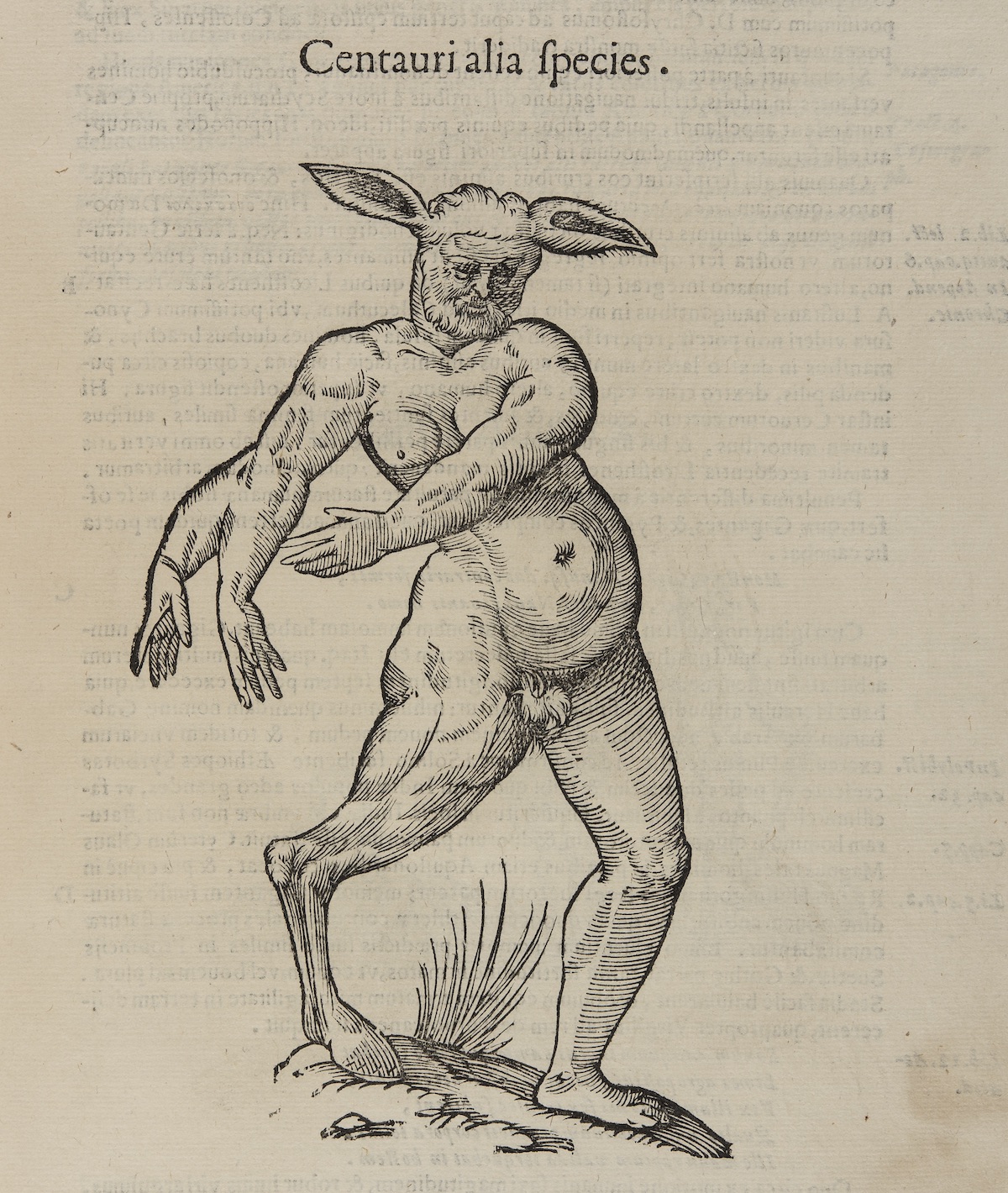

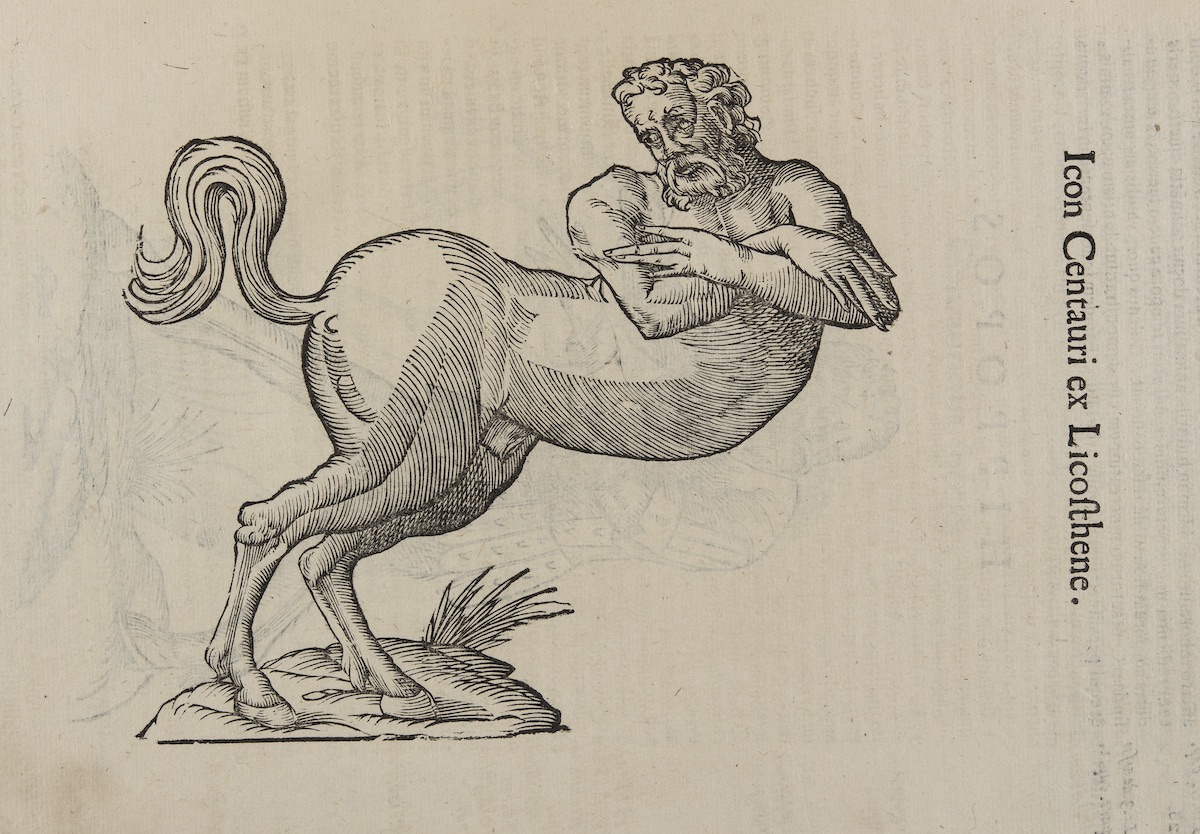

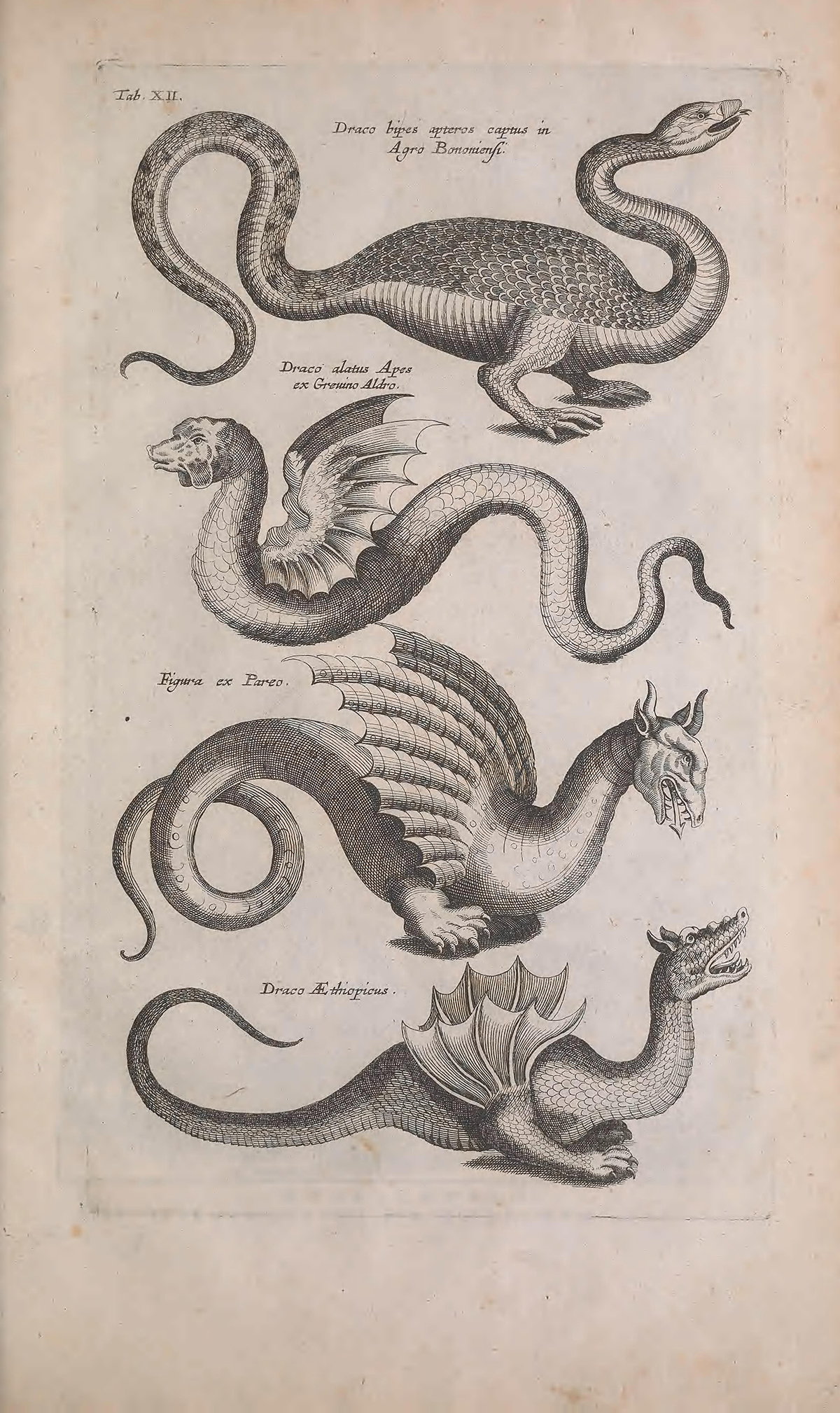

All the books are illustrated with memorable woodcuts. Many figures look like you’d expect them to – the fish, cow and humans looks familiar. And then you notice that a fish has a human face. You spot the massive, demented chicken. There’s a horse with human hands. There are dragons. The real and the imagined are mixed together so that things are presented as being of equal weight and truthfulness.

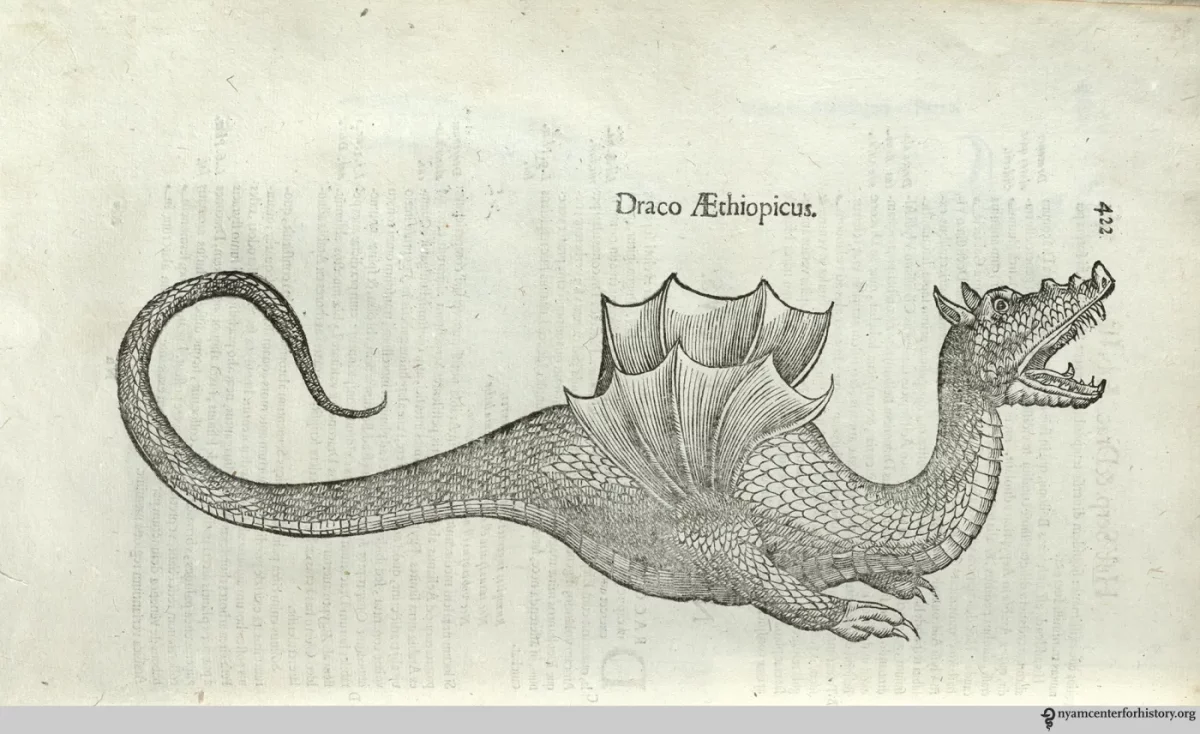

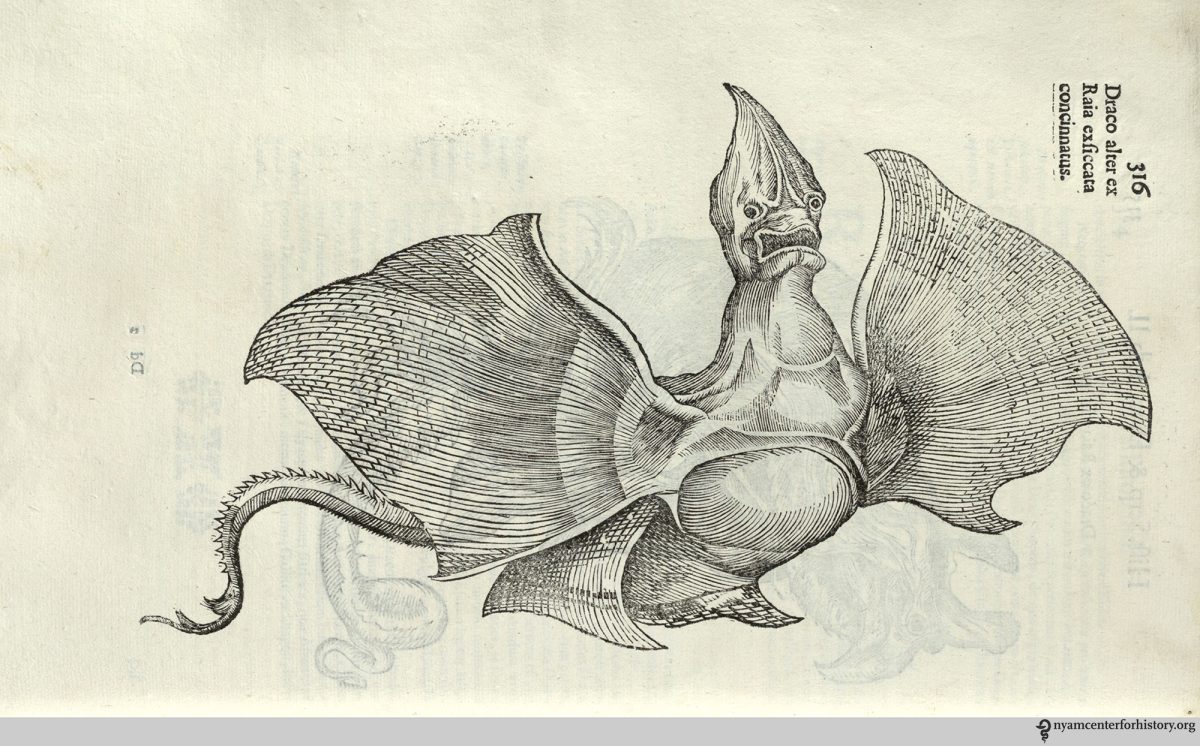

Although, Aldrovandi did say that one of his dragons was a Jenny Haniver (a fake). But then again he also stated that his Ethiopian dragon (below) was an authentic likeness of the real thing he’d seen with his own eyes.

Ulissi Aldrovandi

Aldrovandi was a revered naturalist, who, as legends has it, became interested in the natural world in 1550 while under a kind of house arrest for alleged heresy – which would have been a big deal given that Pope Gregory XIII was his cousin,

He became the University of Bologna’s first Professor of Natural Science. And he collected thousands of curious objects, work befitting a man who said: “I have never described any thing without first having seen it with my eyes.” Which is why he was able to draw a dragon from looking at the remains of the baby dragon he kept in a jar (below).

The Great Unknown

Not that Aldrovandi saw everything there was to see. Not all living things on Earth had been seen and identified. If he did see them, moving exotic creatures across land and sea was perilous and expensive. And the likeness of things depicted in art – those paintings and drawings of nature’s wonders – were hard to verify if only the artist had seen it. And what did we know changes – in Aldrovandi’s day, fossils were not viewed as the remains of living creatures, but “figured stones” that grew in the earth.

So Aldrovandi borrowed. Several of his quadrupeds in Aldrovandi’s books were copied from Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner’s banned Historia animalium (1558), Ambroise Paré’s Des monstres et prodiges (1573) and Pierre Belon’s 16th-century plates of human and bird skeletons.

We should recognise that Aldrovandi only oversaw the first four volumes of his work, which included, among most strange stuff, a rooster with a lion’s tale. And it’s the penultimate volume, compiled decades after his death by professors that contains the most bizarre specimens and the most reused images.

Via: University of Delaware, Alvin, Internet Archive

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.