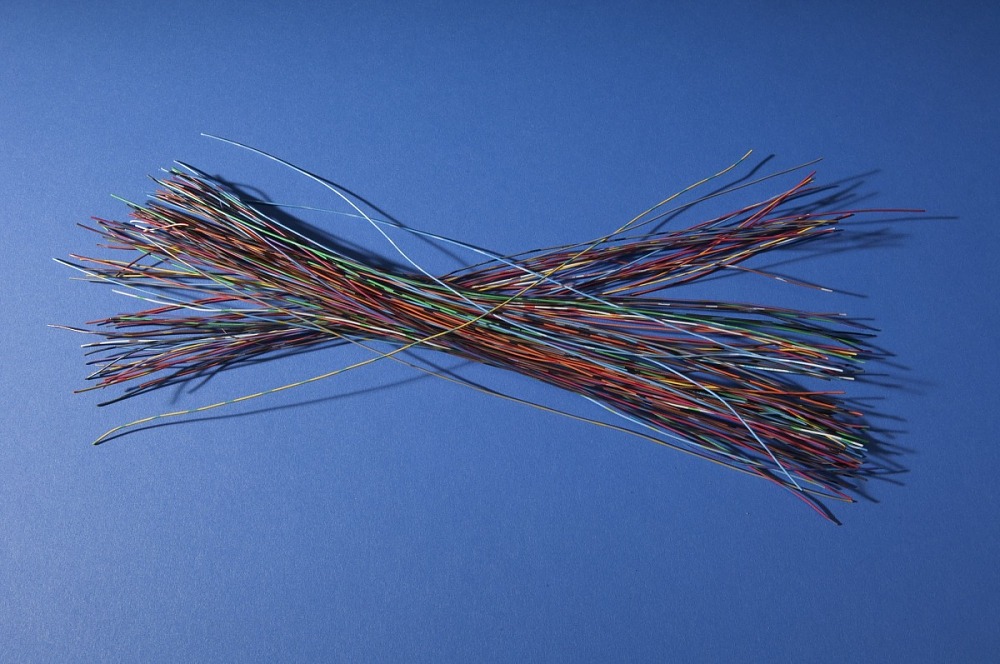

Grace Hopper (December 9, 1906 – January 1, 1992), a pioneering computer scientist and US Navy Rear Admiral, wanted to know what a nanosecond looked like. So she used wires to visualise it and other short durations of time.

She cut each wire to the maximum distance that light or electricity can travel in a nanosecond – one billionth of a second. Her wires would show computer programmers “just what they’re throwing away when they throw away a millisecond”, nanoseconds and other moments in time. They would also help military commanders understand why signals take so long to relay via satellite.

This bundle consists of about one hundred pieces of plastic-coated wire, each about 30 cm (11.8 in) long. Each piece of wire represents the distance an electrical signal travels in a nanosecond, one billionth of a second.

The Smithsonian Collection Website explains Hopper’s wires:

This bundle consists of about one hundred pieces of plastic-coated wire, each about 30 cm (11.8 in) long. Each piece of wire represents the distance an electrical signal travels in a nanosecond, one billionth of a second… [She] started distributing these wire “nanoseconds” in the late 1960s in order to demonstrate how designing smaller components would produce faster computers…

Later, as components shrank and computer speeds increased, Hopper used grains of pepper to represent the distance electricity traveled in a picosecond, one trillionth of a second (one thousandth of a nanosecond).

An enthusiastic teacher – as she said in 1980s: “I’ve come to feel that there is no use doing anything unless you can communicate” – in this video we see Hopper showing the wires to students in a lecture at MIT Lincoln Laboratory on 25 April 1985.

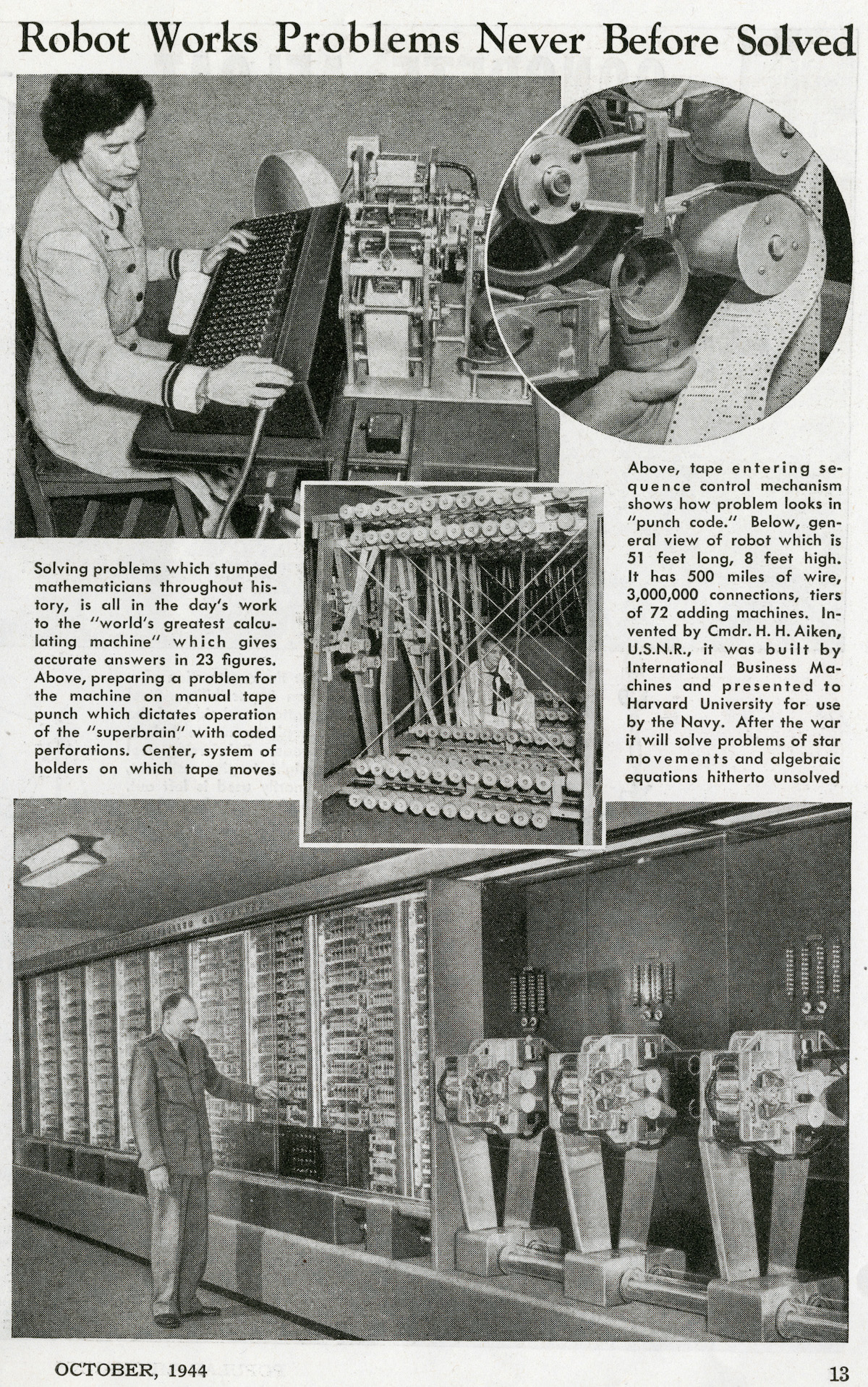

Grace Hopper was one of the first programmers of the Harvard Mark I computer, one of the earliest electromechanical computers, and invented compilers and machine independent programming languages, which underpin most of modern computing. She earned a Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale University and was a professor of mathematics at Vassar College before joining the Navy reserves during World War II.

The close relationship between the American military and the early computer industry, shaped Hopper’s career path. (Her great-grandfather, Alexander Wilson Russell, had been an admiral in the US Navy.)

Grace Hopper on page 13 of October 1944 Edition of Popular Mechanics.: “Robot Works Problems Never Before Solved”. Th ‘Harvard Calculator’ was 51 feet long, eight feet, high and weighed nearly five tons.

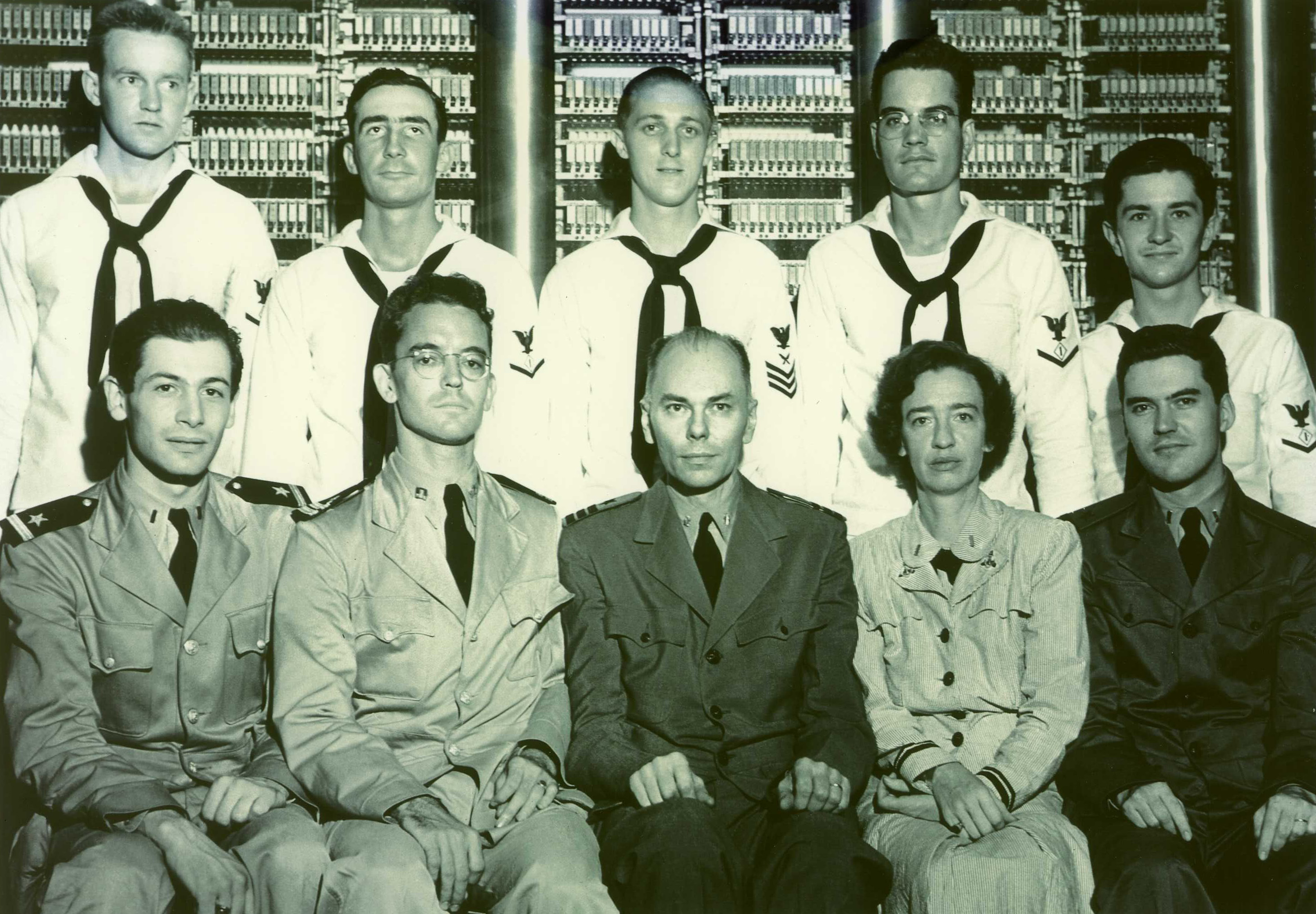

Grace Hopper & Cruft Research Lab colleagues with Mark I during World War II. (96-3277)

Hopper and her fellow officers in the Harvard lab worked on calculations essential to the war effort — computing rocket trajectories, creating range tables for new anti-aircraft guns, and calibrating minesweepers. They completed calculations for the army and “ran numbers” used by John von Neumann in developing the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan on 9 August 1945.

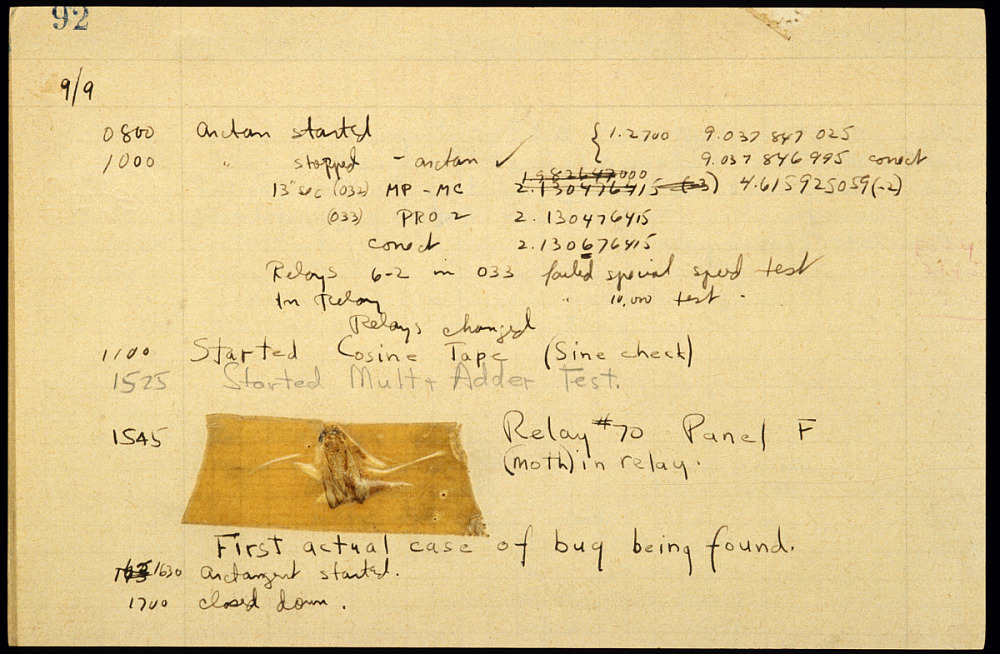

One evening in 1945 while working on the Mark II computer, Hopper and her colleagues encountered a problem. They took the machine apart and inside found a large moth. Although the term “bug” had been used by engineers since the 19th century to describe a mechanical malfunction, Hopper was the first to refer to a computer problem as a “bug” and to speak of “debugging” a computer.

In 1947, engineers working on the Mark II computer at Harvard University found a moth stuck in one of the components. They taped the insect in their logbook and labeled it “first actual case of bug being found.” The words “bug” and “debug” soon became a standard part of the language of computer programmers.

Here’s Hoppers talking to her fellow New Yorker David Letterman in 1986. A sharp mind and ready wit, her time wires appear just after the four minute mark:

See more at: Cartographies of Time: A Gorgeous Visual History of the Timeline

Via: National Museum of Medicine History.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.