“The Eye, that most amazing, that stupendous, that comprehending, that incomprehensible, that miraculous Organ, the Eye, is the Proteus of the Passions, the Herald of the Mind, The Interpreter of the Heart, and the Window of the Soul. The Eye has Dominion over all Things. The World was made for the Eye and the Eye for the World”

– The opening words in eye surgeon and chancer John Taylor of Norwich’s address to students at Oxford University

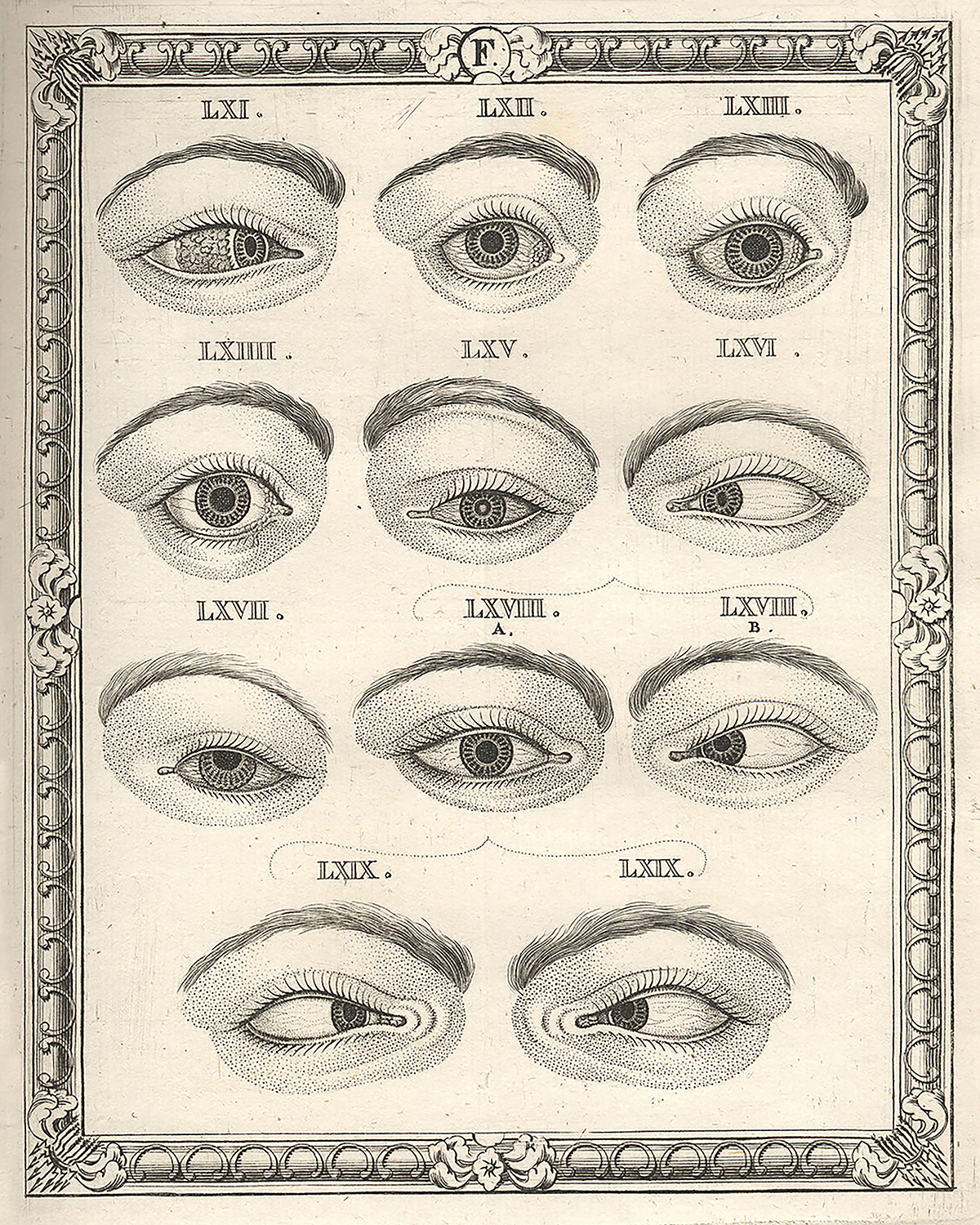

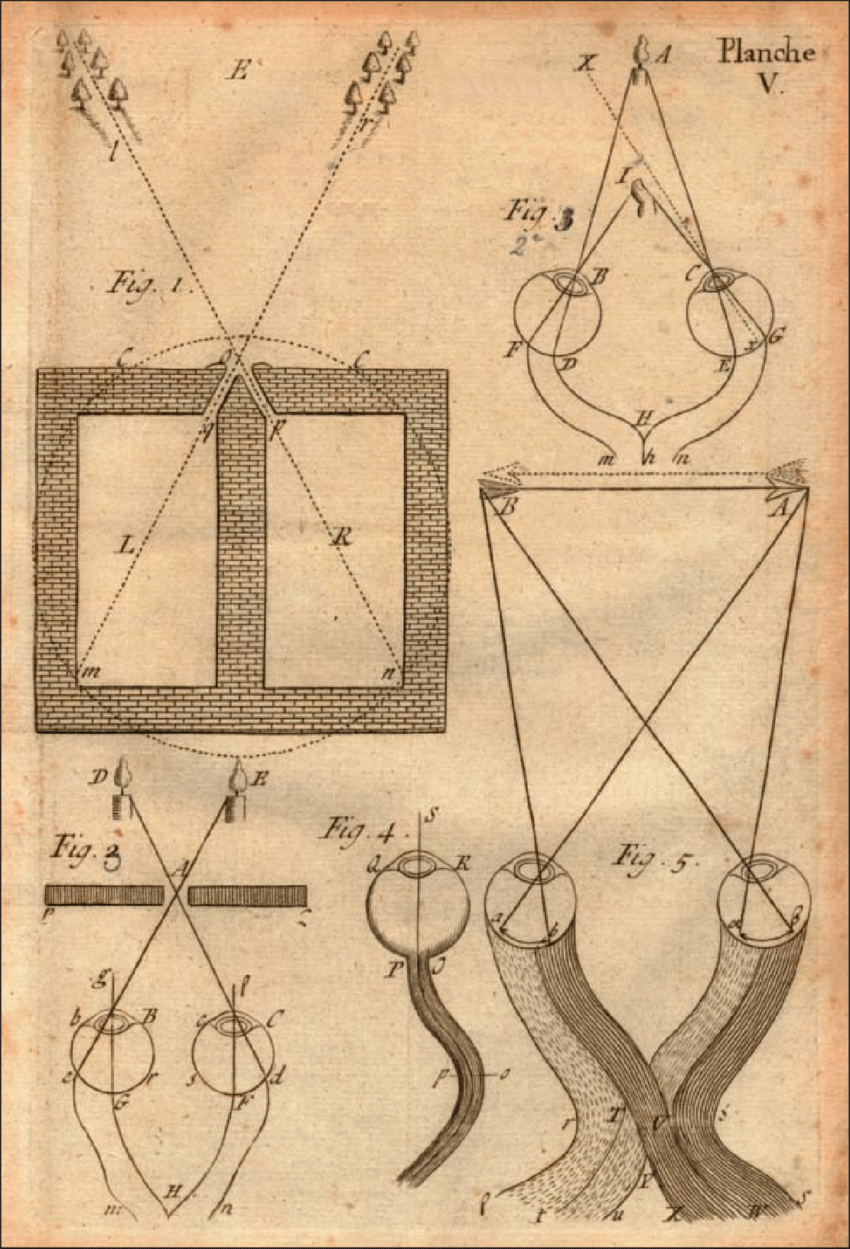

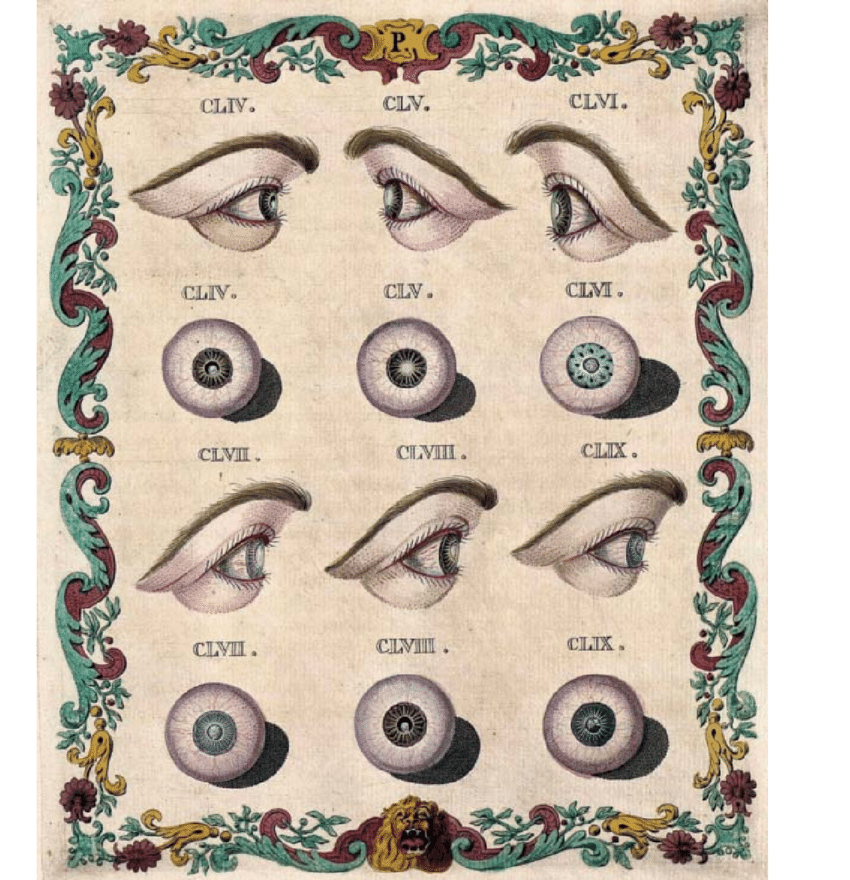

In 1766, John Taylor (1703-1772) delivered his work on ophthalmic nosography – “a detailed review of two hundred and forty-three affections, which can in any way injure the human eye and its neighbouring parts or take away the sight itself. Illustrated with icons most artistically carved and vividly expressed in colours with incredible accuracy.”

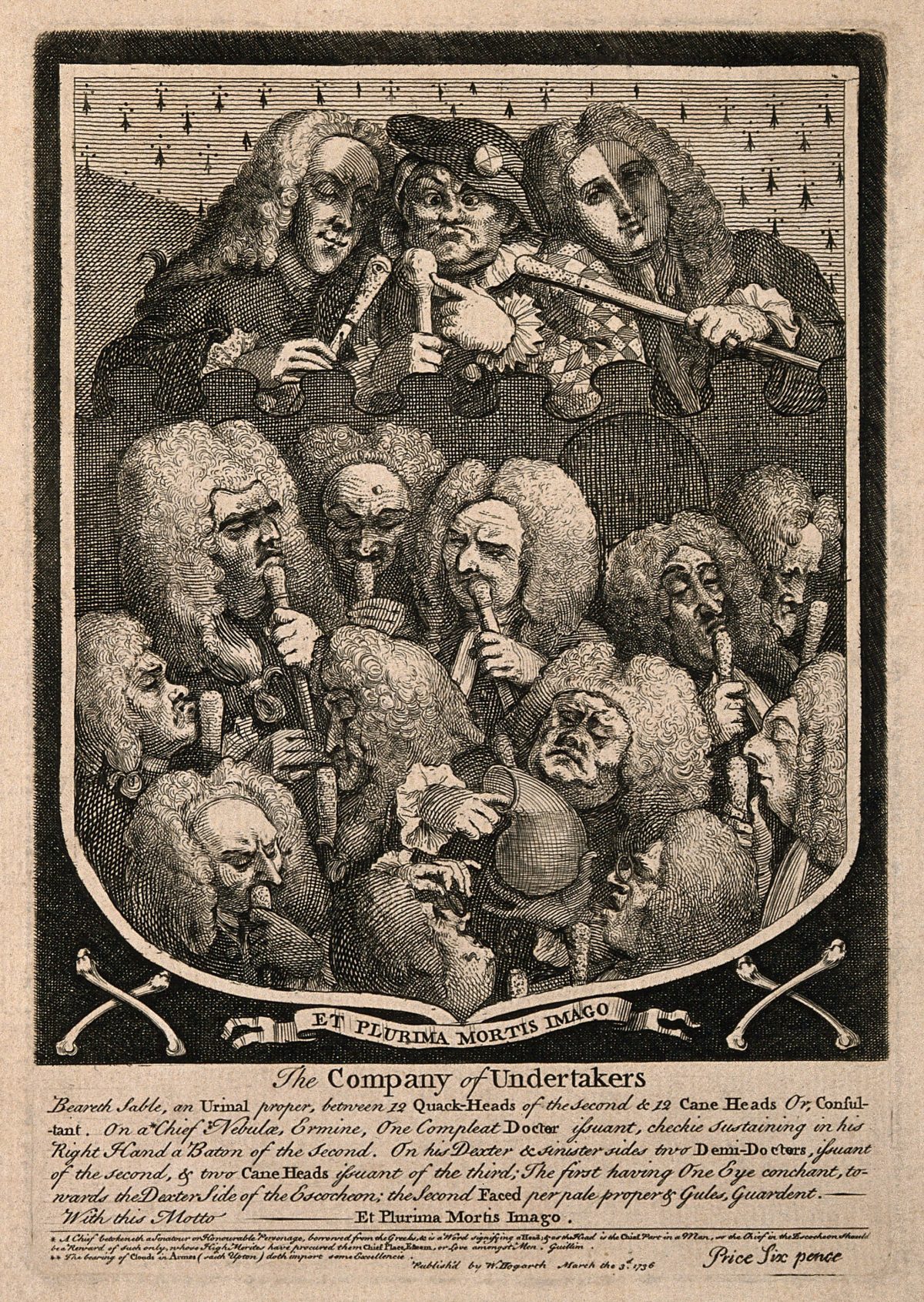

Well, so said Taylor, aka Chevalier Taylor, a man history records as an itinerant oculist and charlatan. The son of a surgeon in Norwich, England, Taylor studied under pioneering British surgeon William Cheselden at London’s St Thomas’ Hospital. In his huge 1761 autobiography in two volumes, The Life and Extraordinary History of the Chevalier John Taylor, Taylor styled himself “Ophthalmiater (sic) Pontifical, Imperial, Royal”.

Top man, then. But his titles were a blend of truth, self-aggrandisement and fakery.

The Chevalier John Taylor. Note the designation “Ritter”, German for “Chevalier”. From Taylor 1750c

The Mysterious Chevalier Taylor

John Taylor was appointed Royal Oculist to King George II in 1736. He was not commissioned by the reigning Holy Roman Emperor Francis I nor his wife Maria Theresia. In Vienna he had been admitted only to kiss their Majesties’ hands. His noble title Chevalier was self-styled and one he used from 1751. That same year, Taylor unsuccessfully treated the Duke of Mecklenburg, and the Duke’s physician Eschenbach found that Taylor’s Portuguese diamond-studded cross was mere jewellery and not a sign of Portuguese nobility. But in 1755 Taylor was ennobled by Pope Benedict XIV, thus earning his title.

His professional legacy is controversial, and stands accused by many contemporaries and historians of being a quack. Nevertheless, as Dr Christopher T. Leffler, of Virginia Commonwealth University, notes, “his writings demonstrate an understanding of ocular anatomy and disease better than that of most of his contemporaries”.

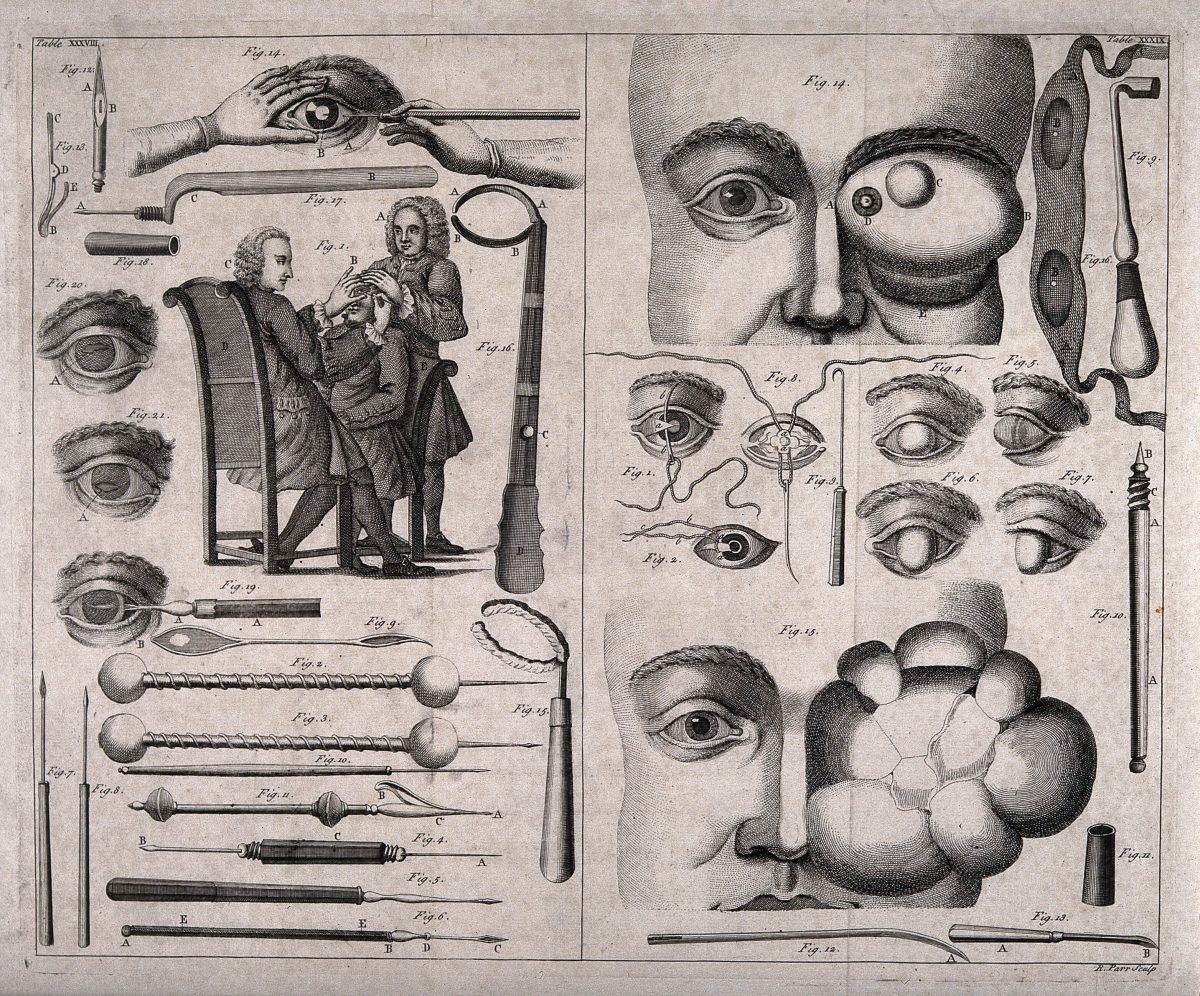

Ophthalmology instruments, eye growths, a cataract operation and other eye defects. Line engraving by R. Parr, 1743-45.

Taylor The Itinerant Charlatan

Taylor spent most of his life traveling throughout Europe and into Asia, ‘couching’ cataracts (often with disastrous results) – couching is the earliest documented form of cataract surgery and involved using sharp objects to push the cloudy part of the lens to the bottom of the eye or break it up.

He also sold his miraculous ointments and eye washes, including eye drops created from the blood of slaughtered pigeons.

Not that he was a lone rogue operator in a field of otherwise universal excellence. In the cartoon below, satirist Thomas Rowlandson (13 July 1757 – 21 April 1827) shows us eye lotion being made from urine in an English rural apothecary’s shop.

An English rural apothecary’s shop in which women apothecaries produce eye-lotion from their own urine. Watercolour by Thomas Rowlandson, ca. 1800

But Taylor does seem to have attracted more than his fair share of critics – and some of his overseas adventures appear to have been hastened by demands for payment back home. A 1761 official notice reported that “John Taylor … Doctor of Physick and [Oculist]” was reported among “Fugitives for Debt, and beyond the Seas … [who] intend to take the Benefit of an Act of Parliament … An Act for Relief of Insolvent Debtors”.

Dutch ophthalmologist R. Zegers mentions that “after his training, Taylor started practicing in Switzerland, where he blinded hundreds of patients”. English writer Samuel Johnson said Taylor’s life showed “an instance of how far impudence may carry ignorance”.

During his second visit to Ireland in March and April of 1732, Taylor was attacked in George Faulkner’s Dublin Journal as “a person of unparallel’d impudence, undeniable assurance, an asserter of scandalous falsehoods, a mountebank, and a quack, who imposes on the public and extorts money from the poor”.

The French surgeon Pierre Guérin described how Taylor would bind his patients’ couched eyes with gauze that included egg white, baked apple, or salt, and sometimes a coin: “He would exalt; he would proclaim a miracle; he plugged the eye with firm recommendation not to uncover it until after five or six days, and he left on the fourth, after having exploited the victims of his bad faith.”

Qui dat videre dat vivere

Taylor travelled faster and further than his patient screams could carry. Lest you miss the coming of the man who could cure your eye disease, he would arrive in a coach decorated with eyes and the motto ‘Qui dat videre dat vivere’ (to give sight is to give life).

He did enjoy some medical success. Nicholas J Wade, of the University of Dundee, tells us that Taylor’s “operations on the eye were probably no less successful than those of his contemporaries, and his treatment of strabismus contained ideas that were to take a century to become incorporated into ophthalmology (Hirschberg 1984). His occasional insights should not be overshadowed by his astonishing arrogance.

And he treated English historian Edward Gibbon (8 May 1737 – 16 January 1794) successfully for cataracts. Taylor was the first surgeon supposedly to attempt operations for the squint.

The Oxford academic William King (1685-1763), in his memoirs, discussed his experiences with Taylor. King wrote of a relative, Sir William Smyth, who was successfully couched by Taylor – “Sir William was able to read and write without the use of spectacles during the rest of his life” – but cheated Taylor out of most of his surgical fee by feigning persistent visual loss. King’s description of Taylor is worth repeating:

“He seems to have understood the anatomy of the eye perfectly well; he has a fine hand and good instruments, and performs all his operations with great dexterity; for the rest, Ellum homo confidens! [Look, there is a confident man!] who undertakes anything (even impossible cases) and promises every thing. No charlatan ever appeared with fitter and more excellent talents, or to a greater advantage.”

Diagram of diseases of the lens from Taylor’s Atlas “Nova Nosographia Ophthalmica”

Blind Faith

But his treatment of German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (31 March 1685 – 28 July 1750) was unsuccessful, and it has been argued that he brought the composer’s life to an earlier end – Bach died four months after Taylor worked on his cataracts in Leipzig. He treated the German-British composer Georg Friedrich Handel (23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759), which apparently occasioned the composer’s complete blindness.

Not that blinding two hymned composers was any barrier to his ego. As Taylor wrote in his autobiography:

“…I have seen a vast variety of singular animals, such dromedaries, camels and particularly at Leipsick, where a celebrated master of music, who had already arrived to his 88th year, he received his sight by my hands; it is with this very man that famous Handel was first educated, and with whom I once thought to have had the same success, having all circumstances in his favour, motions of the pupil, light etc but upon drawing the curtain, we find the bottom defective, from a paralytic disorder… ”.

In case you missed that, Taylor wrote a poem dated August 15, 1758, and published in the London Chronicle of August 24, 1758, in which he celebrates his ability to restore Handel’s sight. In the poem Euterpe calls Apollo and Aesculapius to help the blind Handel but Apollo replies that Aesculapius is not necessary because The Chevalier Taylor will do it.

The Mysterious Death of Chevalier Taylor

In 1741 “the greatest charlatan among all oculists who ever lived” appeared in Rouen and was treated to a splendid lunch by a famed and skilful French surgeon known as ‘Le Cat’. When the dome over the plate of desert was lifted it revealed a human skull in which the nerves to the extraocular muscles were dissected, demonstrating conclusively that none could have been excised by Taylor’s method. Legend has it that the charlatan was annihilated and within four days his reputation was ruined.

But that is uncertain. And even his death is unclear. The time and place of Taylor’s death is a matter of debate. The musicologist Charles Burney said that Taylor died on Friday 16 November 1770 in Rome. He was also said to have died in Paris. In June and July 1772, newspapers in Germany and England reported that he died at a convent in Prague, completely blind.

Via: The Taylor Dynasty: Three Generations of 18th-19th Century Oculists by Stephen G. Schwartz, MD, MBA1 ; Christopher T. Leffler, MD, MPH2; Andrzej Grzybowski, MD, PhD, MBA3,4 ; Hans-Reinhard Koch, MD5 ; Dennis Bermudez1

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.