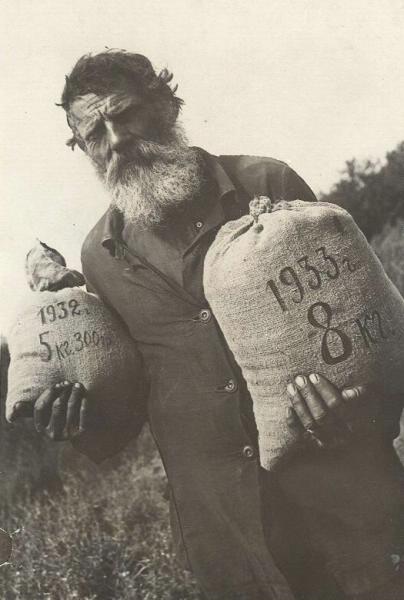

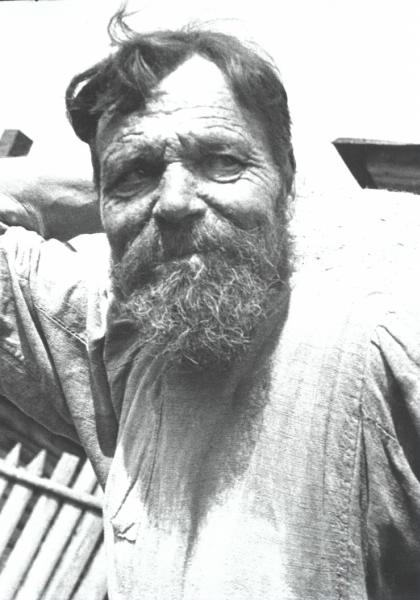

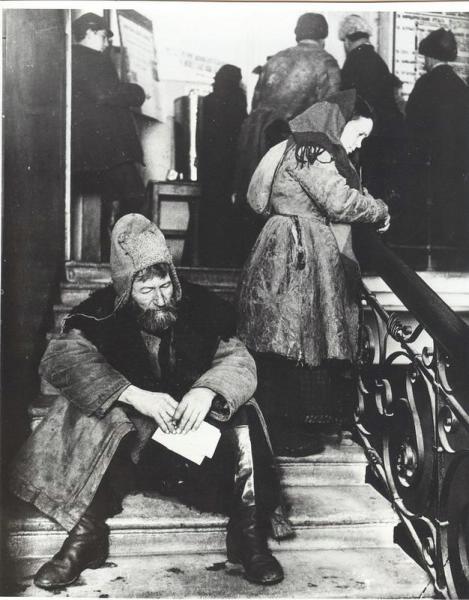

The Great Break. From the surplus to total collectivization – these photos record the transformation of the Russian peasant into the collective farmer. Not everyone was for the project that followed the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War (1918–1921). The wealthier farmers – the land-owning kulaks who wanted the right to trade and eat their own crops. – were subjected to arrest, deportation and execution.

Collectivisation was unveiled as state policy in 1927. But after two years of resistance, Joseph Stalin decreed that the kulak class must be liquidated. On 27 December 1929, he said:

“Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes.”

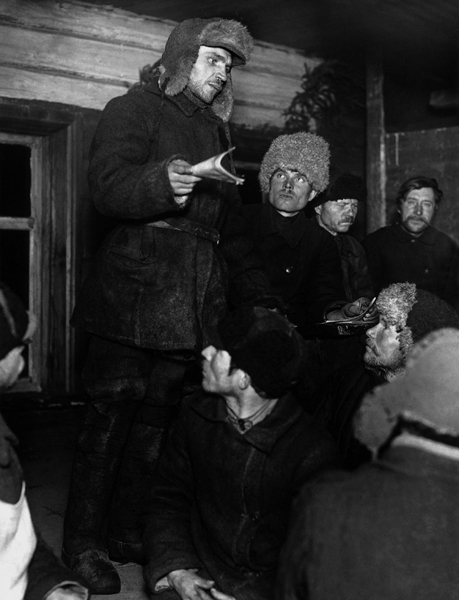

Shebboldaev, party secretary for the North Caucasus, enlarged on this drive for total control:

“At the present moment, when what remains of the kulaks are trying to organise sabotage, every slacker must be deported. That is true justice. You may say that before we exiled individual kulaks, and that now it concerns whole stanitza [villages] and whole collective farms. If these are enemies they must be treated as kulaks.”

Did it work?

Collectivization was the main cause of a famine that killed millions of people in Ukraine, the Soviet breadbasket, in 1932 and 1933.

By 1939, 99 per cent of land had been collectivised 90% of the peasants lived on one of the 250,000 kolkhoz. Farming was run by government officials. The government took 90 per cent of production and left the rest for the people to live on.

Ukraine’s Stalin-era famine is known as the Holodomor (“death by hunger”).

When in 1932 the grain harvest did not meet the Kremlin’s targets, activists were sent to the villages where they confiscated not just grain and bread, but all the food they could find.

The confiscations continued into 1933, and the results were devastating. No-one is sure how many people died, but historians say that in under a year at least three million and possibly up to 10 million starved to death.

The horrors Ekaterina saw live with her still.

“We didn’t have any funerals – whole families died,” she tells me.

“Of our neighbours I remember all the Solveiki family died, all of the Kapshuks, all the Rahachenkos too – and the Yeremo family – three of them, still alive, were thrown into the mass grave.”

Ekaterina, her mother and brother, survived by eating tree bark, roots and whatever they could find – but she says starvation drove others to terrible deeds.

“One day mother said to us, ‘children, you can’t take your usual shortcut through the village anymore because the grandpa in the house nearby killed his grandson and ate him – and now he’s been killed by his son… – BBC

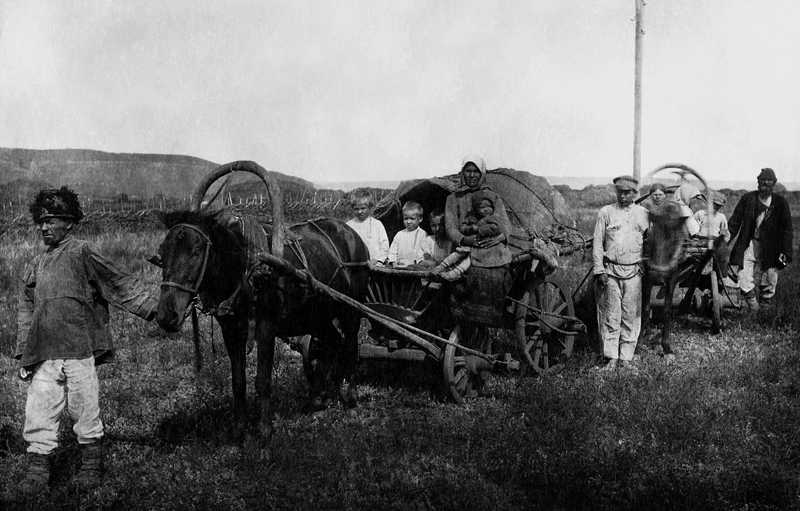

Organization of the collective farm in the homeland of the writer Mikhail Sholokhov in Veshenskaia

Date: 1930

Cabin Larin Chairman of the Board of machine association Ippolitova

Smolensk Province., Der. Larino. Date: 1925

Date: 1919 – 1921

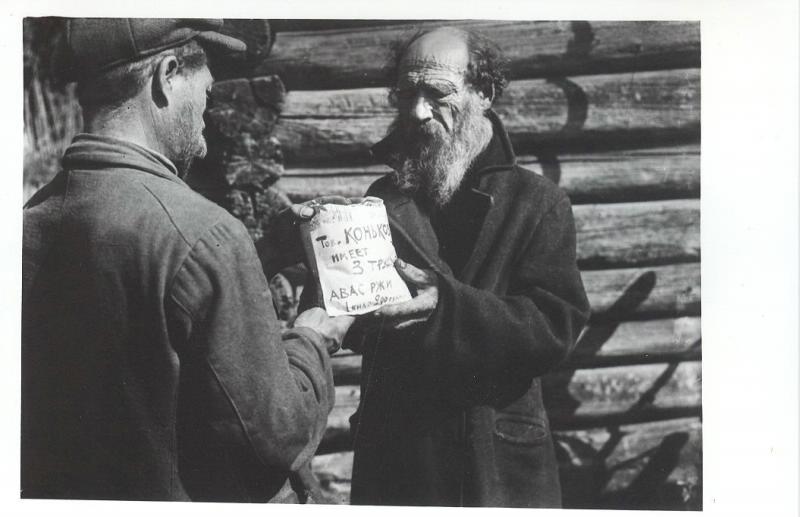

The inscription on the package: “. Comrade Kon’kov has 3 workdays Awas RYE 1 kilo 200 grams.” Tver Province. Kimry

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.