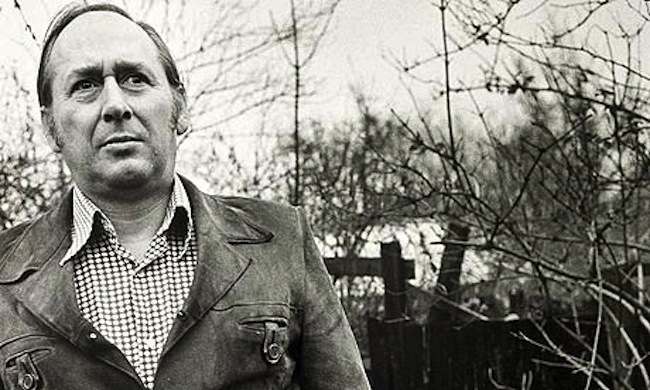

In 1966, readers of issue 164 of New Worlds magazine (1946 – 1997) could enjoy writer JG Ballard’s (15 November 1930 – 19 April 2009)review of La Jetée, the time-travel short by Chris Marker about time and memory which was receiving its first London screenings and his essay ‘The Coming of the Unconscious‘. In it, the British author writes about the surrealist paintings that influenced much of his early fiction.

As the JG Ballard website notes:

While ostensibly a review of two books, this is really an opportunity for JGB to expound on one of his favourite topics: “The pervasiveness of surrealism is proof enough of its success. The landscapes of the soul, the juxtaposition of the bizarre and familiar, and all the techniques of violent impact have become part of the stock-in-trade of publicity and the cinema, not to mention science fiction”.

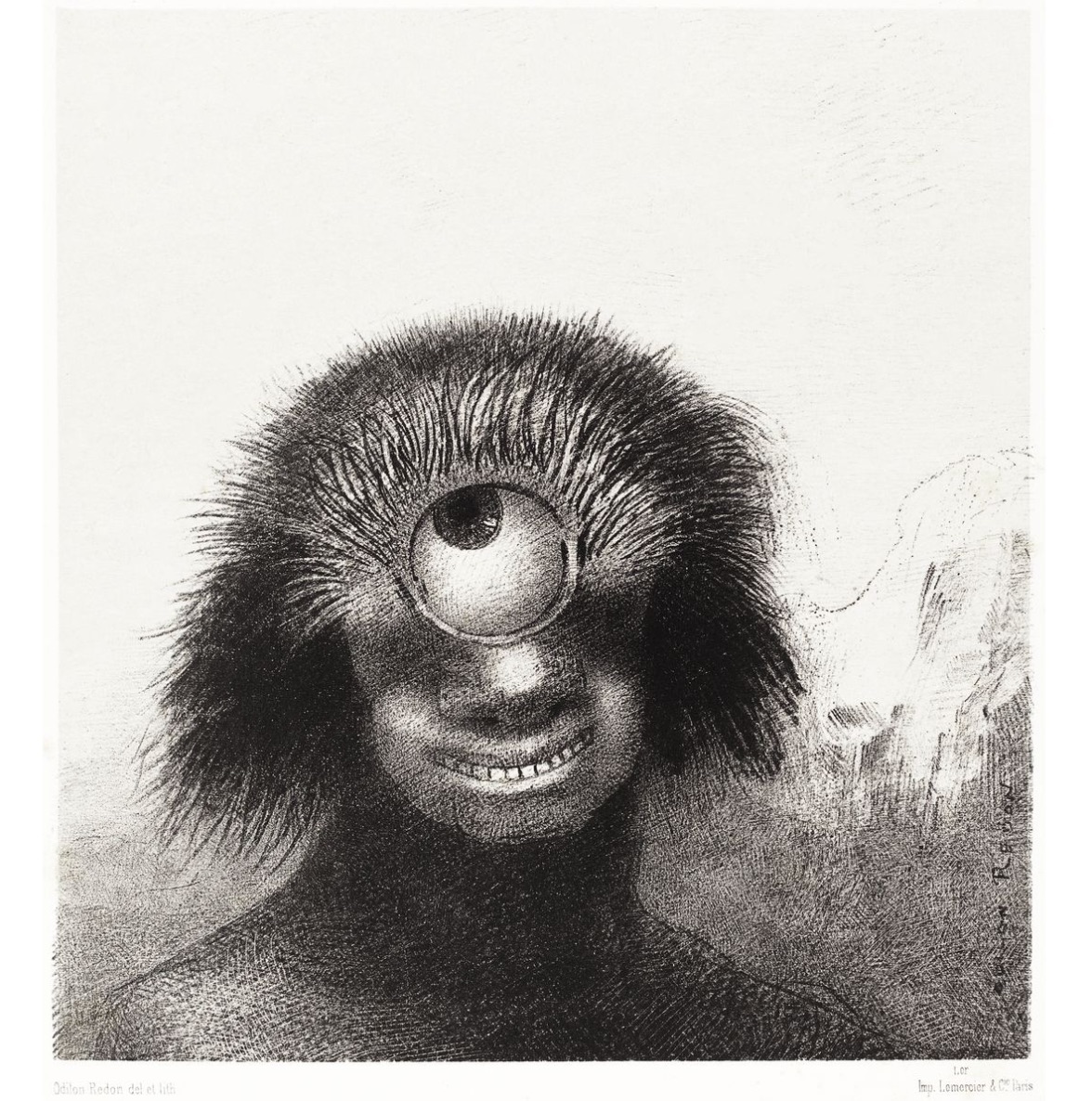

Ballard begins his look on the power and relevance of surrealism by quoting to the French symbolist artist Odilon Redon (20 April 1840 – 6 July 1916):

The images of surrealism are the iconography of inner space. Popularly regarded as a lurid manifestation of fantastic art concerned with states of dream and hallucination, surrealism is in fact the first movement, in the words of Odilon Redon, to place “the logic of the visible at ‘the service of the invisible.”…

What uniquely characterises this fusion of the outer world of reality and the inner world of the psyche (which I have termed “inner space”) is its redemptive and therapeutic power. To move through these landscapes is a journey of return to one’s innermost being.

John Coulthart adds that the list does not include all surreal art that shaped Ballard’s thinking:

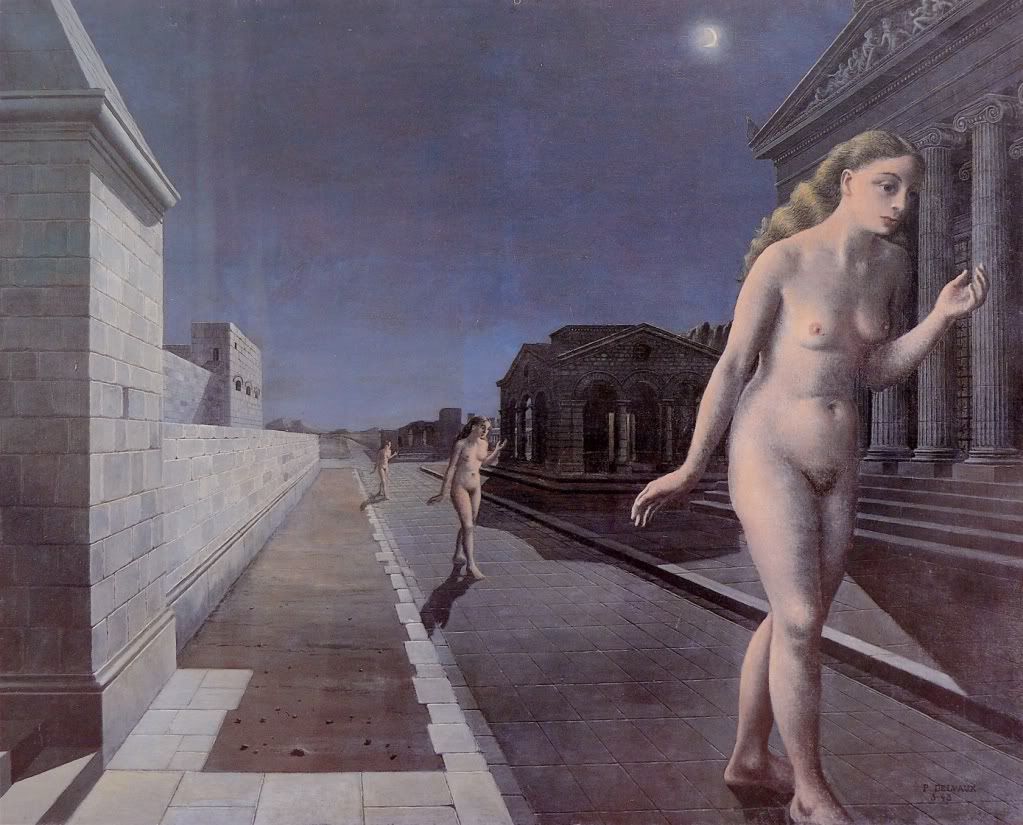

The following list comes near the end of the piece, and shouldn’t be taken as a definitive selection on Ballard’s part. There’s no Yves Tanguy, for example, even though Tanguy’s art is referred to in The Drought. And no Paul Delvaux either, an artist who Ballard liked enough to commission Brigid Marlin to recreate the two Delvaux paintings that were destroyed in the Second World War. A still-extant Delvaux painting, The Echo, is mentioned in The Day of Forever, a story that Ballard was probably writing around this time and which was published in New Worlds 170.

Giorgio de Chirico: The Disquieting Muses.

An undefined anxiety has begun to spread across the deserted square. The symmetry and regularity of the arcades conceals an intense inner violence; this is the face of catatonic withdrawal. The space within this painting, like the intervals within the arcades, contains an oppressive negative time. The smooth, egg-shaped heads of the mannequins lack all features and organs of sense, but instead are marked with cryptic signs. These mannequins are human beings from whom all transitional time has been eroded, they have been reduced to the essence of their own geometries.

Max Ernst: The Elephant of Celebes.

A large cauldron with legs, sprouting a pipe that ends in a bull’s head. A decapitated woman gestures towards it, but the elephant is gazing at the sky. High in the clouds, fishes are floating. Ernst’s wise machine, hot cauldron of time and myth, is the tutelary deity of inner space, the benign minotaur of the labyrinth.

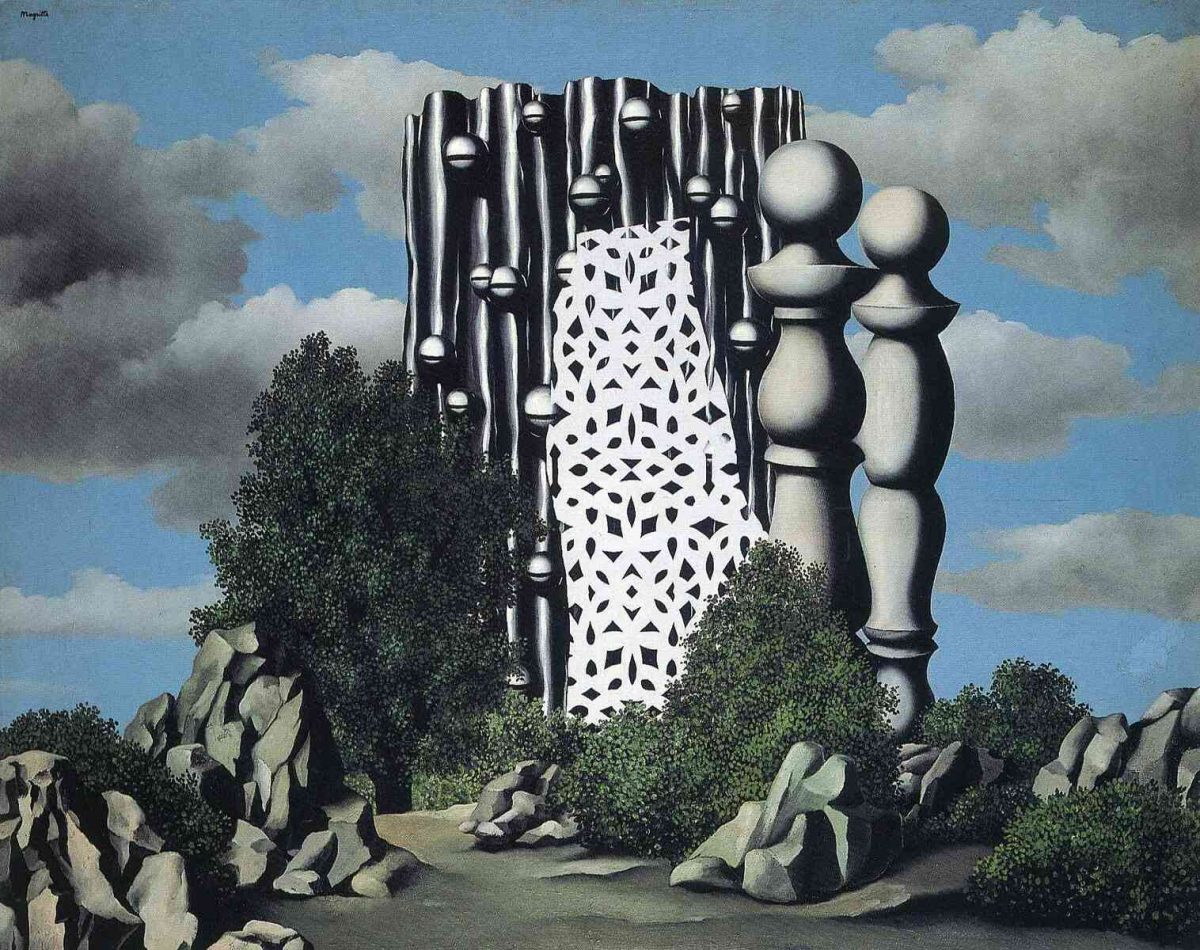

René Magritte: The Annunciation.

A rocky path leads among dusty olive trees. Suddenly a strange structure blocks our way. At first glance it seems to be some kind of pavilion. A white lattice hangs like a curtain over the dark facade. Two elongated chess-men stand to one side. Then we see that this is in no sense a pavilion where we may rest. This terrifying structure is a neuronic totem, its rounded and connected forms are a fragment of our own nervous systems, perhaps an insoluble code that contains the operating formulae for our own passage through time and space. The annunciation is that of a unique event, the first externalisation of a neural interval.

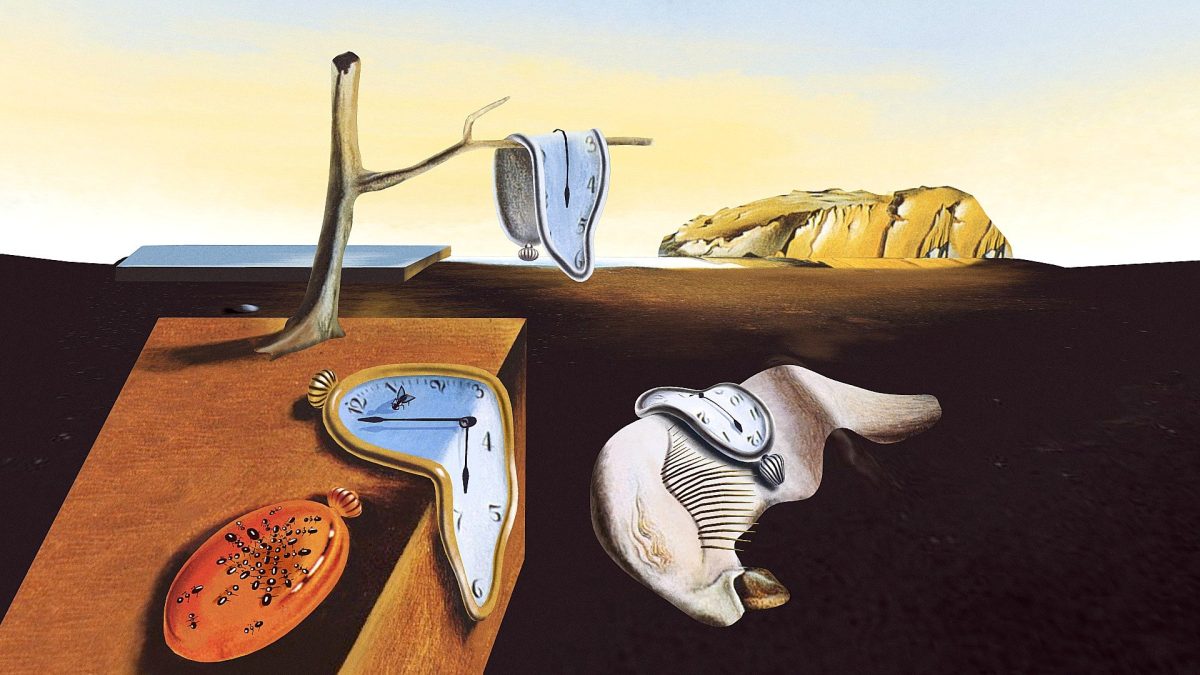

Salvador Dali: The Persistence of Memory.

The empty beach with its fused sand is a symbol of utter psychic alienation, of a final stasis of the soul. Clock time here is no longer valid, the watches have begun to melt and drip. Even the embryo, symbol of secret growth and possibility, is drained and limp. These are the residues of a remembered moment of time. The most remarkable elements are the two rectilinear objects, formalisations of sections of the beach and sea. The displacement of these two images through time, and their marriage with our own four-dimensional continuum, has warped them into the rigid and unyielding structures of our own consciousness. Likewise, the rectilinear structures of our own conscious reality are warped elements from some placid and harmonious future.

Oscar Dominguez: Decalcomania.

By crushing gouache Dominguez produced evocative landscapes of porous rocks, drowned seas and corals. These coded terrains are models of the organic landscapes enshrined in our central nervous systems. Their closest equivalents in the outer world of reality are those to which we most respondigneous rocks, dunes, drained deltas. Only these landscapes contain the psychological dimensions of nostalgia, memory and the emotions.

Max Ernst: The Eye of Silence.

This spinal landscape, with its frenzied rocks towering into the air above the silent swamp, has attained an organic life more real than that of the solitary nymph sitting in the foreground. These rocks have the luminosity of organs freshly exposed to the light. The real landscapes of our world are seen for what they are — the palaces of flesh and bone that are the living facades enclosing our own subliminal consciousness.

Ballard ends with an observation about his age – he could be speaking of current times:

The techniques of surrealism have a particular relevance at this moment, when the fictional elements in the world around us are multiplying to the point where it is almost impossible to distinguish between the “real” and the “false” — the terms no longer have any meaning. The faces of public figures are projected at us as if out of some endless global pantomime, they and the events in the world at large have the conviction and reality of those depicted on giant advertisement hoardings. The task of the arts seems more and more to be that of isolating the few elements of reality from this melange of fictions, not some metaphorical “reality,” but simply the basic elements of cognition and posture that are the jigs and props of our consciousness.

Paul Delvaux, The Echo

Surrealism offers an ideal tool for exploring these ontological objectives: the meaning of time and space (for example, the particular significance of rectilinear forms in memory), of landscape and identity, the role of the senses and emotions within these frameworks. As Dali has remarked, after Freud’s explorations within the psyche it is now the outer world which will have to be eroticised and quantified. The mimetising of past traumas and experiences, the discharging of fears and obsessions through states of landscape, architectural portraits of individuals — these more serious aspects of Dali’s work illustrate some of the uses of surrealism. It offers a neutral zone or clearing house where the confused currencies of both the inner and outer worlds can be standardised against each other.

At the same time we should not forget the elements of magic and surprise that wait for us in this realm. In the words of Andre Breton: “The confidences of madmen: I would spend my lite in provoking them. They are people of scrupulous honesty, whose innocence is only equalled by mine. Columbus had to sail with madmen to discover America.”

‘The Coming of the Unconscious’ was reprinted several times after its first appearance: in a story collection, The Overloaded Man (1967) and in the essay and reviews collection A User’s Guide to the Millennium (1996).

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.