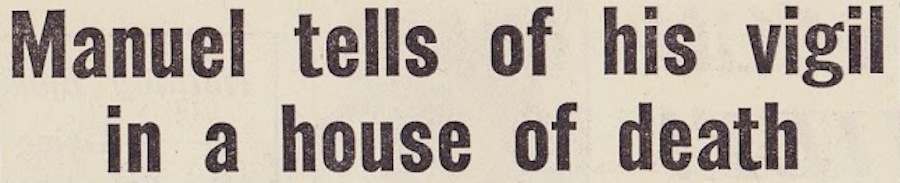

Picture the scene: New Year’s Day, 1958, a killer sits at a breakfast table eating a bowl of children’s cereal. The house is quiet, the curtains drawn–it’s early morning, still dark outside–the rain lightly drums on the glass. Downstairs, there is no sign of a struggle, everything as it was the night they went to bed. At some point during the night, the killer had broken into the house, quietly climbed the stairs and shot the mother and the father, then their son, as they slept. Now he ate breakfast cereal and thought how nice it would be to live in a house like this–tidy, secure, hidden. The family cat nuzzled against his leg. He poured some milk into a bowl and watched as the cat lapped it up.

The killer was Peter Manuel. The family he had just killed was Peter and Doris Smart, and their ten-year-old son, Michael. He stayed in the house for almost a week. No one noticed the family’s absence–neighbours had thought the Smarts had gone away for New Year. It was one of the many elements of chance that helped Manuel in his two-year trail of murder that terrorised Glasgow’s suburbs in the late 1950s.

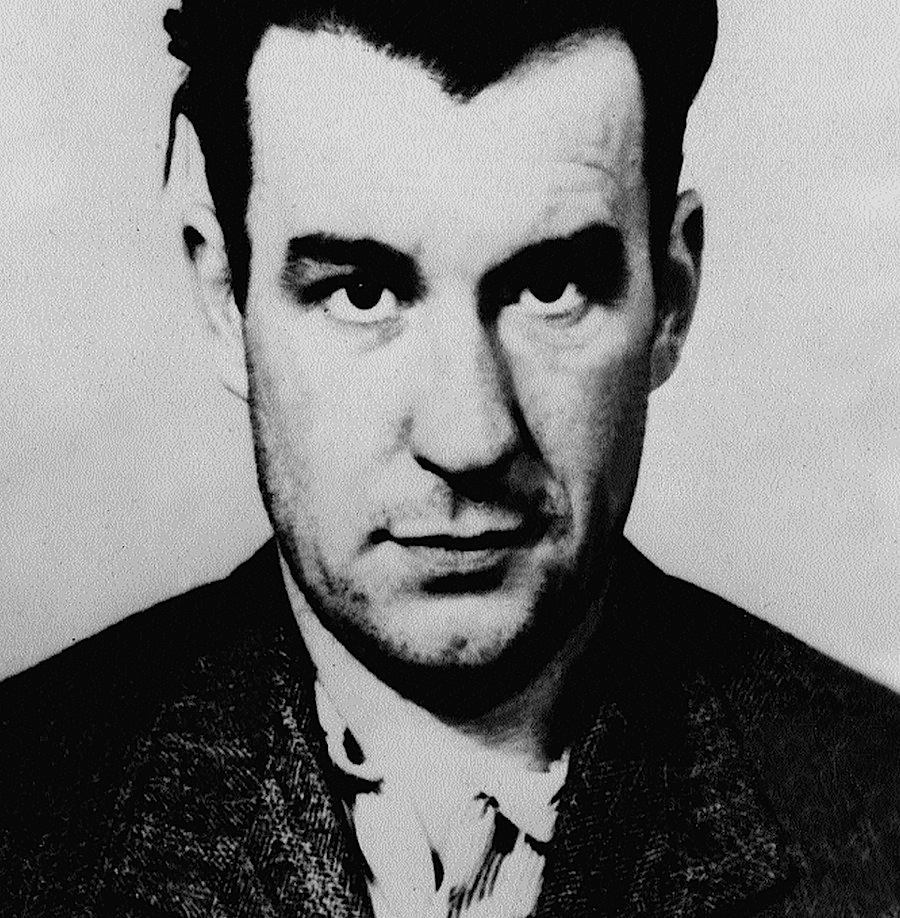

Manuel was a callous killer and sexual predator, who carried out eight brutal murders with chilling indifference. He was born in Manhattan in 1927 to Scottish parents. At the age of five, his parents returned to Scotland. Manuel had a high IQ, was considered a talented artist and musician, and was proficient enough to be considered as a professional boxer. Instead, Manuel opted for a life of easy money and violent sex.

His first victim was seventeen-year-old Anne Kneilands. He met her by chance in January 1956, when a man she had met at a dancehall had failed to turn up for a date. If her date had turned up, Anne would be alive today. Instead she met Manuel, who raped and murdered her, dumping her partially clothed body on a golf course.

The police considered it a one-off crime, but had they been more assiduous, then Manuel would have been stopped before he killed seven others.

At the time Kneilands’ body was found, Manuel was being interviewed by police in connection with the theft of property from the Gas Board. Constable James Jardine, who interviewed Manuel and his fellow workers, noted that Manuel’s face was covered in scratches. Jardine didn’t believe Manuel’s excuse that he had been in a fight. However, he did not connect Manuel as possible suspect in the violent killing of Kneilands–even though Manuel had already served eight years for rape, and been known as a violent sexual predator from the age of fifteen.

Manuel’s main criminal activity was as a housebreaker. In September 1956, he heard through underworld contacts that William Watt, a master baker, had left his family to take a short fishing holiday. Manuel took this opportunity to break into the Watt’s home in High Burnside and murder its occupants: wife Marion (45), daughter Vivienne (16), and sister-in-law, Margaret Brown. Marion and Margaret had been shot while sleeping. Vivienne had been violently assaulted and stripped. The similarity between Vivienne’s death and Anne Kneilands should have been apparent, and while some detectives considered Manuel as a possible perpetrator, perceived inconsistencies William Watt’s alibi and the use of a gun, led the police to arrest Watt for the murders.

In early December 1957, Manuel attended a job interview in Newcastle. At some point during his visit, Manuel killed taxi driver Sydney Dunn (36) on the 8th December, dumping his body on moorlands in Northumbria. As there was no pattern to Manuel’s killing spree, police did not connect him with this murder, until a button matching one of Manuel’s jackets was found in Dunn’s car.

Twenty days later, Manuel attacked and strangled Isabella Cooke (17) in Uddingston, near Glasgow. Again, the victim had been stripped, beaten, raped and strangled, her body buried in farmland. With no body, the police did not at first consider Cooke had been murdered. They were also no closer to suspecting the involvement of Manuel.

On New Year’s Day 1958, Manuel broke into the house of Peter and Doris Smart–killing all three members of the family as they slept. Manuel hid out in the house. When he eventually left, he stole newly issued banknotes from Peter Smart’s wallet and the family car from the garage. On his drive to Glasgow, Manuel gave a lift to an off-duty police constable, Robert Smith. The two men discussed Isabella Cooke’s disappearance and possible murder, with Manuel telling Smith the police were looking in the wrong place for the young girl.

The murder of the Smart family led the press to describe the brutal killer as “The Beast of Birkenshaw.” Police were having still having no luck in finding the killer, until the Smart’s car was found abandoned in the Gorbals district of Glasgow. Manuel’s luck was about to end, as Constable Smith recognised the car as the same one he had been given a lift in, and quickly identified Manuel as its driver.

Again, the police did not think Manuel was a killer, believing him to be first and foremost a burglar. However, their suspicions were compounded by two incidents. The first was when Manuel used money from the Smart murders in a hotel bar. As these banknotes had been newly issued the bank numbers were known to police. The second bizarre incident involved Manuel approaching William Watts’ lawyer claiming he had information as to the identity of the Watt family killer. Manuel appeared to be toying with the police when he gave the lawyer a statement which revealed significant information that only the killer could have known. The police arrested Manuel on the theft of money and a car, but this soon proved enough for Manuel to confess to the eight murders.

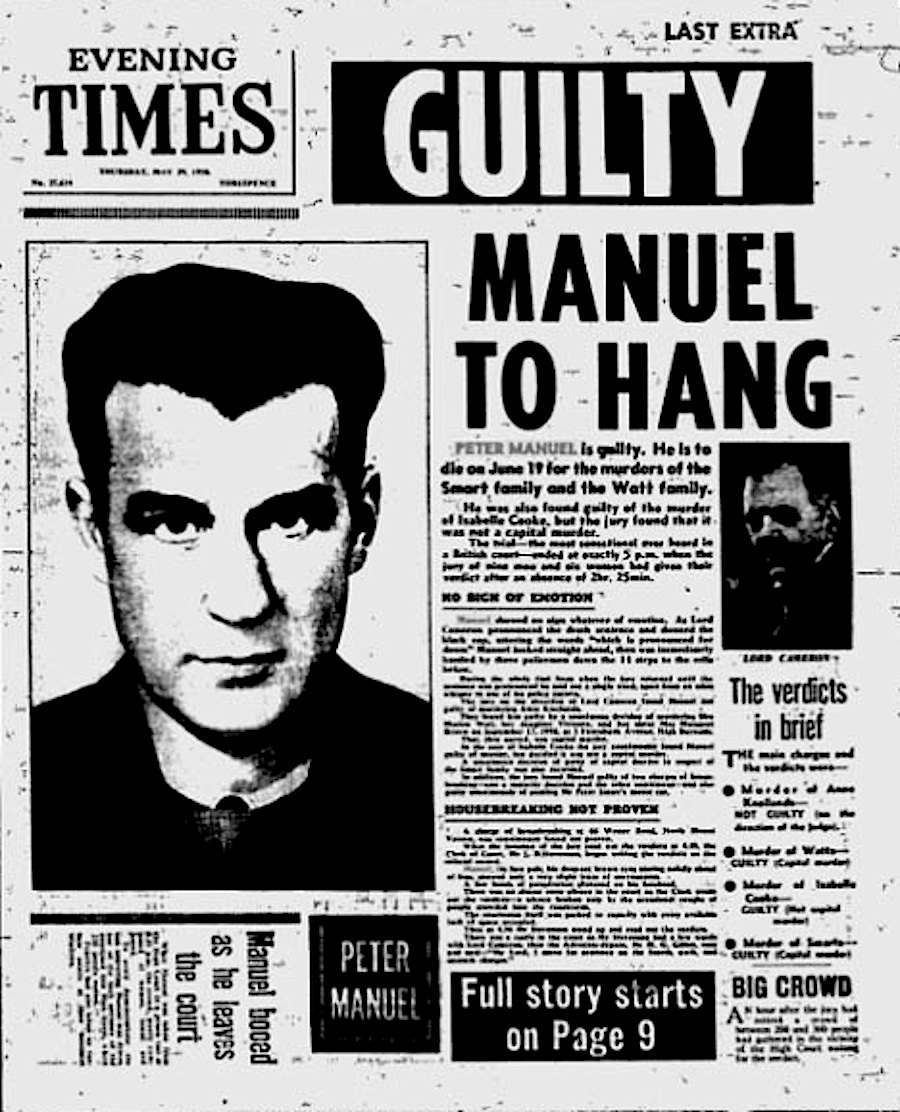

At his trial, Manuel became the first man accused of murder to dismiss his lawyers and defend himself. Manuel claimed his confession had been forced out of him and blamed William Watt for the murders. However, the police had decided to charge Manuel with housebreaking as well as murder, as the method of breaking and entering had been the same in the both the Watt and Smart families murders.

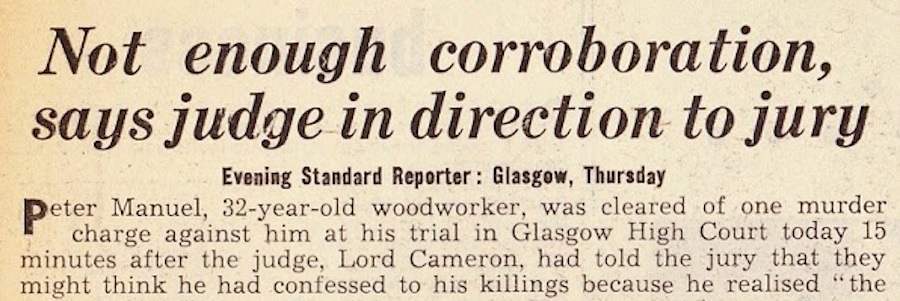

At the trial, the judge cleared Manuel of the murder of Anne Kneilands, though Manuel had confessed to the crime. The judge declared there was no evidence to prove a link between the two. However, the evidence amassed against Manuel was damning enough to see him convicted of seven murders and he was sentenced to death.

Manuel was Scotland’s first convicted serial killer. He was hung on the 11th of July 1958. On the day of his execution Manuel seemed oblivious to his fate. Some of the papers relating to Manuel’s murder trial are restricted for seventy five years, until 2031.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.