Remember handwritten letters? Pretty much the only handwritten missives anyone gets today are birthday cards. But once upon a time, pen and paper were at technology’s bleeding edge. Together they created letters.

And a good letter is worth reading and re-reading.

Do you think more when you put pen to paper, wonder about its permanency and how that letter can be passed from hand to hand for judgement?

You can write and send an email quickly; or publish a tweet that if phrased badly leads to public humilation and a frenzied attack on your brain. You can get it right and see your words forwarded. But no-one wants to re-read them a day or a week later, never mind in a year or decades into the future. No-one has written the Great American Tweet.

But a letter can endure. You can touch and fold the paper, store the note in a box, screw it up, or tie it with ribbon. Everything about the letter has the power to speak and trigger a physical reaction.

Writing a good letter takes time.

In his 1876 book How To Write Letters, J. Willis Westlake, a professor at the State Normal School in Millersville, Pennsylvania, tutored us on the skill of writing a good letter:

A letter should be regarded not merely as a medium for the communication of intelligence, but also as a work of art. As beauty of words, tone, and manner adds a charm to speech, so elegance of materials, writing, and general appearance, enhances the pleasure bestowed by a letter…

Invention is the action of the mind that precedes writing. In all kinds of composition, there are two things necessary: first, to have something to say; second, to say it. Invention is finding something to say. It is the most difficult part of composition, as it is a purely intellectual process, requiring originality, talent, judgment, and information; while expression is to some extent a matter of mechanical detail, and subject to rules that can be easily understood and applied. A person can write out in a few weeks or months a work the invention of which requires the thought and labor of many years. Yet both parts of composition are equally essential. It is certainly a noble thing to have great thoughts, but without the power of expressing them the finest sentiments are unavailable.

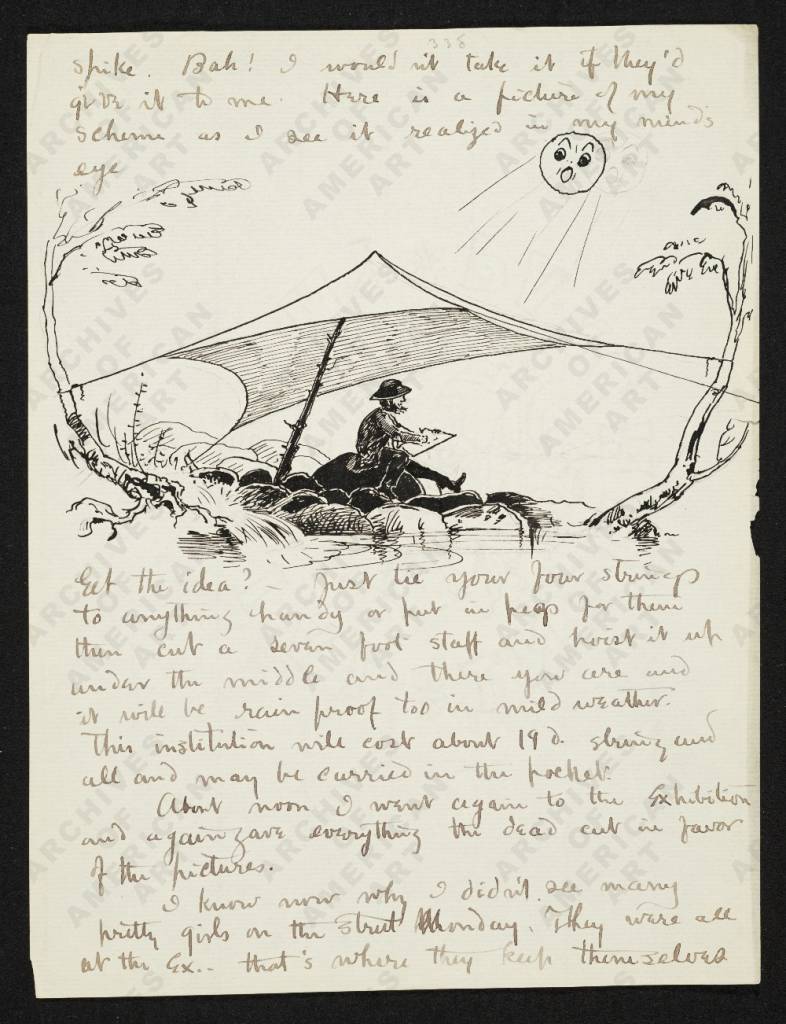

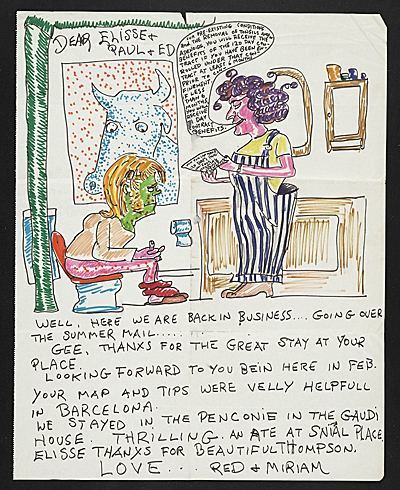

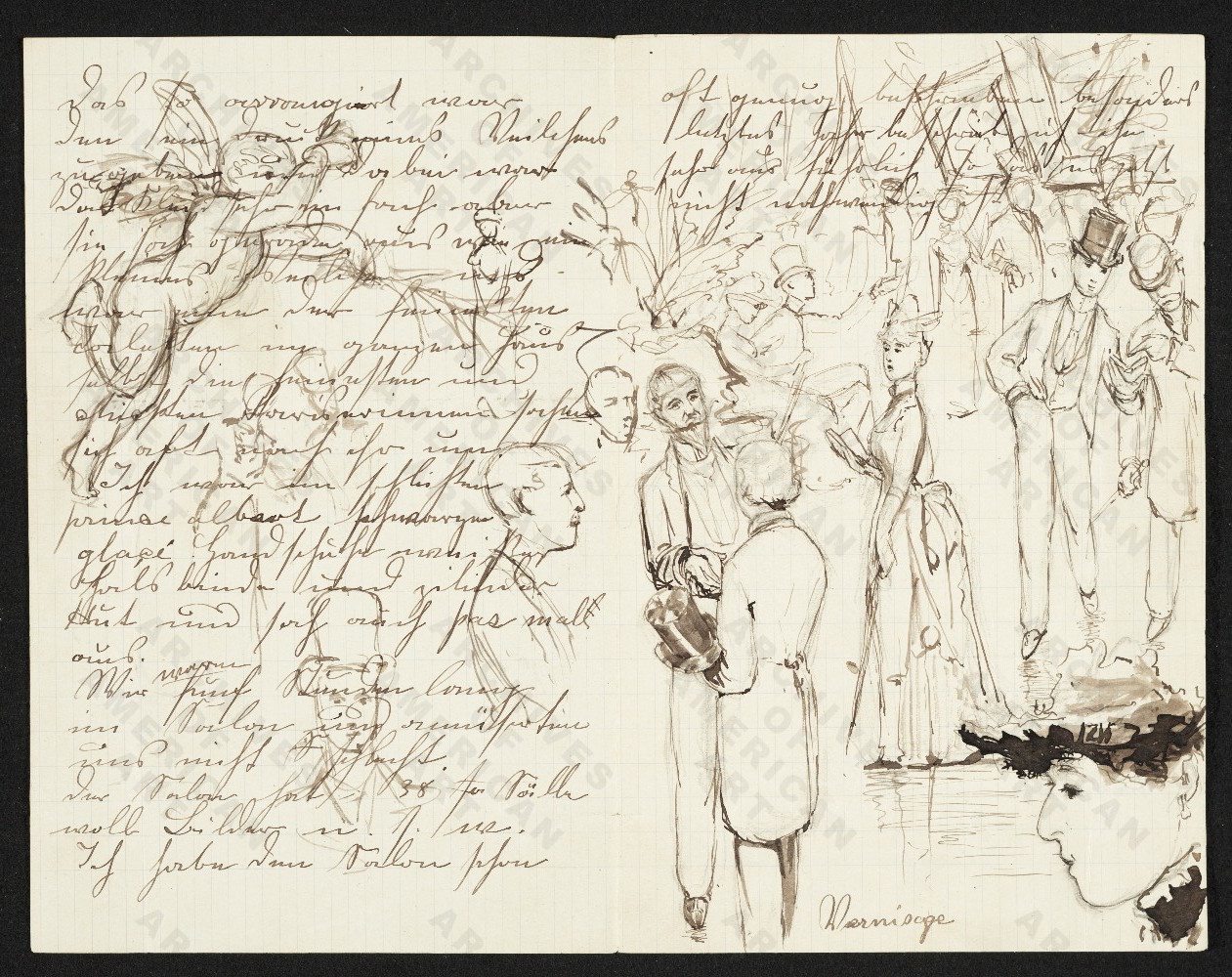

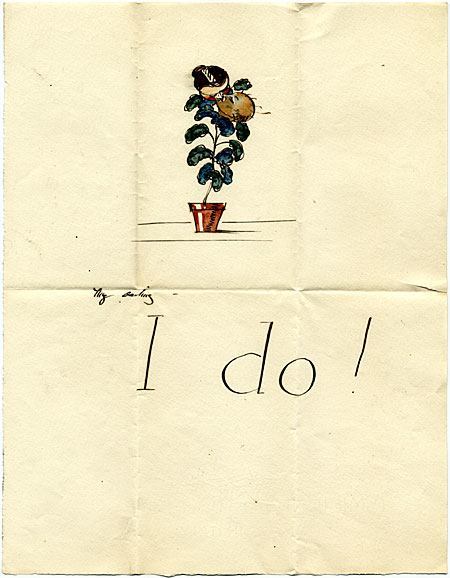

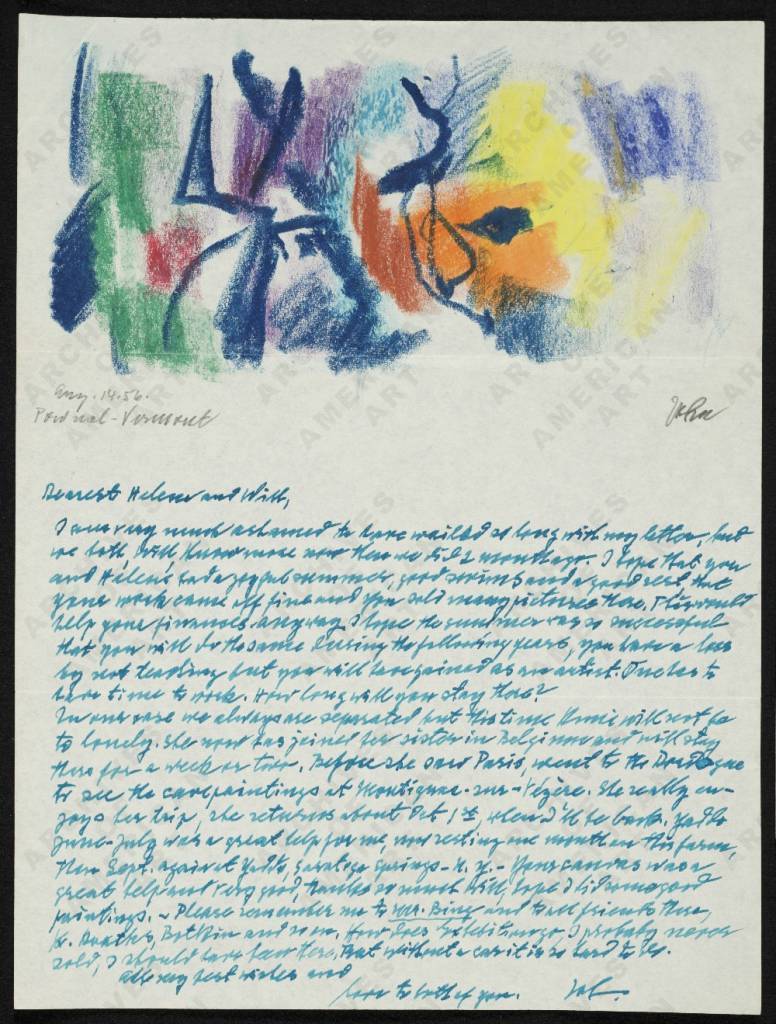

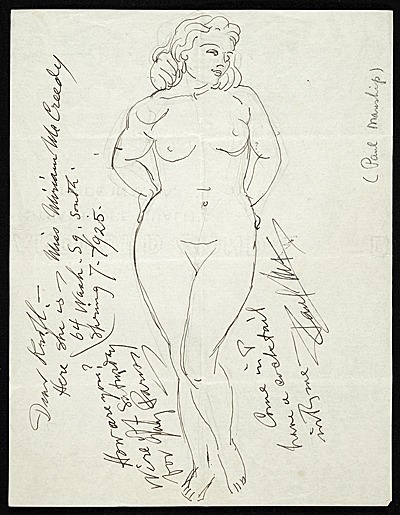

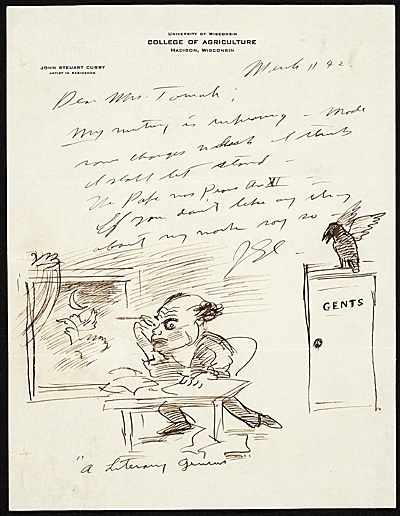

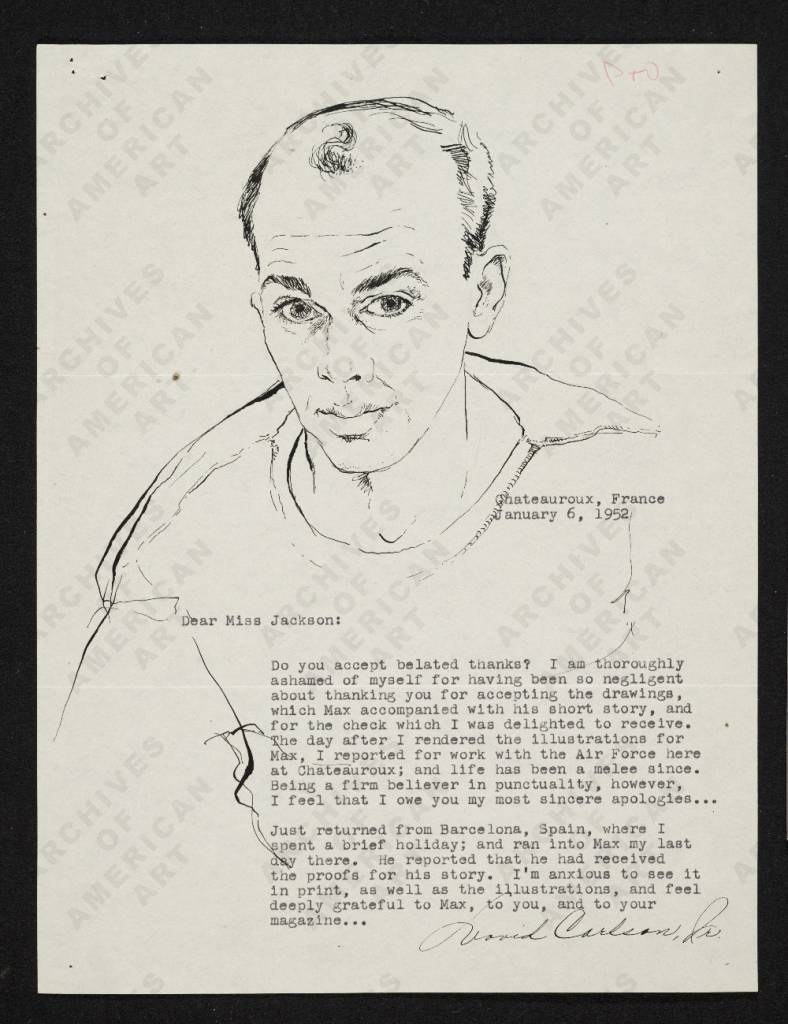

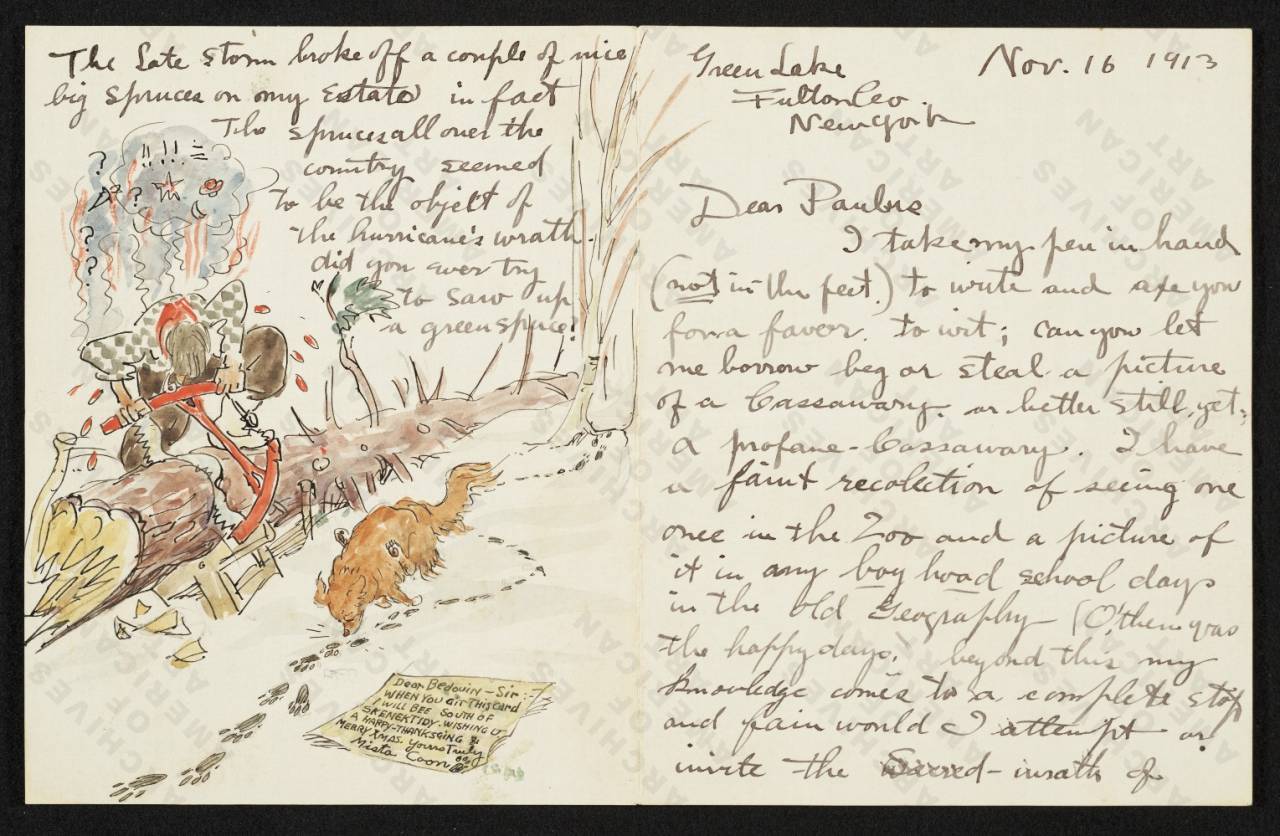

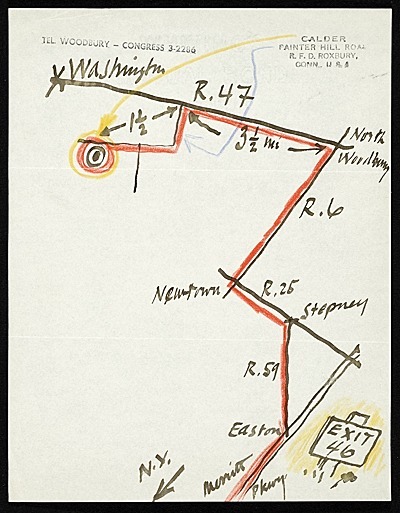

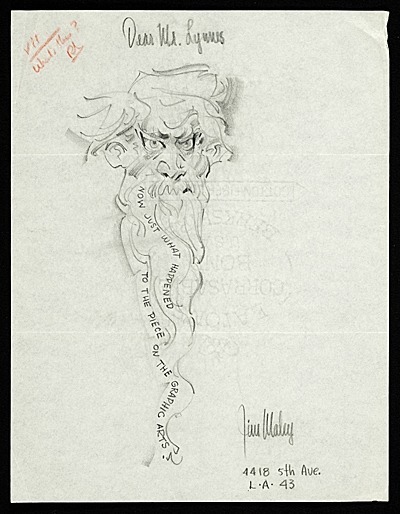

The Smithsonian’s archive of Illustrated Letters shows not only how letters endure but also how they offer an outlet for creativity, giving space for art, asides, random thoughts, after thoughts and doodles. The letters are from the 19th century to the late 1980’s. Graphologists who study mood and character through handwriting should enjoy these. The rest of us can try to work out what the words actually say.

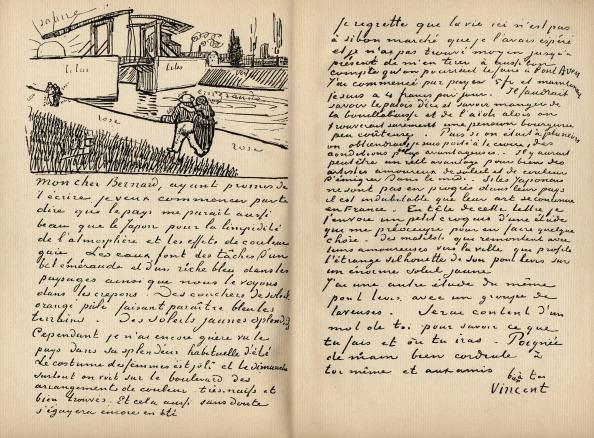

Facsimilie of letter from Vincent Van Gogh to Emile Bernard, Arles, 18 March 1888. Vincent Van Gogh, 1853-1890.

The letter should be a little more formal than the dialogue, since the latter imitates improvised conversation, while the former is written and sent as a kind of gift. . . . The letter should be strong in characterization. Everyone writes a letter in the virtual image of his own soul. In every other form of speech it is possible to see the writer’s character, but in none so clearly as in the letter – Demetrius

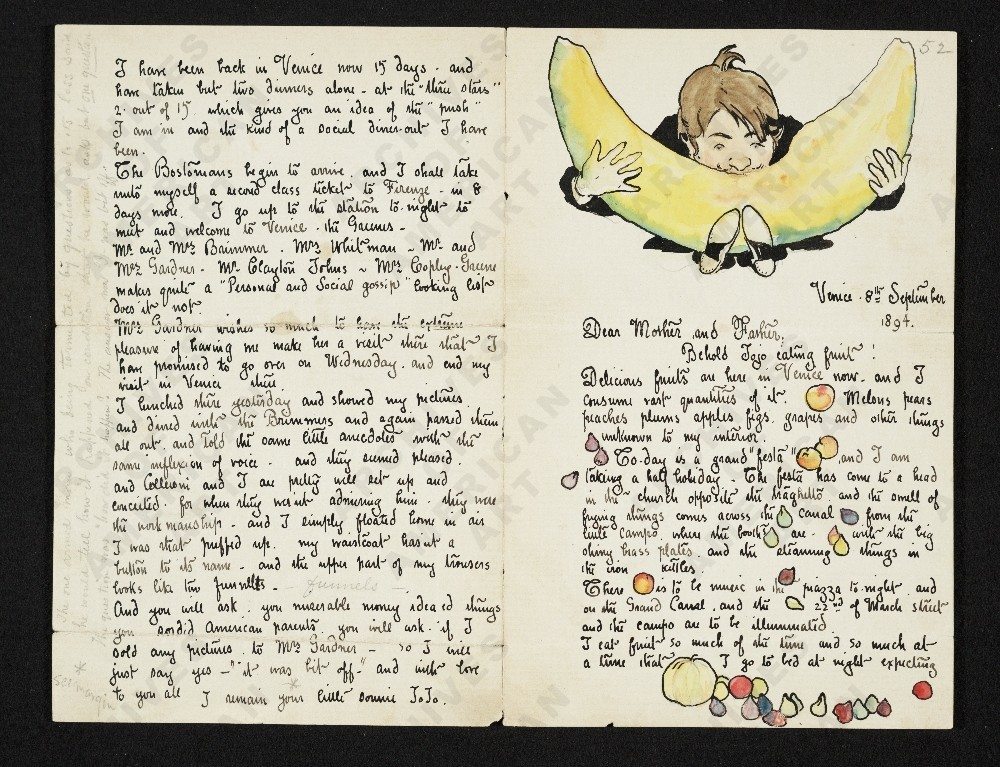

In this letter to his parents, painter Joseph Lindon Smith (1863-1950), illustrates the vast quantities of fruit he is consuming in Venice – *Melons, pears, peaches, plums, apples, figs, grapes, and other things unknown to my interior.* He also mentions the arrival of the “Bostonians,” his social events, and the sale of his pictures to Isabella Stewart Gardner, September 8, 1894. Joseph Linden Smith papers.

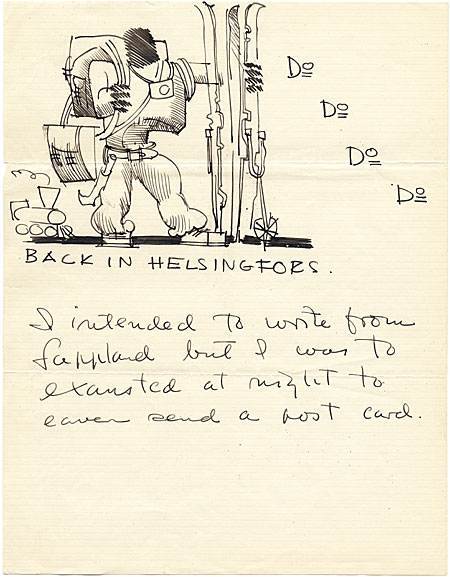

he papers of architect and interior designer Florence Knoll Bassett (b. 1917) include a series of illustrated letters from architect Eero Saarinen (1910−1961). In the mid-to-late 1930s, when this letter was written, she attended the Cranbrook Academy of Art, then the Architectural Association in London, and spent summers with the Saarinens. In an annotation among her papers she wrote: *Eero spend a year in Helsingfors working for an architectural firm. It is obvious from his illustrated letters that he preferred drawing to the written word. We all enjoyed the results.* Florence Knoll Bassett papers.

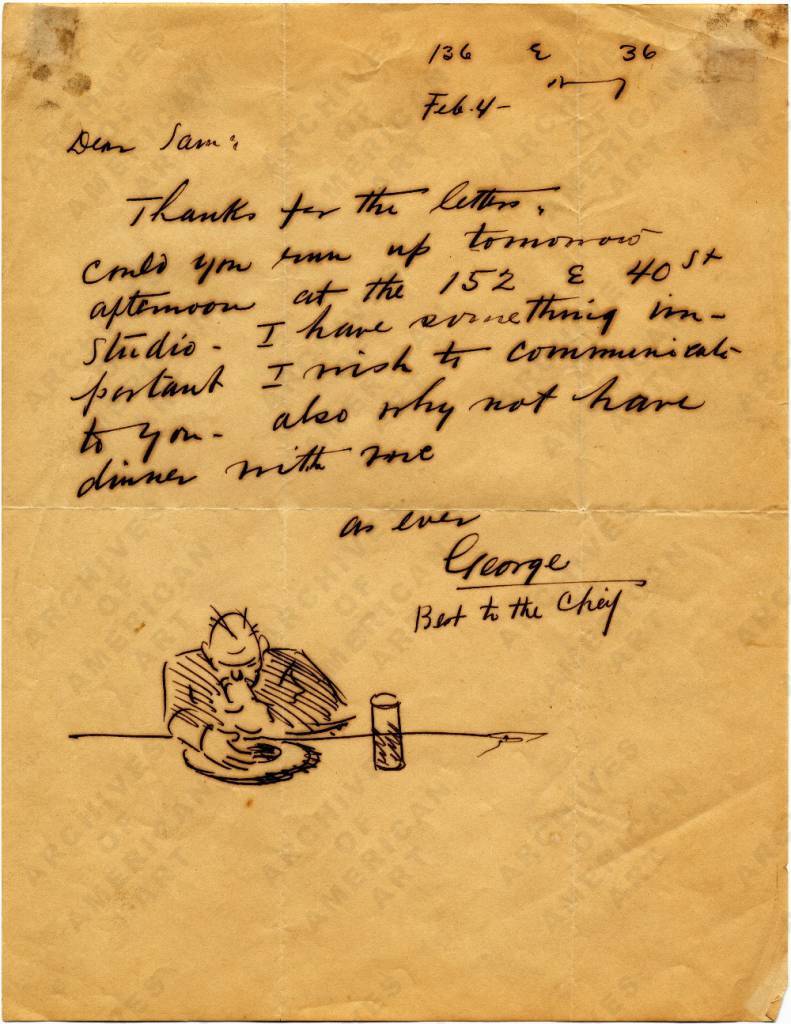

Letter from painter George Luks (1867–1933) to his friend lawyer and art dealer Samuel Ballin (1902–1985), February 4, 193-?.

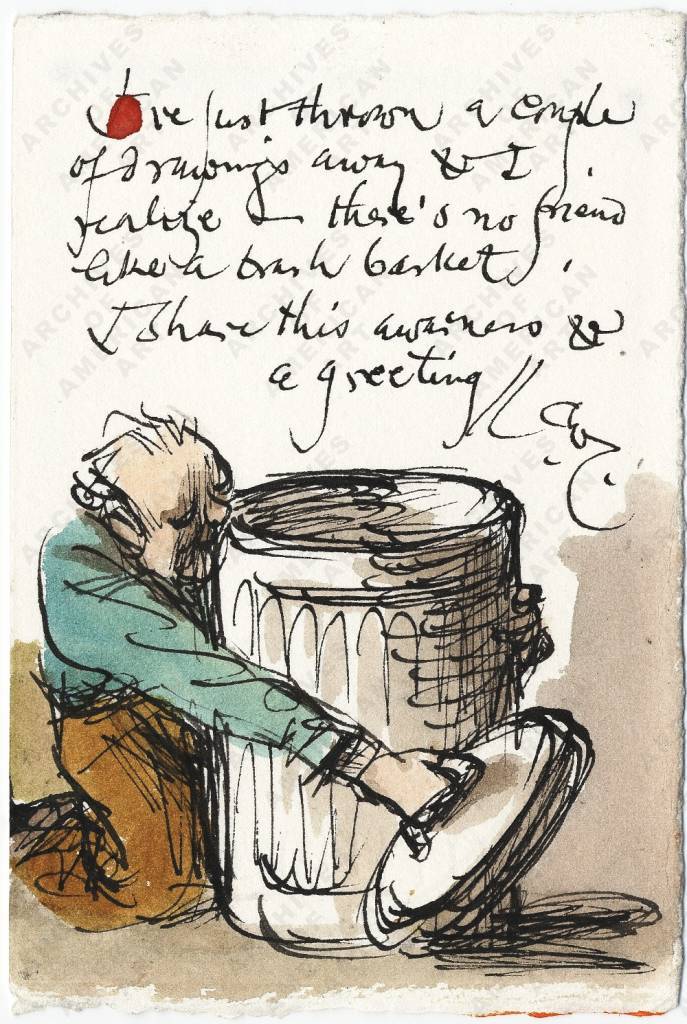

Warren Chappell (1904-1991) wrote to his friend Isabel Bishop (1902-1988),

“I’ve just thrown a couple of drawings away and I realize—there’s no friend like a trash basket.”

![Letter from Dorothea Tanning (b. 1910) to Joseph Cornell (1903–1972), March 3, 1948. In her autobiography Between Lives [Dorothea Tanning. New York: WW Norton and Co, 2001.] Tanning writes of her correspondence with Cornell, saying *I tried to decorate my letters his way* (90). Joseph Cornell papers.](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAA_cornjose_3163-709x1024.jpg)

Letter from Dorothea Tanning (b. 1910) to Joseph Cornell (1903–1972), March 3, 1948. In her autobiography Between Lives [Dorothea Tanning. New York: WW Norton and Co, 2001.] Tanning writes of her correspondence with Cornell, saying *I tried to decorate my letters his way* (90). Joseph Cornell papers.

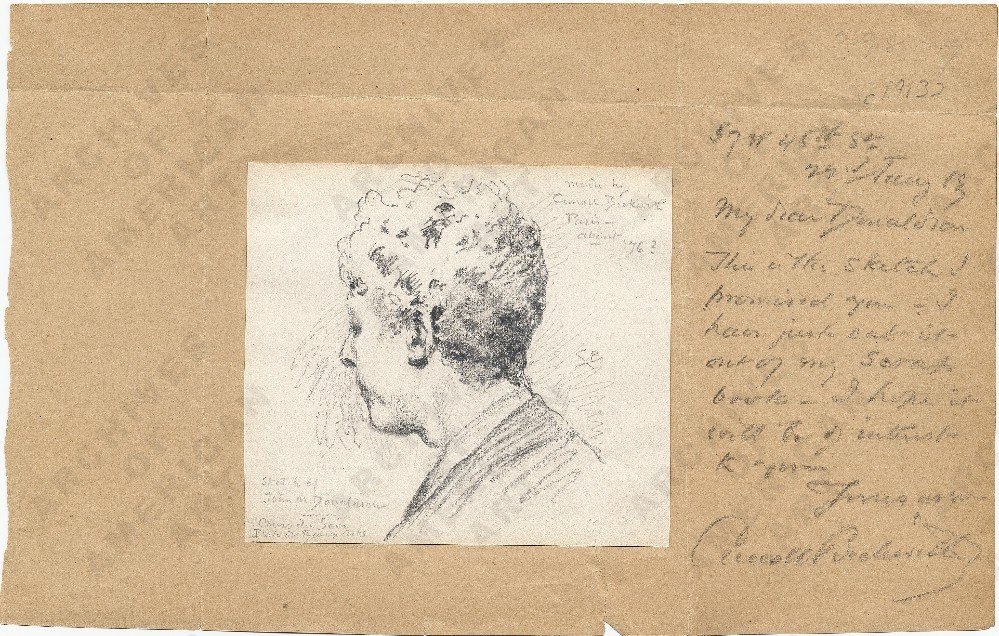

Letter from painter Carroll Beckwith (1852−1917) to architect John M. Donaldson (1854−1941) in which Beckwith affixes a pencil sketch he made of Donaldson while he was a student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, ca. 1876. John M. Donaldson papers.

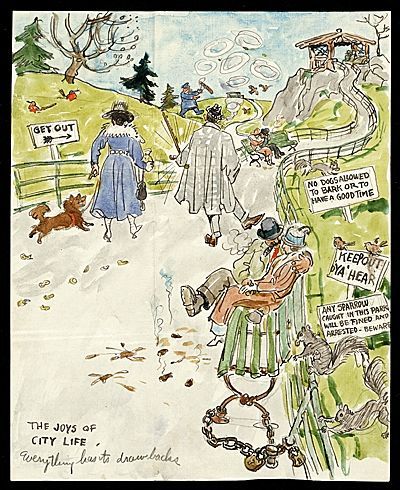

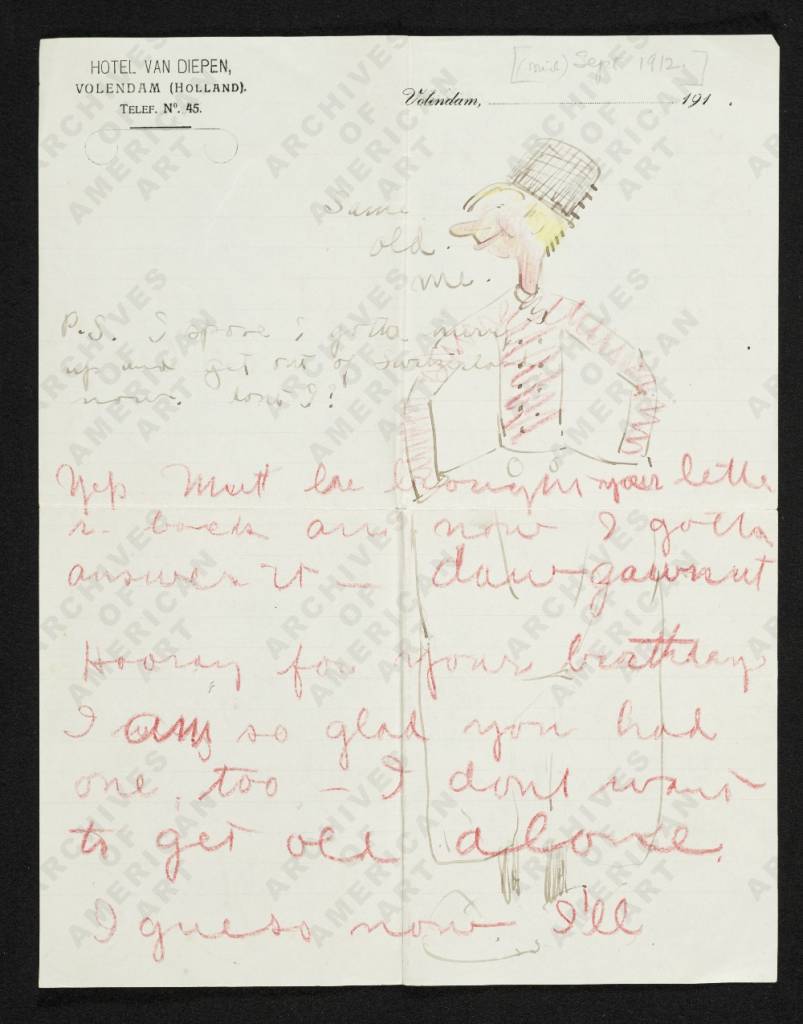

Alfred J. Frueh (1880−1968) was known for his caricatures of theater personalities. He drew cartoons and illustrated stories for The World, contributed a weekly drawing to Life magazine from 1920 to 1921, and his caricatures appeared in The New Yorker magazine from its first issue in 1925 until 1962. In this series of humorous letters to his fiancée Guiliette Fancuilli, he described his travels through Europe in 1912 and 1913, in each he pictures himself immersed in the culture and often in native costume. Frueh writes to Guiliette from Holland, ca. September 1912. Alfred J. Frueh papers.

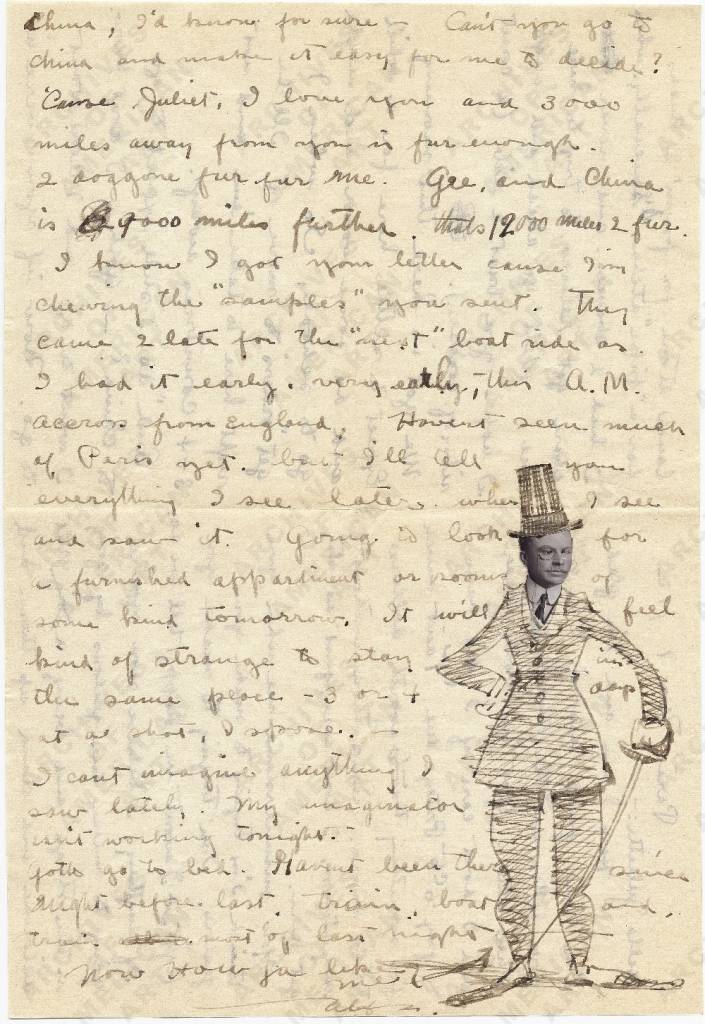

Alfred J. Frueh (1880−1968) was known for his caricatures of theater personalities. He drew cartoons and illustrated stories for The World, contributed a weekly drawing to Life magazine from 1920 to 1921, and his caricatures appeared in The New Yorker magazine from its first issue in 1925 until 1962. In this series of humorous letters to his fiancée Guiliette Fancuilli, he described his travels through Europe in 1912 and 1913, in each he pictures himself immersed in the culture and often in native costume. Frueh writes to Guiliette from Paris, November 7, 1912. Alfred J. Frueh papers.

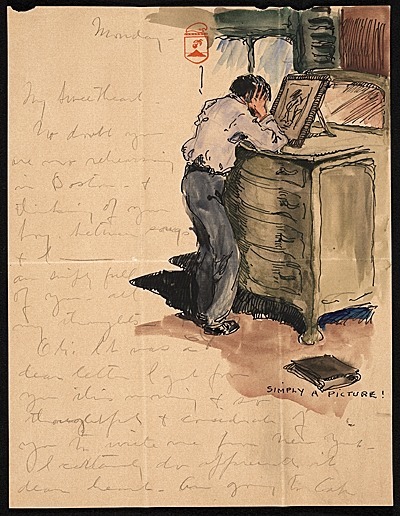

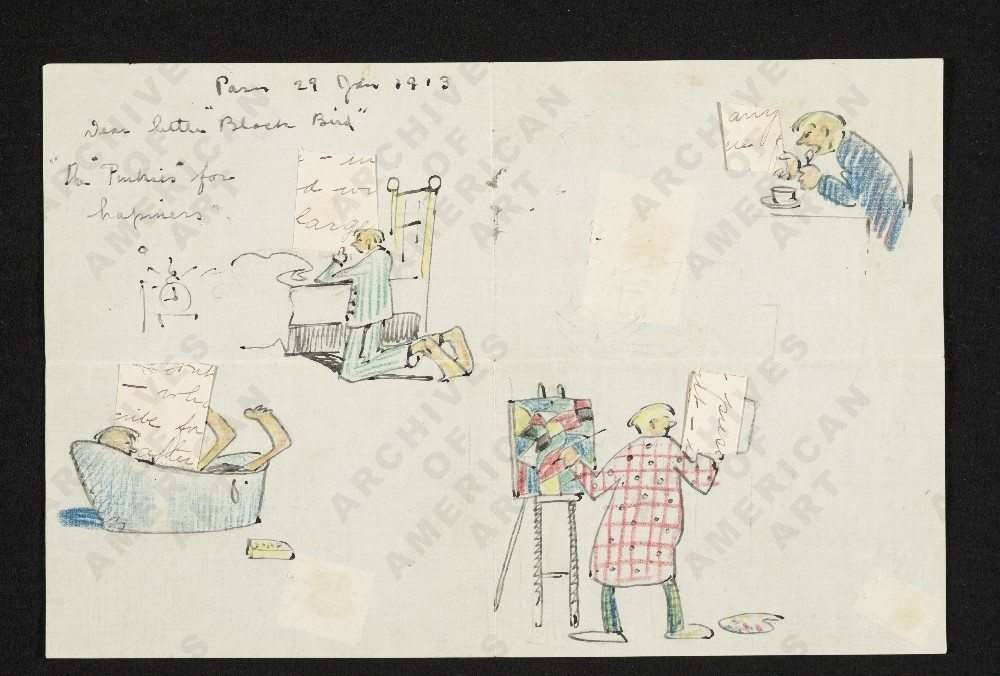

Alfred J. Frueh (1880-1968) was known for his caricatures of theater personalities. He drew cartoons and illustrated stories for The World, contributed a weekly drawing to Life magazine from 1920 to 1921, and his caricatures appeared in The New Yorker magazine from its first issue in 1925 until 1962. In this series of humorous letters to his fiancée Guiliette Fancuilli, he described his travels through Europe in 1912 and 1913, in each he pictures himself immersed in the culture and often in native costume. Frueh writes to Guiliette from Paris, January 29, 1913, showing how happily obsessed he is with her letters, which he calls “pinkies.” Alfred J. Frueh papers.

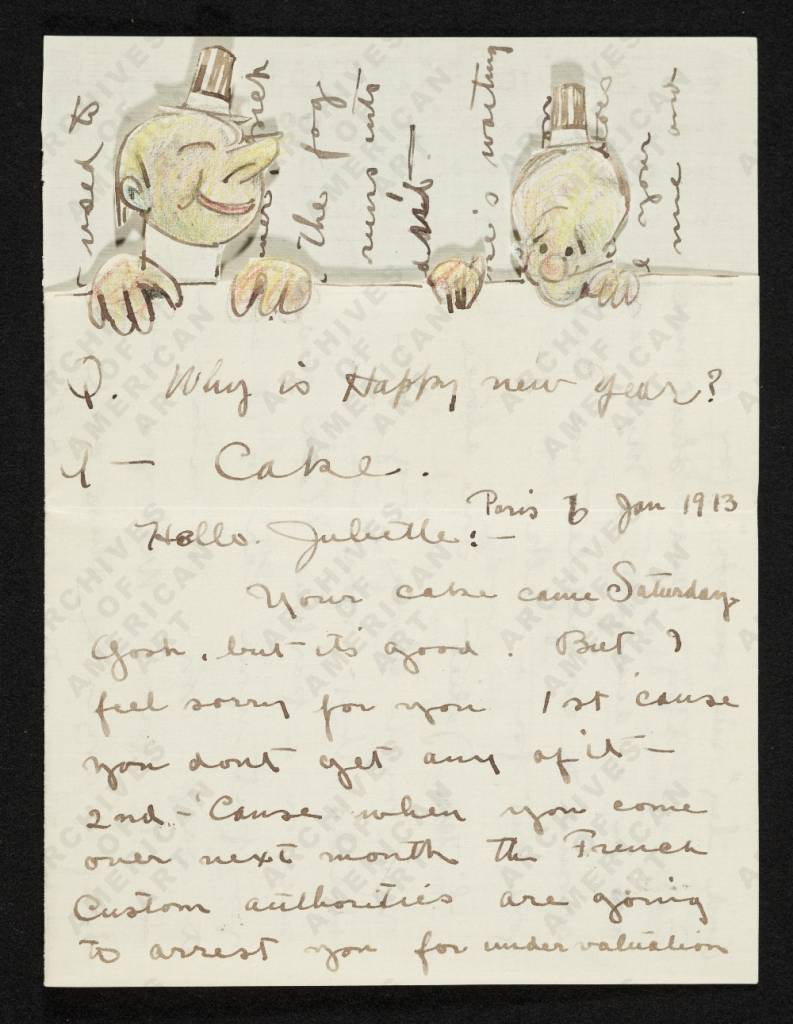

Alfred J. Frueh (1880-1968) was known for his caricatures of theater personalities. He drew cartoons and illustrated stories for The World, contributed a weekly drawing to Life magazine from 1920 to 1921, and his caricatures appeared in The New Yorker magazine from its first issue in 1925 until 1962. In this series of humorous letters to his fiancée Guiliette Fancuilli, he described his travels through Europe in 1912 and 1913, in each he pictures himself immersed in the culture and often in native costume. Frueh writes to Guiliette January 6, 1913. Alfred J. Frueh papers.

Alfred J. Frueh (1880−1968) was known for his caricatures of theater personalities. He drew cartoons and illustrated stories for The World, contributed a weekly drawing to Life magazine from 1920 to 1921, and his caricatures appeared in The New Yorker magazine from its first issue in 1925 until 1962. In this series of humorous letters to his fiancée Guiliette Fancuilli, he described his travels through Europe in 1912 and 1913, in each he pictures himself immersed in the culture and often in native costume. Frueh writes to Guiliette April 13, 1913. Alfred J. Frueh papers.

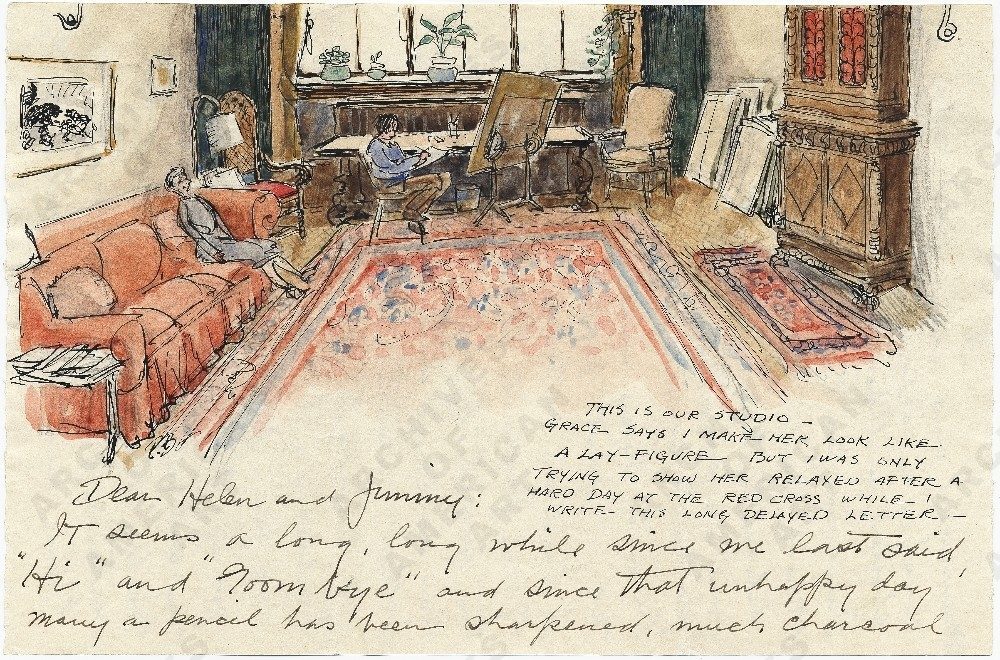

Letter from illustrator Paul Bransom (1885−1979) to Helen and Jimmy Hays. In the 1920s, the Bransoms built a home and studio at Canada Lake in the Adirondacks, where they were part of a small summer colony of artist and writers including Helen Hays, Clare Dwiggins, his daughter Phoebe Dwiggins, Todhunter Ballard, Charles Sarka, Margaret Widdemer, Mabel Cleland, Herbert Asbury, Emily Hahn, and James Thurber. In this 1943 letter Bransom paints his home studio. Helen I. Hays papers.

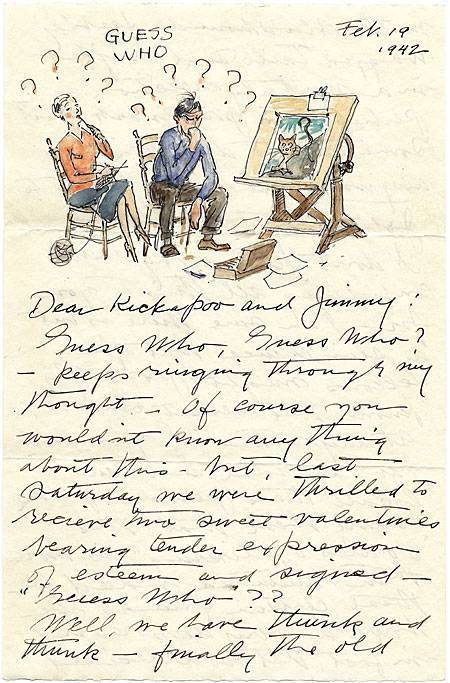

Letter from illustrator Paul Bransom (1885-1979) to Helen and Jimmy Hays. In the 1920s, the Bransoms built a home and studio at Canada Lake in the Adirondacks, where they were part of a small summer colony of artist and writers including Helen Hays, Clare Dwiggins, his daughter Phoebe Dwiggins, Todhunter Ballard, Charles Sarka, Margaret Widdemer, Mabel Cleland, Herbert Asbury, Emily Hahn, and James Thurber. In a letter dated February 19, 1942, Bransom dreams of their summer vacation home. Helen I. Hays papers.

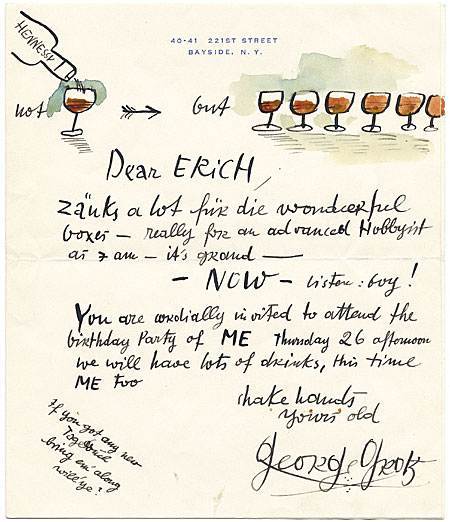

Letter from painter and printmaker George Grosz (1893−1959) inviting his friend Erich S. Herrmann to his birthday party, undated. Erich S. Herrmann papers.

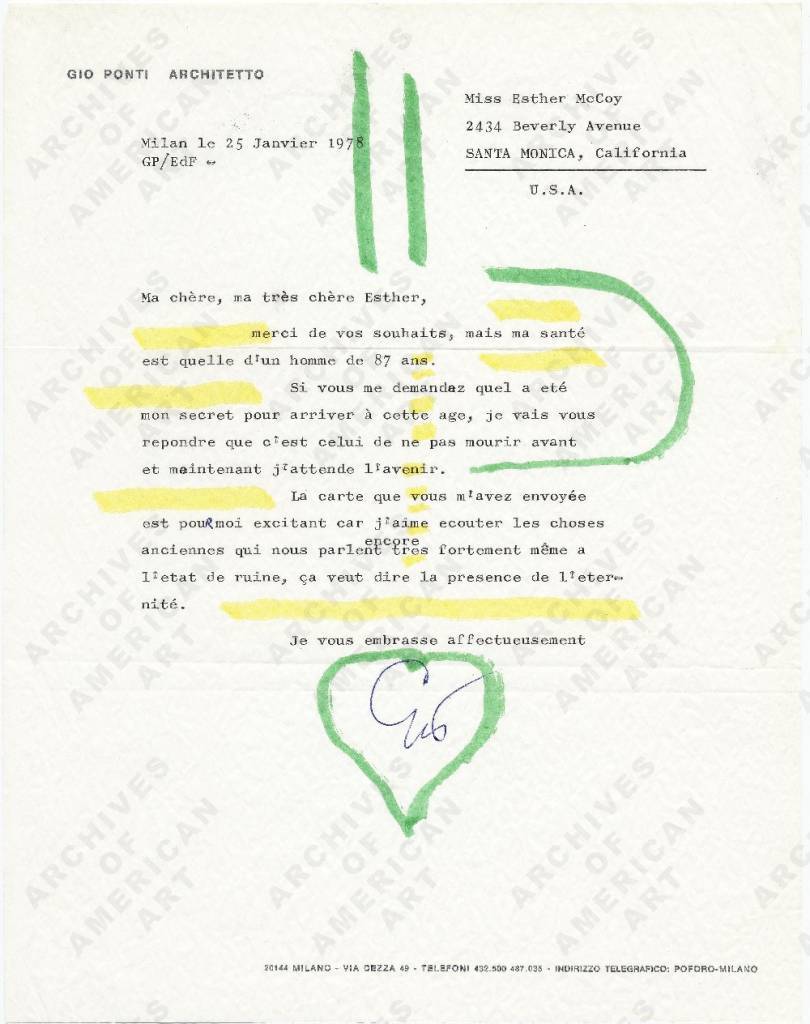

The papers of architectural historian Esther McCoy (1904−1989) include a series of affectionate illustrated letters from Italian architect and designer Gio Ponti (1891−1979). Ponti’s concept of total design extended to these fanciful communications from 1968 and 1978. Esther McCoy papers.

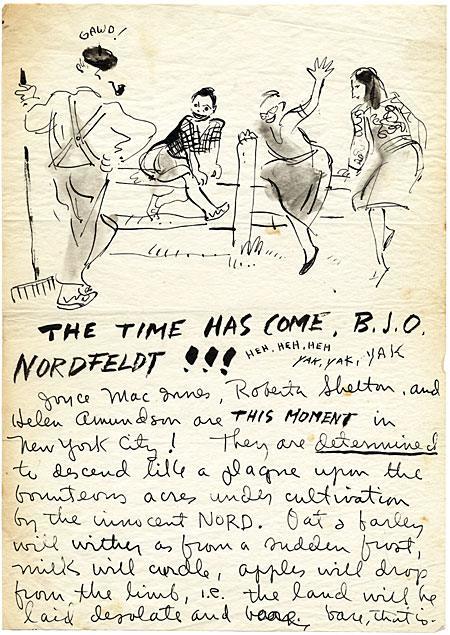

Letter from former student Roberta Shelton to Bror Julius Olsson (B.J.O.) Nordfeldt (1878–1955), ca. 1946. Nordfeldt taught Skoog at the Minneapolis School of Art in 1944. This letter is a request from Shelton and her fellow classmates to visit Nordfeldt on his farm in New Jersey while they are visiting New York: *Let me state that we wish quite desperately to see you, that at the slightest bidding, we will come tearing down to Lambertville (wherever that may be) and attempt for a couple hours to conduct ourselves in dignified and unobtrusive style.* Nordfeldt was a popular teacher, well liked by his students. Bror Julius Olsson (B.J.O.) Nordfeldt papers.

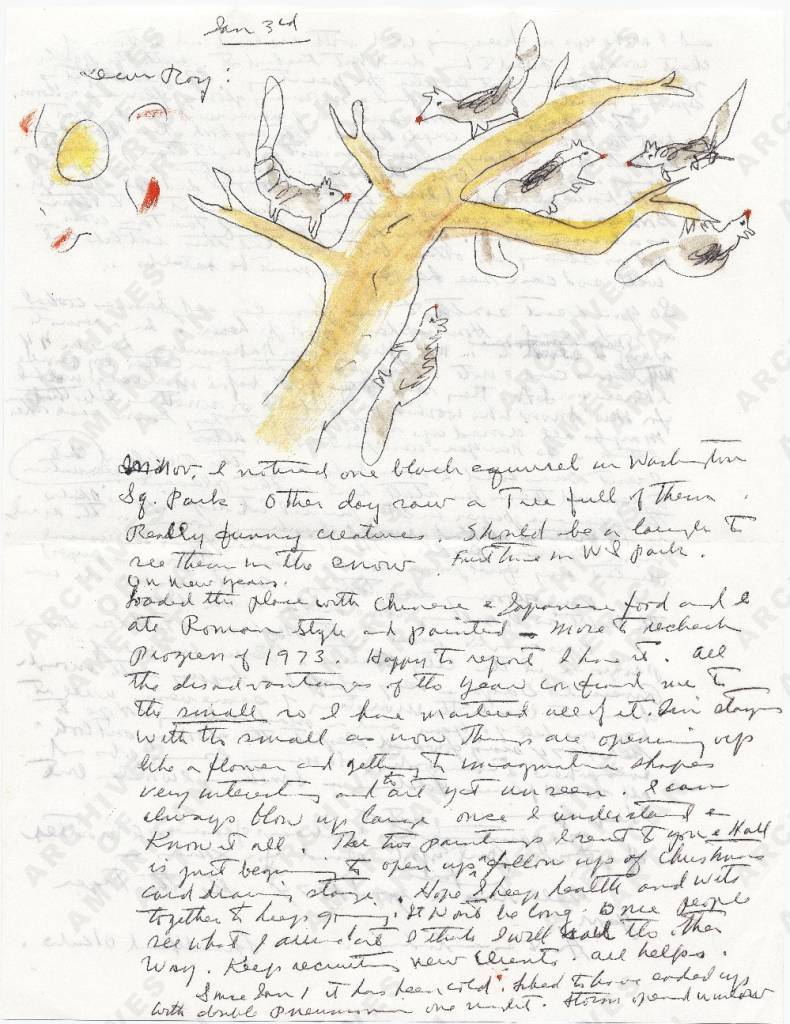

Painter Miné Okubo (1912−2001) is best known for her book Citizen 13660, a memoir of her experience as a Japanese American detained at the Tanforan Assembly Center south of San Francisco, and then the relocation center at Topaz, Utah. After January 1944, she settled in Greenwich Village and continued to paint until her death in 2001. These three letters are part of Okubo’s illustrated correspondence with collectors Roy Leeper and Gaylord Hall in the early 1970s. Okubo to Leeper January 3, 1974.

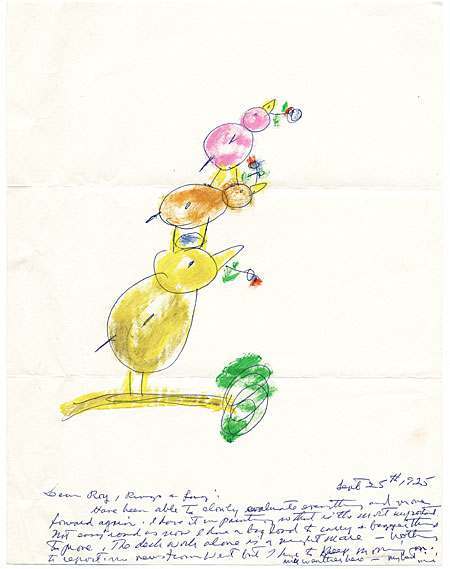

Painter Miné Okubo (1912−2001) is best known for her book Citizen 13660, a memoir of her experience as a Japanese American detained at the Tanforan Assembly Center south of San Francisco, and then the relocation center at Topaz, Utah. After January 1944, she settled in Greenwich Village and continued to paint until her death in 2001. These three letters are part of Okubo’s illustrated correspondence with collectors Roy Leeper and Gaylord Hall in the early 1970s. Okubo to Leeper September 25, 1973.

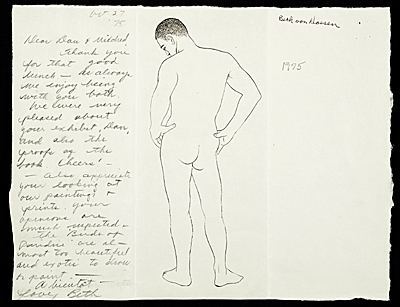

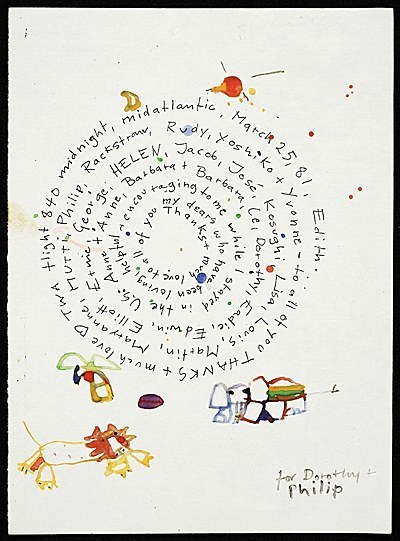

Letter from painter, writer and critic Edith Schloss to Philip Pearlstein (b. 1924), March 25, 1981. On the verso of the thank-you note, Schloss writes: *I wish we had a national archives here to give all my junk and diaries to—I’m not good a throwing away things.* During Schloss’s stay in New York, Pearlstein may have mentioned the Archives of American Art as an appropriate repository. He donated his papers to the Archives in installments from 1975 to 1999. Schloss later donated her papers to the Archives as well. Philip Pearlstein papers.

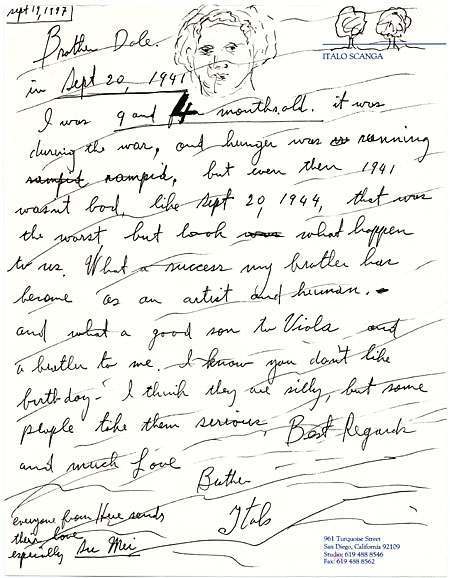

Letter from Italo Scanga (1932–2001) to artist Dale Chihuly (b. 1941), September 19, 1997. This letter is birthday greetings from Scanga to Chihuly. Scanga describes his circumstances on September 20, 1941, the day Chihuly was born. Italo Scanga papers.

Painter Joseph Lindon Smith (1863-1950) penned a note to his parents about his arrival in Dublin, sketching himself as an overloaded traveler. Joseph Lindon Smith papers.

Painter Moses Soyer (1899-1974) sent what he called a “puzzle picture” to his son David, who was away at a camp in the Catskills in the summer of 1940. In a watercolor vignette, he pictures the family dog and cat, Tinkerbell and Jester, along with the words “Where is Jester” (the answer is, hiding under the dog).

Soyer also prominently features baseball great Dizzy Dean, who was about to make a comeback in the minor league. He mentions that the Cincinnati Reds are in the lead. (They would win the World Series that year.) The baseball banter carries over to the margin, where Soyer sends a glove flying from their home at 432 West Street in New York to David’s bunk at Camp Quannacut.

![Letter from Gaston Longchamp to Marguerite [Stix] and Co., describing a birthday dinner for his dog Zoto, and picturing the artist seated at a table with Zoto, two nude women, and a pig about to feast on a *sole Normande,* ca. 1955. In 1955, Longchamp was involved in the Artist Gallery 20th Anniversary Show, which Hugh Stix (Marguerite’s husband) curated. Hugh Stix papers.](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAA_stixhugh_3176-783x1024.jpg)

Letter from Gaston Longchamp to Marguerite [Stix] and Co., describing a birthday dinner for his dog Zoto, and picturing the artist seated at a table with Zoto, two nude women, and a pig about to feast on a *sole Normande,* ca. 1955. In 1955, Longchamp was involved in the Artist Gallery 20th Anniversary Show, which Hugh Stix (Marguerite’s husband) curated. Hugh Stix papers.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.