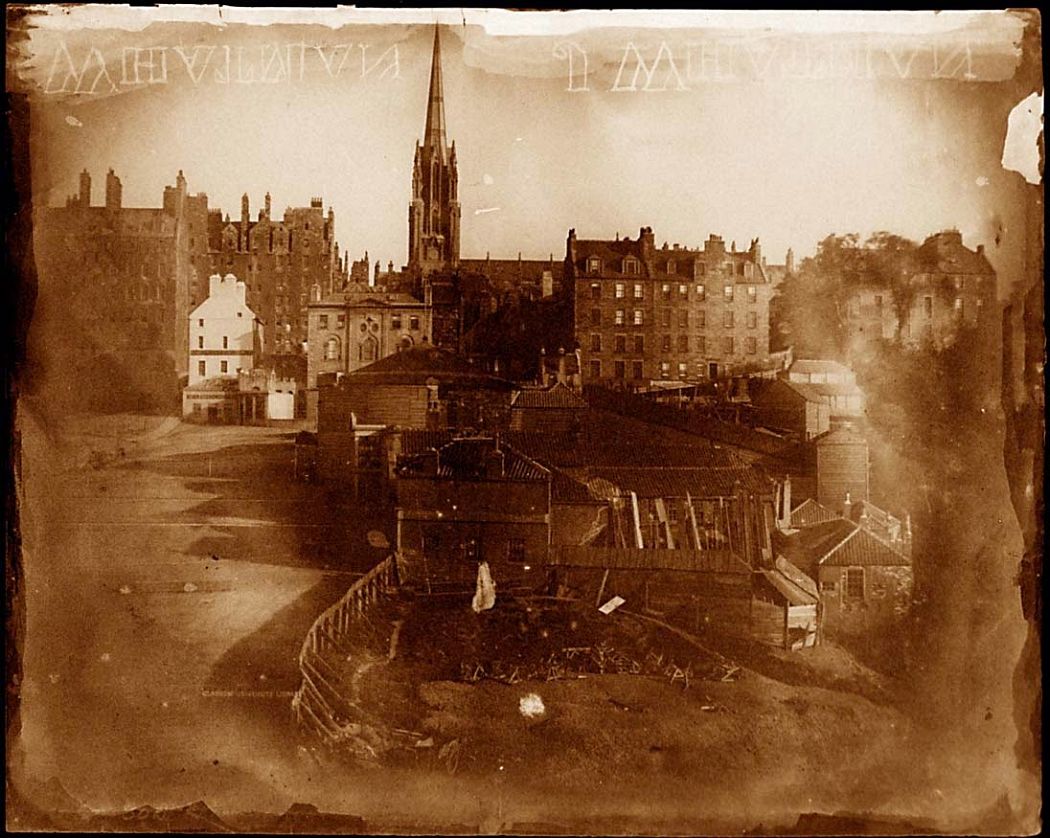

View of the Mound, 1843. Inverted negative–the writing in the sky is a watermark in the paper, made visible by the process of negative scanning.

In the history of photography, the name Louis Daguerre is well-known, as is that, to a lesser extent, of his onetime partner, French scientist Joseph Nicephor Niepce, credited with taking first photograph in 1826, an eight-hour exposure he called the “heliograph.” As with every new technology, from the camera to the computer, many inventors vied to perfect their processes and corner the market in the ensuing years.

In the U.S., Hamilton Smith worked with iron instead of copper, a method he patented in 1856 but which did not catch on. Five years earlier, English sculptor Frederick Scoff Archer invented the wet-plate negative, an effective process for developing multiple prints of an image, something that could not be done with the otherwise extremely popular daguerreotype.

But even before these unique solutions, another English inventor, the polymath and politician Henry Talbot Fox, devised a method for making multiple prints that also produced some of the most compellingly beautiful images in the early history of the medium. Indeed, in 1841, when Talbot patented his process, he named it the “calotype,” from the Greek kalos, meaning “beautiful.”

Requiring an exposure of “mere seconds,” writes the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Malcolm Daniel, the technique, while unstable and unpredictable, “opened up a whole new world of possible subjects for photography,” including the first known photograph at the pub, an image of three grinning gentlemen, among them one of the photographers, David Octavius Hill.

A view of the Old Town

Hill and his partner Robert Adamson worked primarily in Edinburgh and became well-known for their attractive calotypes. Talbot’s patent did not apply in Scotland, and he encouraged photographers there to experiment with his methods and corresponded with Adamson’s brother, a professor of chemistry and curator of the College Museum.

Hill and Adamson, writes Daniel, made “a perfect team.” The former, a landscape painter, “had important connections in artistic and social circles in Edinburgh” and “easily attracted a distinguished clientele.” The latter, twenty years younger than his partner, “was a consummate technician, excelling in—and even improving upon—the various optical and chemical procedures developed by Talbot.”

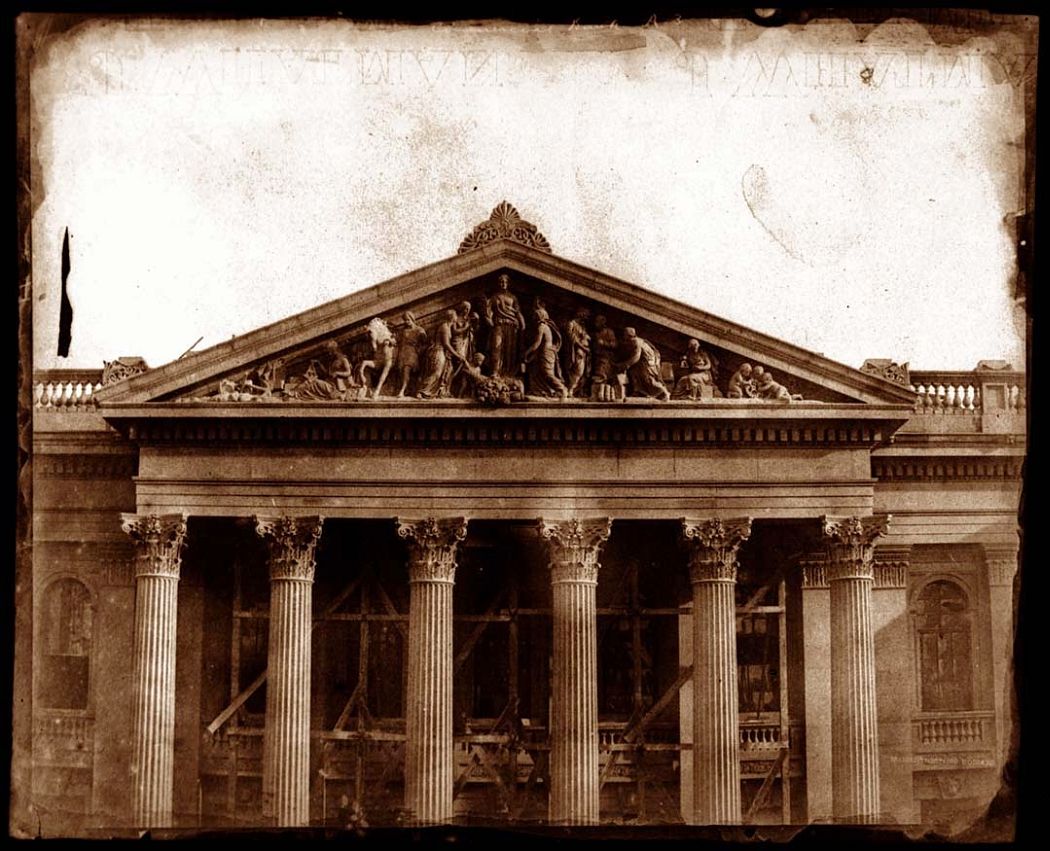

They made their reputation as portraitists, their work compared by painter John Harden to “Rembrandt’s but improved.” Unlike tintype processes, the calotype used a paper negative, which could then be printed on salted paper. The sepia-toned results tended to have a high contrast and a diffuse graininess that lend them a painterly quality.

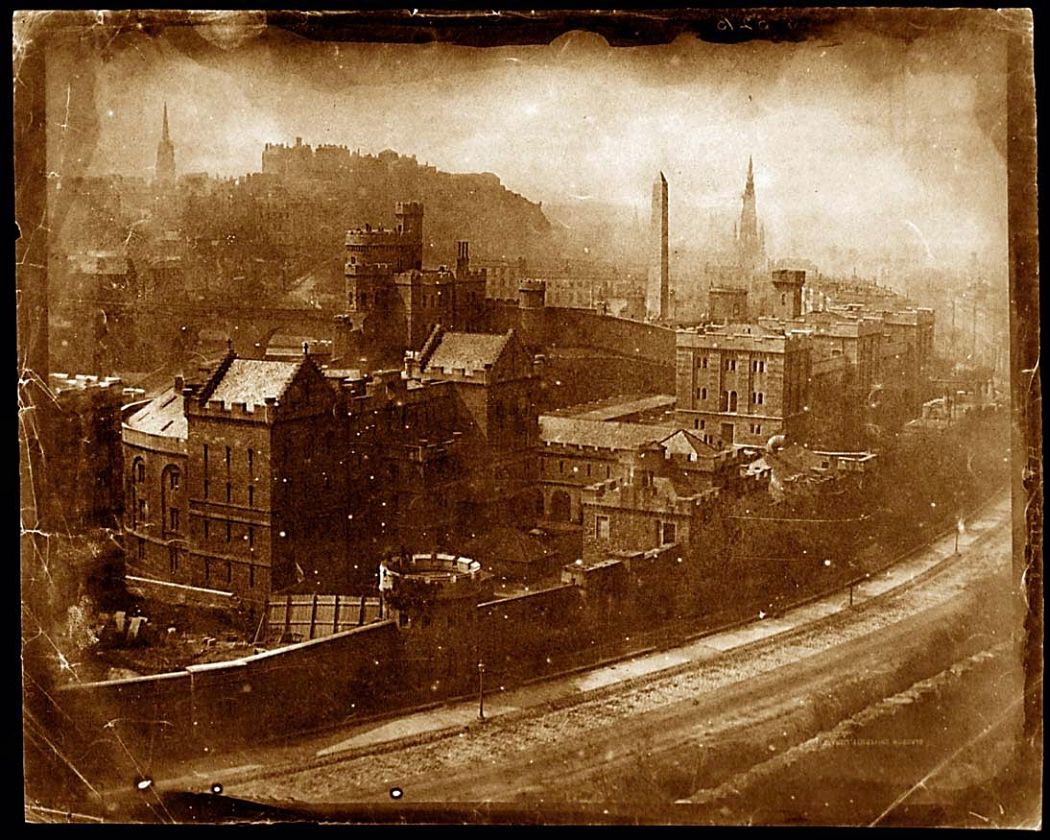

Hill and Adamson used their skill to not only capture images of the local worthies but to photograph Adamson’s hometown of St. Andrews and document Edinburgh in the images you see here from 1843-4, some of the earliest views of the city and some of the most beautifully preserved calotype cityscapes from the period.

via Monovisions

View from Calton Hill

The National Commercial Bank, George Street

View of the New Town from Calton Hill

The Old Town, 1843

View from Calton Hill

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.