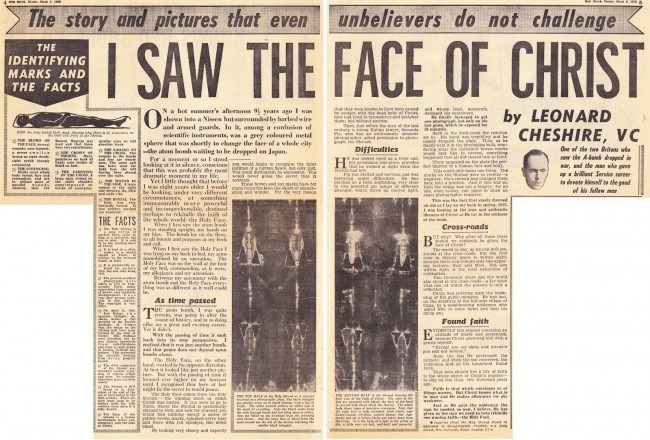

ON March 7th 1955, the Daily Sketch asked: “Is This The World’s Greatest Picture?” Readers gazed upon a photo of the Turin Shoud, the burial cloth of Jesus – showing his face and body after the crucifixion. Well, so they said.

Leonard Cheshire VC told reades that he had seen the face of Christ:

The Turin Shroud is most likely a medieval forgery. Probably. In 1988, Oxford University said the cloth was 728 years old. The University of Padua said it was made between 300BC and AD400.

But…

…a new study claims than an earthquake in Jerusalem in 33AD may have not only created the image but may also have skewed the dating results. The Italian team believes the powerful magnitude 8.2 earthquake would have been strong enough to release neutron particles from crushed rock. This flood of neutrons may have imprinted an X-ray-like image onto the linen burial cloth, say the researches.

In addition, the radiation emissions would have increased the level of carbon-14 isotopes in the Shroud, which would make it appear younger.

But what of the witness, Leonard Cheshire, was he credible?

Group-Captain Leonard Cheshire, VC, triple DSO and DFC, pictured as he boarded an Air India liner at London Airport. He is going to launch his new home for the chronic sick recently established in the hills at Kodaikanal, Southern India. He will be seeing it for the first time. Date: 02/11/1955

Music fans might know the name from Pink Floyd’s The Wall Live in Berlin concert of July 21 1990. Leonard Cheshire opened the concert by blowing a World War II whistle (via Open Culture).

The Roger Waters website explains:

72 year old Leonard Cheshire, a former pilot of the British Air Force, had been an official British observer, and was an official eyewitness to the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki in 1945. Mr. Cheshire, now an activist against war, decided to create a living memorial to all the people who had lost their lives in war in the last 100 years. With this aim a charity fund was organized, and on the 1st of September 1989, on the 50th anniversary of commencement of the second World War, the fund was established and it received huge international support. Cheshire’s idea was very simple – to collect five pounds sterling for each life lost in all wars of the last 100 years, and thus to base the fund on 500,000 million pounds. The base would always remain untouched in honor of those 100,000 million dead, but the dividends earned on this sum would be used to offer assistance to the victims of future catastrophes and natural disasters (floods, famine, earthquakes etc.), such that the capital would be offered only if other sources were unable to meet the demands. Those adversities which go unrecognized by others will find help with us – said the founder of The Memorial Fund for Disaster Relief.

Arriving at St Paul’s Cathedral in London to attend a service of Thanksgiving for the life of Sir Barnes Wallis, inventor of the bouncing bomb used by the Dam Busters in the Second World War, are Eve Gibson, wife of the late Wing Commander Guy Gibson, leader of the Dam Busters 617 squadron and former ace wartime bomber pilot Group Captain Leonard Cheshire.

Date: 27/02/1980

The Independent:

Cheshire was the son of the eminent Oxford lawyer Professor Geoffrey Cheshire; but neither at Stowe nor at Oxford did he prove a particularly bright or industrious student. In an extrovert generation, he was the most extrovert. Intentionally or unintentionally, he always seemed to attract the headlines (he held the record from Hyde Park Corner to Magdalen Bridge in an Alfa Romeo, for which he could not pay). Ironically, in view of his later life he avowedly modelled himself, on Leslie Charteris’s ‘The Saint’.

But he did join the Oxford University Air Squadron and became a competent though not brilliant pilot. And, unusally among his contemporaries, he foresaw the coming of the Second World War. In the summer of 1939 he took a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force and was posted to Hullavington to complete his training (typically, when still not fully trained, he volunteered for the Russo-Finnish War) Perhaps to his disappointment, he was posted to Bomber Command.

Leaving St Paul’s Cathedral in London after a service of Thanksgiving for the Life of Sir Barnes Wallis, inventor of the bouncing bomb used by the Dambusters squadron during the Second World War, are former ace wartime bomber pilot Group Captain Leonard Cheshire (foreground, left) and Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett (centre), who led the Pathfinder Force, with other members of the Pathfinder Association.

Date: 27/02/1980

He died in 1992. The New York Times wrote:

G. Leonard Cheshire, who was Britain’s most decorated pilot in World War II but whose distress over the destruction of war moved him to found an international network of homes for sick people, died Friday in London. He was 74 years old.

He died of motoneuron disease, a family spokeswoman said.

During the war, he flew more than 100 bombing missions over Germany and commanded the No. 617 Squadron, known as the Dambusters for their destruction of vital German dams. His ranks included wing commander and group captain. His combat exploits won many decorations, including the Victoria Cross, the nation’s highest military honor.

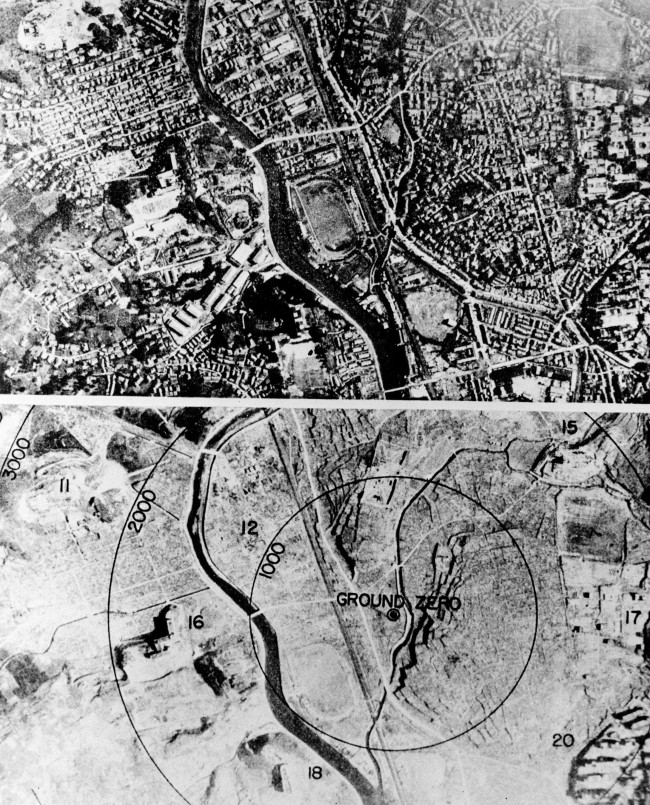

He was also the Royal Air Force’s official observer of America’s atomic bombing of Nagasaki — an experience that he said affected him so deeply that he committed himself to help others.

Group Captain Leonard Cheshire was Britain’s official observer of the bombing and had watched it from the air.

Cheshire believed that it brought a merciful end to the war with far less death and suffering than would otherwise have been the case. Many survivors refsued to meet with him at later memorial event.

His views were not isolated.

In this eye witness account of the Nagasaki bomb, William L. Laurence, Science writer for the New York Times, and Special Consultant to the Manhattan Engineer District and former Pulitzer Prize winner, opines:

Does one feel any pity or compassion for the poor devils about to die? Not when one thinks of Pearl Harbor and of the death march on Bataan.

About 30% of Nagasaki, including almost all the industrial district was destroyed by the bomb and nearly 74,000 were killed and a similar number injured. Residents of both cities are still suffering the physical and mental consequences of radiation to this day.

On 14 August – five days after the bomb – Japan surrendered to the Allies.

Cheshire later recalled the cloud caused by the atomic blast in Martin Gilbert’s Second World War: “Obscene in its greedy clawing at the earth, swelling as if with its regurgitation of all the life that it had consumed.”

The obituary continues:

After the war, he worked with homeless veterans but suffered from burn-out and went to Canada, where he worked variously as an undertaker, delivery man and firewood cutter.

Returning to England, he found his veterans’ organization collapsed by debt. While casting about for his mission in life, he heard about a veteran dying of cancer. He took the man in and nursed him through his illness.

Then other impoverished patients began showing up. Donated supplies and money trickled in, and volunteer nurses and doctors joined the cause.

Eventually those efforts grew into the Cheshire Foundation Homes, which now house disabled people in 50 nations.

In 1981, Queen Elizabeth appointed him to the Order of Merit, and last year he was made a life peer in the House of Lords. Prime Minister John Major praised him as a national hero for his war record and civilian contributions.

Lord Cheshire was previously married to Constance Binney, an American actress. His survivors include his wife, Baroness Sue Ryder of Warsaw, a son and a daughter.

Sue Ryder is, of course, known for her charity work.

Both Ryder and Cheshire featured on episodes of This Is Your Life:

Sue Ryder and her and Leonard Cheshire’s two children Elizabeth and Jeromy, at the Polish Embassy in Portland Place, London, where she was presented the Order of Polonia Restituta Officer’s Cross, awarded by the Council of State of the Polish People’s Republic. Polish Ambassador Jerzy Morawski is seen talking to Elizabeth, who is in traditional Polish costume.

Date: 25/11/1965

Sue Ryder, of the Sue Ryder Forgotten Allies Trust, addressing a press conference in London during which she launched an appeal for £250,000 for expansion of the work of the Trust.

Date: 10/11/1965

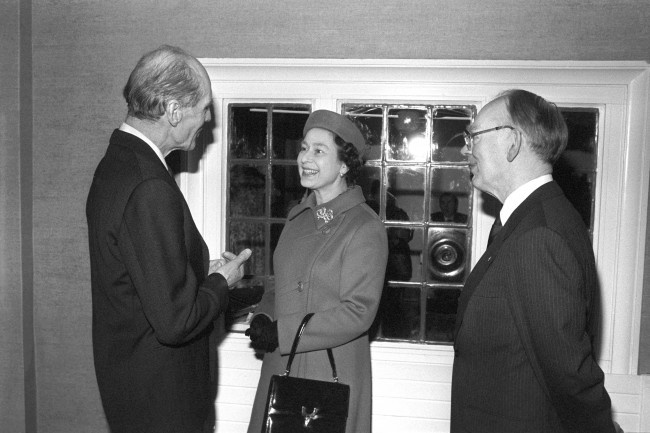

The Queen, talking to Group captain Leonard Cheshire, VC, at the Arnold House Cheshire Home in Enfield, when she opened a new wing at the home for disabled people.

Date: 09/02/1983

The Queen Mother chats to wing Commander Leonard Cheshire, a former commanding officer of 617 Squadron, the ‘Dambusters’, during a ceremony at RAF Marham to present the squadron’s new Standard.

Date: 13/01/1988

World War Two hero Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, later Lord Cheshire, with his wife Lady Ryder (Sue Ryder), among the poppies near the Lochnagar Crater on the Somme, paying their respects to the War dead.

*03/11/2000 Sue Ryder died, Thursday November 2, 2000, aged 77. She had been ill for some time and was admitted to Bury St Edmunds Hospital, Suffolk, in January 2000.

Queen Elizabeth II pets Harris, a PAT dog, during a reception for Leonard Cheshire Disability in the State Rooms, St James’s Palace, London.

Picture date: Thursday May 29, 2014. Photo credit should read: Jonathan Brady/PA Wire

Date: 29/05/2014

You can donate to the Leonard Cheshire fund here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.