Russian artist Vladimir Lebedev (1891 – 1967) spent a large degree of his talent making political cartoons and posters for the Soviet cause.

Beginning in 1913, Lebedev worked as a political cartoonist for several satirical journals, including Satirikon (Сатирикон), published in his home city of St. Petersburg.

When not doing politics, Lebedev collaborated with the poet Samuil Marshak (1887 – 1964), whom Russian writer and activist Maxim Gorky (1868 – 1936) called “the founder of Russia’s (Soviet) children’s literature”, illustrating more than a dozen books. His illustrations were also found in many children’s magazines.

As the mood shifted towards the promotion of Soviet ideology in all things, Lebedev was hired to create more than 500 posters, or placards, for the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) and the Department for Agitation and Propaganda (Agitprop). Placed in empty shop windows — known as ROSTA windows — Lebedev’s placards would promote the policies of the Communist Party and rouse the illiterate with their simple bold designs.

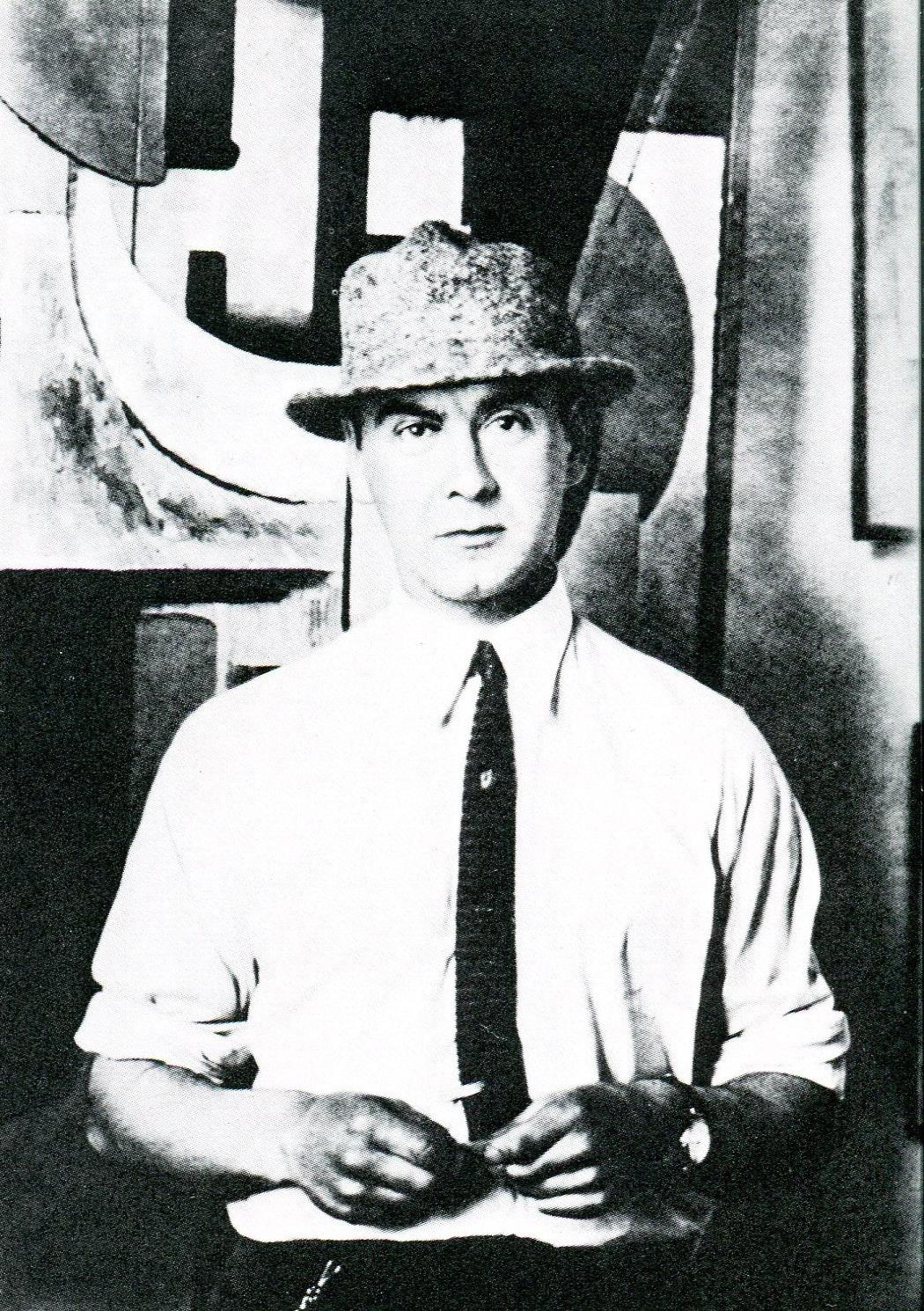

Vladimir Lebedev – 1920s

Lebedev’s work for children was not all fairies and talking dragons. Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869 – 1939), thought anthropomorphic animals and fairytales too unrealistic and liable to give children false notions of what life was really like.

An article in the monthly magazine Detskaia literatura (Children’s Literature), said of Lebedev: “Instead of concrete images of realistically rendered distinguished workers of the Soviet Union, Lebedev depicts schematic lifeless mannequins.”

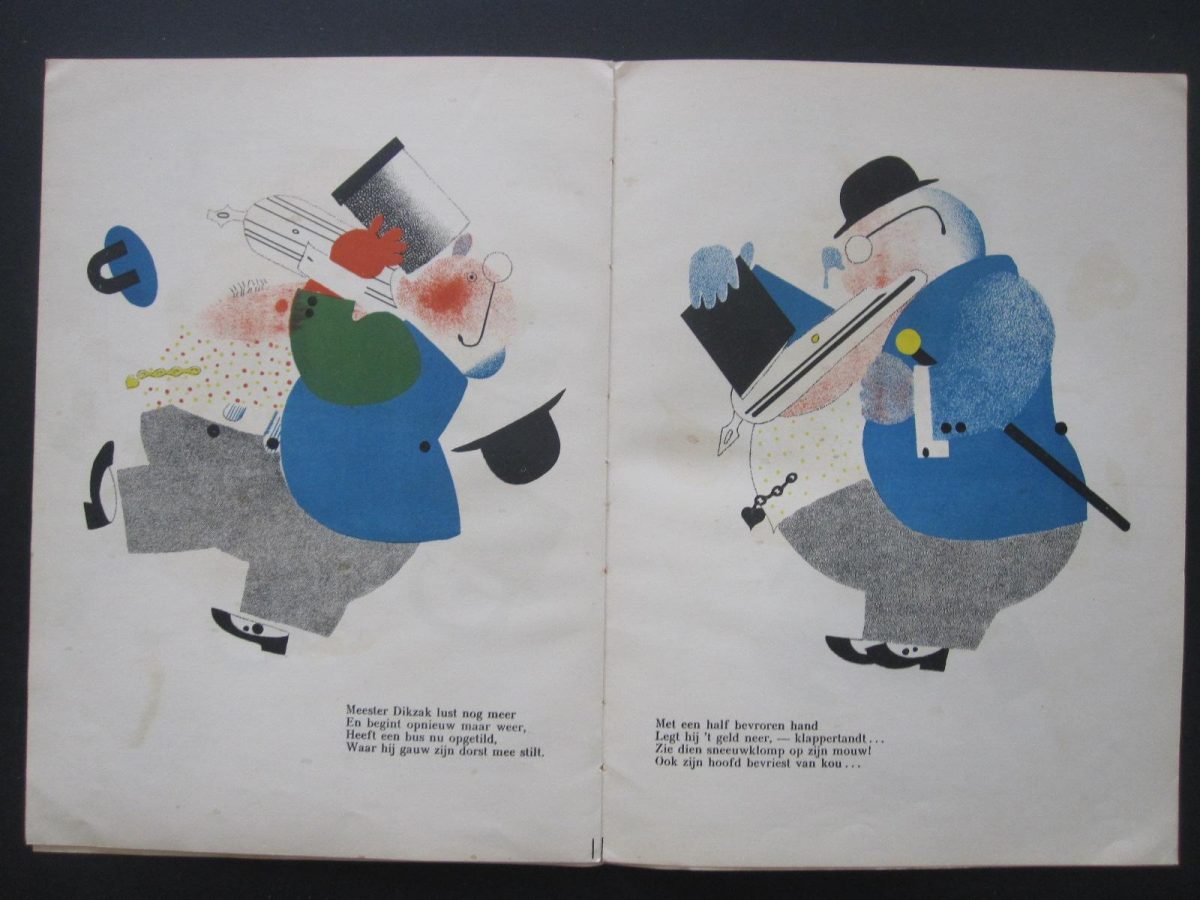

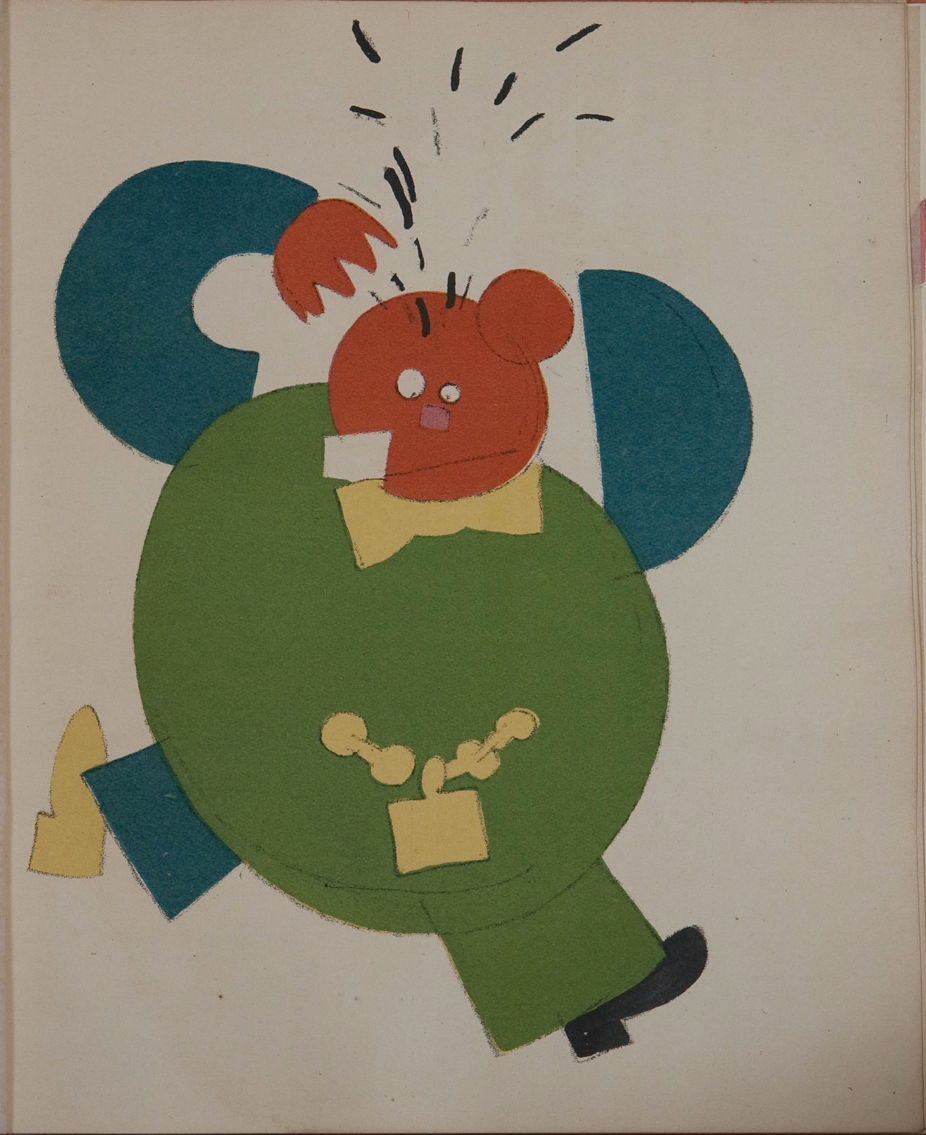

But before the clampdown in the 1930s, when Social Realism was centralised and managed by committee, there was some fun to be had in Soviet avante-garde picture books. In Marshak’s book Morozhenoe (Ice Cream, 1925), illustrated by Lebedev, we get the story of a greedy bourgeois man who eats so much ice cream that he causes a blizzard in the summer turns into a snowman.

Ice Cream was deemed too entertaining in some quarters, inferior to other children’s books Lebedev illustrated in adherence to the rules governing what made good art, like The Tale of the Military Secret – In Which A Little Boy Keeps a Big Secret and Saves the Communist Motherland (1933), Where Does Crockery Come From? (1924) and the 1930s bedtime page turner, The Board of Competition (Doska sorevnovaniia, 1931), created in the context of the Five-Year Plan introduced by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in 1928 with the aim of ending private commerce, achieving rapid industrialisation, and creating new “production targets” for factories.

Arkady Ippolitov, a curator at the State Hermitage Museum in Russia, writes in the preface to Inside the Rainbow, a compendium of Soviet-era picture books from the 1920s and 1930s: “In order that children would mesh with the radiant future being built for them, they themselves had to be rebuilt… thus the education of children was the most vital affair in the new Land of the Soviets. [And] books play a quite important role in children’s education.” Right on.

Lev Kormchy had much the same to say in Pravda in 1918: “In the great arsenal used by the bourgeoisie to fight against Socialism, children’s books occupied a prominent role. In choosing our cannons and weapons, we have overlooked those that spread poison. We must seize this ammunition from the enemy hands.”

Lebedev found himself at the forefront of the culture wars and a pressing need to survive them.

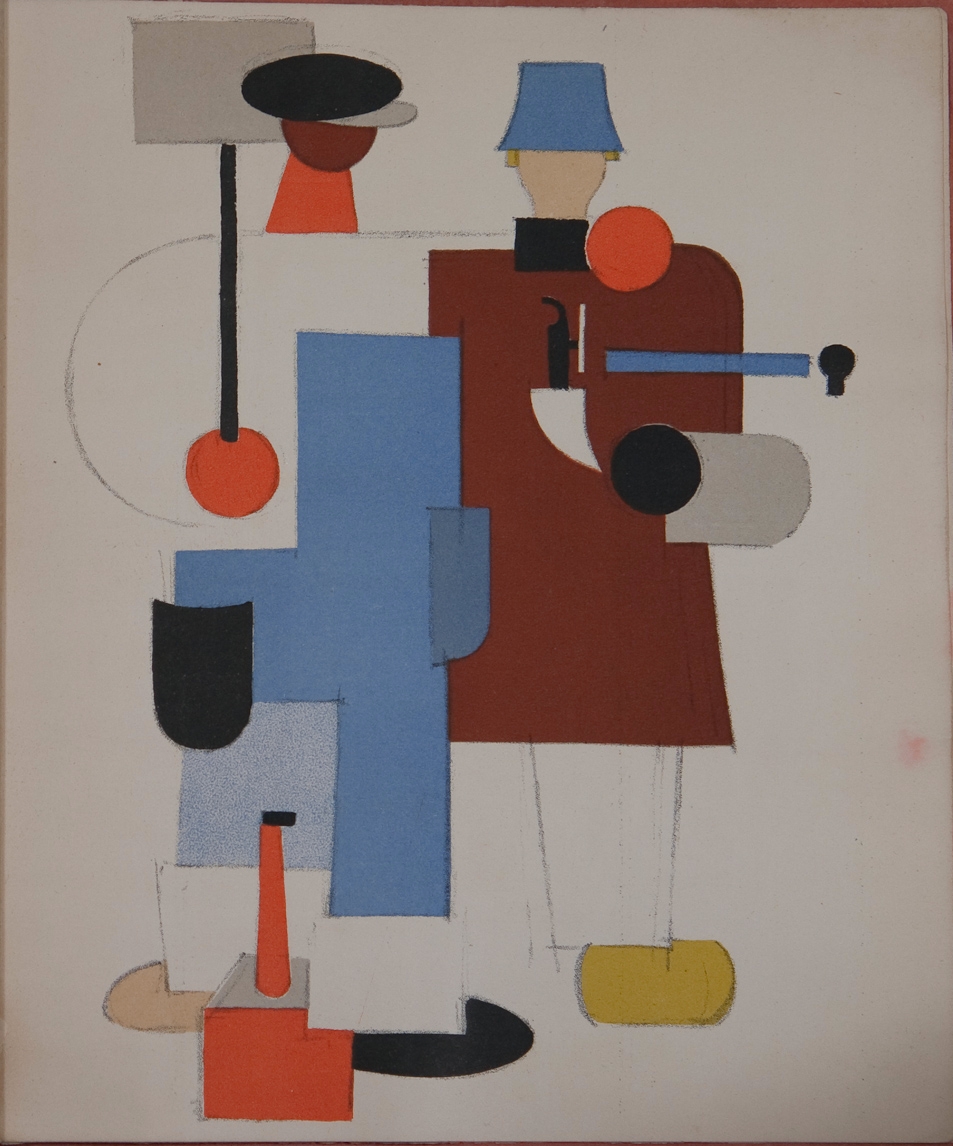

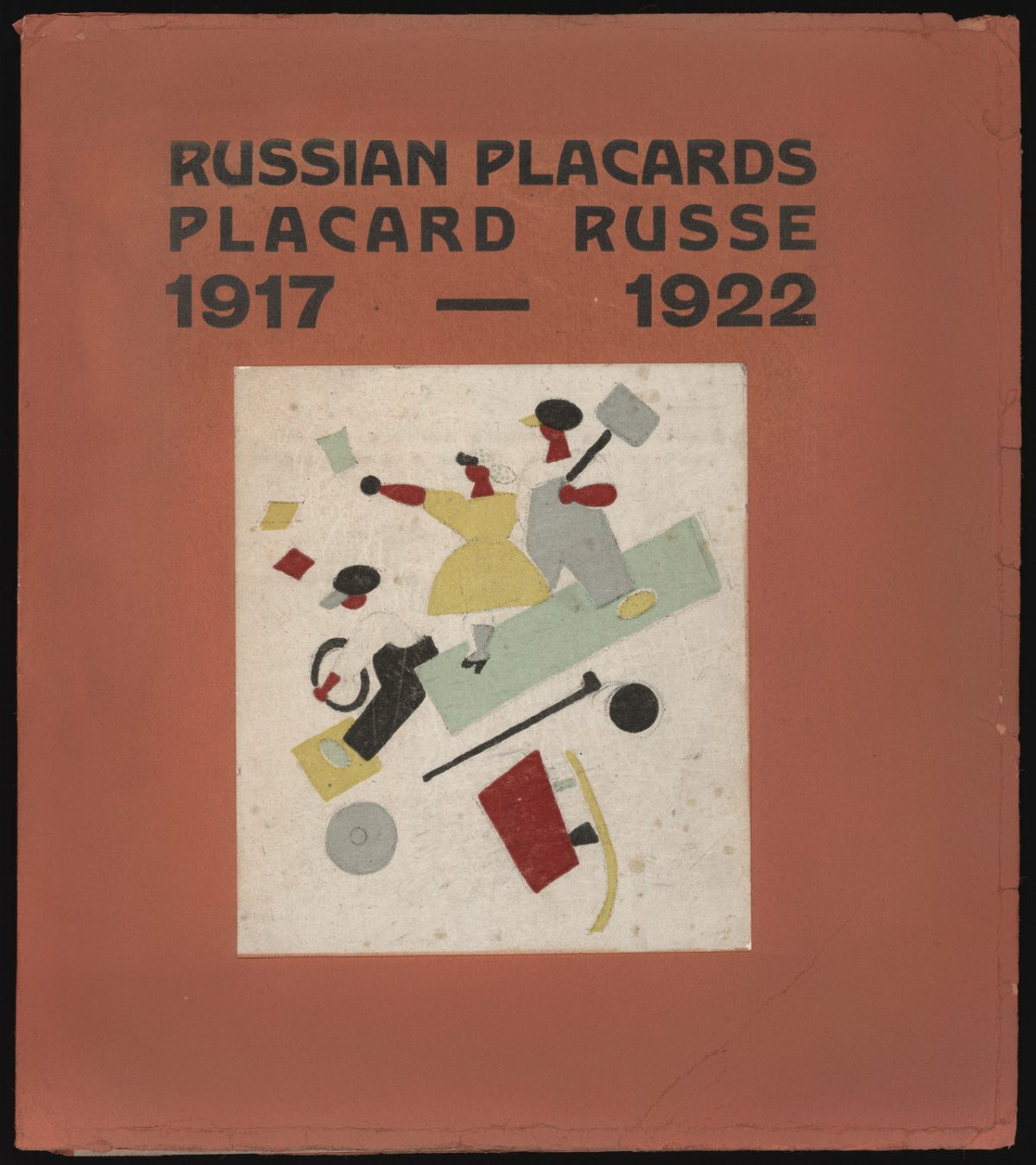

But he did have some fun with these brilliant illustrations for Russian Placards, Placard Russe 1917-1922, published by the St. Petersburg: Petersburg Branch of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee, with bilingual text to present the posters to the rest of the world.

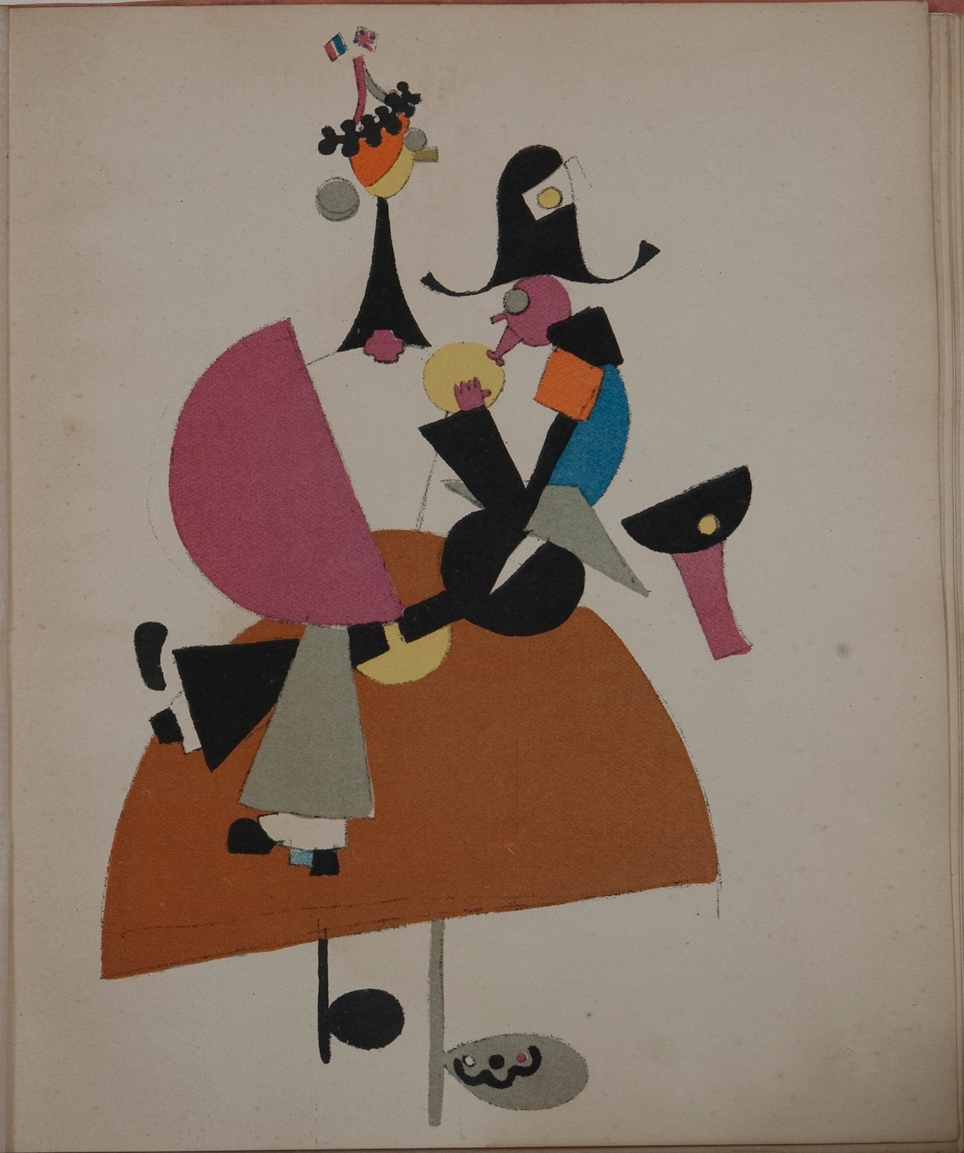

The Entente gives suck to Koltchak. Entente— a puppit (sic) decorated with a garland and the Tower of Eiffel,

the latter with British and French flags on It. Koltchak in a three-cornered a pistol case on his back.

Productive propaganda. A caster with a casting spoon in his hands, a mould in the left corner.

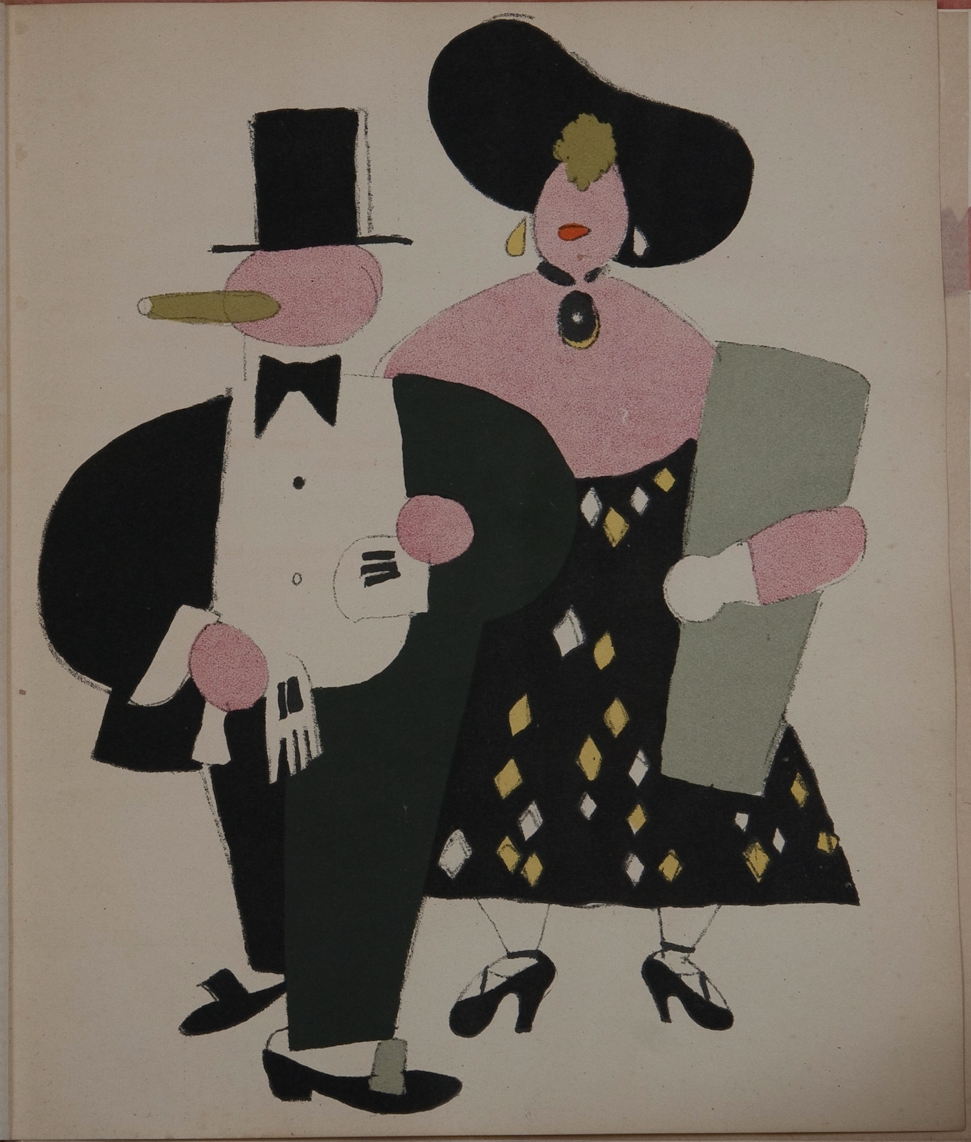

Agitation for utilizing the bourgeoisie for proletarian purpose. The bourgeois in a grey top-hat and apron waits

upon the workman (feeds him with fish).

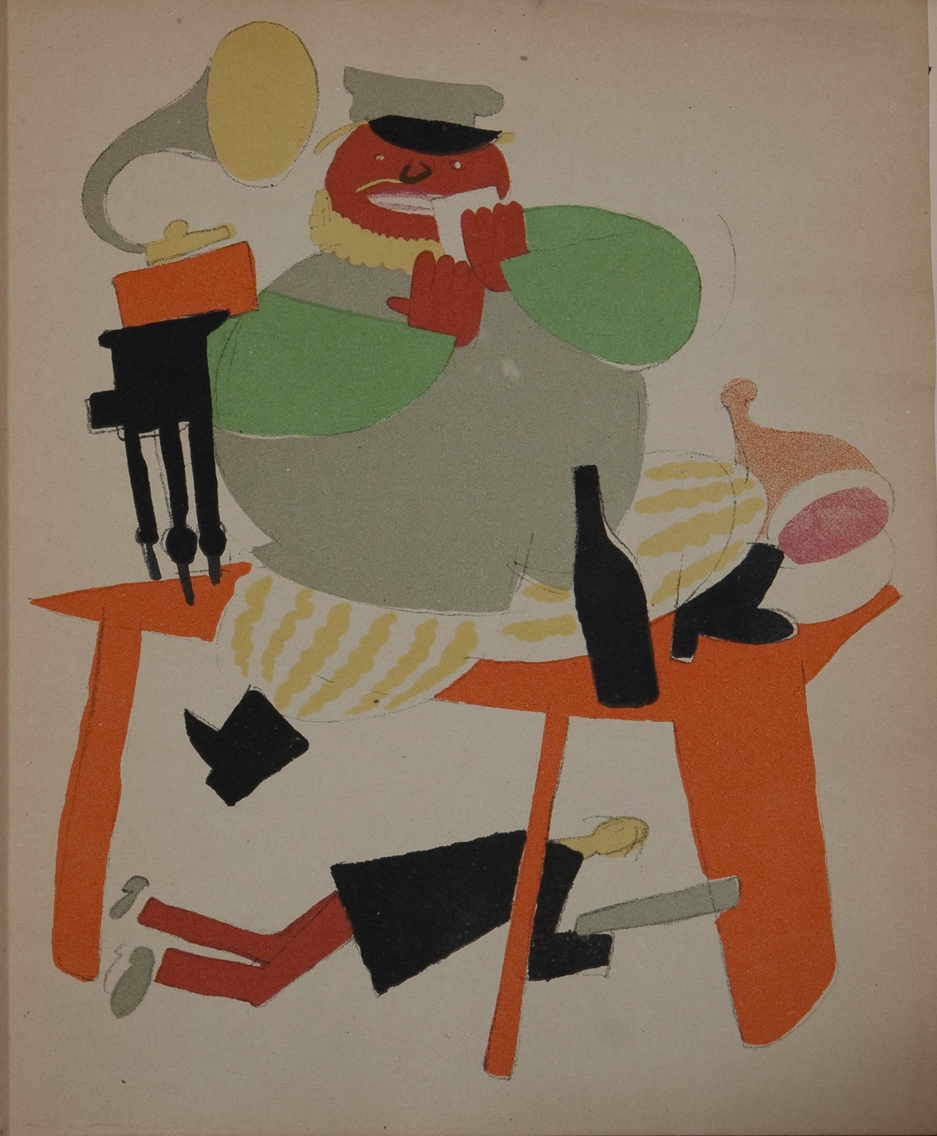

Agitation for the closing of markets- “the marauder in heaven and the simpleton in hell”. The placard represents an owner of a market- stall sitting in a grand house at a table with provisions and a gramophone standing on it, while a starving citien under the table is defending the markets.

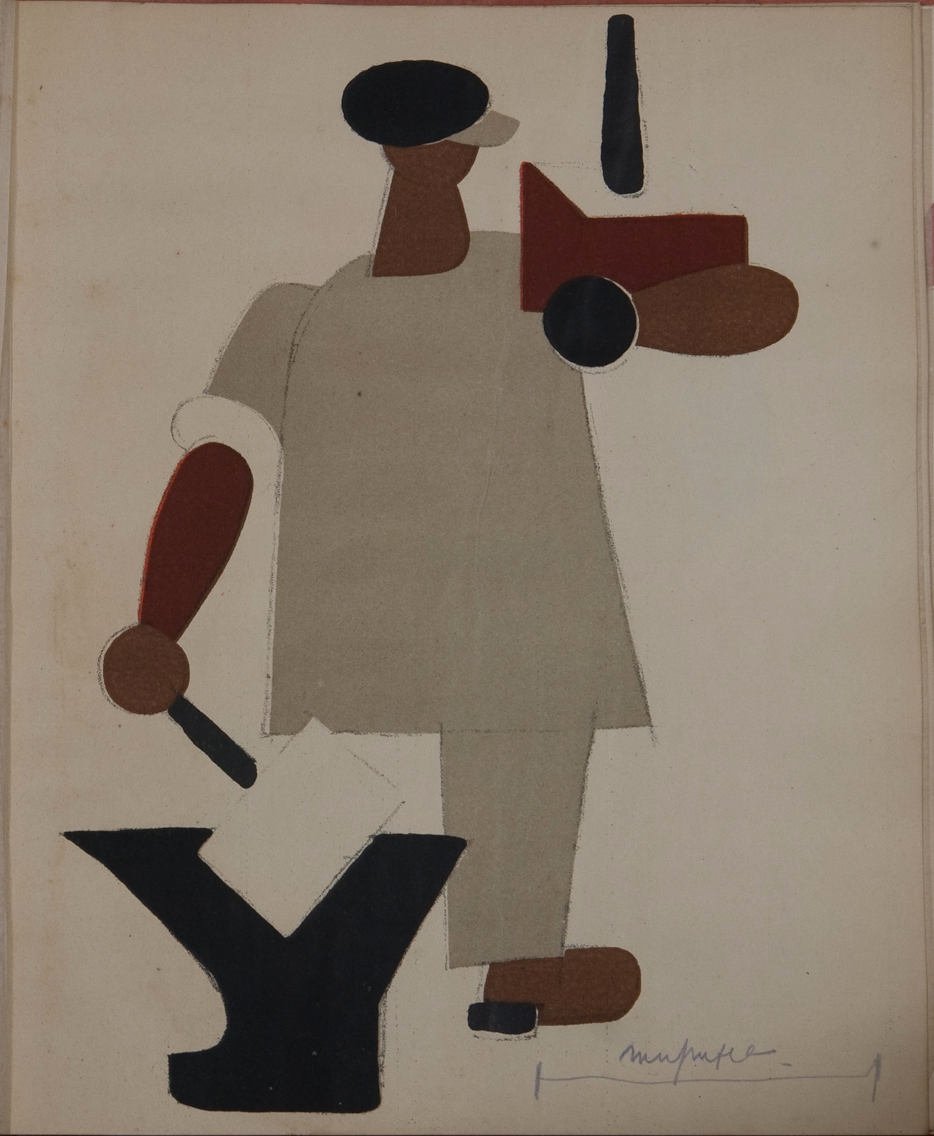

A workman with nationalised enterprises in his hands.

A work-woman. (Raising productivity through joining together small hand-working and trade industries).

The red vision of Communism is brushing over Europe. The placard represents the bourgeois saving themselves from two workmen.

The new bourgeoisie In the Republic of labour (threat to the proletarian State)

Images via Paul K on Flickr.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.