“I thought that if people saw themselves, in photographs, they would understand each other. I even believed you could prevent wars and things. I gave up those beliefs a long time ago.”

– Gisèle Freund

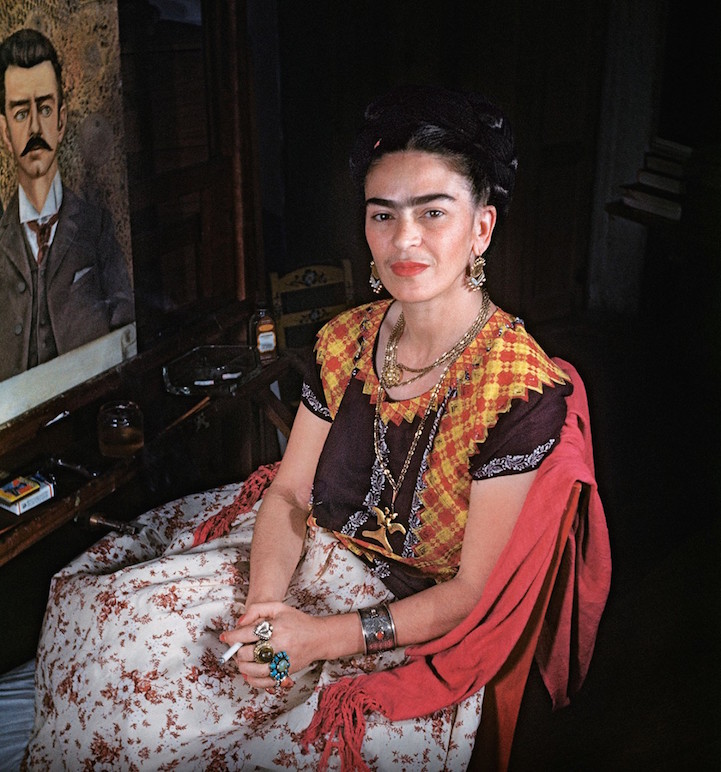

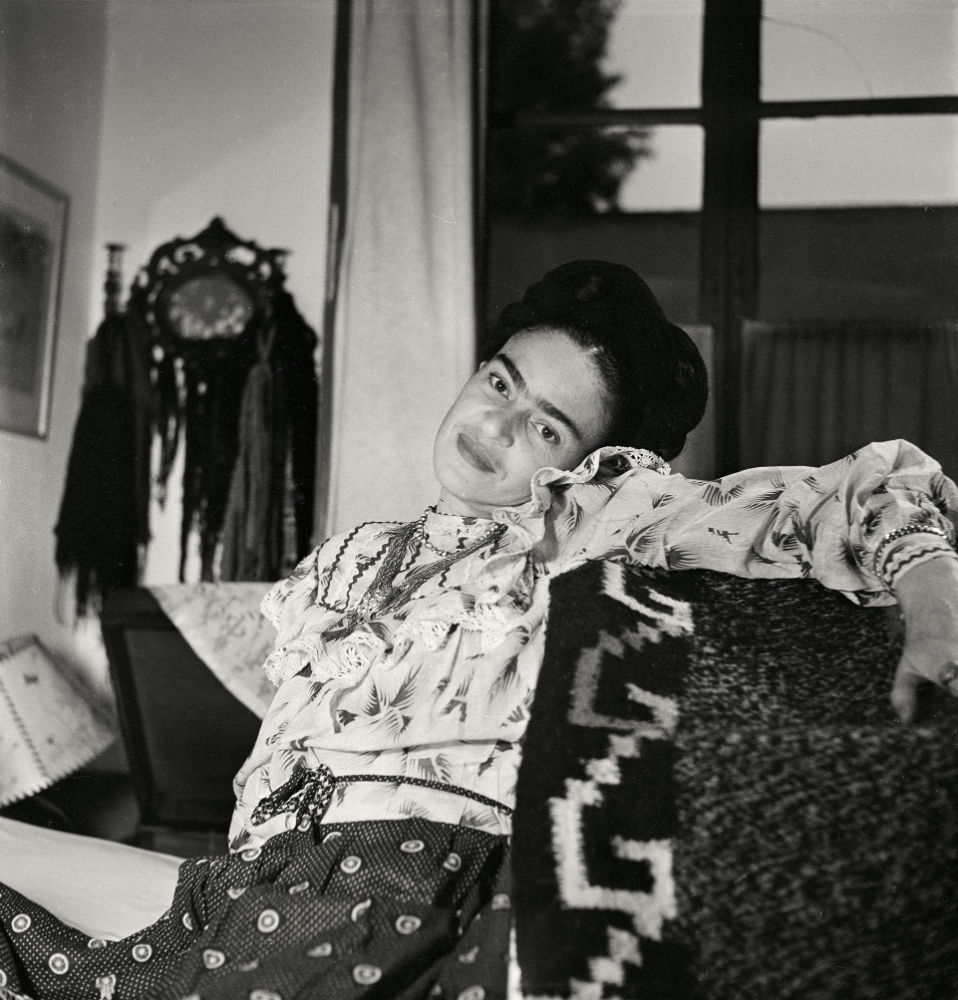

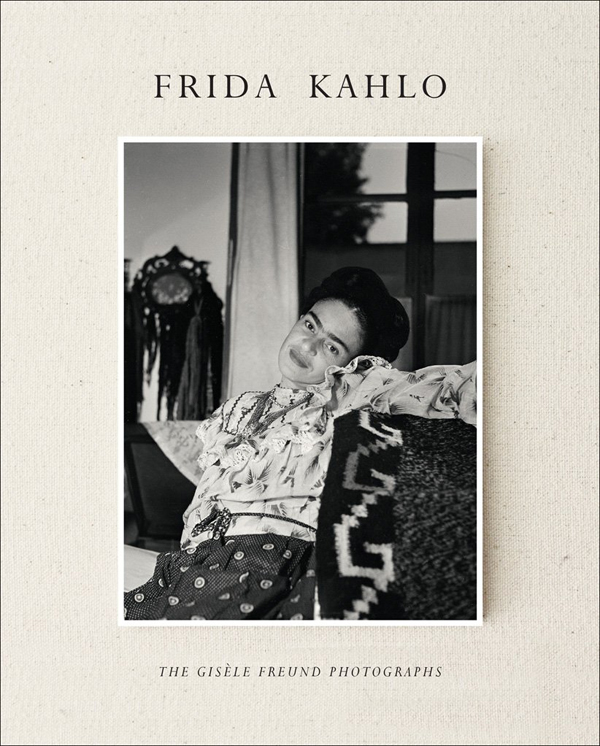

These photographs were taken of the artist Frida Kahlo (1907 – 1954) in the final years of her life. For two years, photographer Gisèle Freund (1908–2000) was welcomed into the home of Kahlo and her husband and fellow artist Diego Rivera (1886–1957), allowing her to document their daily lives.

As a Jew and an active opponent of National Socialism, Freund was told to leave her native Germany. In 1933, she headed to Paris and 1936 earned her PhD with a dissertation on the social impact of photography.

In her memoirs, The World in My Camera, Freund wrote:

On June 10, 1940, the government left Paris. Three days later, directly before the German troops arrived, I left at dawn on a bicycle – the trains were no longer running. On the rack I had attached my little suitcase, the same one I had brought with me to Paris seven years before. I found asylum in a small village in the Dordogne. Several weeks later, I was informed that my husband had been made a prisoner of war. He got word to me that he would try to escape and succeeded a few months later. I met him in the still unoccupied part of France. He told me he would go back to Paris to fight the Germans in the Resistance, and advised me to leave the country as soon as possible. Being of German origin, undoubtedly listed by the Gestapo, and now the wife of an escaped prisoner as well, I actually feared for my life.

In 1942, after two years in hiding, she left occupied France for South America. There, she became cultural attaché for the Ministry of Information of Free France, and founded “Ediciones Victoria” to publish books about France.

Invited to lecture in Mexico, where she lived for two years, Freund became friends with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

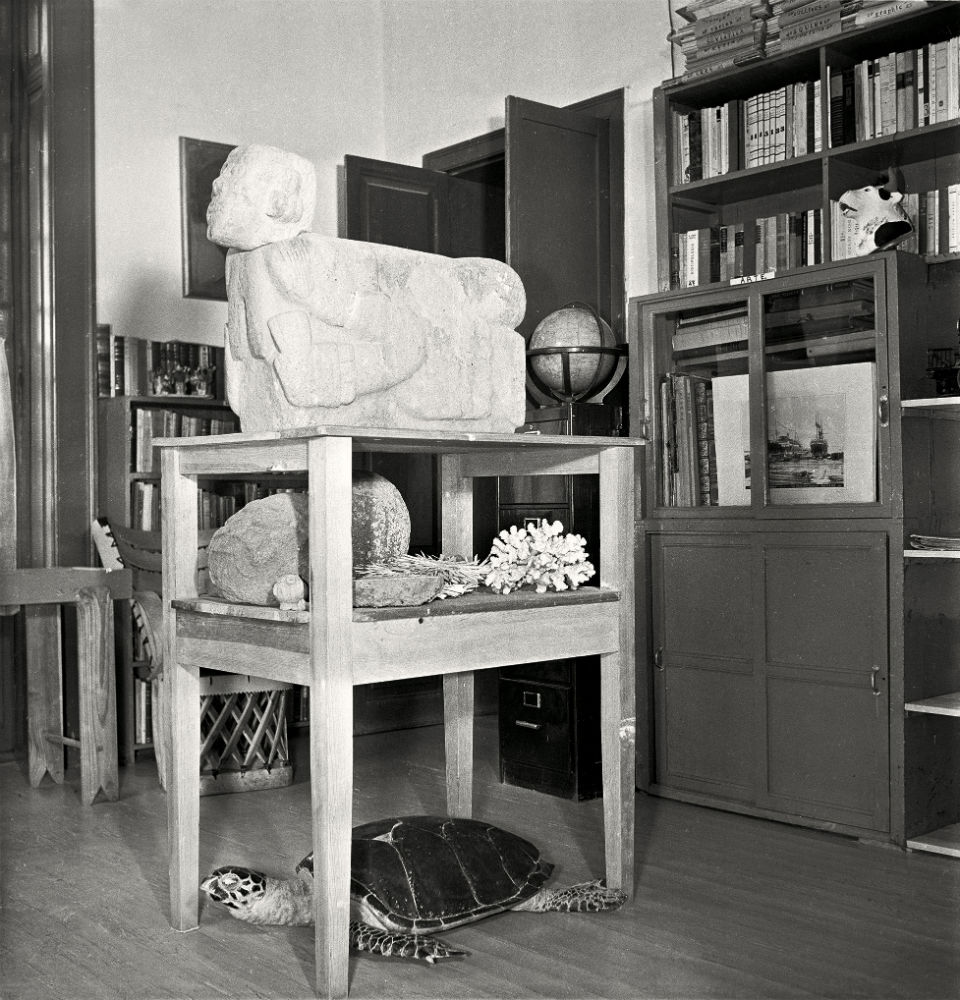

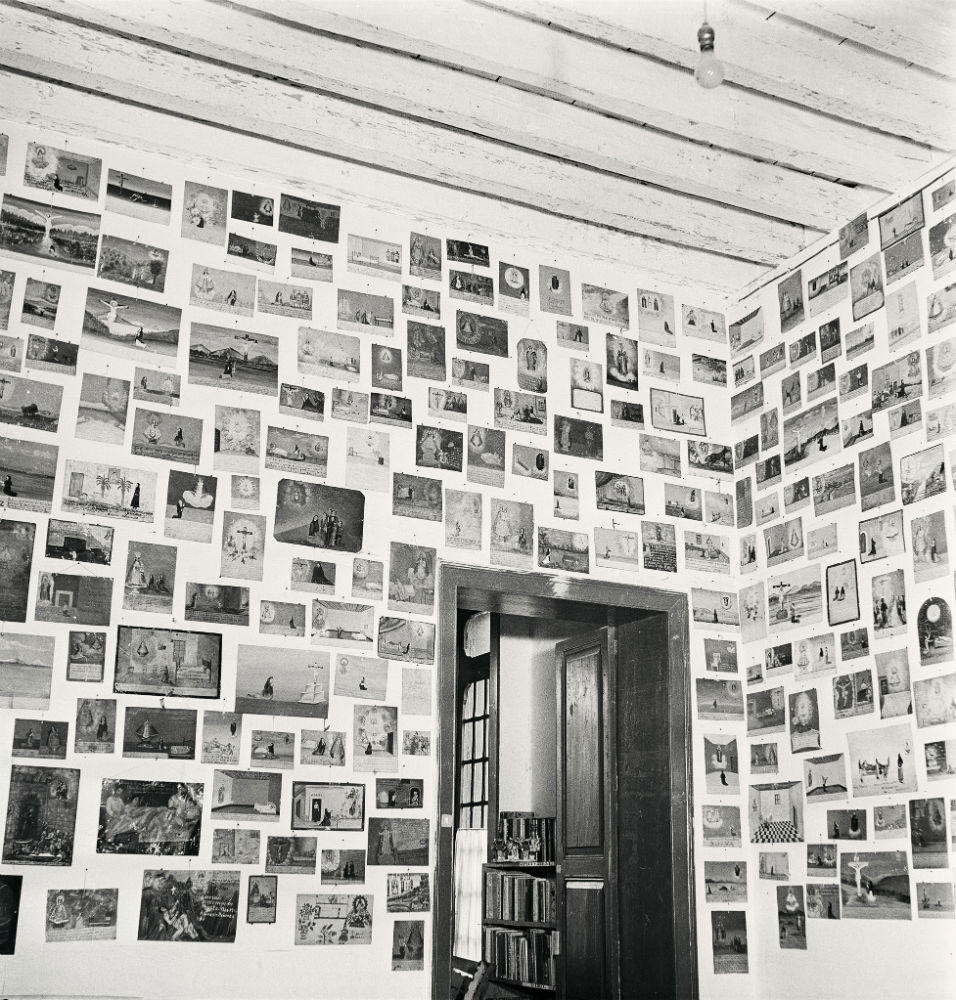

As well as portraits of Kahlo in bed, at her easel or in her beloved garden, Freund documented the interior of the Casa Azul, including the artist’s desk and studio. “I always preferred photographing a person in his private space, among his belongings… And the decor of a home reflects the person who inhabits it,” she wrote.

In 1994, Freund recalled her time there in an interview with Kirsten Martins:

Frida was delightful, so wonderfully alive and almost completely paralysed. I don’t know how many operations she had had on her spine. When I arrived in 1950, she could still walk a little. Later she took terrible medications and there were days when she couldn’t see anyone because the pain was so bad. But she was so amusing and so alive. I had many letters from her. She wrote them like a diary, but they’re gone now, stolen perhaps, I’ve never found them again. Frida was a very lively woman. She told me, “I don’t care if I die young, but I want to get something out of life”.

And Diego?

Well, whenever I was there, they were having awful rows. And the irony of it is that Frida told me once, I hope to God that Diego dies before me, because he can’t manage without me, and then she died before him, and three months later, he married another woman. They loved each other dearly. We were very good friends, and Diego was interested in a lot of things. He spoke French fluently, having lived in Paris for years as a painter. Right away he told me he would show me what others had never seen, the dances and fiestas of these people, and he always took me along to them. Then, one day, I asked him if I might borrow his sketchbook, because I wanted to photograph some pages from it. This I did because he drew these incredibly wonderful women. I took the photographs and returned the book to him. He asked me then how many pages I had taken out. I said “none, Diego, how could you think such a thing?”. He replied that it was obvious you weren’t an American. It would never have occurred to me to steal!

“It is not my intention to create works of art or to invent new forms. I merely want to show what is close to my heart – man, his joys and sorrows, hopes and fears.

“I believe that a good basic training in sociology and psychology, a mastery of foreign languages and the ability to come to terms with all situations are more important for a professional photojournalist than attendance at a school of photography. But the most important quality of all is the ability to love people.”

– Gisèle Freund

“The lens, the so-called impartial eye, actually permits every possible distortion of reality: the character of the image is determined by the photographer’s point of view and the demands of his patrons. The importance of photography does not rest primarily in its potential as an art form, but rather in its ability to shape our ideas, to influence our behavior, and to define our society.”

– Gisèle Freund, Photographie et société

In 1947 Freund had signed a contract with Robert Capa (1913–1954) and Henri Cartier-Bresson’s (1908 – 2004). Freund had returned to Paris in 1953, making it her permanent home. By 1954, at the height of the Cold War, Freund was blacklisted in America, declared an undesirable by the FBI, and pressured to break with Magnum in 1954.

Gisèle Freund spent the rest of her life in France. She became president of the French Federation of Creative Photographers in 1977, and in 1980 was the first woman to receive the Grand Prix National des Arts from France. François Mitterrand (1916–1996) appointed her an Officier des Arts et Lettres in 1982, and Chevalier de la Légion d’ Honneur the following year. In 1991 she was the first photographer honored with a retrospective at the Musée National d’art Moderne in Paris.

The book, titled “Frida Kahlo: The Gisèle Freund Photographs”, can be purchased on Amazon Here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.