“There were five of us — Hanssen, Wisting, Hassel, Bjaaland, and myself. We had four sledges, with thirteen dogs to each.”

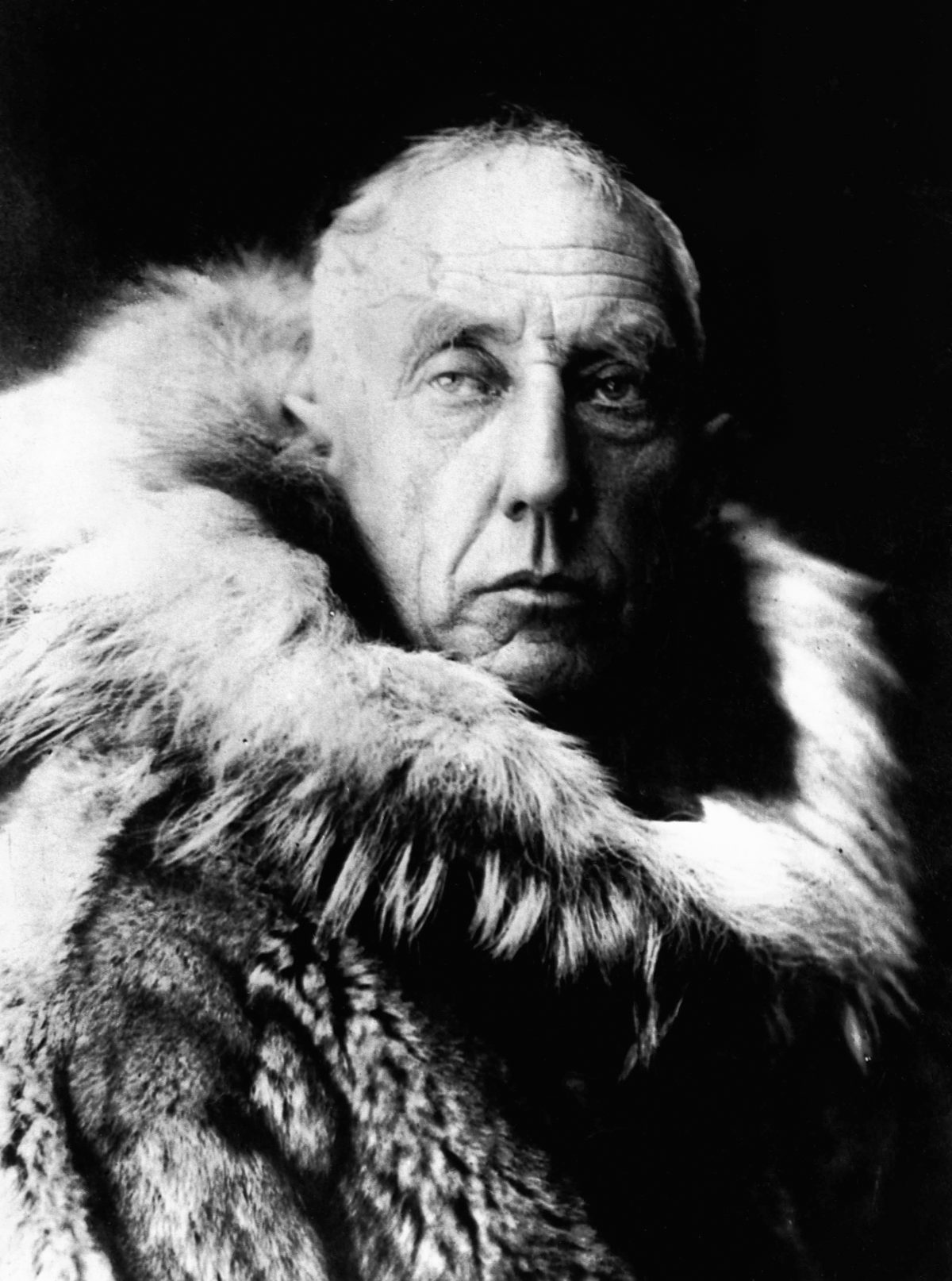

– Roald Amundsen (6 July 1872 – c. 18 June 1928), South Pole Expedition – 1910-1912

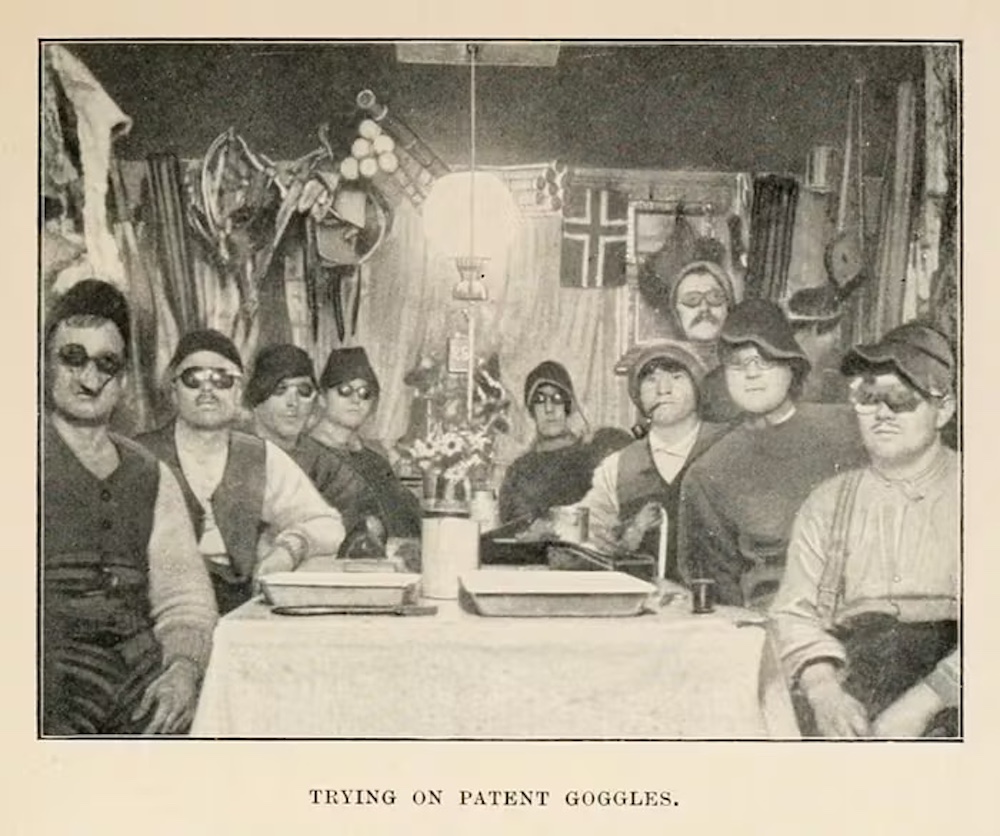

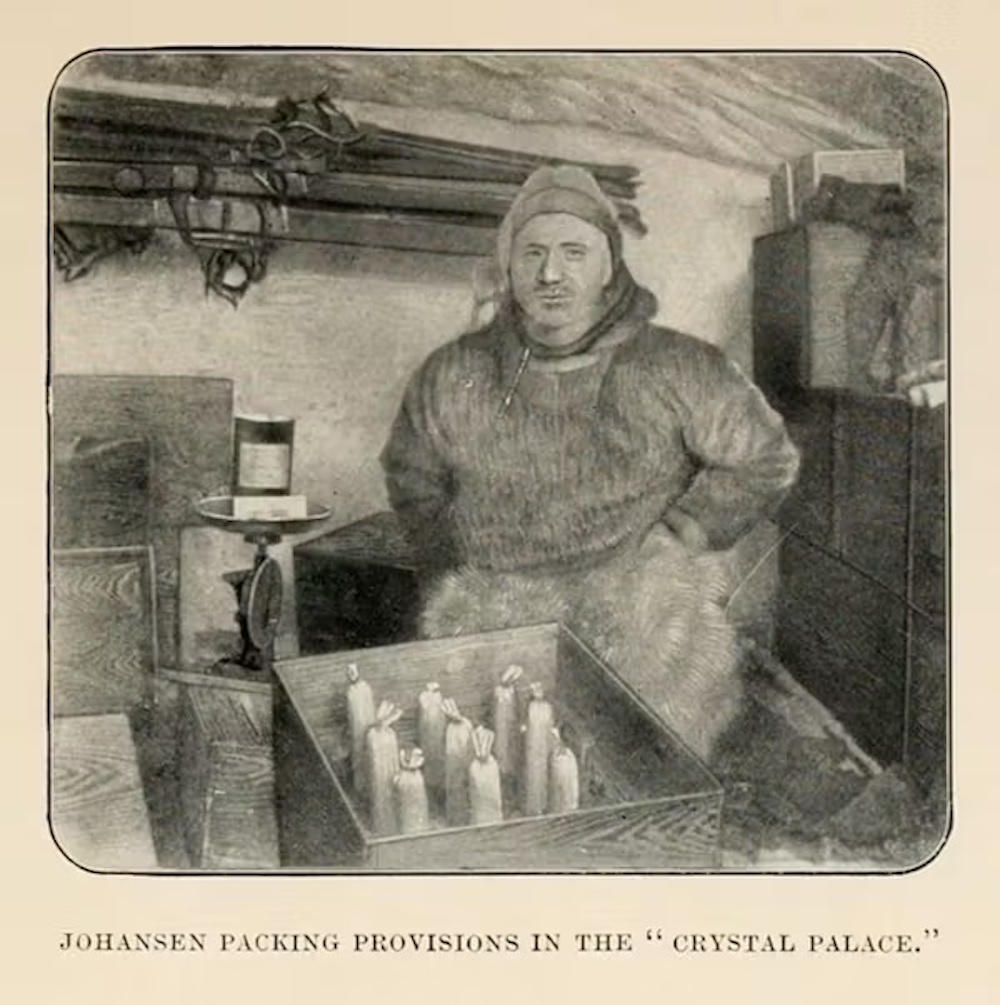

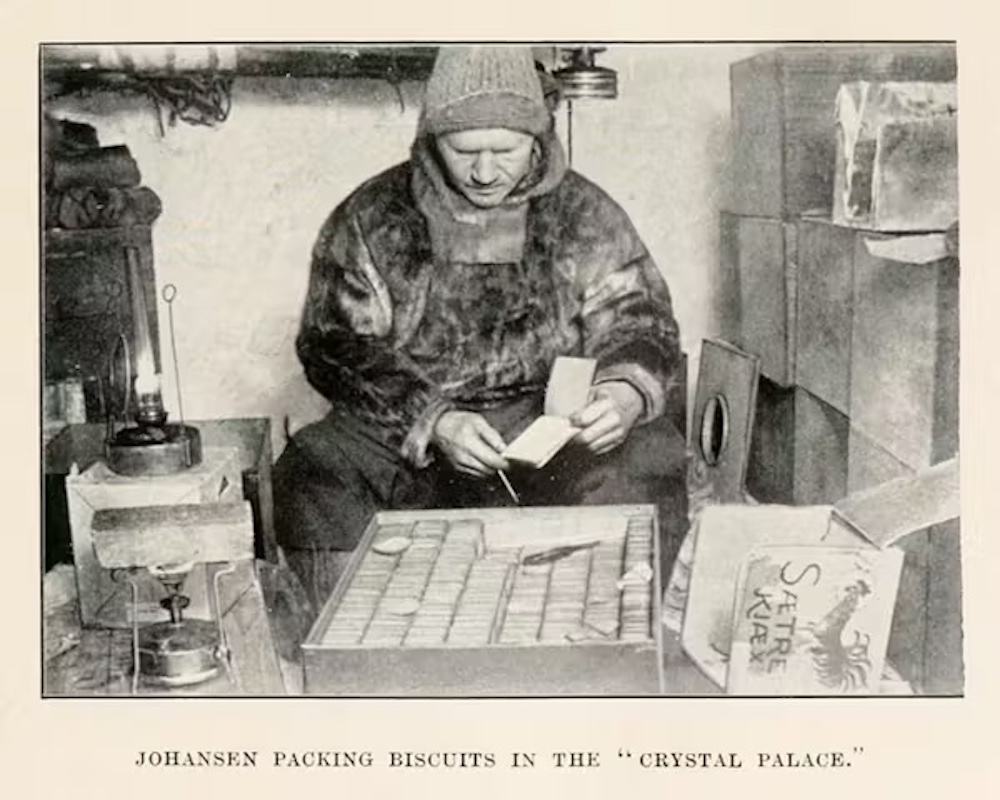

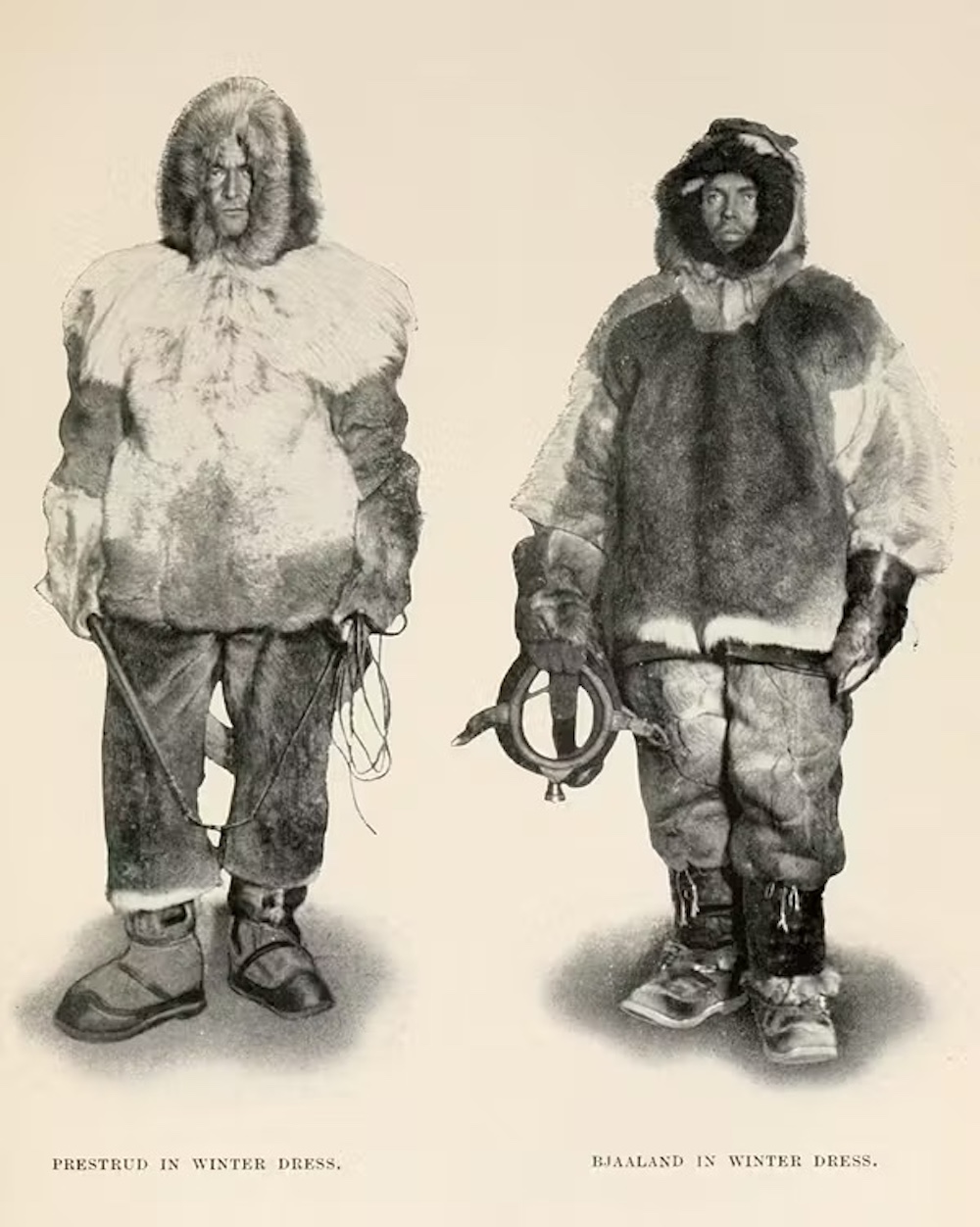

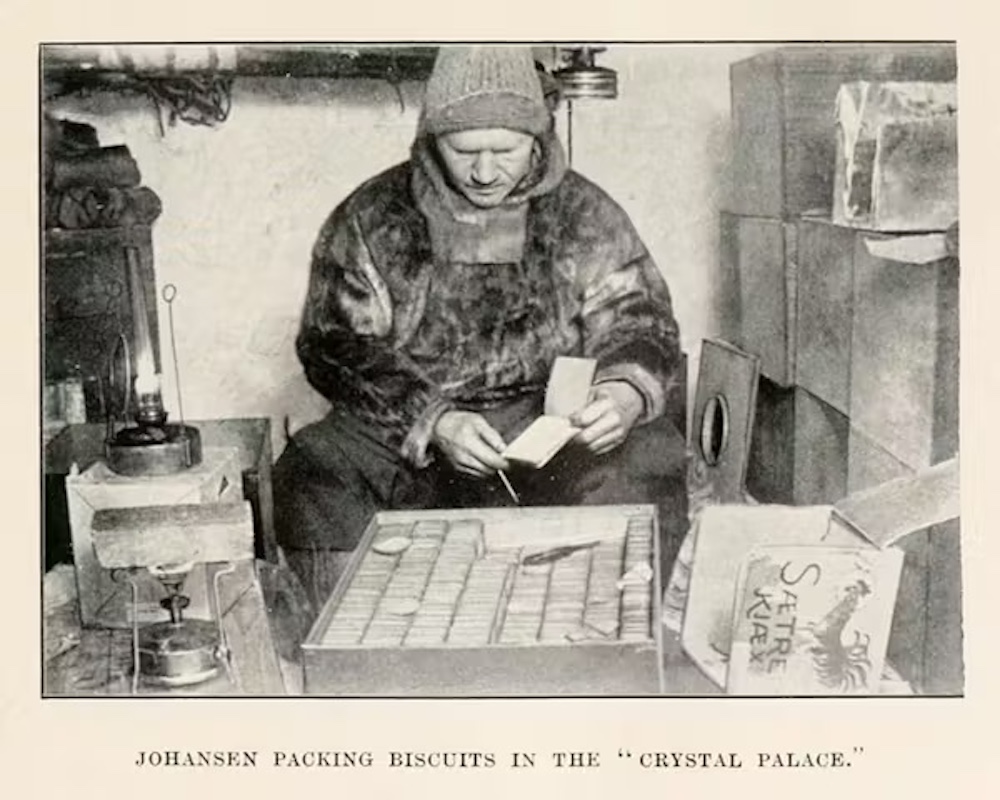

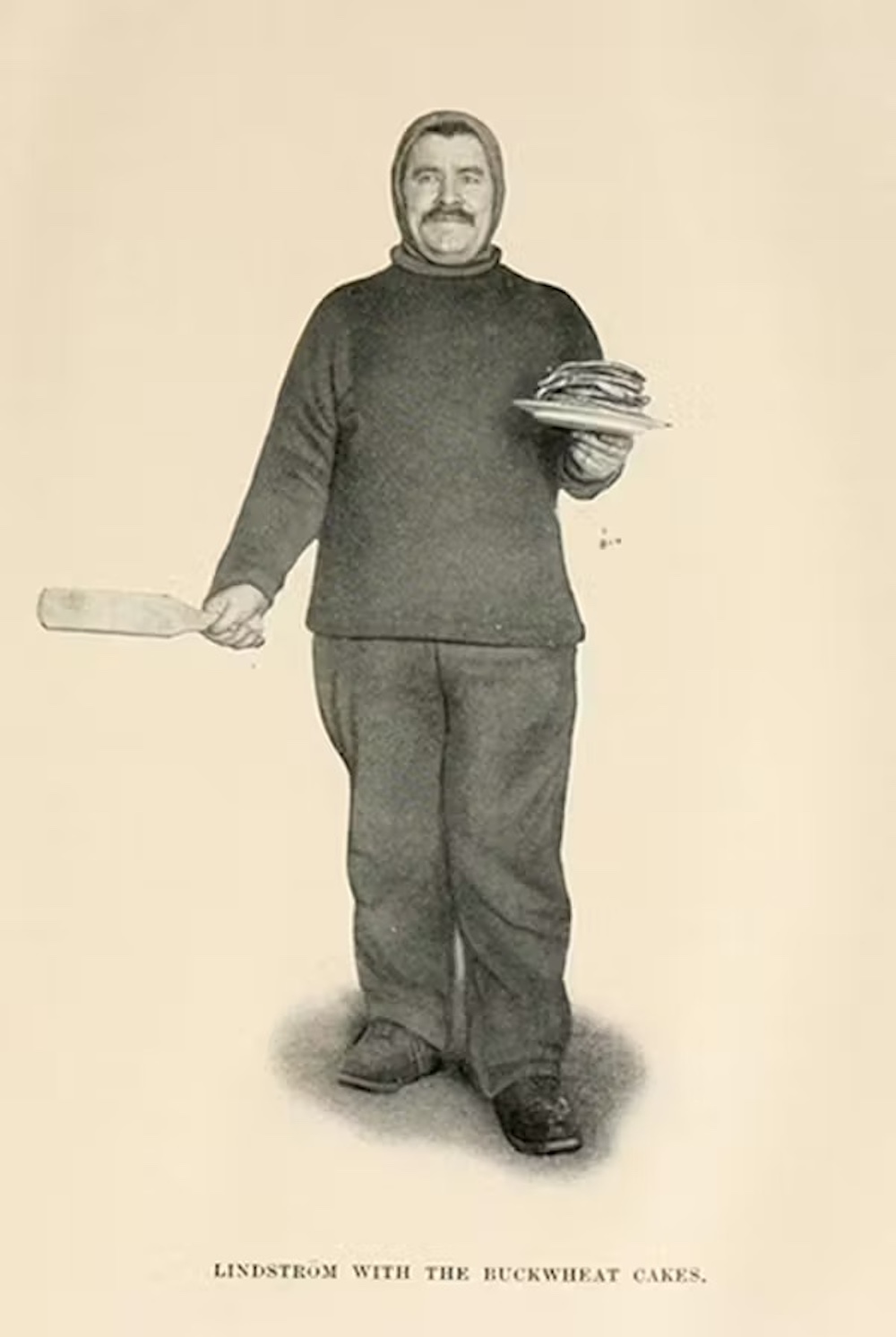

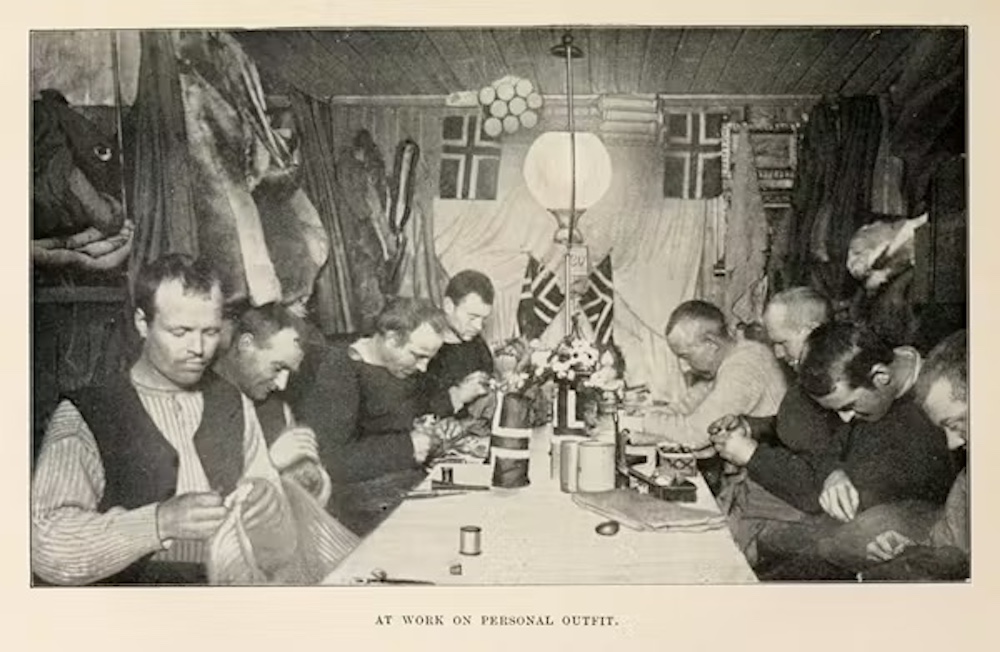

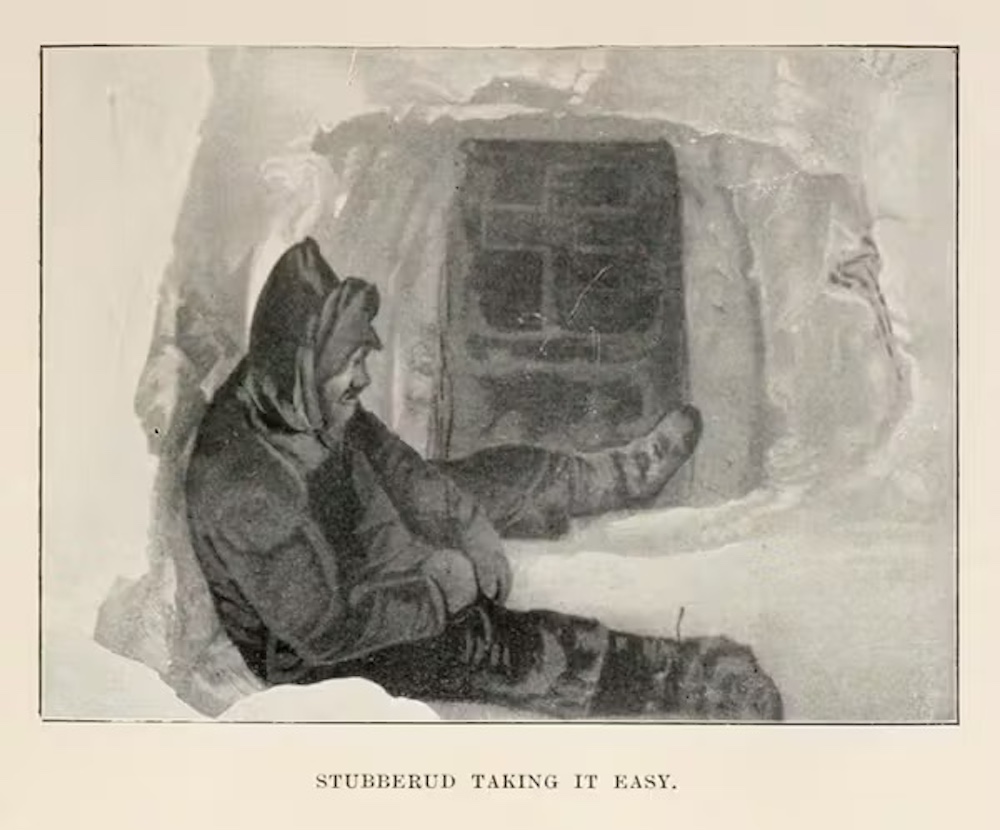

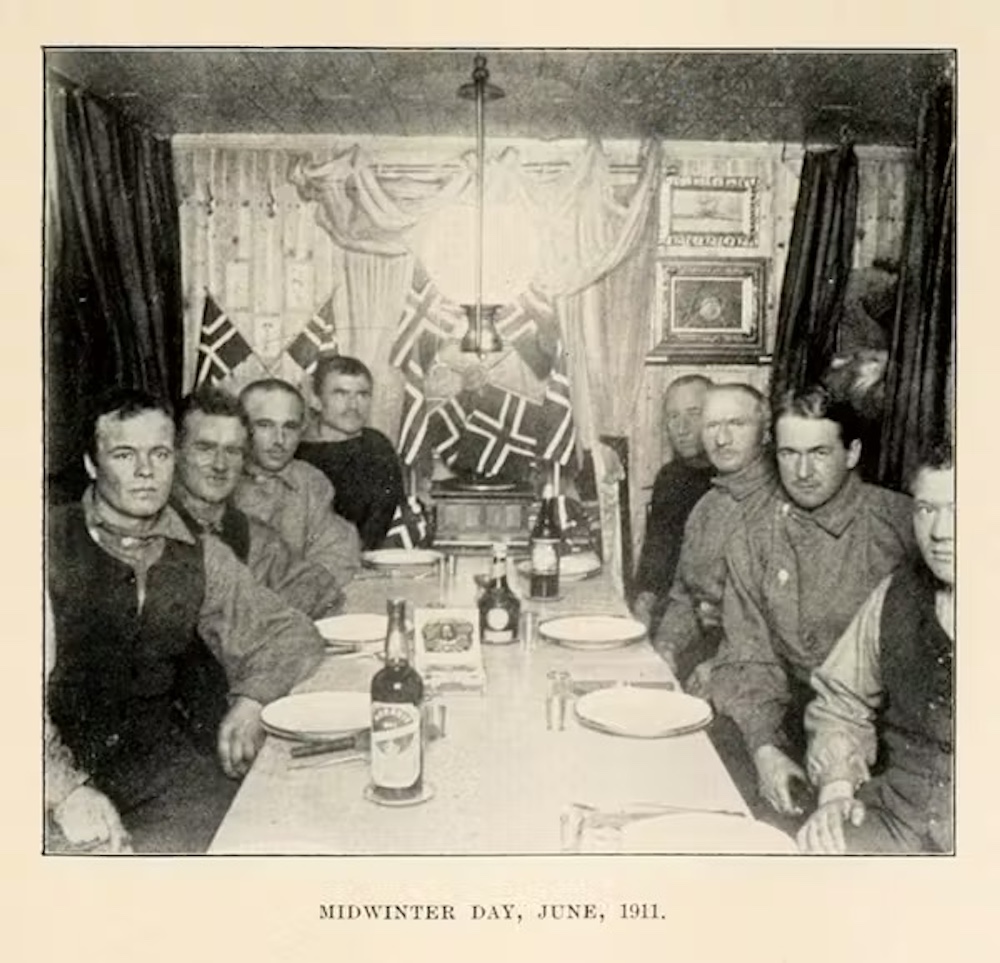

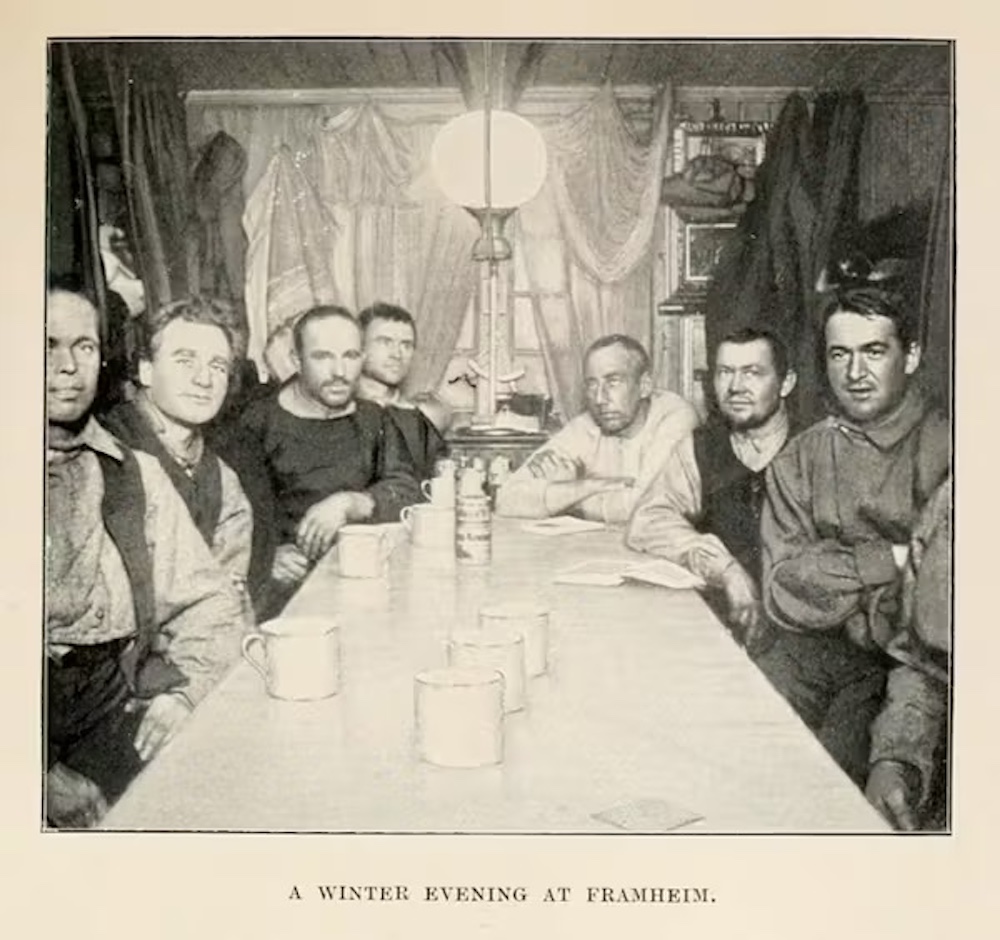

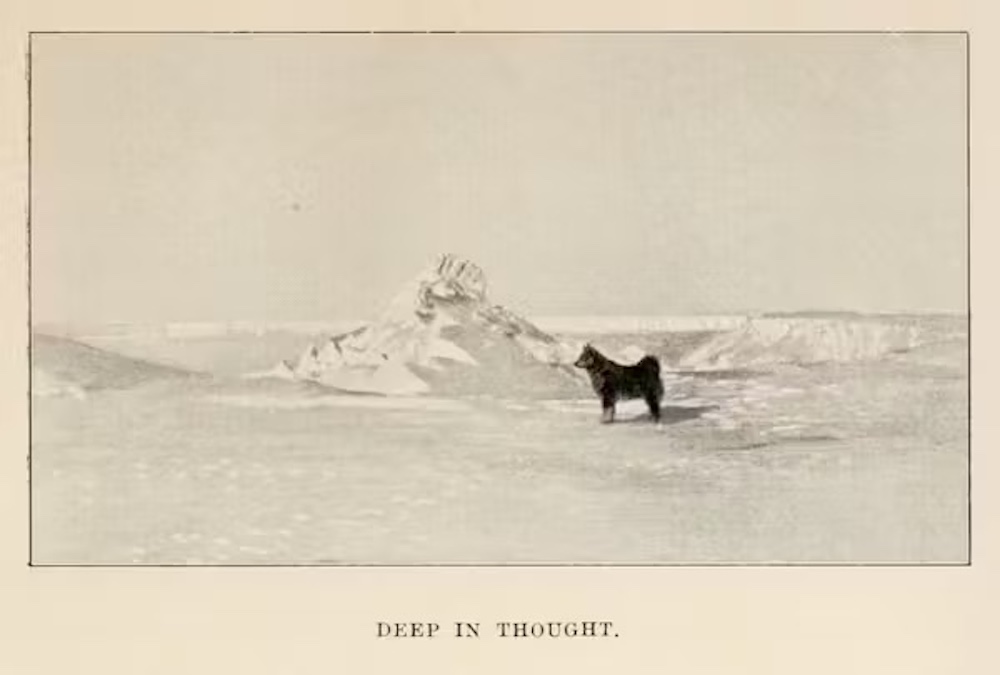

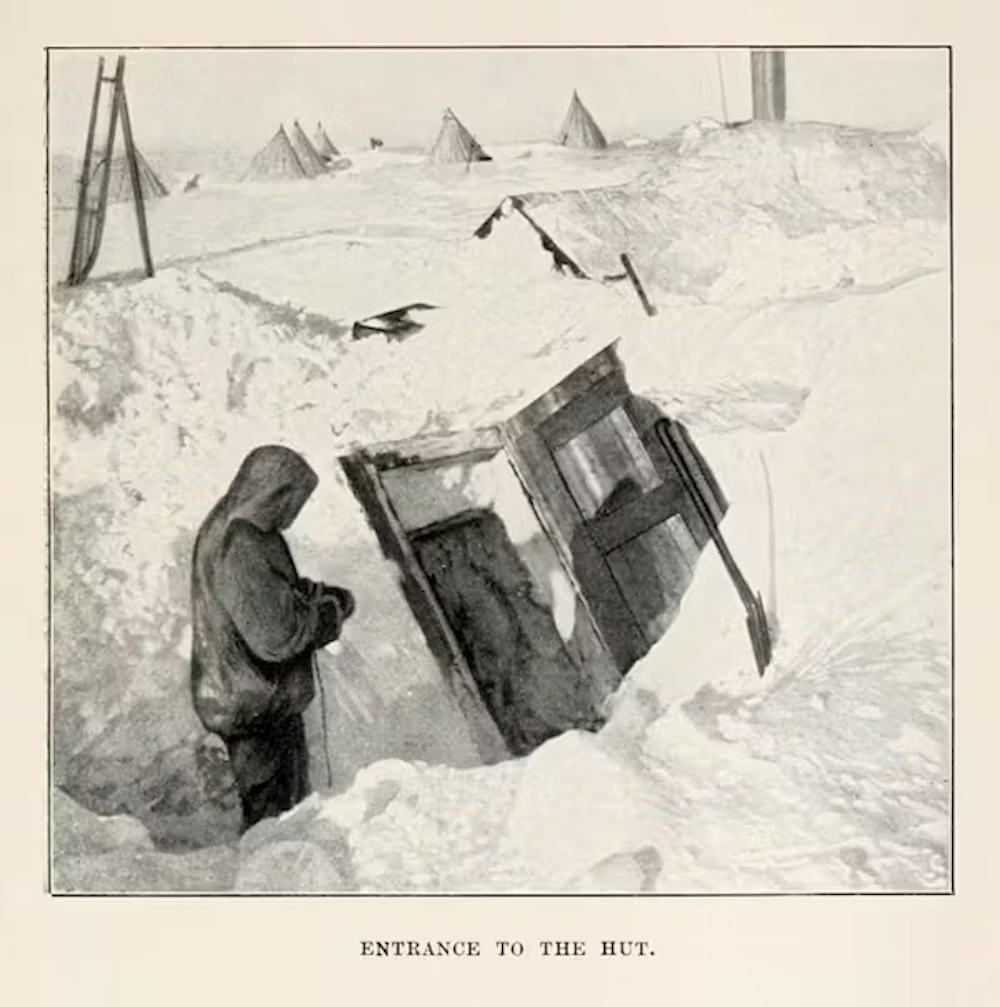

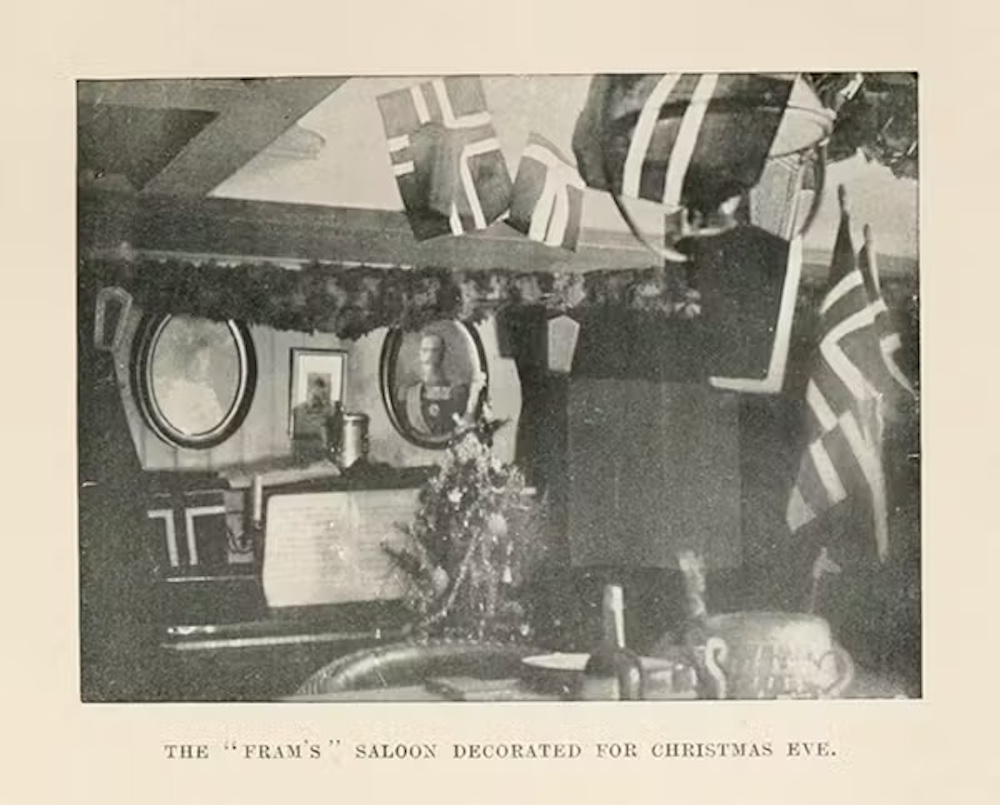

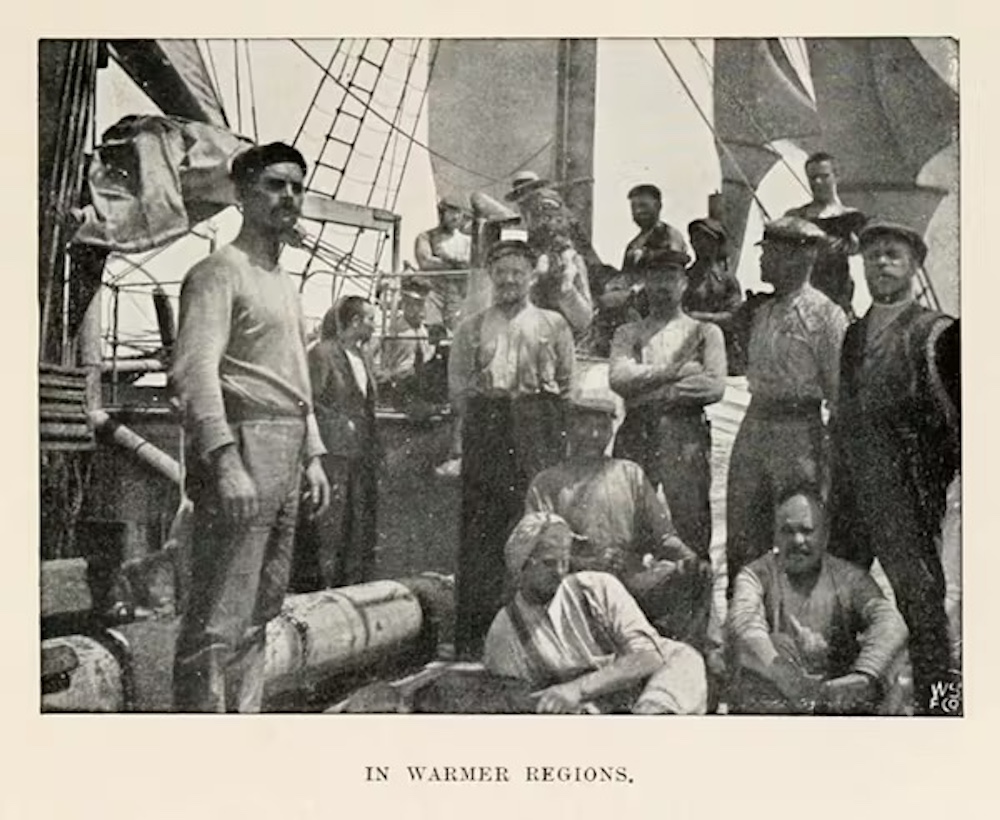

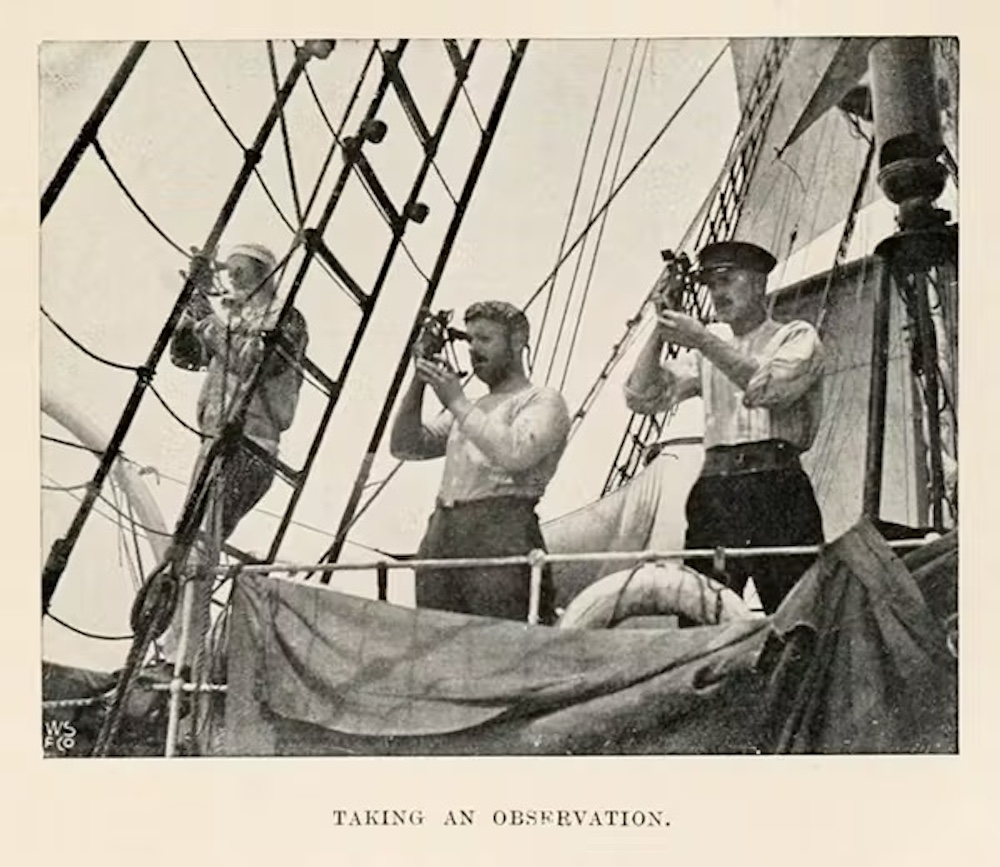

These photographs are found in the page of The South pole; an account of the Norwegian Antarctic expedition in the “Fram,” 1910-1912, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen’s account of his journey to reach the South Pole, which he achieved on 14 December 1911 – five weeks ahead of the doomed British expedition party led by Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912).

Amundsen is modest in his account of derring-do. But this was a dangerous journey, something starkly illustrated by the story of Scott and his team. On 17 January, they reached the Pole, only to find that Amundsen’s party had beaten them there. They started the 1,500 km journey back. Evans died in mid-February. By March, Oates was suffering from severe frostbite and, knowing he was holding back his companions, walked out into the freezing conditions never to be seen again. The remaining three men died of starvation and exposure in their tent on 29 March 1912. They were in fact only 20 km from a pre-arranged supply depot.

Eight months later, a search party found the tent, the bodies and Scott’s diary. The bodies were buried under the tent, with a cairn of ice and snow to mark the spot.

I sat with my back to the dogs, looking aft, and was enjoying the brisk drive. Then suddenly the surface by the side of the sledge dropped perpendicularly, and showed a yawning black abyss, large enough to have swallowed us all, and a little more. A few inches more to one side, and we should have taken no part in the Polar journey.

– Roald Amundsen (6 July 1872 – c. 18 June 1928), South Pole Expedition – 1910-1912

Each of the other three sledges had a sledge-meter and compass. We were thus equipped with three sledge-meters and four compasses. The instruments we carried were two sextants and three artificial horizons — two glass and one mercury — a hypsometer for measuring heights, and one aneroid.

For meteorological observations, four thermometers. Also two pairs of binoculars. We took a little travelling case of medicines from Burroughs Wellcome and Co. Our surgical instruments were not many : a dental forceps and — a beard-clipper. Our sewing outfit was extensive. We carried a small, very light tent in reserve ; it would have to be used if any of us were obliged to turn back. We also carried two Primus lamps. Of paraffin we had a good supply : twenty- two and a half gallons divided among three sledges. We kept it in the usual cans, but they proved too weak; not that we lost any paraffin, but Bjaaland had to be constantly soldering to keep them tight. We had a good soldering outfit. Every man carried his own personal bag, in which he kept reserve clothing, diaries and observation books. We took a quantity of loose straps for spare ski-bindings. We had double sleepingbags for the first part of the time ; that is to say, an inner and an outer one. There were five watches among us, of which three were chronometer watches.

We took our reindeer-skin clothing, for which we had had no use as yet, on the sledges. We were now

coming on to the high ground, and it might easily happen that it would be a good thing to have. We did

not forget the temperature of — 40° F. that Shackleton had experienced in 88° S., and if we met with the same, we could hold out a long while if we had the skin clothing. Otherwise, we had not very much in our

bags. The only change we had with us was put on here, and the old clothes hung out to air. We reckoned

that by the time we came back, in a couple of months, they would be sufficiently aired, and we could put them on again. As far as I remember, the calculation proved correct. We took more foot-gear than anything else ; if one’s feet are well shod, one can hold out a long time.

By this time the dogs had already begun to be very voracious. Everything that came in their way dis-

appeared ; whips, ski-bindings, lashings, etc., were regarded as delicacies. If one put down anything for a

moment, it vanished. With some of them this voracity went so far that we had to chain them.

Bjaaland astonished me at dinner that day. Speeches had not hitherto been a feature of this journey, but now Bjaaland evidently thought the time had come, and surprised us all with a really fine oration. My amazement reached its culmination when, at the conclusion of his speech, he produced a cigar-case full of cigars and offered it round. A cigar at the Pole !

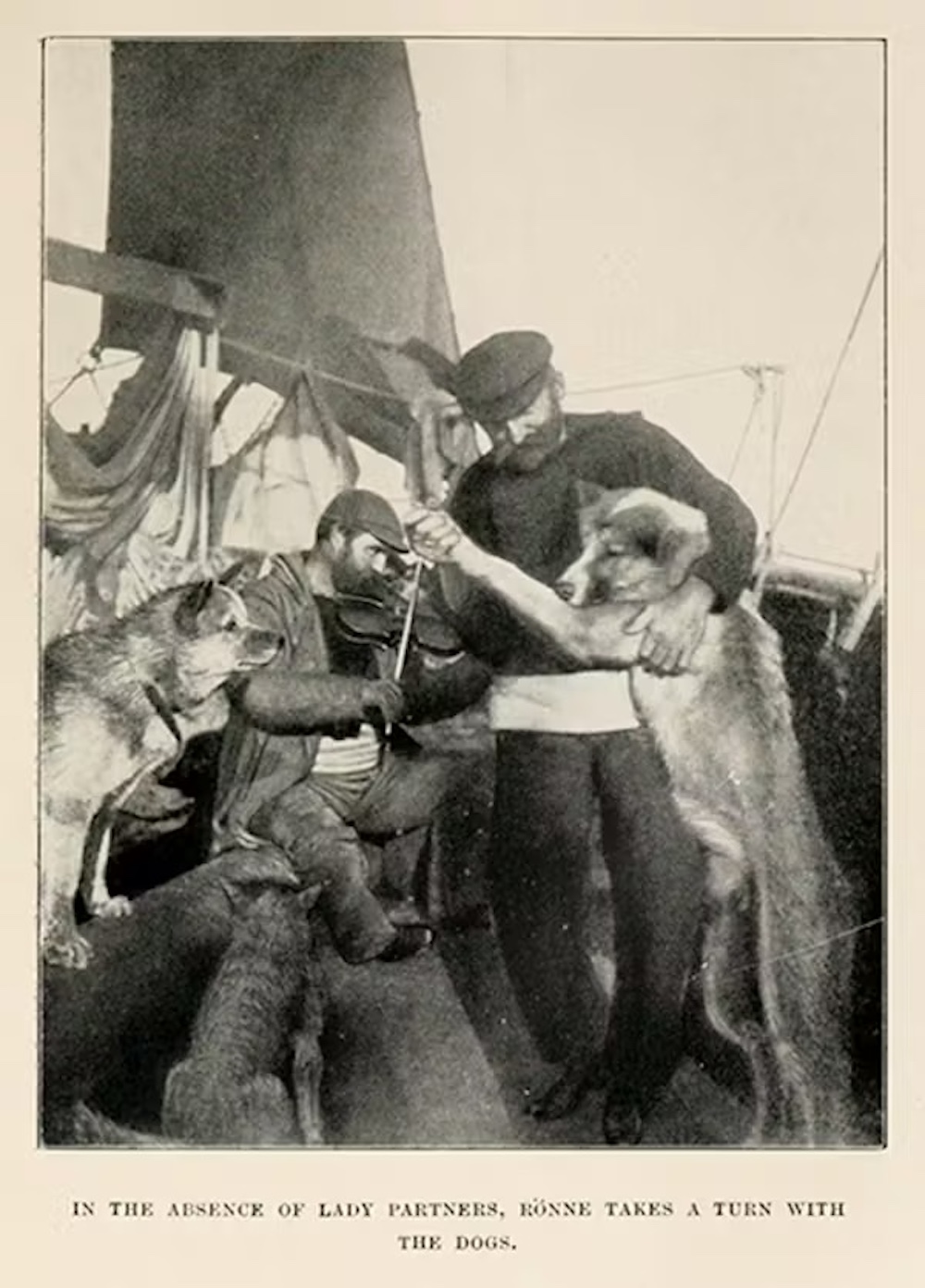

When this festival dinner at the Pole was ended, we began our preparations for departure. First we set up the little tent we had brought with us in case we should be compelled to divide into two parties. It had been made by our able sailmaker, Ronne, and was of very thin windproof gabardine. Its drab colour made it easily visible against the white surface. Another pole was lashed to the tent-pole, making its total height about 13 feet. On the top of this a little Norwegian flag was lashed fast, and underneath it a pennant, on which ” Fram ” was painted.

The tent was well secured with guy-ropes on all sides. Inside the tent, in a little bag, I left a letter, addressed to H.M. the King, giving information of what we had accomplished. The way home was a long one, and so many things might happen to make it impossible for us to give an account of our expedition. Besides this letter, I wrote a short epistle to Captain Scott, who, I assumed, would be the first to find the tent.

Other things we left there were a sextant with a glass horizon, a hypsometer case, three reindeer-

skin foot-bags, some kamiks and mits.When everything had been laid inside, we went into the tent, one by one, to write our names on a tablet we had fastened to the tent-pole. On this occasion we received the congratulations of our companions on the successful result, for the foil owing messages were written on a couple of strips of leather sewed to the tent : “Good luck,” and ” Welcome to 90°,” These good wishes, which we suddenly discovered, put us in very good spirits. They were signed by Beck and Ronne. They had good faith in us. When we had finished this we came out, and the tent-door was securely laced together, so that there was no danger of the wind getting a hold on that side.

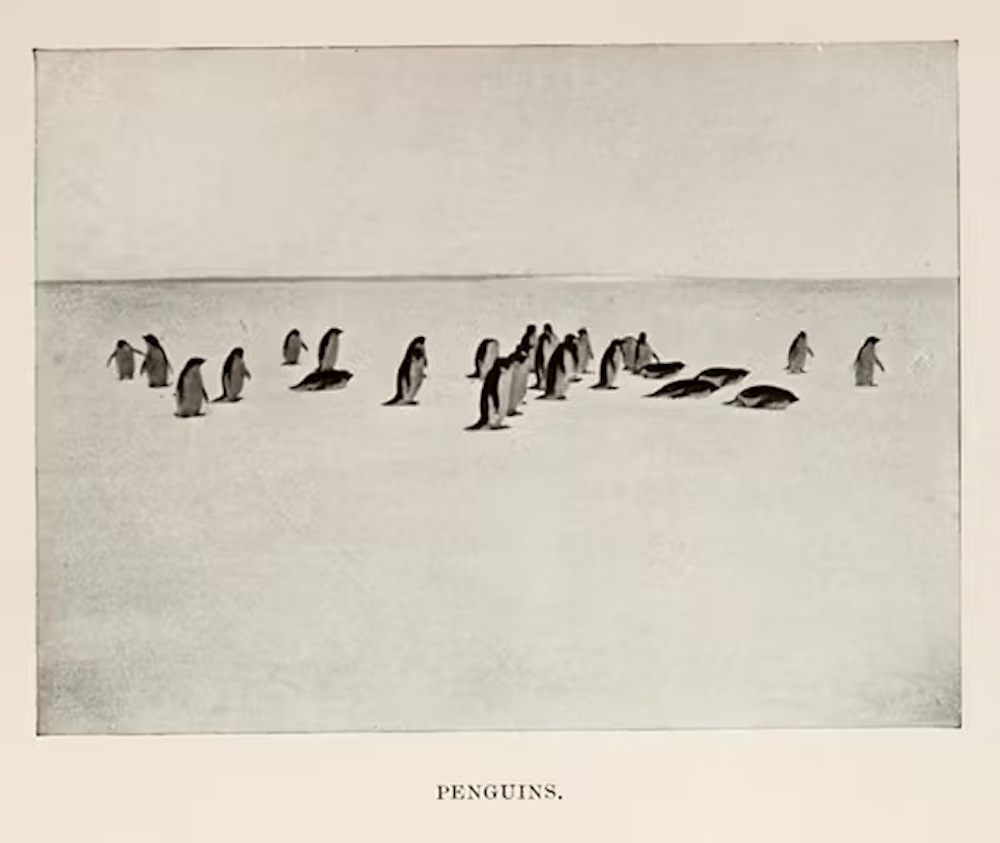

We found the penguins as amusing as the seals were useful. So much has been written recently about these remarkable creatures, and they have been photographed and cinematographed so many times, that everyone is acquainted with them. Nevertheless, anyone who sees a living penguin for the first time will always be attracted and interested, both by the dignified Emperor penguin, with his three feet of stature, and by the bustling little Adelie.

(It turned out that the Adelie penguin is not everyone’s idea of a paragon of fun and laughs, something you can read about in Notes on the Sexual Habits of the ‘Astonishingly Depraved’ Adélie Penguin, 1911.)

We, too, had our share of the seal, and from this time forward we had fresh seal-steak for breakfast at least every day ; it tasted excellent to us, who for nearly half a year had been living on nothing but tinned meat. With the steak whortleberries were always served, which of course helped to make it appreciated. The biggest seal we got in the pack-ice was about 12 feet long, and weighed nearly half a ton.

A few penguins were also shot, mostly Adelie penguins ; these are extraordinarily amusing, and as inquisitive as an animal can be. When any of them saw us, they at once came nearer to get a better view of the unbidden guests. If they became too impertinent, we did not hesitate to take them, for their flesh, especially the liver, was excellent.

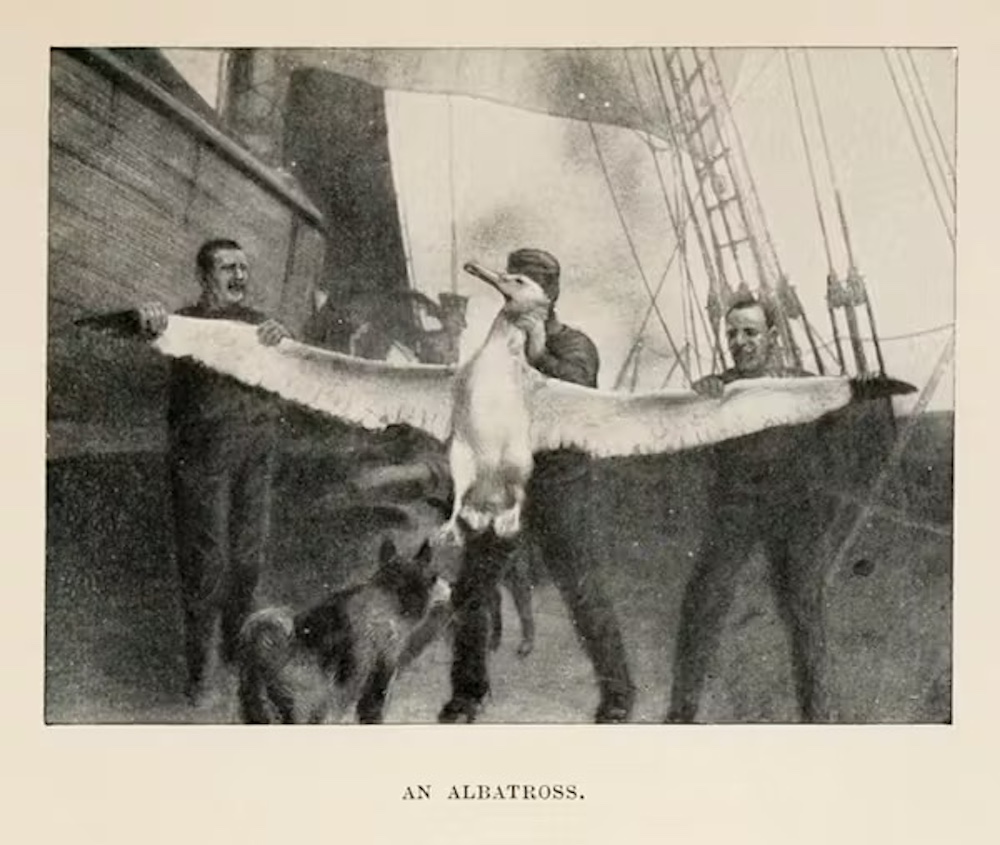

The albatrosses, which had followed us through the whole of the west wind belt, had now departed, and in their place came the beautiful snowy petrels and Antarctic petrels.

In conclusion I will give one or two data. Since the Fram left Christiania on June 7, 1910, we have been two and a half times round the globe ; the distance covered is about 54,400 nautical miles ; the lowest reading of the barometer during this time was 27’56 inches (700 millimetres) in March, 1911, in the South Pacific, and the highest 30*82 inches (783 millimetres) in October, 1911, in the South Atlantic.

On June 7, 1912, the second anniversary of our leaving Christiania, all the members of the Expedition, except the Chief and myself, left for Norway, and the first half of the Expedition was thus brought to a fortunate conclusion.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.