‘The most deadly pestilence would have carried far less terror to the heart than the astronomical prediction on every tongue; it would have made fewer victims, for already, from some unknown cause, the death-rate was increasing. At every instant one felt the electric shock of a terrible fear.’

– Camille Flammarion, Omega: The Last Days of the World (French: La Fin du monde) 1894

Apocalyptic visions are nothing new. The end of the world has long been nigh. And in 1893, the world was ending once more. French author and scientist Camille Flammarion (1842–1925) shared his vision in La Fin du Monde, a book that appeared in English a year later as Omega: The Last Days of the World (1894).

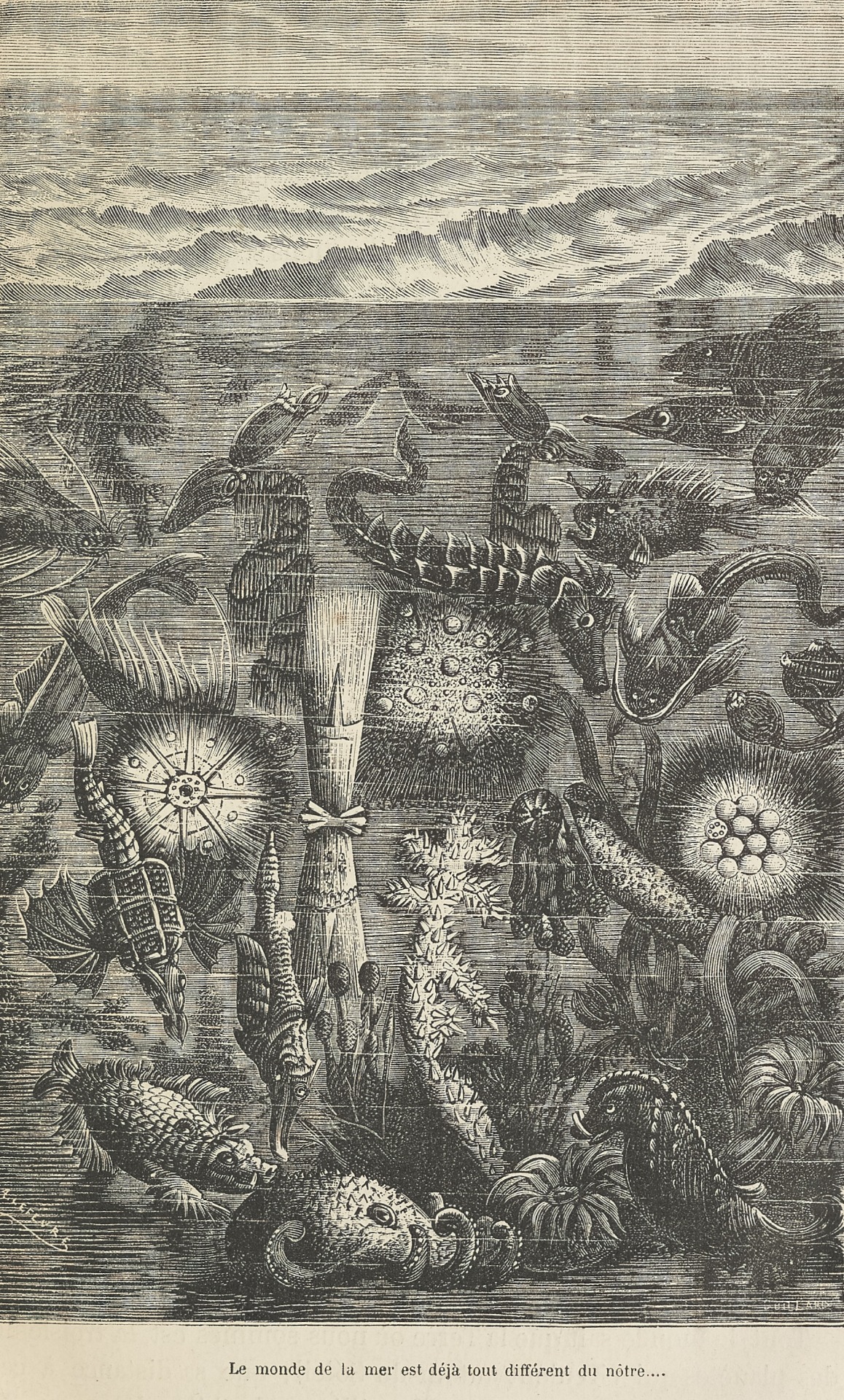

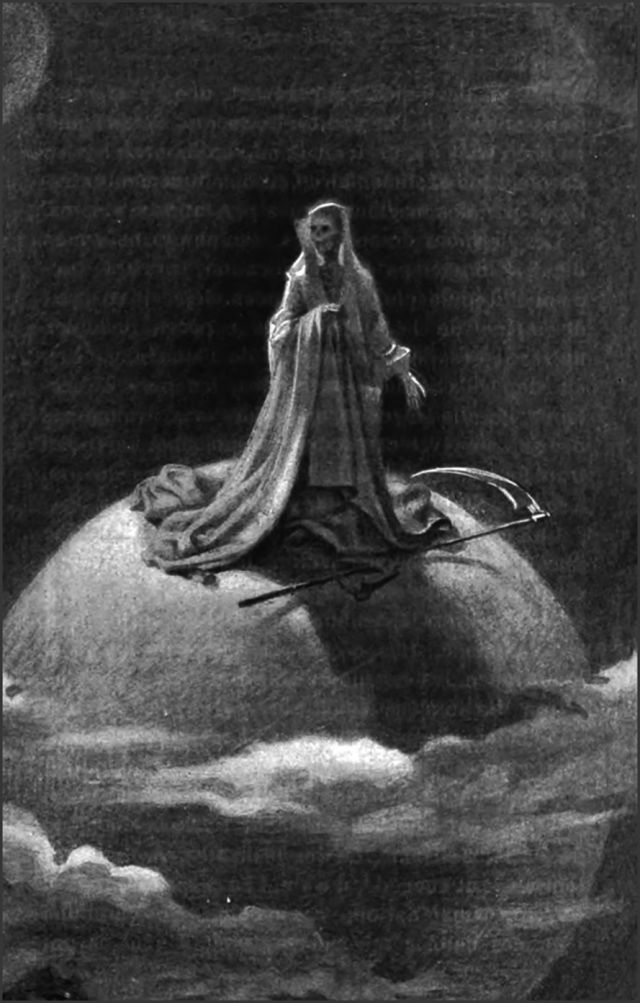

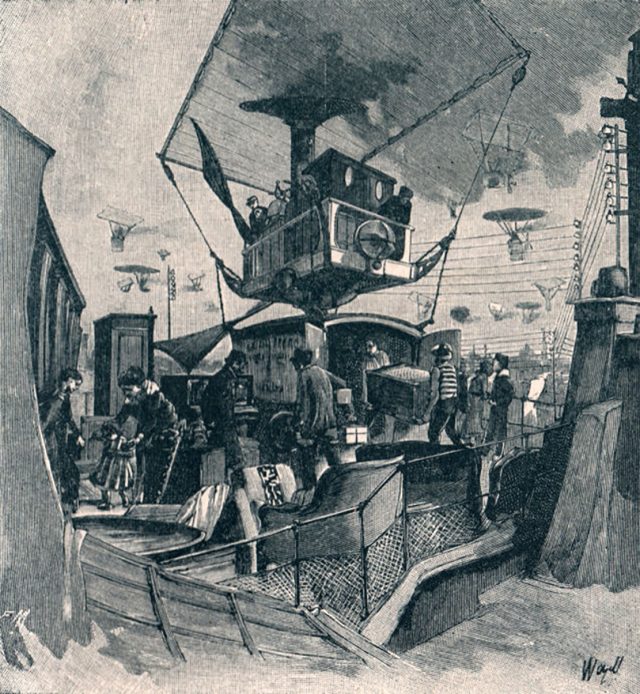

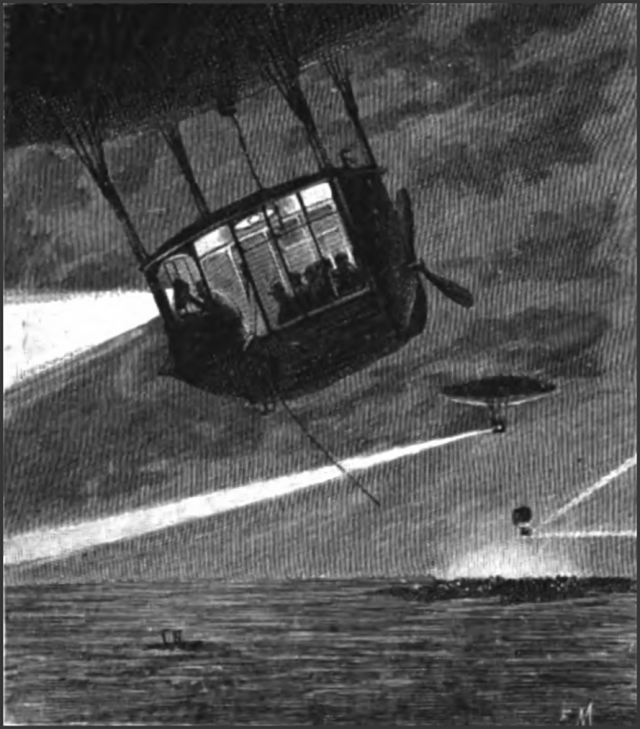

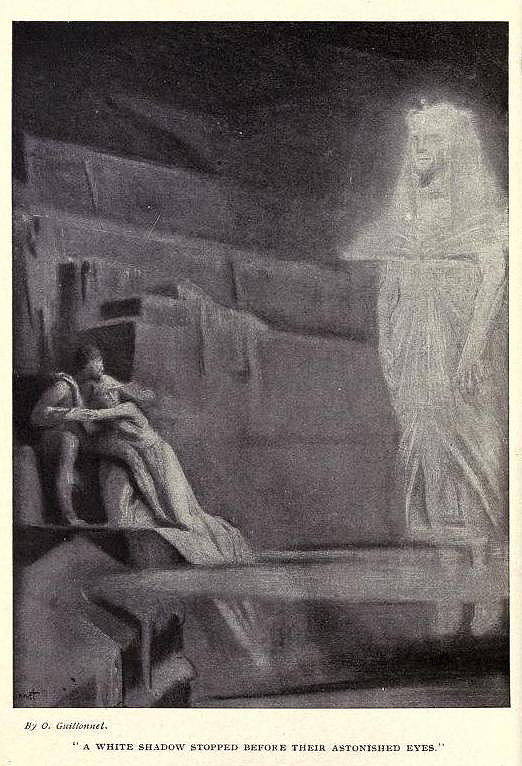

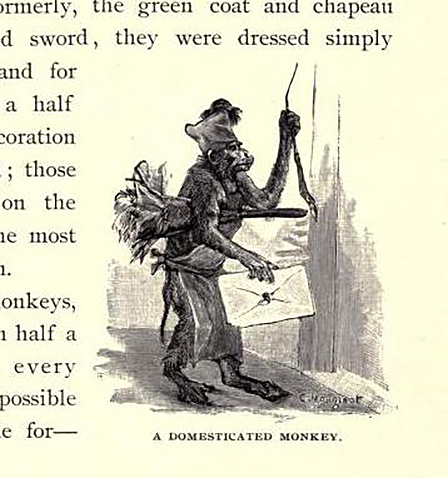

The book is richly enlivened with fabulous illustrations by Jean Paul Laurens, Saunier, Meaulle, Vogel and others. The opening illustration (above) of death atop the world borrows from Dreams No Mortal Ever Dared to Dream Before by Gustave Doré, from 1884.

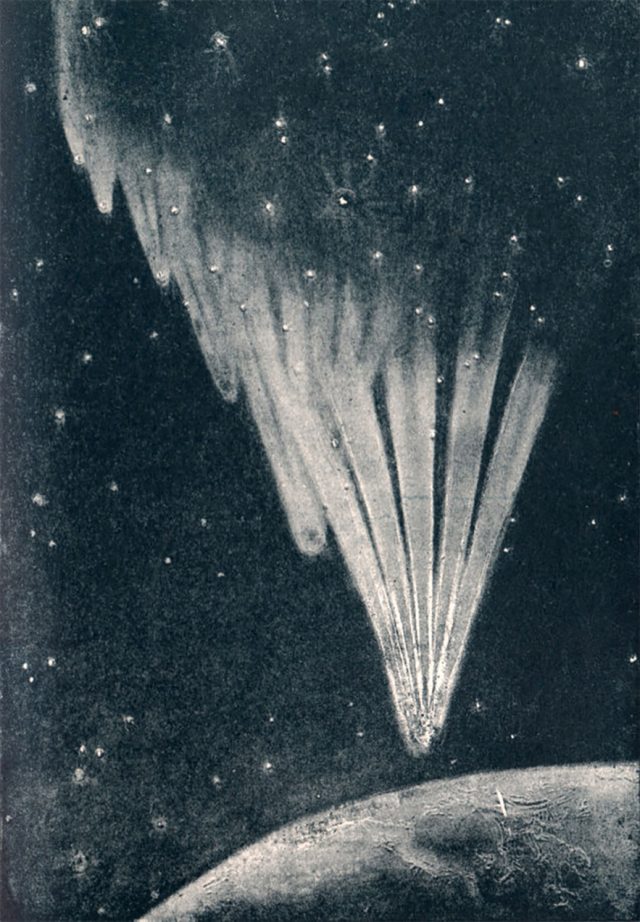

Flammarion’s story of the end begins in the 25th century, when a comet made mostly of Carbonic-Oxide (CO) is seemingly on a collision course with Earth. After mass panic and lots of scientific calculations, the comet 30 times the size of Earth passes us by. But things are changed. The consequences of the cosmic event are far-reaching, setting in motion a series of physical, psychic and social changes that will profoundly affect the planet and humanity far into the future. And once more death awaits.

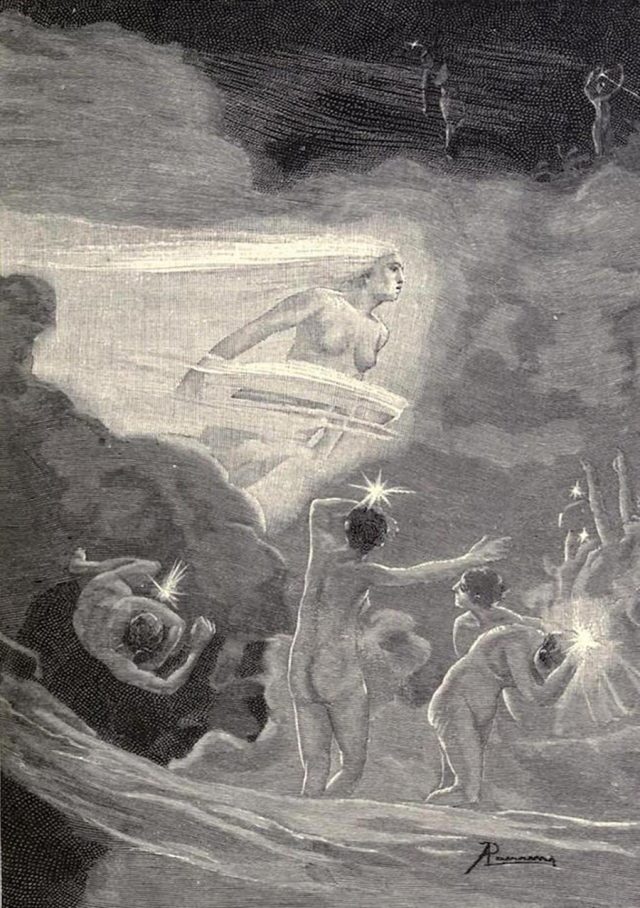

After that near miss, readers are cast to the 100th century AD. Humanity has altered into a harmony of the electric and psychical. Millions of years pass. The sun begins to fade and cool. The Earth becomes frozen. Only two humans remain: Omegar and Eva. This Adam and Eve redux accept their fate.

But there is hope. The spirit world intervenes and the pair are transported to Jupiter, where they find more humans. All good, then, But no. The entire solar system is dying, so too the cosmos. But this is regeneration. It turns out that death needed to make space for new planets, stars and possibilities.

A fitting tale by a man described as an “astronomer, mystic and storyteller” who was “obsessed by life after death, and on other worlds, and [who] seemed to see no distinction between the two”. He was convinced that souls after the physical death pass from planet to planet and progressively improve at each new incarnation.

To Flammarion, we are each of us a “citizen of the sky” in search of other worlds, “studios of human work, schools where the expanding soul progressively learns and develops, assimilating gradually the knowledge to which its aspirations tend, approaching thus evermore the end of its destiny.”

As he adds: “And these universes passed away in their turn. But infinite space remained, peopled with worlds, and stars, and souls, and suns; and time went on forever. For there can be neither end nor beginning.”

Camille Flammarion

Camille Flammarion (26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He published his first book in 1862, La pluralité des mondes habités (The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds) and went on to write more than fifty more, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and works on psychical research and related topics. He also published the magazine L’Astronomie, starting in 1882. An avid stargazer, he maintained a private observatory at Juvisy-sur-Orge, France.

For him, the sky spoke of unity and oneness:

“What intelligent being, what being capable of responding emotionally to a beautiful sight, can look at the jagged, silvery lunar crescent trembling in the azure sky, even through the weakest of telescopes, and not be struck by it in an intensely pleasurable way, not feel cut off from everyday life here on earth and transported toward that first stop on the celestial journeys? What thoughtful soul could look at brilliant Jupiter with its four attendant satellites, or splendid Saturn encircled by its mysterious ring, or a double star glowing scarlet and sapphire in the infinity of night, and not be filled with a sense of wonder? Yes, indeed, if humankind — from humble farmers in the fields and toiling workers in the cities to teachers, people of independent means, those who have reached the pinnacle of fame or fortune, even the most frivolous of society women — if they knew what profound inner pleasure await those who gaze at the heavens, then France, nay, the whole of Europe, would be covered with telescopes instead of bayonets, thereby promoting universal happiness and peace.”

— Camille Flammarion, 1880

The Illustrated Flammarion

Camille Flammarion’s books were heavy on illustrations, many of them wonderful. Here are a few more highlights:

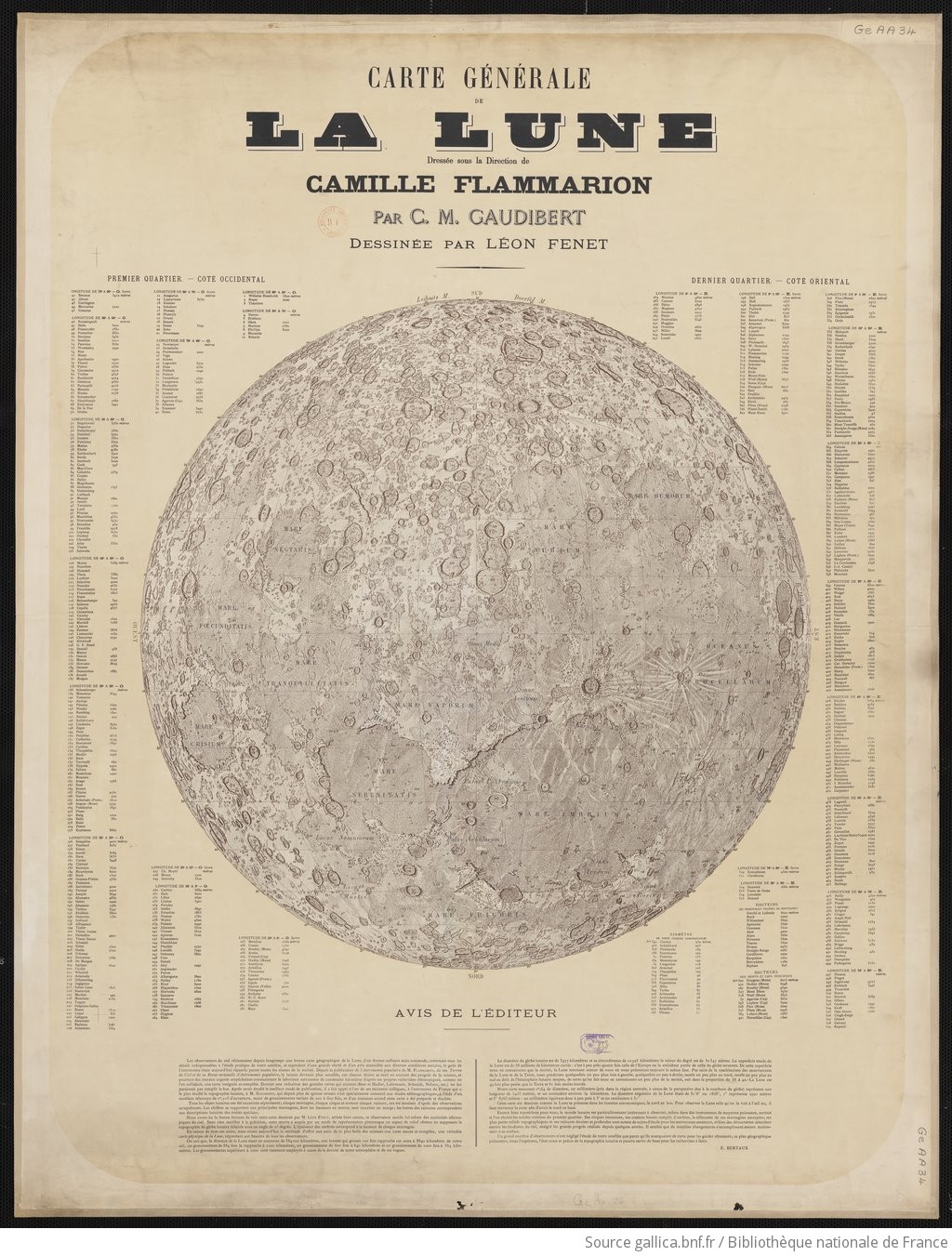

Carte générale de la lune / dressée sous la direction de Camille Flammarion ; par C.-M. Gaudibert ; dessinée par Léon Fenet

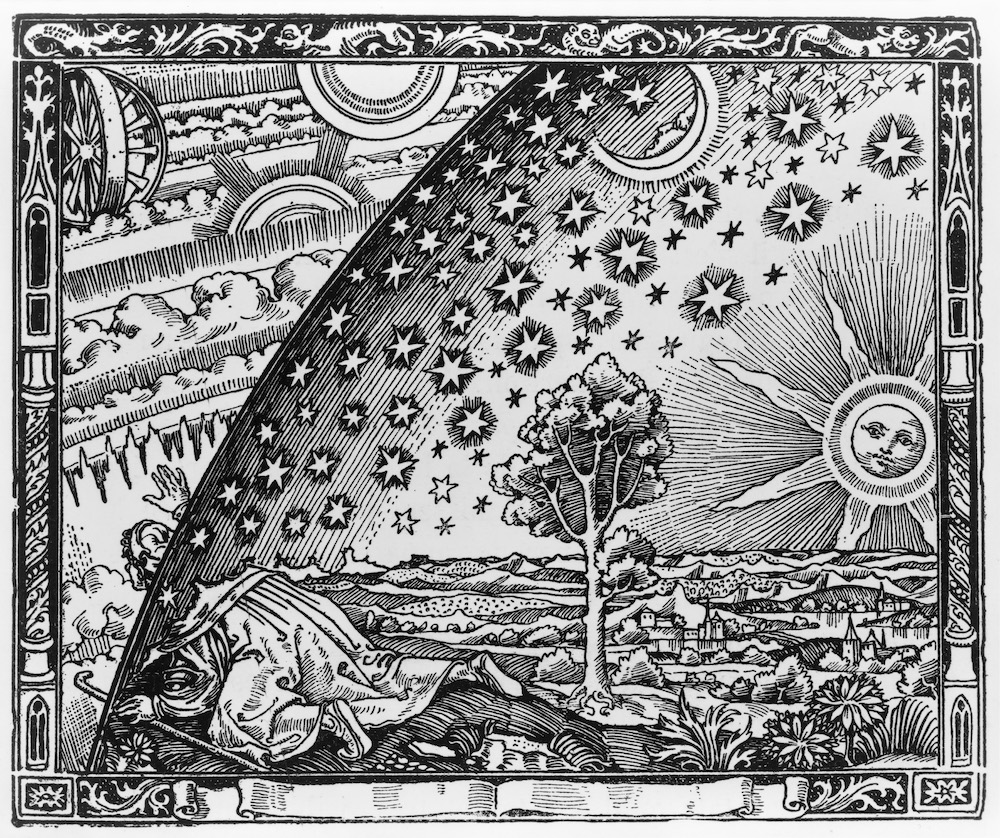

The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in Camille Flammarion’s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888). The image depicts a man crawling under the edge of the sky, depicted as if it were a solid hemisphere, to look at the mysterious Empyrean beyond. The caption translates to “A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet…”

More space stories here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.