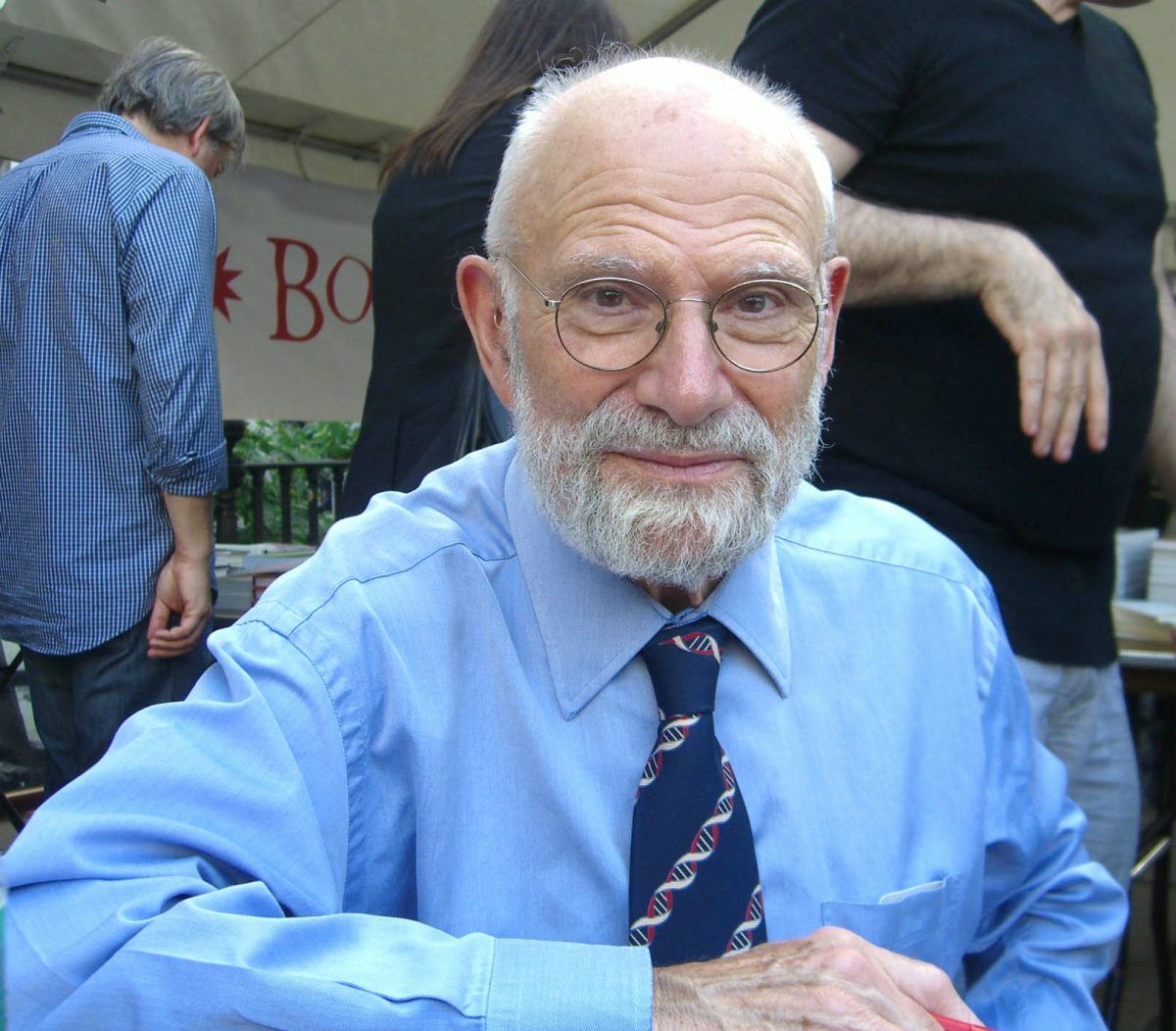

“Each of us … constructs and lives a ‘narrative’ and is defined by this narrative … I suspect that a feeling for stories, for narrative, is a universal human disposition, going with our powers of language, consciousness of self, and autobiographical memory.”

– Oliver Sacks, the writer and neurologist whose writing gave insight to his intense sensitivity to the perspectives of others.

Oliver Sacks (July 9, 1933–August 30, 2015) had a lifelong love of books. Sacks was the best-selling author and neurologist who wrote about the brain’s quirks in his books and essays, using case histories as “neurological novels”. Through him we are now familiar with conditions like Tourette’s and Asperger’s. We get to see people anew, as Sacks saw blind Madeleine J., who perceived her hands only as “lumps of dough”; and Dr. P., whose story inspired the book The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat – his brain unable to decipher what his eyes were seeing.

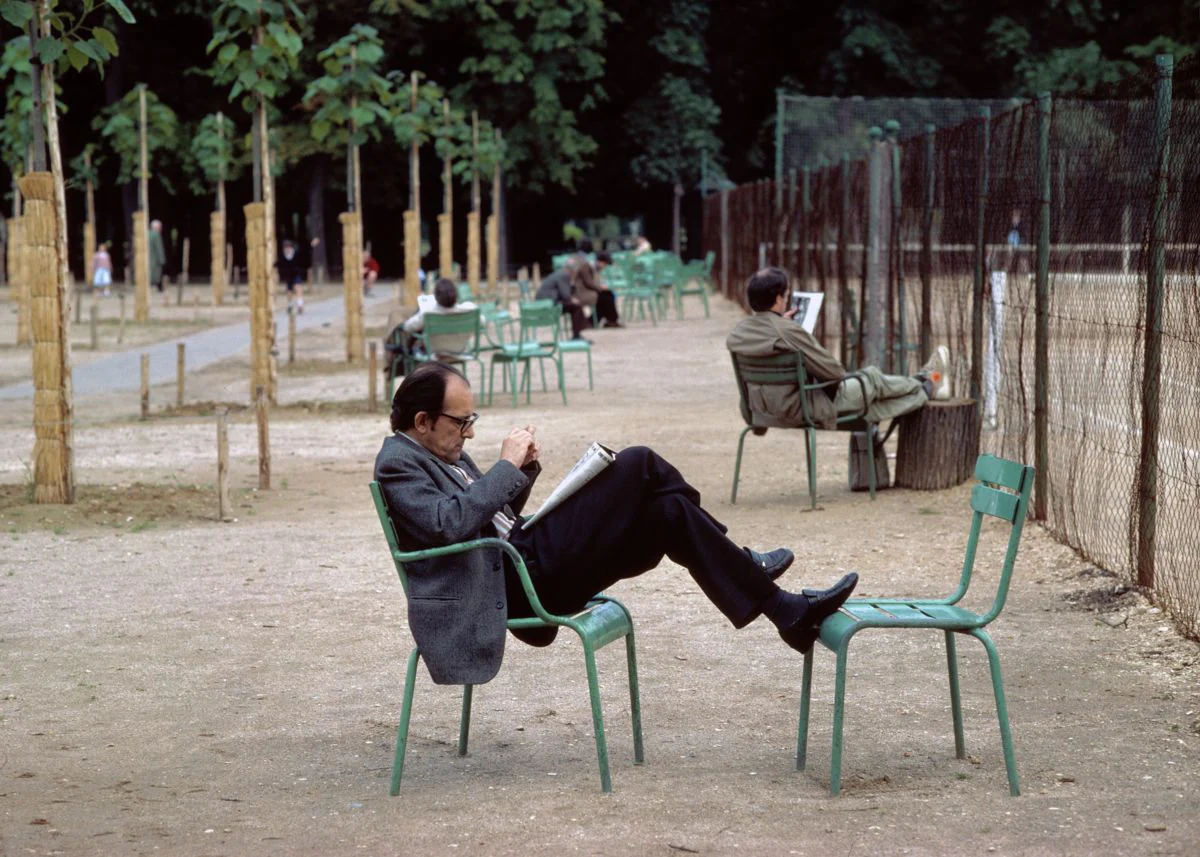

Sacks was shy in ordinary social contexts and affected by indifferent eyesight and hearing loss. “I tend to retreat into a corner, to look invisible, to hope I am passed over,” he wrote in his 2015 autobiography On the Move: A Life. (previously). Reading was his escape into other worlds. He read widely – biographies of leading scientists, books on philosophy and poetry, Hebrew books, plays and inherited books in his family’s home library.

Away from home he read more at the Willesden Public Library in north London, a short walk from the family home. “It was deceptively small outside, but vast inside, with dozens of alcoves and bays full of books,” Sacks wrote, “more books than I had ever seen in my life. Once the librarian was assured I could handle the books and use the card index, she gave me the run of the library and allowed me to order books from the central library and even sometimes to take rare books out. My reading was voracious but unsystematic: I skimmed, I hovered, I browsed, as I wished…”

But there was one book that he prized above all others. And thanks to his talent (and five pints of cider) he got to own the complete Oxford English Dictionary:

My mother, a surgeon and anatomist, while accepting that I was too clumsy to follow in her footsteps as a surgeon, expected me at least to excel in anatomy at Oxford. We dissected bodies and attended lectures and, a couple of years later, had to sit for a final anatomy exam. When the results were posted, I saw that I was ranked one from bottom in the class. I dreaded my mother’s reaction and decided that, in the circumstances, a few drinks were called for. I made my way to a favorite pub, the White Horse in Broad Street, where I drank four or five pints of hard cider—stronger than most beer and cheaper, too.

Rolling out of the White Horse, liquored up, I was seized by a mad and impudent idea. I would try to compensate for my abysmal performance in the anatomy finals by having a go at a very prestigious university prize — the Theodore Williams Scholarship in Human Anatomy. The exam had already started, but I lurched in, drunkenly bold, sat down at a vacant desk, and looked at the exam paper.

There were seven questions to be answered; I pounced on one (“Does structural differentiation imply functional differentiation?”) and wrote nonstop for two hours on the subject, bringing in whatever zoological and botanical knowledge I could muster to flesh out the discussion. Then I left, an hour before the exam ended, ignoring the other six questions.

The results were in The Times that weekend; I, Oliver Wolf Sacks, had won the prize. Everyone was dumbfounded — how could someone who had come one but last in the anatomy finals walk off with the Theodore Williams prize? I was not entirely surprised, for it was a sort of repetition, in reverse, of what had happened when I took the Oxford prelims. I am very bad at factual exams, yes-or-no questions, but can spread my wings with essays.

Fifty pounds came with the Theodore Williams prize — £50! I had never had so much money at once. This time I went not to the White Horse but to Blackwell’s bookshop (next door to the pub) and bought, for £44, the twelve volumes of the Oxford English Dictionary, for me the most coveted and desirable book in the world. I was to read the entire dictionary through when I went on to medical school, and I still like to take a volume off the shelf, now and then, for bedtime reading.

More books, authors and reading in the archive.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.