In the summer of 1962, Danny Lyon packed a Nikon Reflex and an old Leica in an army bag and hitchhiked south. Within a week he was in jail in Albany, Georgia, looking through the bars at another prisoner, Martin Luther King Jr. Lyon soon became the first staff photographer for the Atlanta-based Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which already had a reputation as one of the most committed and confrontational groups fighting for civil rights.

“This young white New Yorker came South with a camera and a keen eye for history. And he used these simple, elegant gifts to capture the story of one of the most inspiring periods in America’s twentieth century.” — John Lewis, US congressman.

It was the summer of 1962, writes Danny Lyon. I had just finished my third year at the University of Chicago. My 650cc Triumph motorcycle was damaged, leaving me grounded and bored. One of my classmates, Linda Pearlstein, had been arrested in civil rights demonstrations in Cairo, Illinois. With contacts from Linda, I put my 35 mm Nikon F reflex into an old army bag, asked my sister-in-law to drive me to Route 66 at the city’s edge, stuck out my thumb, and hitchhiked south. I thought I was just going on an adventure.

As the sun set, I stepped into a pay phone booth in East St. Louis and called a number I had received from Linda. I told whoever picked up the phone that I would reach Cairo that night by bus. Cairo is at the confluence of the Mississippi and the Ohio Rivers. It was the free town that Huck and Jim were headed to but floated by in the night. It was Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters when he engineered the capture of Fort Donaldson.

That night, as the bus door swung open at the Greyhound stop in Cairo, a large black man stood on the other side. I was a bit afraid, until from behind him stepped a shorter, white woman. Charles Neblett and Selyn McCollum had both been Freedom Riders, and both worked for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The next morning, in a small black church, I listened to a speech by a local high school student and movement leader, Charles Kohn. In the corner sat John Lewis, whom I recognized as a leader of the Freedom Rides. I had been in few churches before, but never in a black church. A New Yorker, the son of a physician and Jewish immigrants, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a black hospital. The trip I was now on would profoundly change my knowledge, my feelings, my prejudices, and my view of everything American.

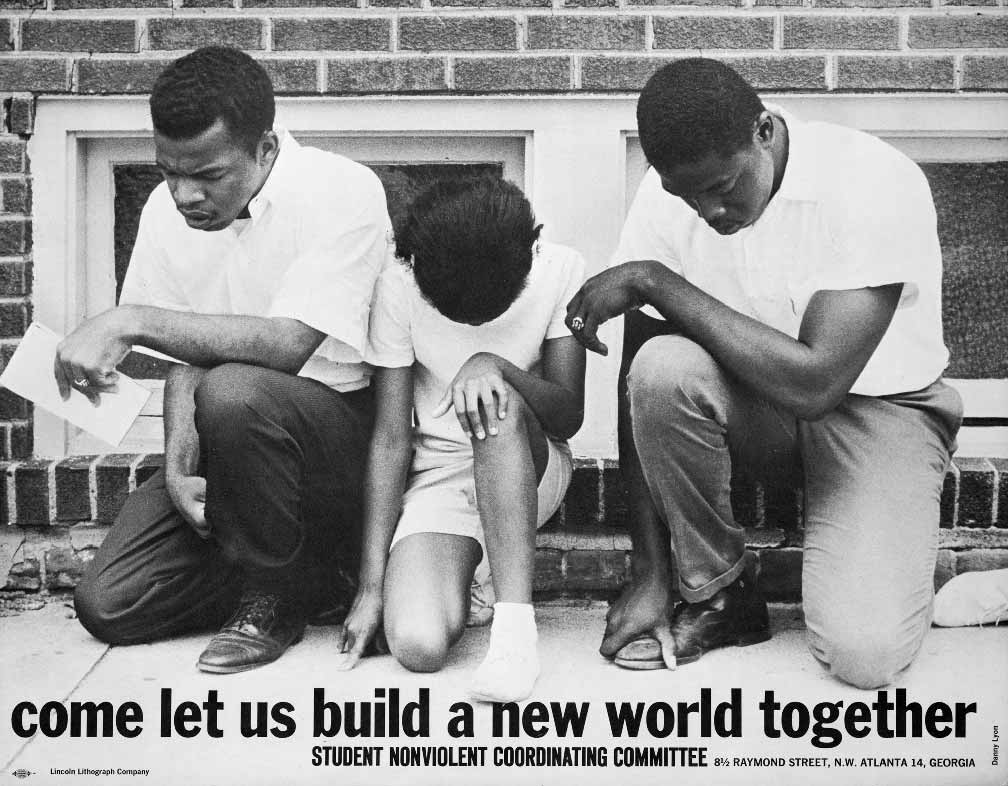

After the service, the small group marched to a segregated swimming pool that sported a “Private Pool, Members Only” sign. Among the pictures I made outside the pool was one of three of the demonstrators kneeling and praying. Perhaps it was the light. Maybe it was the white thugs grinning and cursing at us from the pool door. It struck me as a sublimely beautiful moment: the grace of the three, the two men kneeling at each side, the child in the middle.

John Lewis, left, on a SNCC poster, 1963; photo by Danny Lyon

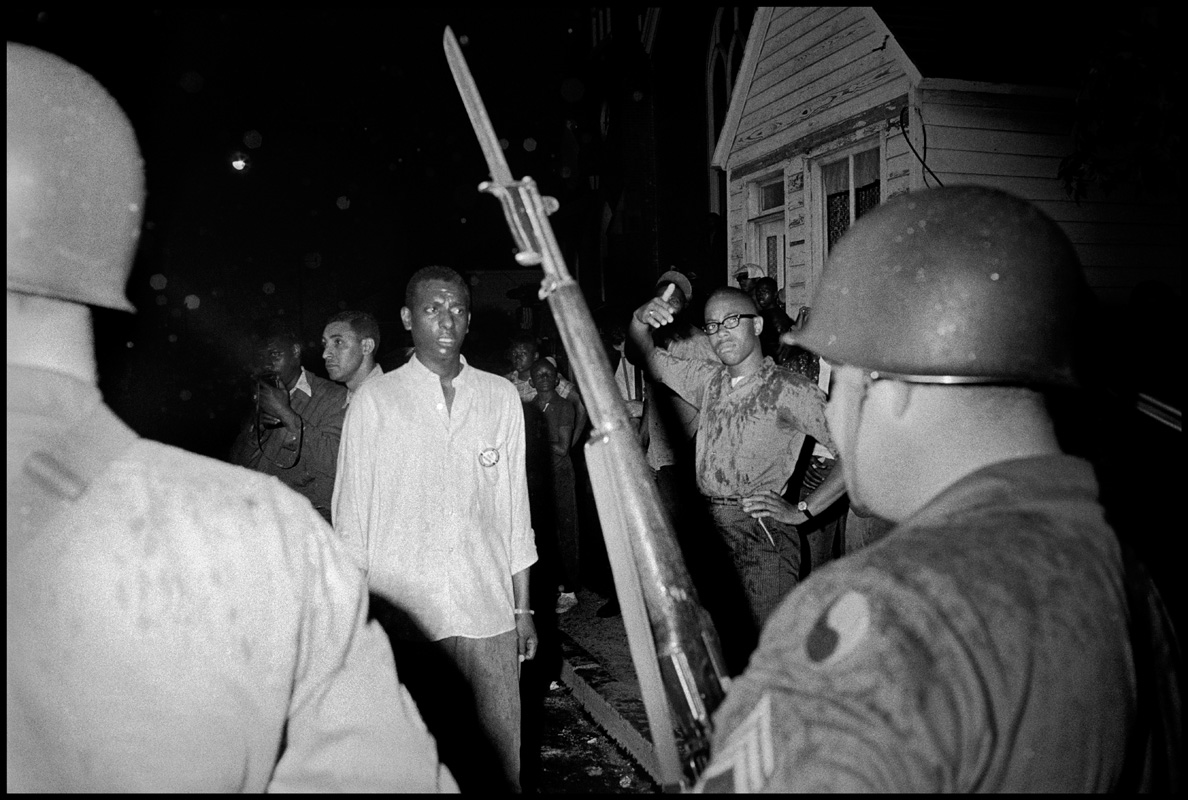

In a few days, with advice and contacts from John, I went on to Nashville, Tennessee, then to the SNCC headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, only to be told by the woman who opened the door that “everybody” was down in Albany. Rather than take a segregated seat on the Atlanta-Albany bus, with whites sitting in front, blacks in the rear, I stood. The only other person standing was a nattily dressed black man who suggested I not try to reach the colored half of town at night. That turned out to be Wyatt Tee Walker, one of Dr. King’s lieutenants. It was a hot and humid night, with bugs flying in the bright lights of the Albany Greyhound station. An overweight policeman stood in front of me as I stepped off the bus.

“That’s nigger town. That’s the white side. Where you going?”

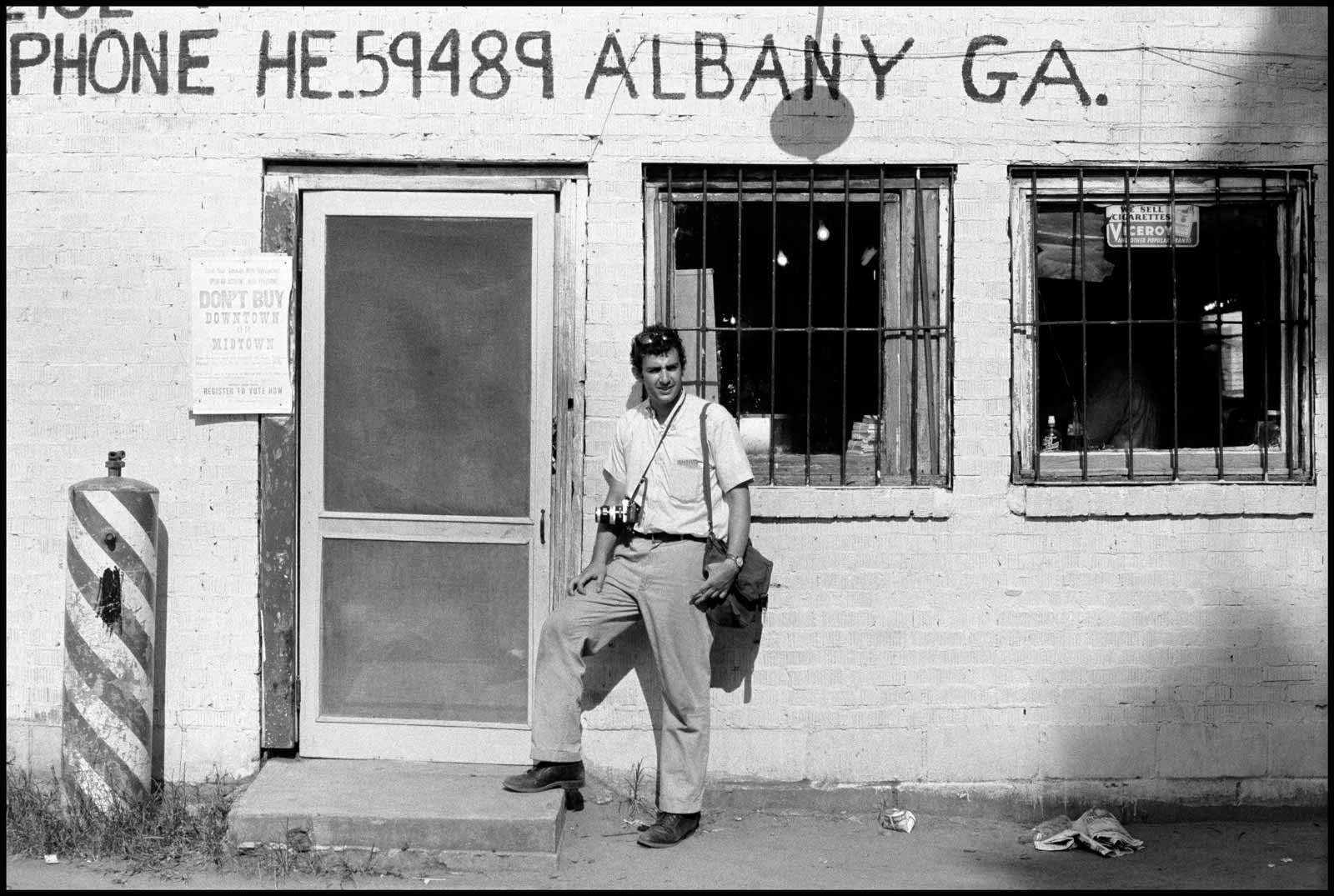

I spent the night at the white YMCA. In the morning, I walked unmolested into the black side of town and proudly had my photograph taken in front of the local SNCC office, a barbershop with a “Don’t Buy Downtown” sign out in front.

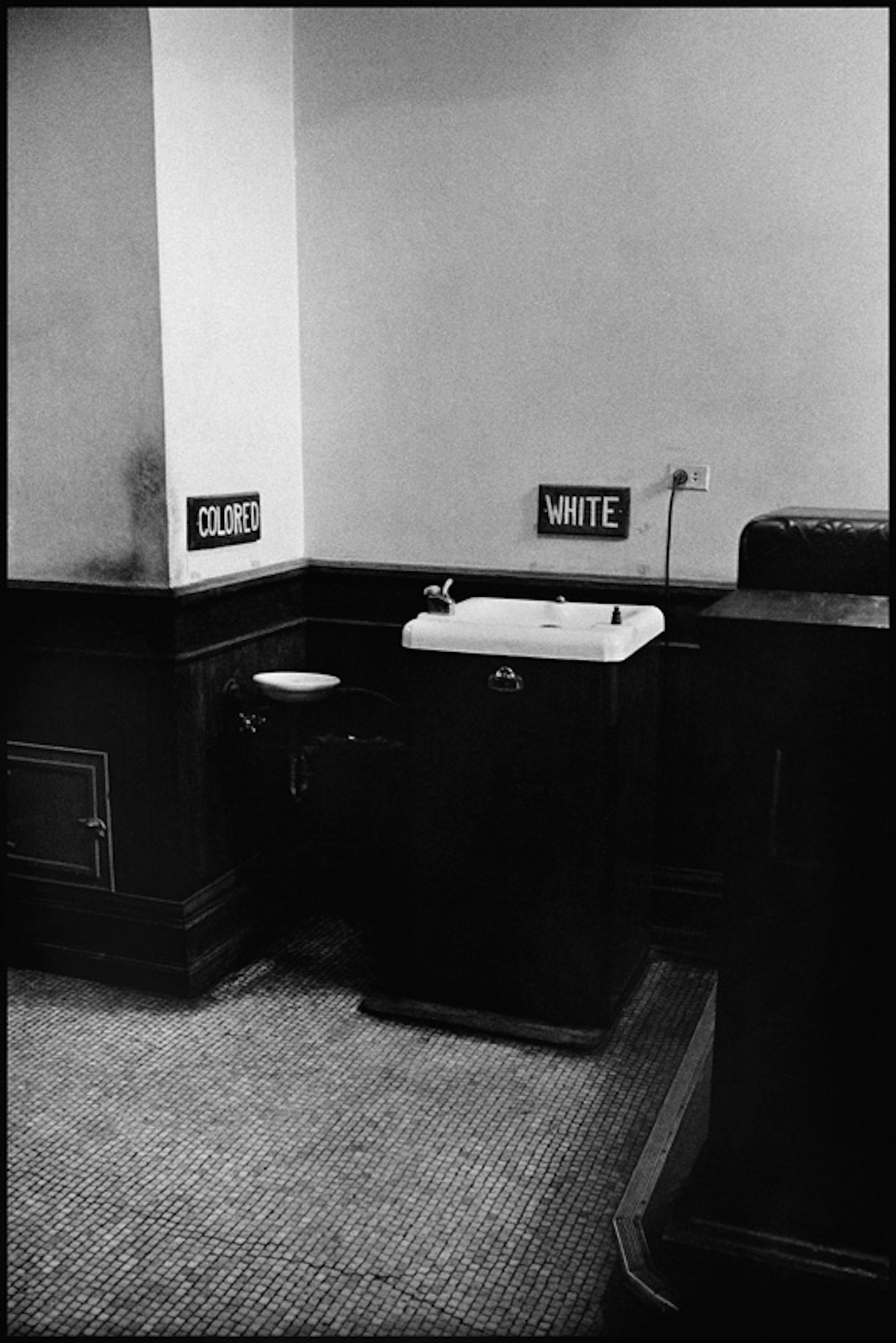

I had done it. Deep in the South I had reached one of the towns central to an uprising that would sweep away legal segregation, bring the vote to black people in the thirteen states that had made up the Confederacy, and overthrow the system of racial oppression called Jim Crow that had been re-imposed in those states after the Civil War. Over my shoulder was a Nikon F reflex. “You got a camera,” James Forman—then SNCC’s executive secretary—said to me when we met at the Freedom House. “Go inside the courthouse. Down at the back they have a big water cooler for whites and next to it a little bowl for Negroes. Go in there and take a picture of that.”

Forman is one of the under-recognized major heroes of the Southern civil rights movement. He would protect me, promote me, and in the coming years become like a father to me. The corridor of the courthouse was dark, and the fountains were way in the back and hard to see. My heart was pounding as I leaned against the wall to make a time exposure, terrified that someone would appear.

After that first night, I stayed in the colored part of town and would venture downtown during the day to make photographs. One was of two SNCC workers being arrested at a drugstore lunch counter. One white from the north, the other a black former gang leader whom SNCC had brought into the movement, they were getting arrested so I could photograph them. That made it easy for me to be standing ready by the police cars and make pictures as they were carried out.

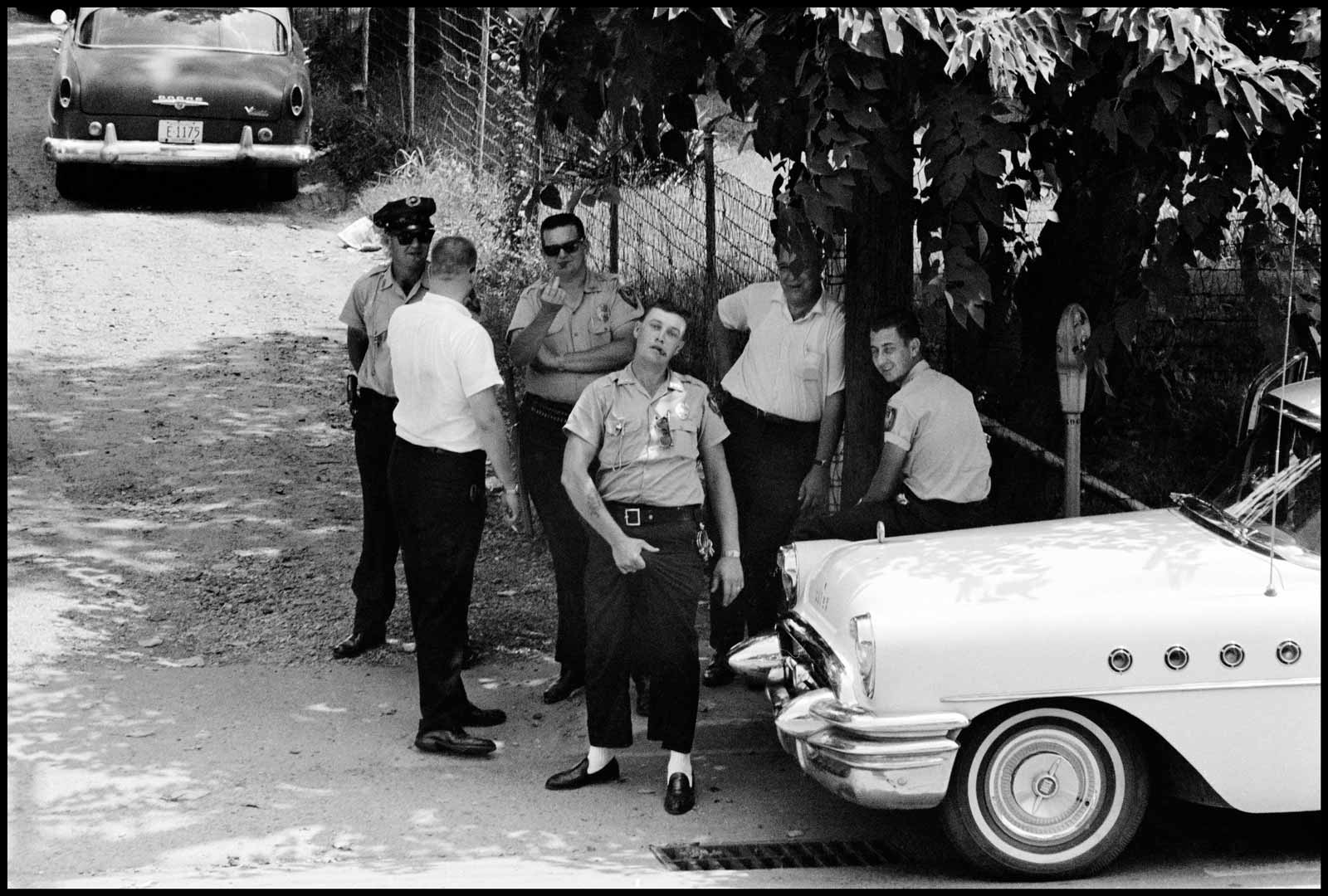

That afternoon at the Freedom House, I met a pretty young white woman and we ended up at a downtown bar, where she proceeded to get drunk and loudly announce that she was married to a black man back home in South Carolina. I found this an unnerving conversation as everyone in the bar could hear her and had begun to stare at us. As we stepped into the street, a few police officers emerged from squad cars to arrest us both. I made a fuss as they confiscated my Nikon before locking me in a cell for the night. Through the bars and across the hall, I could see Dr. King in his cell on the black side of the jail. A day or two after I was released, I had the nerve to return to the jail and take pictures of the exterior. A group of policemen soon surrounded me.

“Who are you?” I’m not sure what I said, but I remember what they said. “You’re shaking now, boy. You’re going to be shaking a lot harder when we’re done with you.”

USA. Birmingham, Alabama. 1963. Members of the Alabama Highway Patrol make a show of force during the morning of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church by the KKK.

Danny Lyon/The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

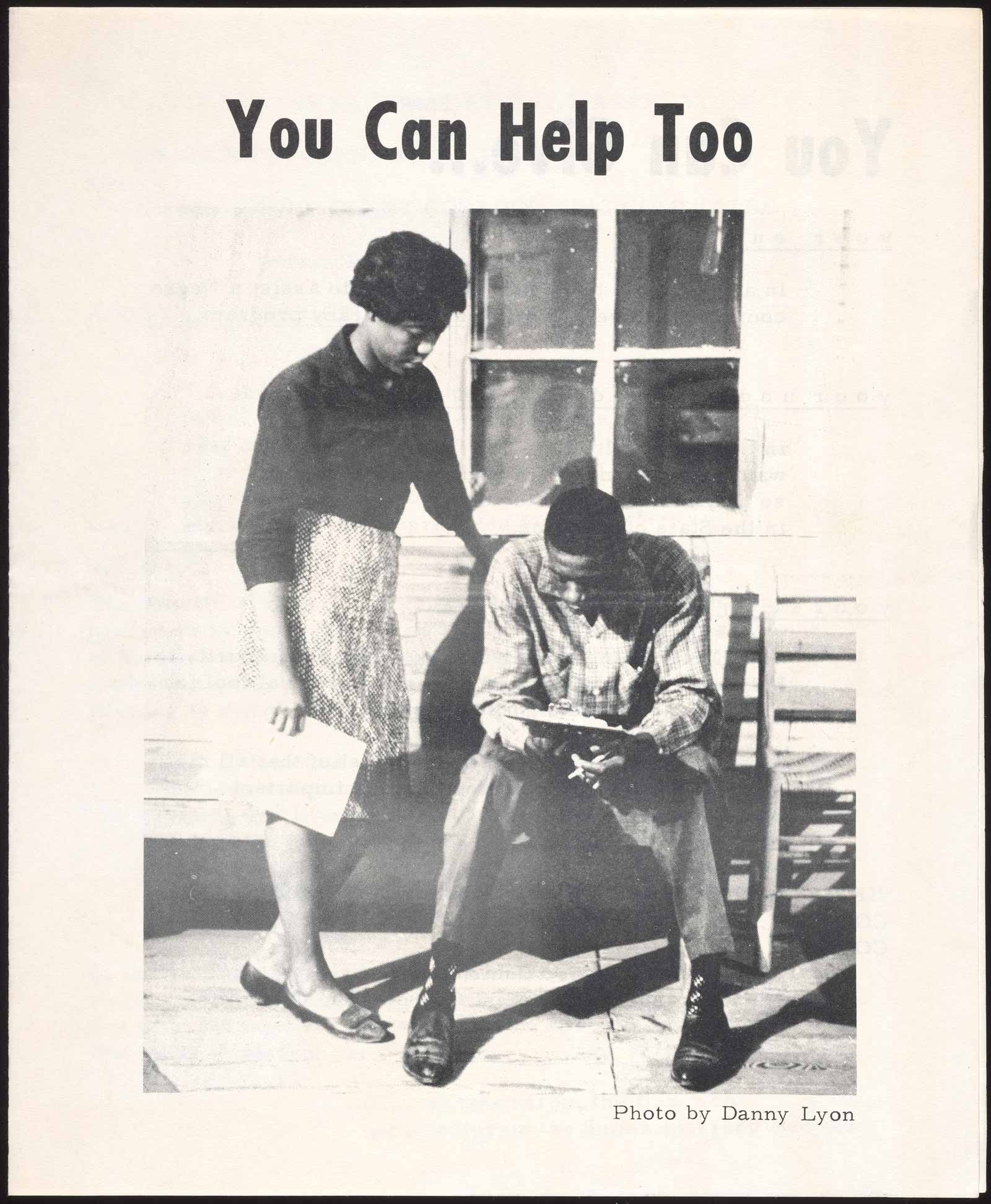

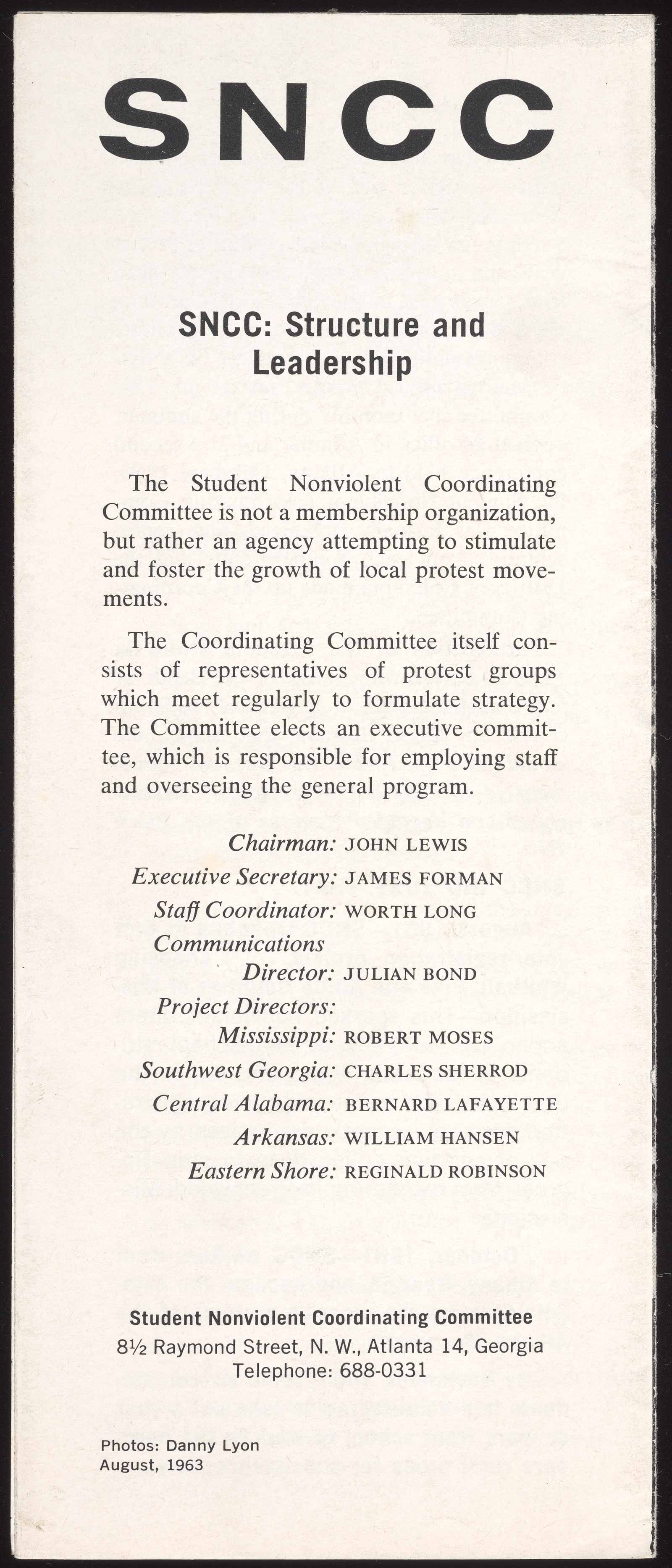

SNCC brochure, 1963

I left town the next morning, heading north and back to school. My pictures and text were published in the University of Chicago student paper, the Maroon. Others were used for fundraising by SNCC. A month later, in September 1962, I made my second trip south. Forman had gone to Harry Belafonte for a $300 check so that I could reach the Mississippi Delta and photograph Bob Moses, who lived in Cleveland at the house of Amzie Moore, a World War II veteran and gas station owner who had invited Moses and SNCC to Mississippi to organize voter registration. Because it was dangerous for blacks to be seen together with whites in cars, or anywhere else, in Mississippi, the office kept white workers out. I was probably one of the first whites to reach SNCC workers in the Delta. It was September and the cotton was in full bloom. I joined Charlie Cobb and Frank Smith and stayed with them in a small house in Ruleville. The wall over my bed was perforated with shotgun holes. Frank had me wear a straw hat because it made me look more “like a cracker.” The field workers took me to a plantation to photograph folks picking cotton.

Then I made one walk downtown too many. As I passed the small cinderblock Cleveland police station, an officer stepped out from the parking lot and pulled me inside. I sat across from the chief as he politely explained to me that “in order to engage in the practice of photography” in Cleveland I needed to post a $1,000 bond. He opened a book of ordinances and pointed to the line. Outside in the parking lot, the policeman who had pulled me in was waiting. Clearly agitated, he explained with deep emotion that “we don’t mix the races down here.” He was sweating and rocking back and forth. Bizarre as it sounds, Frank Smith had told me that if I got into trouble I should just say I was black. This was apparently a common SNCC ruse, but it escaped me that I was supposed to say that it was a black woman who numbered among my recent ancestors. “As a matter of fact,” I said, “my grandfather was colored.” The policeman went completely crazy, reached for the gun on his belt, and said he would kill me right there on the spot. I thought he meant it.

I backed into the street and walked rapidly in the hot sun towards the Freedom House, praying that a car would pass by and pick me up. Within a block, some kids who recognized me from the Freedom House stopped their car, and I yanked open the back door and jumped inside. I left town as soon as I could and headed to Oxford, where James Meredith was trying to enroll as the first black student at Ole Miss (the University of Mississippi).

Danny Lyon/The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

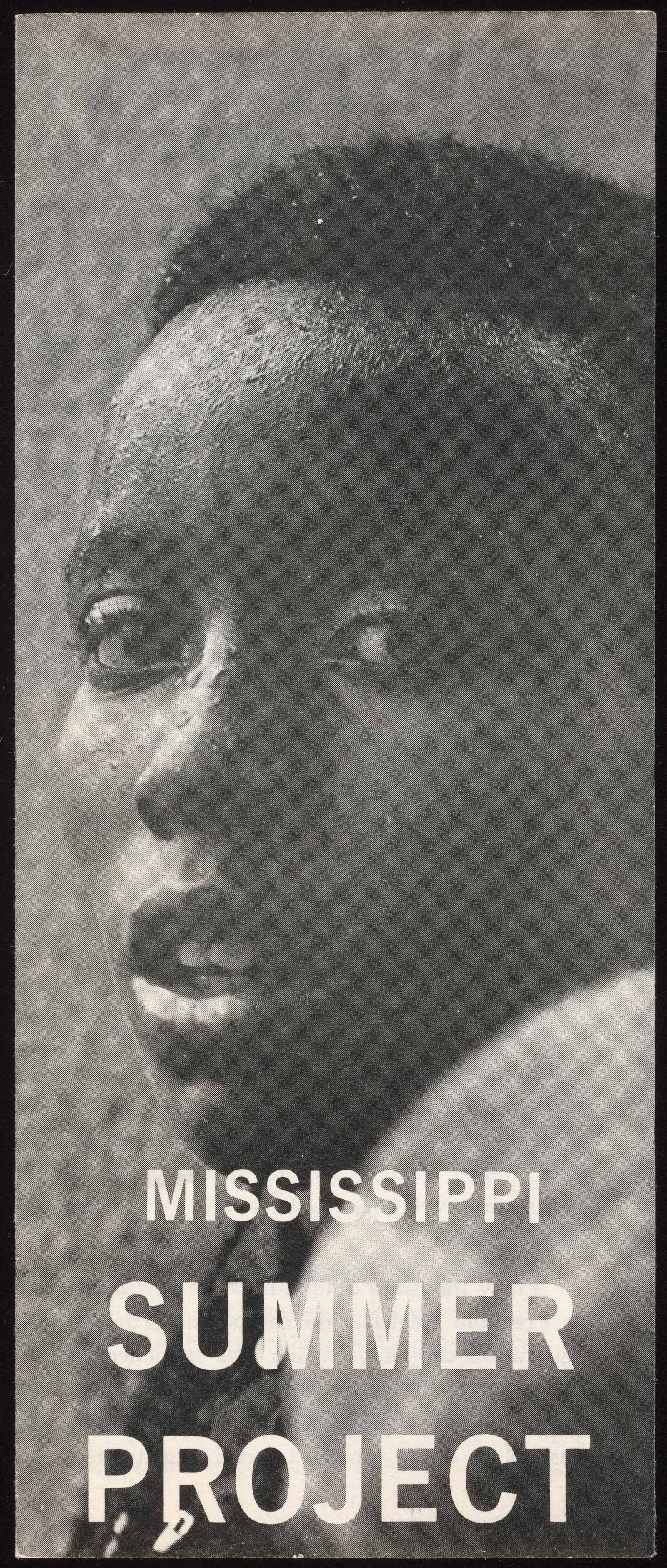

SNCC brochure for Mississippi Summer; photo by Danny Lyon

In Mississippi, violence and the threat of violence were everywhere. In February 1963, Moses would survive an assassination attempt that badly wounded Jimmy Travis, a twenty-one-year-old SNCC worker from Jackson. In March, I drove south with another student, Bill Zimmerman, and we stayed overnight in SNCC’s office in Greenwood, Mississippi. It was firebombed the next day.

On June 9, 1963, six movement people were pulled off a bus in Winona, three of whom—Fannie Lou Hamer and June Johnson of SNCC and Annell Ponder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)—were taken into the back room of the police station, tied to a bench, and whipped by the police. They were returning from a workshop on voter registration. Three days later, in Jackson, the NAACP leader Medgar Evers was assassinated as he stepped out of his car in front of his home.

That same month, I finished school in Chicago and, at Forman’s urging, flew to Atlanta to become SNCC’s first—and, at that point, only—staff photographer. I was paid $35 a week and given a Southern Airlines credit card, the first and only credit card I would have for many years. SNCC had been formed eighteen months before my visit to Albany. Its first paid staff member was Jane Stembridge, a gay, white Southern woman. By the time I joined, it had sixty staff members, mostly Southern black former students, but also Northern blacks (Moses was a math teacher from New York City, and Forman was an air force veteran who had been president of the student body at Roosevelt University in Chicago), and a handful of whites, many of whom were Jewish.

Casey Hayden, a stunningly beautiful SNCC worker from Texas, later wrote that “we were the beloved community, harassed and happy, just like we’d died and gone to heaven and it was integrated there. We simply dropped race.” She was waiting for my bus when it reached Atlanta. “You can stay at my place,” she said. When we had met the summer before, John Lewis had been a staff member who had requested ten dollars to go to Cairo as a field worker. Now he was SNCC’s chairman. I got an apartment with John and Sam Shirah, a white boy who had led the Postman’s march through Alabama. That group of ten black and white SNCC and CORE workers ended up in the Alabama penitentiary. Sam’s ancestors had fought for the Confederacy, and he was from the same Alabama town where John’s had been enslaved and where John himself grew up. Dottie Zellner, who would befriend me in the Atlanta office, said it was the “cross-pollination” that made SNCC so effective. That a black and a white from Troy, Alabama, and a Jew from New York would live together was typical.

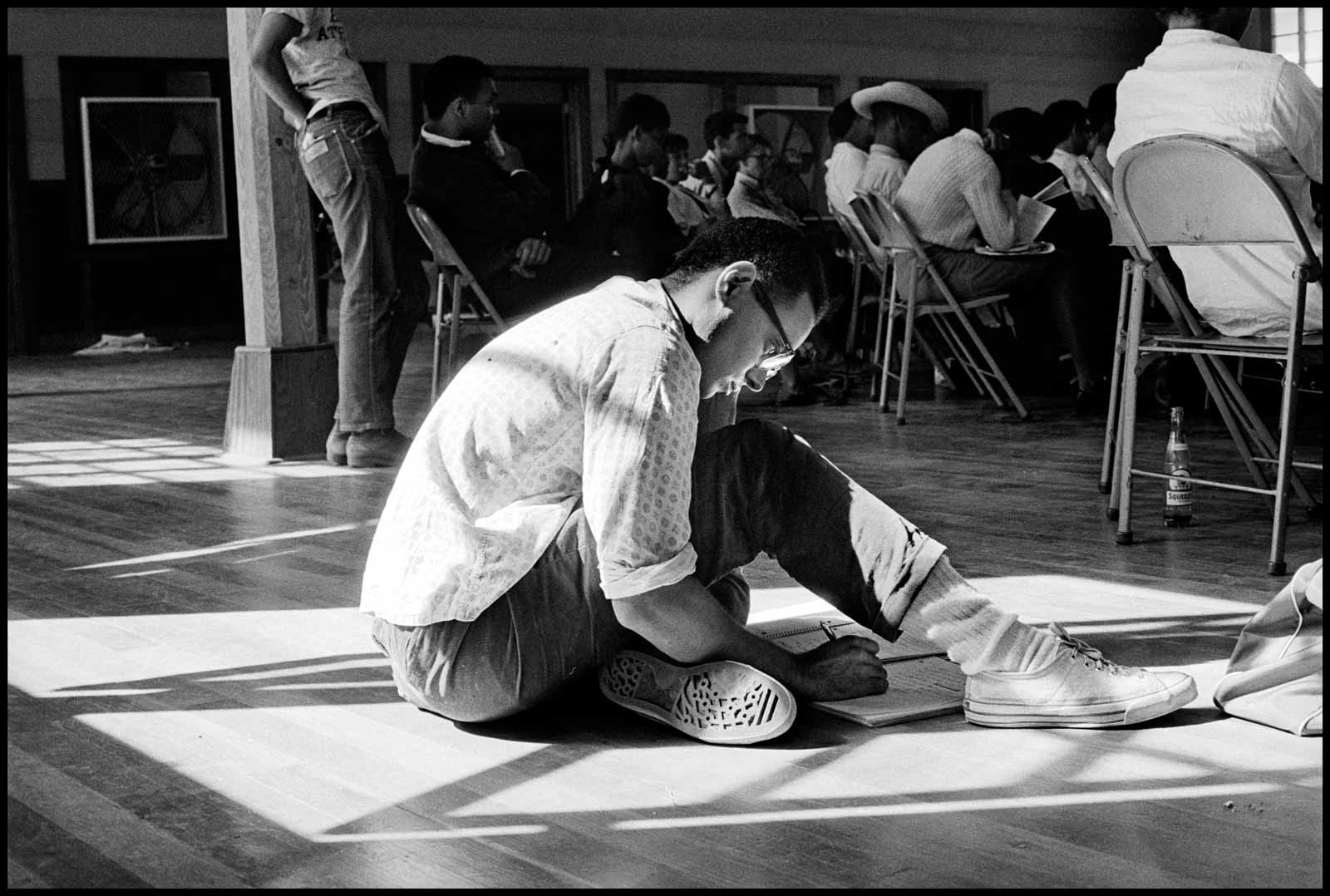

That summer, with my credit card and Forman’s leadership, I would visit every major SNCC project and be present at almost every major confrontation. The writer and civil rights historian Taylor Branch called it the “firestorm.” More than 14,000 people, mostly black and young, were arrested in protests across the South. It was the high water mark of the movement. At the Atlanta office, I set up a darkroom in a closet and shared an office with Dottie Zellner and Julian Bond, whom Forman had hired because Bond’s résumé said “journalism.” Together, we turned out posters, pamphlets, and flyers using my pictures.

Danny Lyon/The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

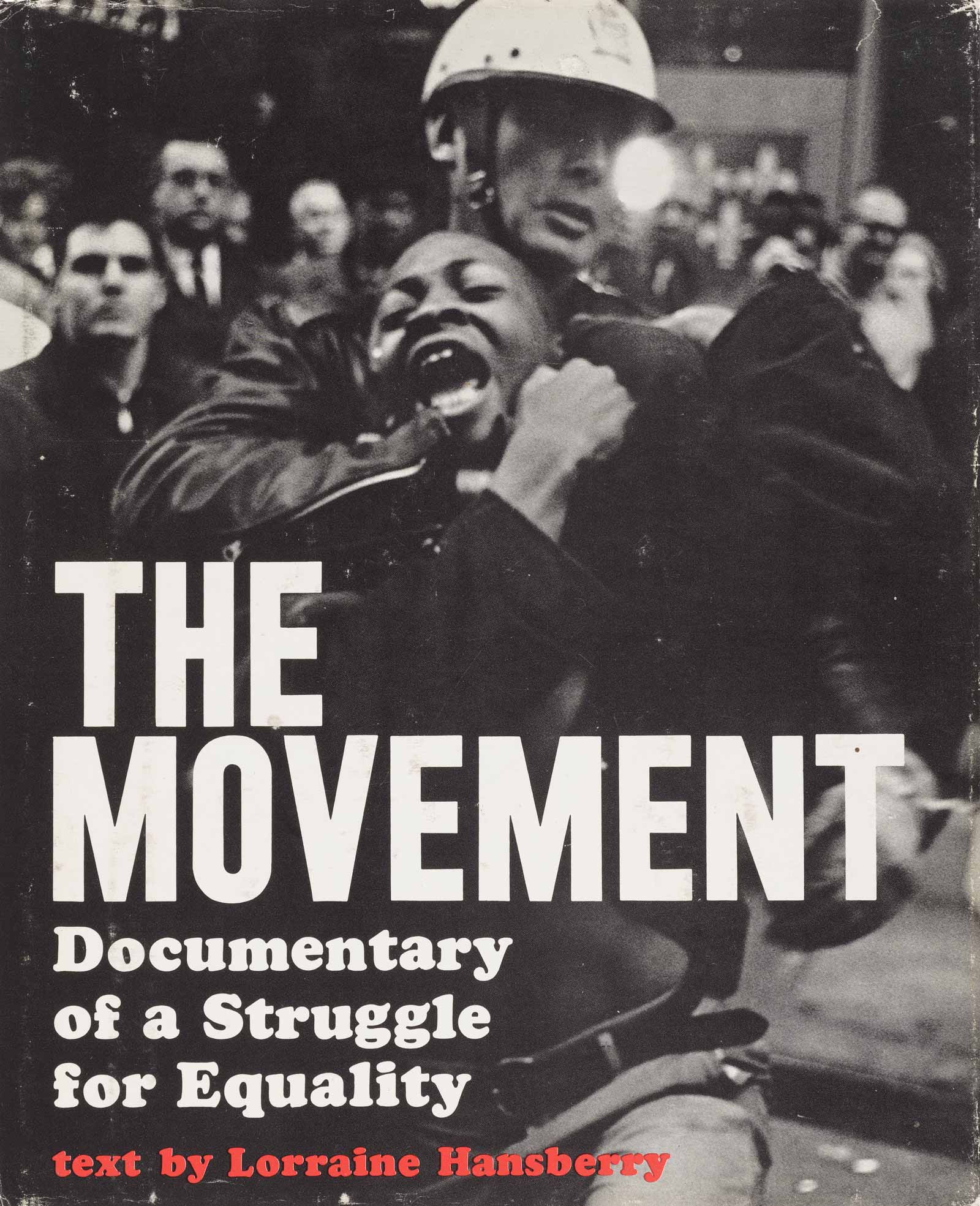

Cover of The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality, with photographs by Danny Lyon and a text by Lorraine Hansberry, Simon & Schuster, 1964

On my first day at the office, I saw a young black man struggling at a typewriter. Dottie Zellner pulled me aside and said: “Don’t help. It’s important he learns how to type.” She also said that “Mississippi belongs to Bob,” by which she meant that while Forman oversaw SNCC projects in Georgia Alabama, Maryland, and Arkansas, Moses did what he wanted in Mississippi. In a letter he wrote in 1961 from the county jail in Magnolia, Bob called it “the heart of the iceberg.”

Every six months, SNCC would have a “conference” at which powerful leaders would appear, including Ella Baker, the SCLC leader who had helped found SNCC. One was held in Washington, D.C., soon after the murder of John F. Kennedy. There was also a black nationalist meeting going on nearby, and after one session, a small group of SNCC people, including Courtland Cox, John Lewis, and me, went over to see what they had to say. On a long table at the entrance were pamphlets and literature. To my dismay, as we were about to enter, a person at the door nodded toward me and said, “He can’t come in.” I gestured to the table and the photographs on the covers, saying, “I took some of those,” and as I turned to leave John followed me out of the room. The other SNCC people walked in.

That winter in Atlanta, Sam Shirah and I went to a New Year’s party in an apartment—really, just a group of movement people sitting on the floor drinking cokes and beer and eating chips. Ruby Doris Smith, a veteran who had served a hundred days in prison with SNCC, was holding court, and at one point I distinctly heard her say, “I can’t believe we still have them on the staff.” I had been photographing the golden age of the movement, a time when it was nonviolent, integrated, idealistic, and successful. What I heard Ruby say sent a chill through me. It was the writing on the wall. My mother had also clipped a New York Times interview with Bayard Rustin, who had organized the March on Washington, in which he said that whites should work in the white community.

On the night before the 1963 March on Washington, I had slept on the floor of John Lewis’s hotel room. When I walked down to the lobby that morning, Malcolm X was standing there, a very tall, red-headed man surrounded by reporters. Fifty years later, I filmed John at a recreation of the march, and he showed me the star embedded on the steps where Dr. King had stood to make his “I have a dream” speech. In his speech about the march, Malcolm had said, “They told those Negroes what time to hit town, how to come, where to stop, what signs to carry, what song to sing, what speech they could make, and what speech they couldn’t make; and then told them to get out town by sundown”—which had some truth in it, as John’s speech was too radical for the coalition behind the march. Just hours before he gave it, he, Forman, and Courtland Cox censored it in a bathroom under the steps of the Memorial. I seem to have been the only photographer among the thousands there who took a picture of John as he spoke. To be honest, I didn’t bother to listen to King.

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Verso of the Mississippi Summer brochure, listing the SNCC staff of 1963

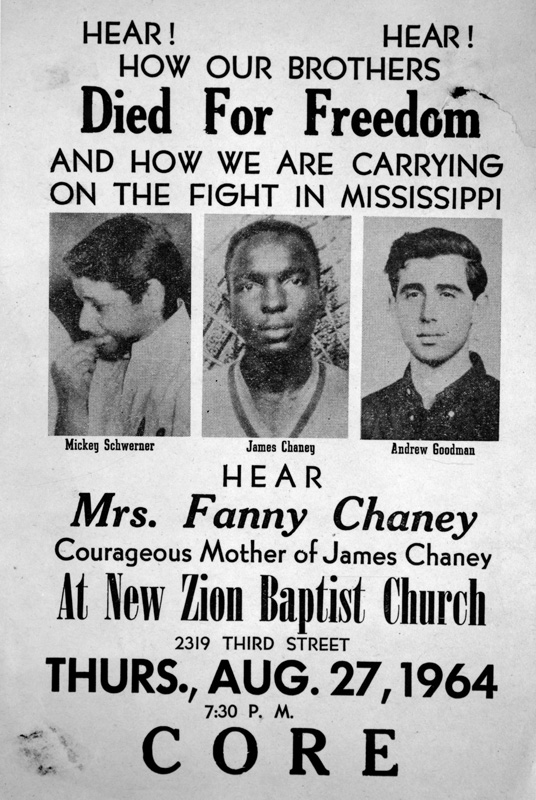

USA. Mississippi. 1964. A poster calls for a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) meeting. Pictured are slain civil rights workers Mickey Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman.

When the summer project of 1964 started, bringing a thousand mostly white Northern college students into Mississippi, I didn’t particularly want to go. For one thing, there were now many other people photographing the movement. For another, I thought voter registration was a bore. I found direct action, sit-ins, and marches, all of which often led to arrests, more exciting to photograph. Then, on June 21, a week before the project started, two workers and a summer volunteer were spotted changing a flat tire outside of Philadelphia, Mississippi, and taken to jail while the sheriff gathered the Klan to plan their murder. James Chaney was a black Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) worker from Meridian. He died, along with his best friend, a professional organizer with CORE from New York City named Mickey Schwerner, and Andy Goodman, a Queens College student and summer volunteer who had been in the South two days. A black Southerner and two Jewish boys from New York were lynched for trying to register African Americans to vote in a state that had lost the Civil War—but won back the power over their former slaves twenty years later by denying the right to vote through terror.

I had made the pamphlet that had been distributed throughout the North to bring volunteers to the South. So I got on a plane and returned to Mississippi, knowing it was no longer the grassroots movement I had witnessed two years earlier. That November, there was a SNCC conference in Waveland, Mississippi. By then, I had left SNCC and rented a place in Treme, in New Orleans. Sam Shirah and I got on my motorcycle to see if we could meet any girls in Waveland. I went through the conference room photographing the SNCC workers I knew, knowing I would probably never see them again.

In 1966, in a late-night meeting after many of the voters had left, Stokely Carmichael was elected to replace John Lewis as SNCC’s chairman. John was stunned, arguing that Carmichael wasn’t even from the South. “I’m from Alabama,” John would say, after the fact. “I don’t have to tell people I am black.” Later that year, speaking from a stage during a march with Dr. King, Carmichael first used the term “black power.” The crowd loved it.

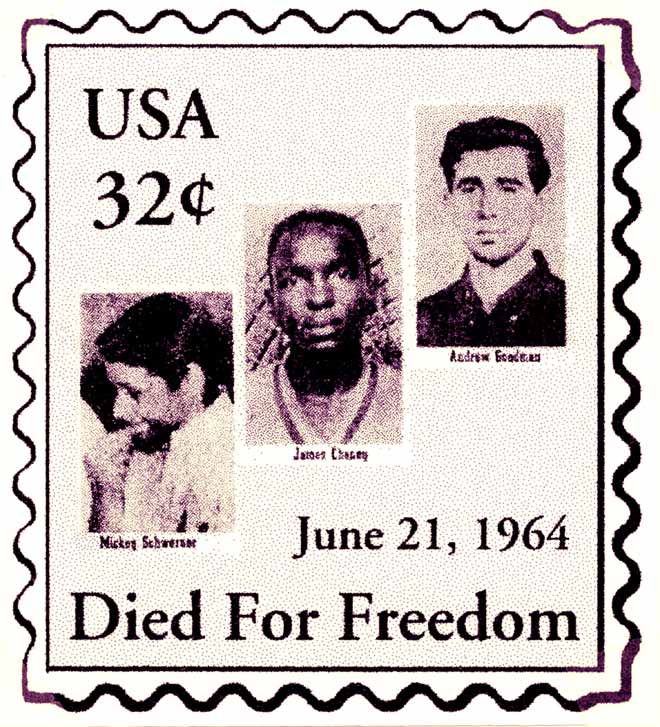

Stamp in memory of James Cheney, Micky Schwerner, and Andy Goodman, designed by Danny Lyon and his class at CUNY, 1990s

At a 1967 meeting, as Dottie and Bob Zellner sat outside, the remaining staff debated expelling the last two white staff members. Both had been in SNCC for five years. James Forman, who had been replaced by Ruby Doris Smith as executive secretary, came out of the meeting to tell the couple the news, saying later that it was the hardest thing he ever had to do. One of the boys I photographed at Waveland was Ralph Featherstone. By 1970, when SNCC was virtually non-existent, Featherstone, like many SNCC veterans, had become a Black Panther. A bomb later went off in his car and killed him.

Although I was a paid staff member, I always saw my work with SNCC as journalism. After 1964, I thought my part was to see what was happening in America, to see what the press didn’t see, and show it to the world. When John was knocked unconscious on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, I watched it on television. (By then, I was a member of the Chicago Outlaw Motorcycle Club.) In the march that followed, a Detroit housewife, Viola Liuzzo, was shot to death by the Klan as she ferried marchers to the Birmingham airport. A white woman was murdered for being in a car with African-American men.

As these events were unfolding, there was no question in my mind that protest against the war in Vietnam was eclipsing the Southern civil rights movement. The same newspapers that had been running stories about Sam and the marchers when they were jailed began to run more prominent articles about Vietnam. Many movement people became part of the growing antiwar movement—among them Diane Nash, John Lewis, Julian Bond, and Dr. King himself. My student friend Bill Zimmerman, who had become politicized on our early trip to Mississippi, would help create Medical Aid for Indochina (MAI), which raised money for medical supplies for North Vietnam.

On October 21, 1967, I was knocked unconscious on the steps of the Pentagon by a club-wielding military policeman. Hidden inside my clothes was my Nikon F reflex. Inside jail, I used it to photograph Norman Mailer, who would win the Pulitzer Prize for Armies of the Night, which gave an account of that day when 100,000 people marched and 700 were arrested. I was number four. When Dr. King was assassinated, my Nikons and I were inside the Texas prison system, where I was working on my book Conversations with the Dead. It was April 4, 1968. “Why now?” I thought. “The movement is dormant. No one cares about Dr. King anymore.” How wrong I was. That night furious African-American protesters burned downtown Cairo. It never recovered.

I was also wrong about never seeing any of my SNCC friends again. In 1989, I attended the Trinity College SNCC conference in Hartford, Connecticut. I walked in and there they all were. It was as if a fantasy world I had once lived in had come alive, and all my heroes and heroines were real people, sitting there in front of me. Mike Thelwell, a SNCC worker and former Black Panther, a poet, novelist, and teacher at Amherst, apologized for the expulsion of the whites from SNCC. Bob and Dottie Zellner were sitting there. “We had no cards to play,” said Mike. Dottie Zellner will be eighty years old this year. Bob Zellner is still an activist in North Carolina. Julian, Carmichael, Forman, and so many others are gone. Ruby Doris Smith died of cancer at the age of twenty-five. Sam Shirah was shot and killed long ago. They are, all of them, among the bravest and best of all Americans.

That day in Washington when John showed me the star where Dr. King had stood, I listened to Al Sharpton, the keynote speaker at the 2013 march, as his voice boomed out through the public address system.

“And when they ask us for our voter ID, take out a photo of Medgar Evers. Take out a photo of Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner. Take out a photo of Viola Liuzzo.

“They gave their lives so we could vote. Look at this photo. It gives you the ID of who we are.”

Danny Lyon’s Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement is available from Twin Palms Publishers. More information about his years as SNCC’s staff photographer, including his 2016 conversation with Congressman John Lewis at the Whitney Museum, can be found on his website, bleakbeauty.com. Words © New York Review of Books, where this article first appeared.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.