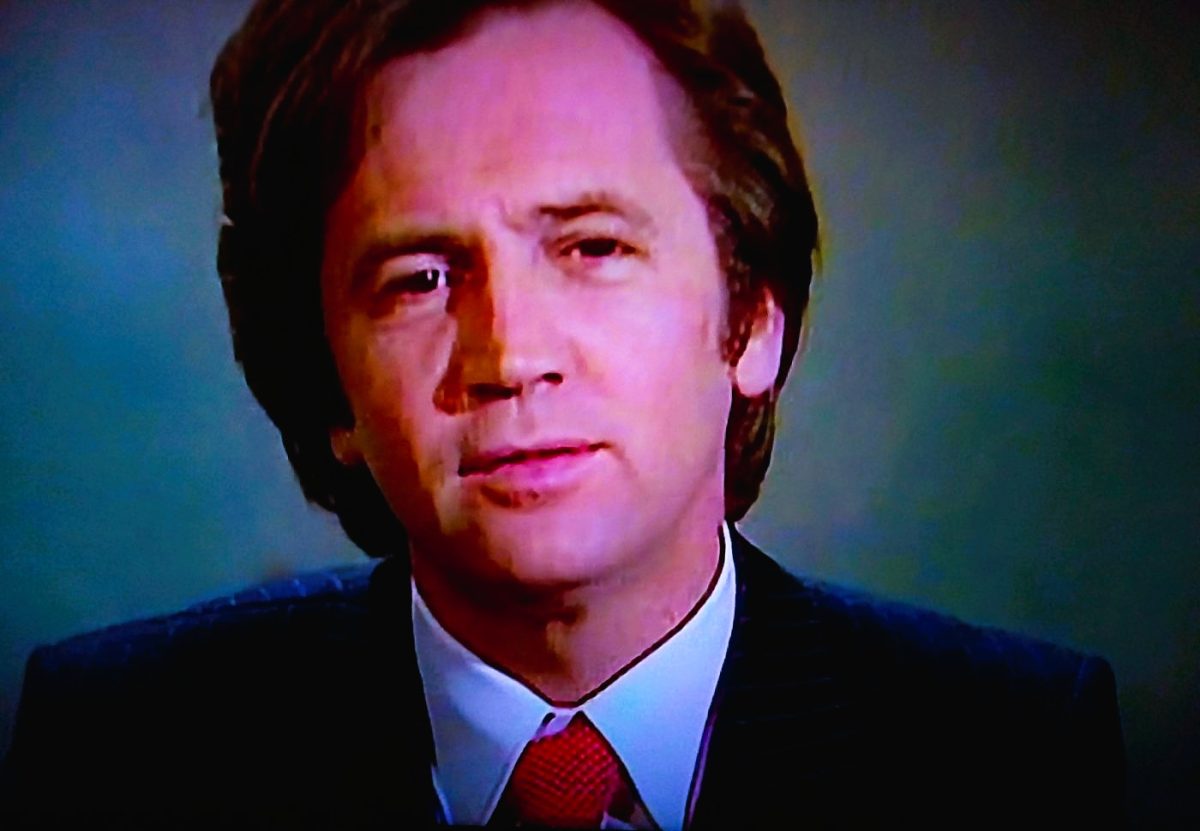

“I wear suits now basically because it’s easier if you are doing a television programme to wear the same thing all the time. You don’t want to go in way over the programme. It’s another way to get people to forget about me and concentrate on the person I am talking to.”

– Melvyn Bragg, 1984

May 15th 1984: You walk into the ground floor reception of the South Bank Studios, London. Outside, it’s a bright blue sky day. Wind whips around this black and white multi-storey building. Smell off the Thames. Glitter of traffic crossing over bridges. A young woman in her twenties greets you. She says your name then come this way. You go into a lift. Up sixteen floors to an open plan office. You try to make small talk. Out of the lift. Bright ceiling lights. Desks with young people busy working, talking, keyboards clicking. You wonder if you could ever get a job working here. You’re offered tea or coffee. Water, please. I’ll let him know you’ve arrived, she says. You are here to interview Melvyn Bragg. Through glass panels you can see into his office, hear him speaking. Then you’re led in.

Bragg sits behind a large executive desk. Papers, files, mail carefully displayed across the top. He stands up. You shake hands. The office is a wide rectangle with a view over the Thames, the Houses of Parliament, the OXO building, Saint Paul’s Cathedral. On the window ledge behind Bragg are a potted plant and a selection of books. Graham Greene, John Mortimer, M. M. Kaye, Roald Dahl. Bragg asks about your journey down. You have travelled from Glasgow on an overnight bus. But you don’t mention this. What are you studying? History. I studied History too. You set up a tape recorder. The assistant returns with a glass of water. You’re nervous. Should have written more questions. You worry your hand might twitch as you take a-hold of the glass. Sit down. You do.

Bragg is in his mid-forties. Wears a dark suit, silk handkerchief poking from breast pocket, white shirt, tie loosely knotted. You wonder why he always wears a suit. You wear black cargo pants, a grey denim jacket, John Lennon specs and high-top sneakers. He says: “I wear suits now basically because it’s easier if you are doing a television programme to wear the same thing all the time. You don’t want to go in way over the programme. It’s another way to get people to forget about me and concentrate on the person I am talking to.”

Melvyn Bragg: Doing The Arts

Since 1978, Bragg has edited and presented The South Bank Show. On one wall a white board lists the subjects of the current series in blue and red marker pen. Jack Lemmon, Catherine Cookson, Ed McBain, and Ken Russell’s Symphonic Portrait of Vaughan Williams. You have been a fan of the show since its first episode when Bragg interviewed Paul McCartney. Saturday 14th January 1978. Your father’s birthday. The South Bank Show was more of an arts magazine programme then. It evolved into single subject programmes. Bragg’s idea was to mix high art and popular culture.

Bragg tells you: “I think The South Bank Show is the most eclectic Arts show there’s ever been and it deals thoroughly with every subject that comes up. We make straightforward accessible programmes. It reaches out very democratically. We don’t talk down to anyone. I don’t think anyone respects you for that.”

You first got hip to Bragg when he presented a book review series on the BBC called Read All About It (1974-79). You watched the show with your parents and brother. You were working class but your parents had aspirations towards self-improvement. To learn. To read. Your father may not have read any of those red bound Russian novels from the Heron Book Club, but he wanted you to read them.

Bragg is a highly talented and original writer. At the time of this interview he has written twelve novels (including The Cumbrian Trilogy – The Hired Man, A Place of England, and Kingdom Come), and four books of non-fiction including a biography of Laurence Olivier.

His novels reflect his Cumbrian upbringing and his antecedents – farm labourers and coal miners – which has lead to a few critics describing his work Lawrencian. He has also written about people who work in television. His books are brilliant examinations of working class life in the 1800s to life in the more complex and cosmopolitan world of the 1970s.

You have read six of his novels. The most recent read The Nerve caught your imagination . The story of a man having a nervous breakdown. You wonder if Bragg has had a breakdown. You don’t know. And you are unaware until much later that Bragg’s first wife committed suicide. People only tell you what they want you to hear. You wonder again if you have enough questions, if you know enough about your subject.

Fuck it.

Interviews are not just about questions, they are about listening. Listening to an answer then interrogating it. It’s a conversation. It’s about engaging with the interviewee and the subject matter.

Another reason you like Bragg is because he worked with Ken Russell. You want to know more about this. But this will come later.

You ask your first question: How would you describe yourself? Bragg is eating an apple. Lunch. He pauses and thinks before answering.

“I’m a writer and a broadcaster. I’ve done the same thing since I was about twenty-one or twenty-two. I started out writing short stories and knew that’s what I wanted to do. I also knew that I wouldn’t be able to make a living out of it so I had to get a job. I got a job making television programmes. I liked doing that a lot. I liked everything about it. I like working with other people for a start. I don’t like the life of a writer in terms of being on your own all the time writing and reading. I don’t like that. I like that to be a part of my life but I don’t like it to be all my life. I get too depressed. I get too cut off. I like working for other people. So I do two things. It’s what I’ve done all my working life and I don’t see any division in it.”

Bragg’s words “depressed” and “division” catch.. But you are nervous. Instead you ask what you’ve already written down.

You are a writer, a broadcaster, a journalist and a screenwriter, do you think you may be doing too much, spreading yourself thin?

Melvyn Bragg: Well, it depends how you look at your life. (Pause) One or two people say that. It’s a fairly modern phenomenon that writers have just written and I’m not sure they’re the better for it. I mean Dickens edited a daily newspaper at one stage apart from running campaigns and so on. Henry Fielding was until the end of his life a very busy magistrate. They’re very good writers. Ted Hughes farmed properly for years and years as well as writing poetry and verse and goodness knows what else. Philip Larkin has been a full-time librarian. Graham Greene wrote reviews until he was in his forties, about my age. So I think there is an idea around that writers should sit down and that’s fine for certain temperaments.

I would like to have spent more time writing than I have been able to in the last five or six years. As to whether my writing has suffered because I haven’t enough time to it – I don’t know. There’s always a balance, I think. Or there is a balance in my life. Of going and finding out about the world. being in the world and having to think about it and to work on it. Then going away from it. To sit down and write it. Especially novels because they tend to take a long time to write.

(You say nothing.)

MB: I would like more predictable, more solid time away from everything to start a book because you need about six weeks to start something. You need six weeks to get into it. It’s very hard to get but it’s much harder to get because of the family, because of the job.

But the family would be around if the job wasn’t around. Do you see what I mean?

I sometimes think that I’ve enough time to write. Instead of publishing nine novels I could have published two or three and taken just as much time to do it. I don’t think you, anyone has to moan about that.

I think it’s very, very difficult to prove on my part or anybody else’s that the books have been affected by the other work either for the better or the worse. I think the argument is unprovable.

Actually, I think it’s unimportant. If the books are good then they’ll hang around for a bit. Or, if they’re not, then they don’t deserve to. I actually take it as axiomatic which I think is perhaps a mistake. But nevertheless, I take it as axiomatic that if something is good it will survive. I think that is an axiom. An act of faith on my part. I don’t think there is anything else you can say that matters very much. If a book is good it will live on. If it’s not, it won’t.

How do you write?

MB: It depends. It’s very erratic from book to book. Silken Net took a year-and-a-half. Hired Man about thirteen days. Love and Glory sort of peddled along for about nine months quite steadily. I just kept slamming away at that. It depends.

I do first drafts. I write in longhand. I do an awful lot of writing and overwriting. I wish I did more.

I work on a book and when I see it out I think, ‘Oh, Christ, I could have done with another shot at it.’

Some critics have suggested your books are autobiographical. Is this true?

MB: I’ve used a lot of detail from life in terms of context and in terms of a general passage of a career sometimes. That is to say, I too was at a grammar school in a small mining village. I too went to Oxford and I too went into a broadcasting system and made television programmes.

In The Hired Man my grandfather was a coal miner and an old farm labourer. In that sense some characters have similar biographical details but there’s not much more to it than that.

When I have written sometimes about somebody who seems to be a bit like I can appear to be, it’s difficult for some to separate my life from certain lives in the books. But then when you look at the books, I mean the few autobiographical things that are in Want of a Nail are trivial, they really are. I can give you the six little facts there were and that’s a paragraph’s worth.

Second Inheritance was nothing to do with me at all. Without a City Wall nothing to do with me. The Hired Man is two generations ago. A Place in England is one generation ago. Same with Silken Net and Josh Lawton.

MB: When it comes down to The Nerve which I deliberately wrote using an autobiographical mode I knew I was taking a risk. I like taking risks. The thing is about being well-known and because of television diminished in the eyes of literary critics, I can take a lot more chances. I can take as many chances as I want. Because, fuck it. The snidies are always going to be out there and there’s nothing I can do to crack that lot. That’s all there is to it.

I can do whatever the hell I want. They can go and fuck themselves. They’re going to do that anyway. You can shit on any book in the world and London is full of extremely clever young men who can do that by the yard.

(You wonder if Bragg is including you in this swipe.)

MB: One of the things I wanted to do was run fiction very closely alongside documentary. To chronicle as to create. Especially to chronicle. I always liked that aspect of novel writing. I always did. A good shank of the novel was to be a chronicle of the times as well as to be an imaginative rendering of the times.

The first volume [of The Cumbrian Trilogy] The Hired Man is generally an accurate description of life – the hiring, the coal miner. I’m sure it isn’t faultless but it is generally accurate.

The second, A Place in England has a documentary accuracy of working class life in a small town during the interwar period.

Now, how was I going to carry the story on in the third [volume Kingdom Come] and stay with the documentation? I wanted to achieve three things. I wanted it to document a life. I wanted it to relate to my own family. I wanted it to be a work of fiction. The third volume meant I had to come into London. I had to come into television and all that. I delayed writing it for years. But I couldn’t get away from it no matter what I wrote. and I couldn’t get the central character balanced in my head. I couldn’t make him, couldn’t feel him at all. Then I just started to write and thought ‘Here we go.’ And that was the risk one took.

Do you think your work is taken seriously by the critics?

MB: They don’t take too many people seriously except for each other. Who takes who seriously? I mean Clive James gets shat on. Craig Raine’s last book didn’t get too well received. There are cliques in and out and in and out. I’m not at all paranoid about it, believe me. I do get some extremely good reviews. The last one [Love and Glory] got good reviews from good people like Fay Weldon, people I respect. What can be more satisfying than that?

I think [with critics] there’s a general five percent of smart, snidery that goes on. It isn’t at all important. You know what I mean? They pick up things like ‘Oh, he says that [character] Douglas [Tallentire] is such and such a chap.’ ‘Oh, that’s him, of course.’

You’re slightly aware of that so you’ve got to get unaware of that in order to make the book work. Actually, it’s a problem of comedy rather than anything else. If I had more confidence and a better talent then I would turn it into a comedy of juxtaposition because it is a trivial matter.

I’ve never had as much confidence as I’d like to have. I’ve always been rather in awe. That’s why I’ve enjoyed the television work a lot more.

Tell me about your childhood and how you started in television?

MB: When I was a kid I used to read novels. I read a hell of a lot of novels. I was middle-aged when I was younger. Very.

I got a BBC traineeship when I was twenty-one. Went into radio, which I liked an awful lot. Worked in Newcastle. Worked in the World Service, Bush House. Then I worked in Broadcasting House in the features department. I was going to stay there, I didn’t like television except for an Arts programme called Monitor. I said I’d only go into television if I could get an attachment onto Monitor. Eventually one came up and I got it and I went to Monitor. If I had been doing anything else I’d rather have stayed in radio.

On ‘Monitor’ you worked on a series of drama-documentaries directed by Ken Russell which led to working together on the movie ‘The Music Lovers’ which starred Glenda Jackson and Richard Chamberlain. What happened?

MB: I had a big row with Ken [Russell] on that which is fairly public. I hated [The Music Lovers]. Hated it. I thought the first screenplay I did was rather good.

[Pause]

I hated it. It all went wrong.

I think the first third or half stands up a bit. Then it just went to pieces.

I think Ken is a very brilliant, eccentric and erratic talent. He can be marvellous but the trouble was for a long time, in my opinion, Ken just lost interest in writers and that’s fair enough but the consequences just showed on the screen. He just was not interested in the writer’s contribution. He was interested in the director’s contribution. He was interested in the cameraman’s contribution. The actors’ and actresses’ contribution. But he was not interested in the writer’s contribution. And that’s a mistake that showed.

What it meant was that although you can have dialogue, you can’t have character. Writers can create character. Anybody can write dialogue. Anybody in the world with an education can write dialogue – he said that, she said that – anyone. I can write four pages of dialogue with my left hand while I’m talking. It’s just meaningless unless they are attached to characters who’ve come from somewhere and are going somewhere.

That’s what Ken got in the habit of thinking – what went on between two people was dialogue and not character. And that’s a shame. With The Music Lovers it was very depressing really and I gave up writing for films.

I’d had a good and a bad time writing for films and in the end I gave up writing films.

You know, life’s very short and the whole thing is an odd business anyway. You might as well do something that gets somewhere. I mean these television programmes on the Arts get made and they get shown. They matter to some people a great deal. The books that I write get written and get published and some people like them a lot. So I’d rather do that than write for films.

I mean if you want to make money and be glamorous then films are fun but I’ve never been particularly interested in it.

You also scripted films like ‘Play Dirty’ with Michael Caine and Karl Reisz’s ‘Isadora’ with Vanessa Redgrave.

MB: Now I enjoyed [Isadora]. That wasn’t anybody’s fault. Well, that was an amusing story.

The long version I’m proud of but nobody’s seen it in this country except at the NFT. I really was proud of it. But, that sickened me too.

The short story of it is that, I’m not telling you anything that isn’t true, but being abbreviated may be distorted.

Isadora which ran about 180 minutes and I’d structured it around Isadora’s memoirs. It took me bloody months to work out the structure. In the end the only way to do it was to have her as a blousy old lady dictating her memoirs on the Riviera. Now that seems very trite but when we did it in the sixties it hadn’t been done much. The problem you’ve got with biopics is that there is no structured drama in anybody’s life. What you’ve got are bits all over the fucking shop. And you’ve got to have that bit because she’s terrific. And you’ve got to have that bit because there’s hardly any relationship between them. Where if you write a play or a book there is a relationship because you have written it like that. But in people’s lives something happens there and seven years later something else happens.

Now the day before Isadora was going to have its trade showing Vanessa Redgrave burnt the flag of the United States of America on the steps of the American Embassy. It was wired all across America. It was a shocking thing for anyone to do. The next day this film opened with Vanessa playing a communist. Jesus Christ, they murdered it. ‘Do you want to see a Red actress playing a Red actress?’

The distributors panicked. They said it had to be cut so it could be shown five times a day instead of three times a day to make up for any losses. They took out fifty-odd minutes in a fortnight. I mean they just butchered all that marvellous storytelling stuff.

How did you become involved in making ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’?

MB: Skint. Utterly skint. I’d been out of a job for six years. I’d left television to concentrate on writing novels. Incredibly broke. We had a tiny house. It was over-mortgaged and borrowed on again. We were pressed to get rid of it. We were in terrible trouble. At the time it didn’t worry me a lot. It should have worried me a lot more. It worried other people like bank managers and solicitors.

I’d said to my agent I didn’t want any more films because I hated working on films. He rang up and said, ‘They’re stuck with Superstar and they can’t get it to work. If I send you a script of what they’re doing can you give me an opinion of it. and there’s five hundred quid in it for you.’ So, I thought it’s King of Kings with a beat. That’s what’s wrong with it. I hadn’t seen the show but I’d heard the record. It’s a contemporary pastiche. It works well as a pastiche. It now feels hackneyed but at the time it had a certain great freshness. So, I wrote that and they said, ‘What do you suggest?’ I got a ten week contract to work on it. I got paid weekly to pay off my debts and get the bank off my back.

MB: After about three weeks I’d cracked it. They’re going to make this film because I’ve seen how to make it. I did this terrific treatment. I said all you need in an amphitheatre is forty people. They didn’t believe it would work. They were worried about Blasphemy Acts, you’ve got to remember all that.

I said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do, if you give me a small crew and I’ll go to Israel and shoot parts of it with half-a-dozen actors I’ll pick up in Tel Aviv and I’ll plan the track, sequence it and show it to you on film.’

And I did. I made a terrific job of it. Actually, I think some of it’s better than the film and Norman [Jewison, the director] not only used a lot of my locations but also a lot of the camera positions I used in the shoot.

It was a wonderful time. A terrific time. It was sort of like playing. Going into an actor’s studio in Tel Aviv and asking half-a-dozen young people if they want to jump into a truck and go into the desert and shoot for a week. We all stayed in crappy hotels and there was no money in it. They’d very grudgingly given us stock, old cameras and we had playback on a tape recorder [Laughs] Great.

Are you religious?

MB: No. Not at all. I don’t believe in any of the things you believe in if you’re religious. I mean God, eternal life, resurrection and all that.

How would you like to be remembered?

MB: I couldn’t give a damn. It’s nothing to do with me. I hope the people who knew me thought I was okay. That’ll do.

****

With thanks to Melvyn Bragg.

Photographs by Michael Gallagher, used by kind permission.

H/T Planet Paul

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.