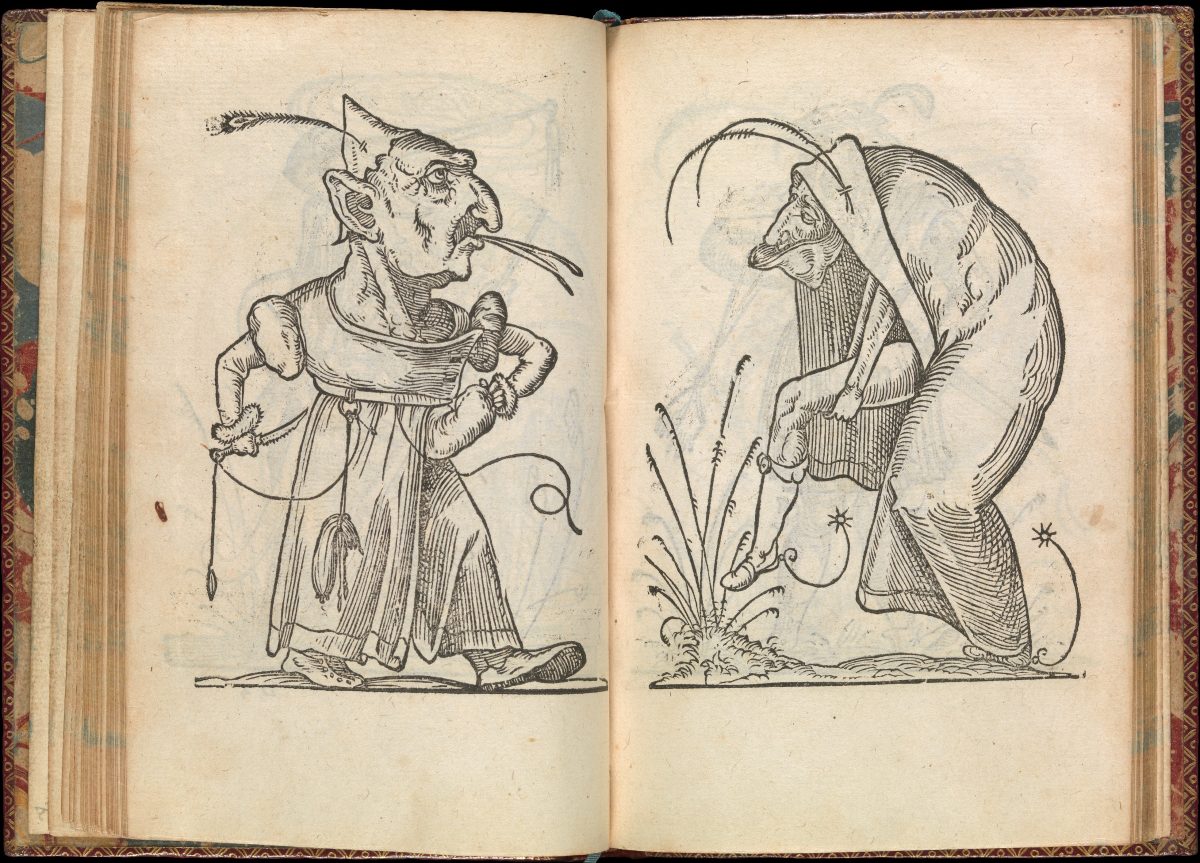

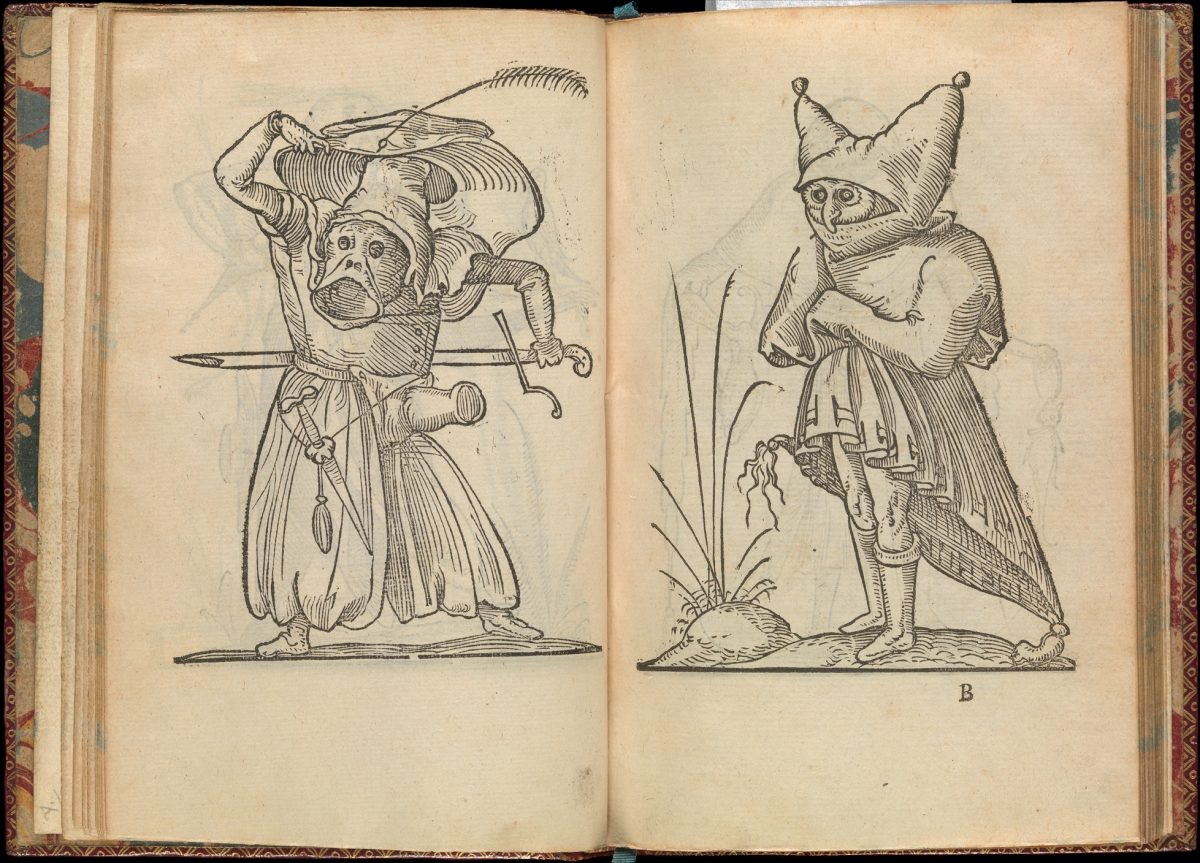

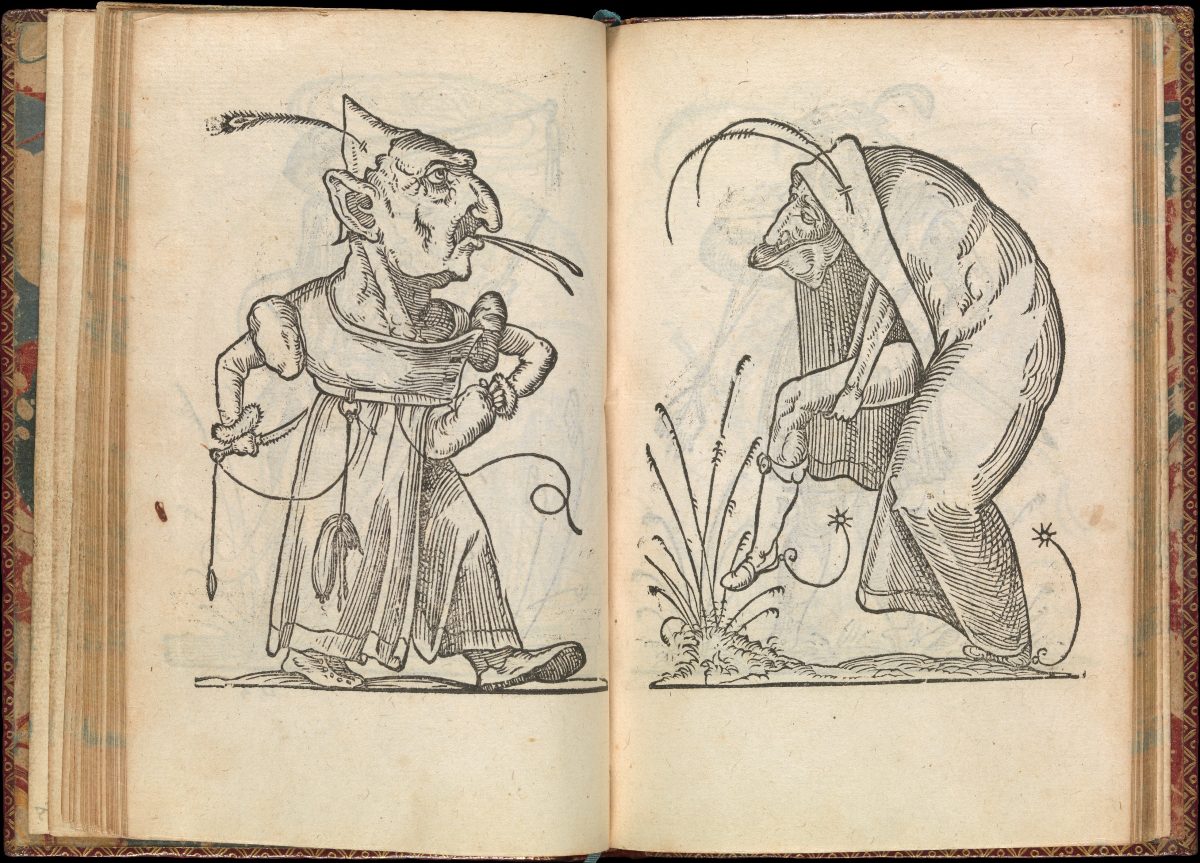

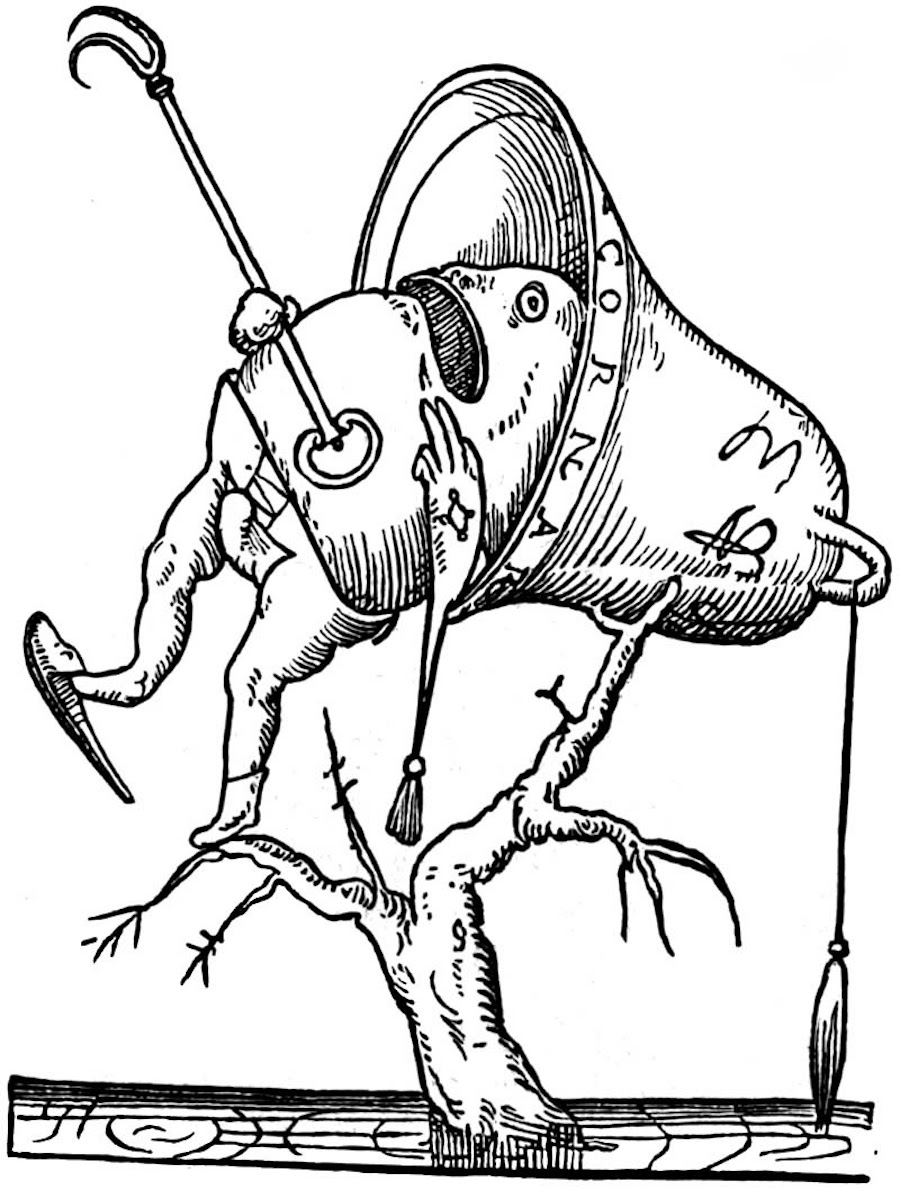

“The great familiarity I had with the late François Rabelais (dear Reader), has moved and even compelled me to bring to light the last of his work, the drolatic dreams of the very excellent and wonderful Patagruel, a man very famous for his heroic deeds on which the more than veritable histories write awesome things.”

– Publisher Richard Breton writing in the preface to Les songes drolatiques de Pantagruel (The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel), 1565

Breton is but our humble servant, pulling back the curtain to reveal things to amaze and hold you spellbound. As for the rest of the book’s title, Rio Wang has more:

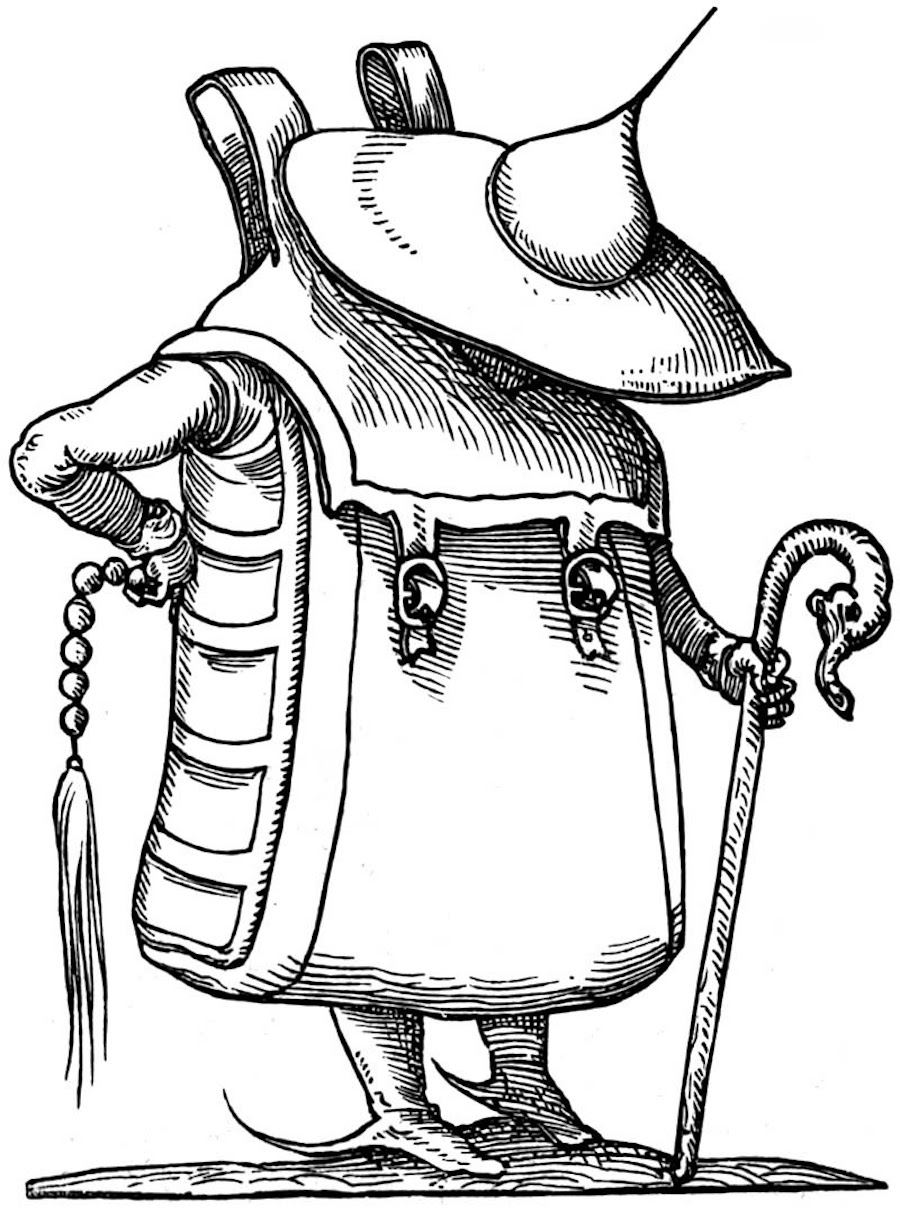

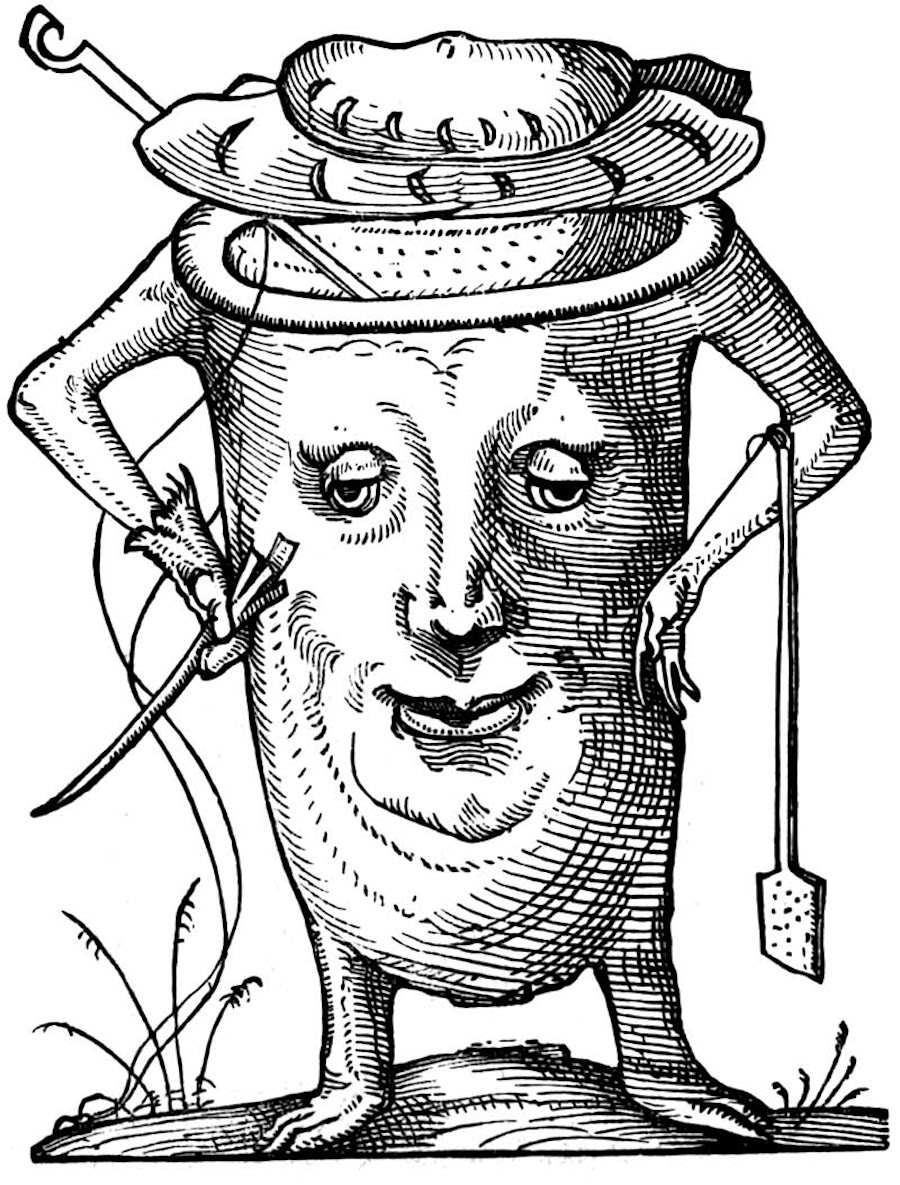

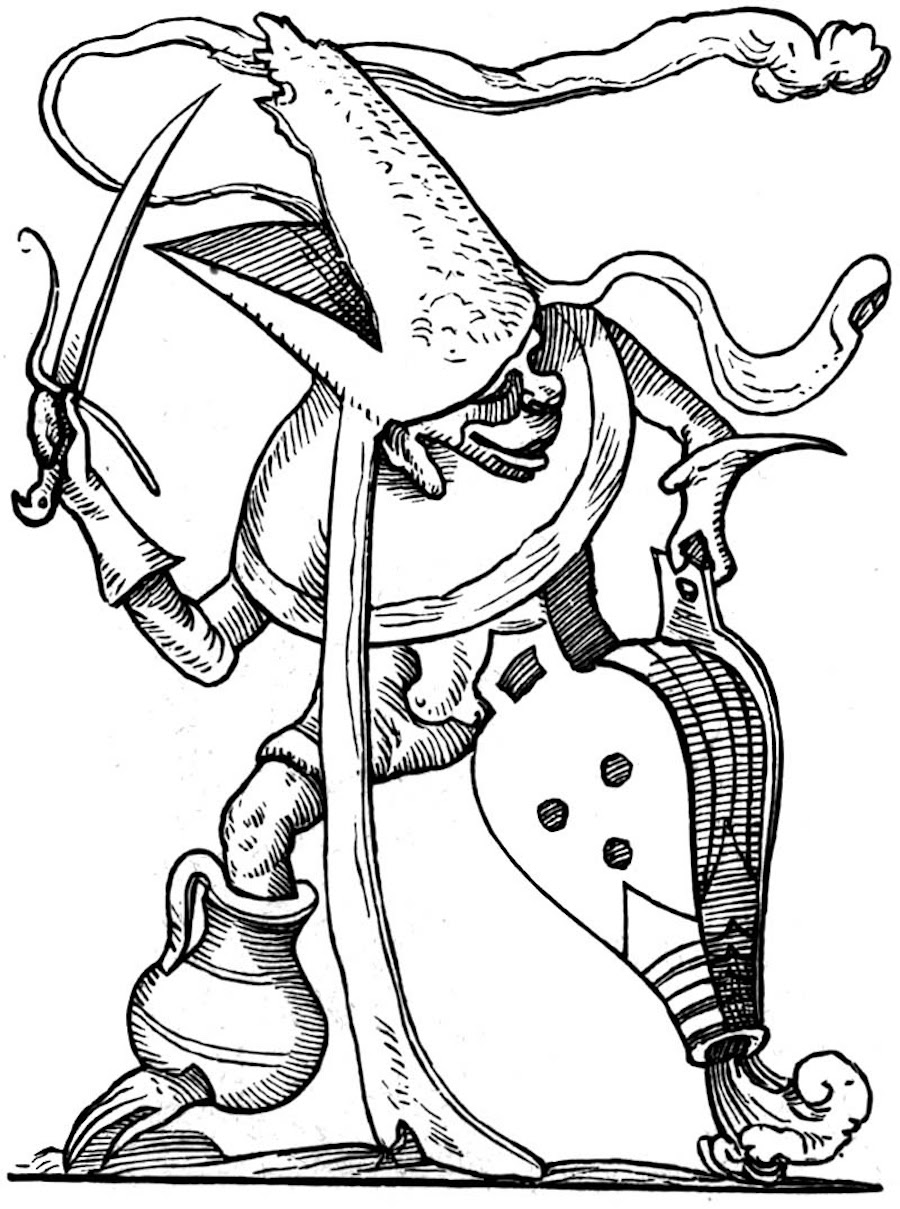

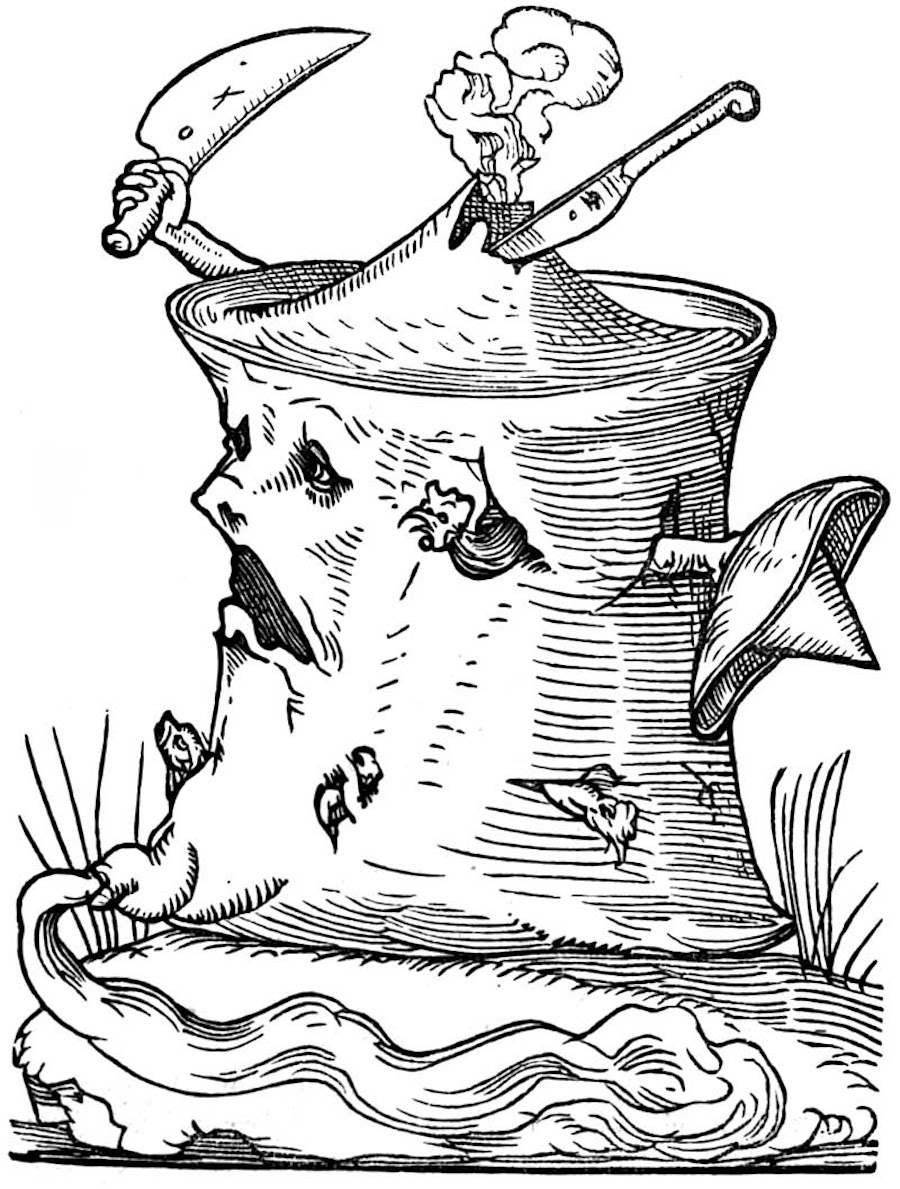

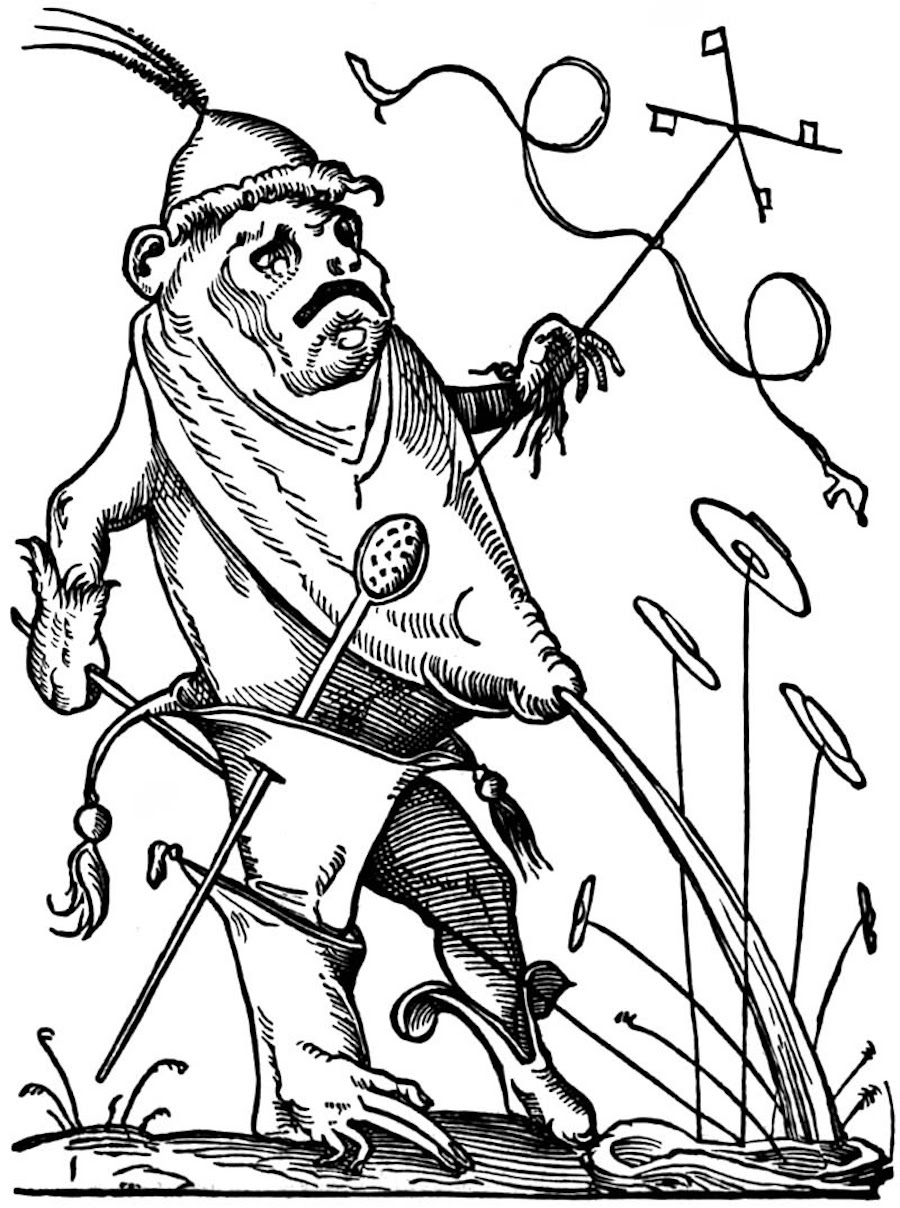

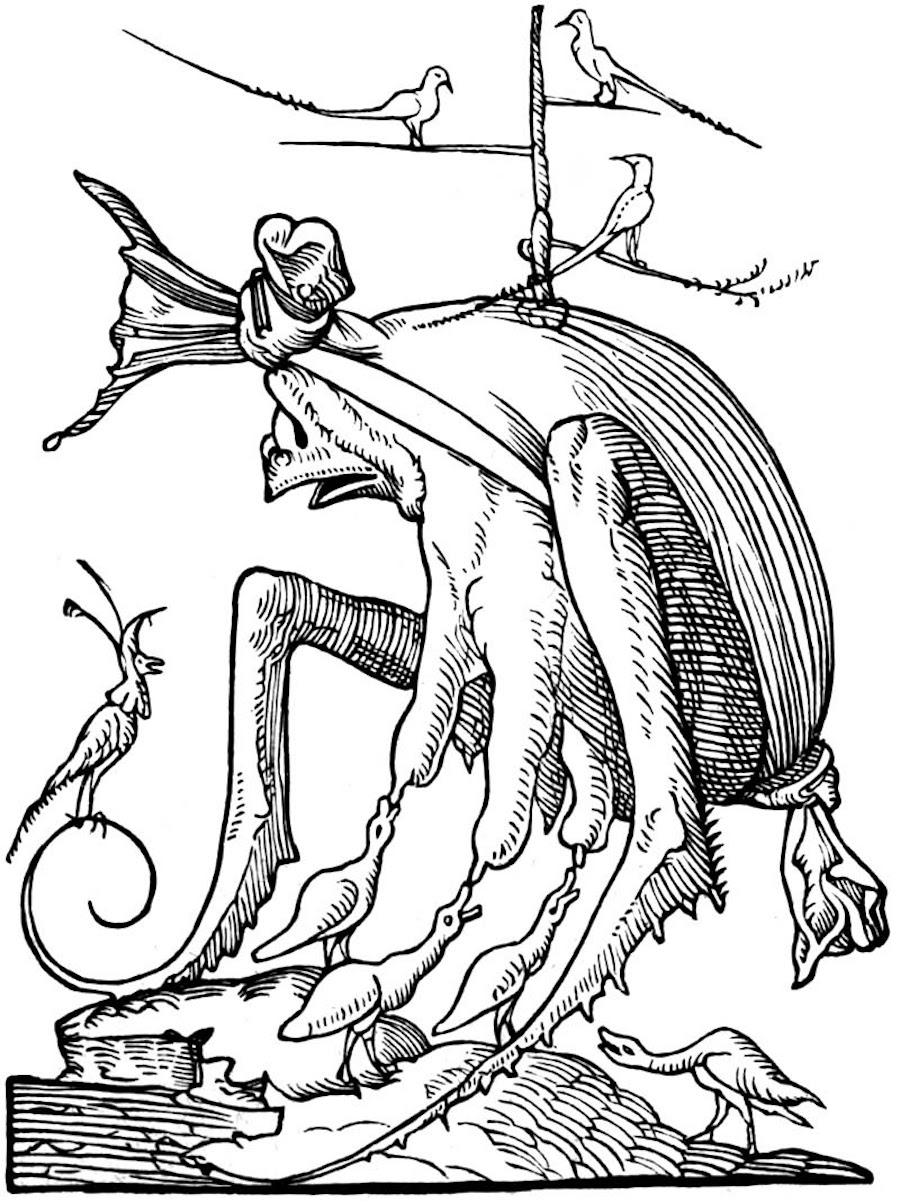

The title of the book includes an adjective (drolatique) which seems to appear here for the first time in French. Drôle means “funny, curious”, and this is the origin of the term drôlerie used by modern art history for the ornamental fantasies on the borders of medieval manuscripts or architectural decorations. Drôlerie is thus related to grottesco, but they are distinguished by the classical origins of the latter as contrasted to the medieval roots of the former. In late 16th-century France the meaning of drôlerie also included those satirical – and often grotesque – figures which since the beginning of the wars of religion flooded the press, as well as the animal-shaped masks and costumes… Some centuries later, in 1830 it was Balzac to use again this term when he chose the title Les contes drolatiques for a series of unlikely medieval stories which gave him occasion to an uninhibited, at times rough, or even obscene narrative, and whose fifth edition in 1855, five years after Balzac’s death, was decorated with 425 fantastic illustrations and vignettes by Gustave Doré.

“Drolatic” is an adjective of “dream” in the title, and we must ask what kind of dream is this. It is certainly the dream of reason, as it gives birth to monsters. And also a dream of revelation through which we acquire a knowledge impossible in wakefulness. That dreams (especially by virtue of the vis imaginativa during the conception and pregnancy) can literally give birth to monsters, was well known by contemporary authors of treatises.

You can see the 1565 original of Les songes drolatiques de Pantagruel – The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel – illustrations by François Desprez at BnF’s Gallica.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.