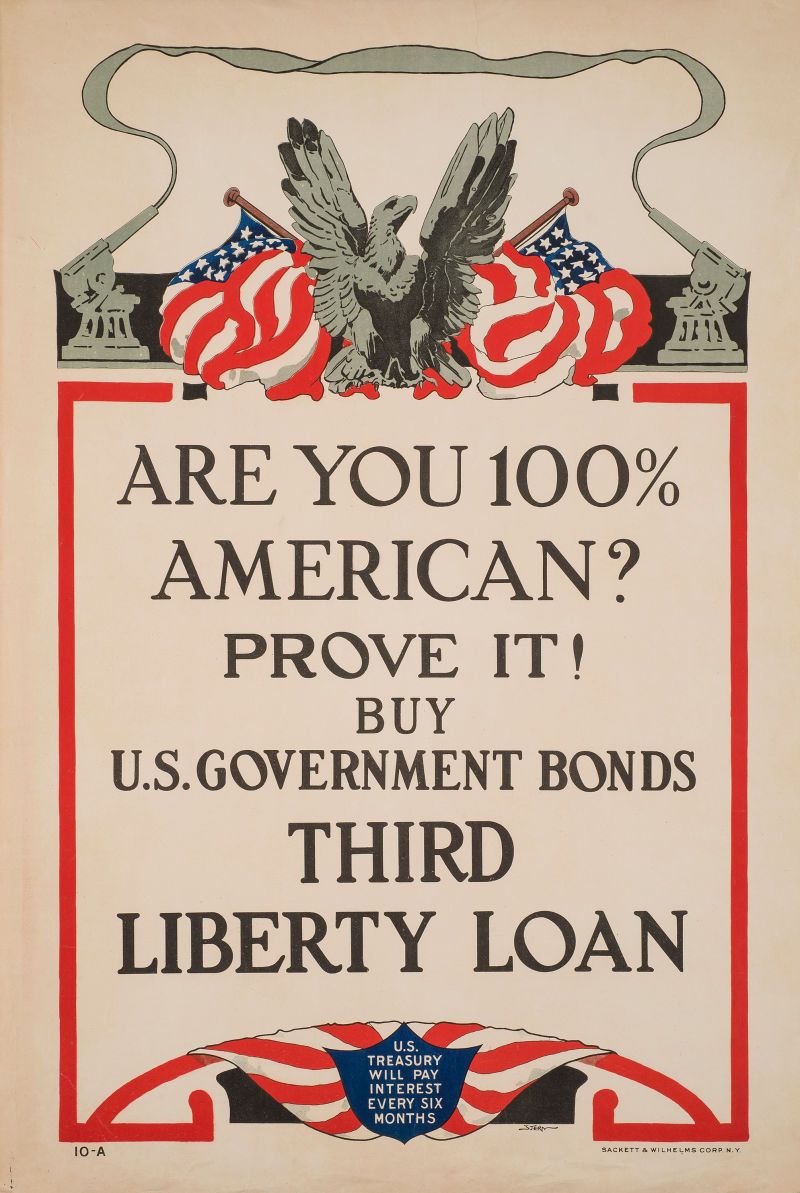

The civilian population of the U.S. was less than enthusiastic about the country’s entry into World War I. The “vehemently isolationist nation needed enticement,” writes Smithsonian, and it largely came in the form of posters “so well designed and illustrated that people collected and displayed them in fine art galleries.” In addition to the massive scale of weapons manufacture and industrial production, a huge propaganda effort urged young men to enlist, and convinced those at home to tend the food supply, get active in volunteer service, and—most importantly—buy war bonds.

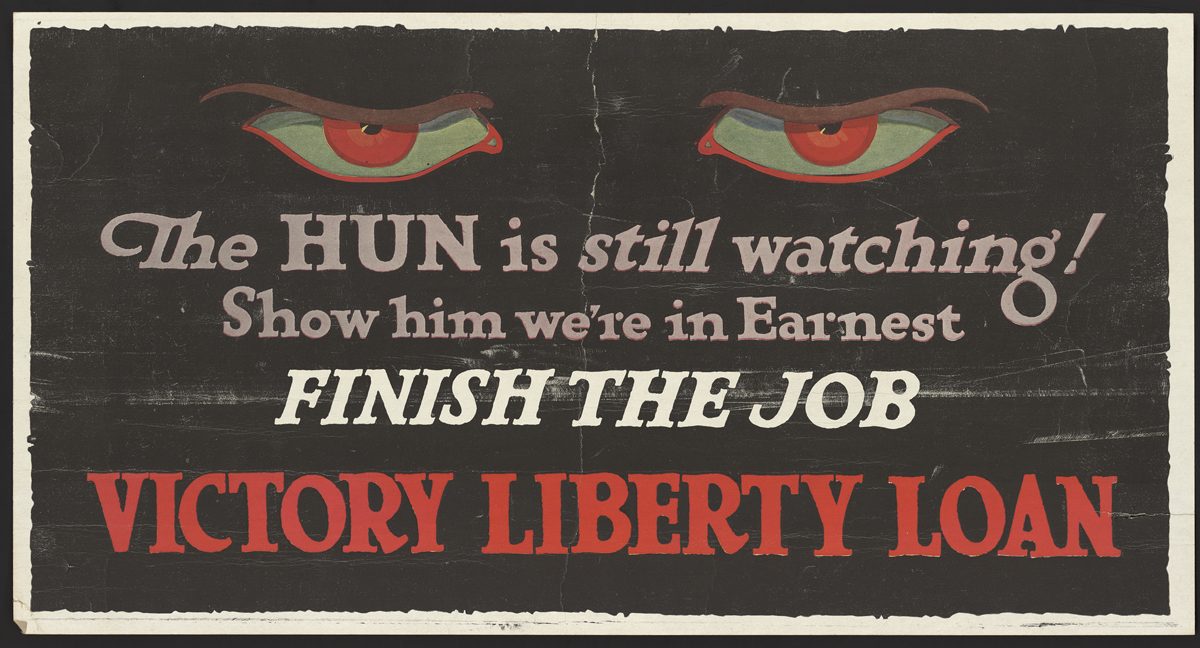

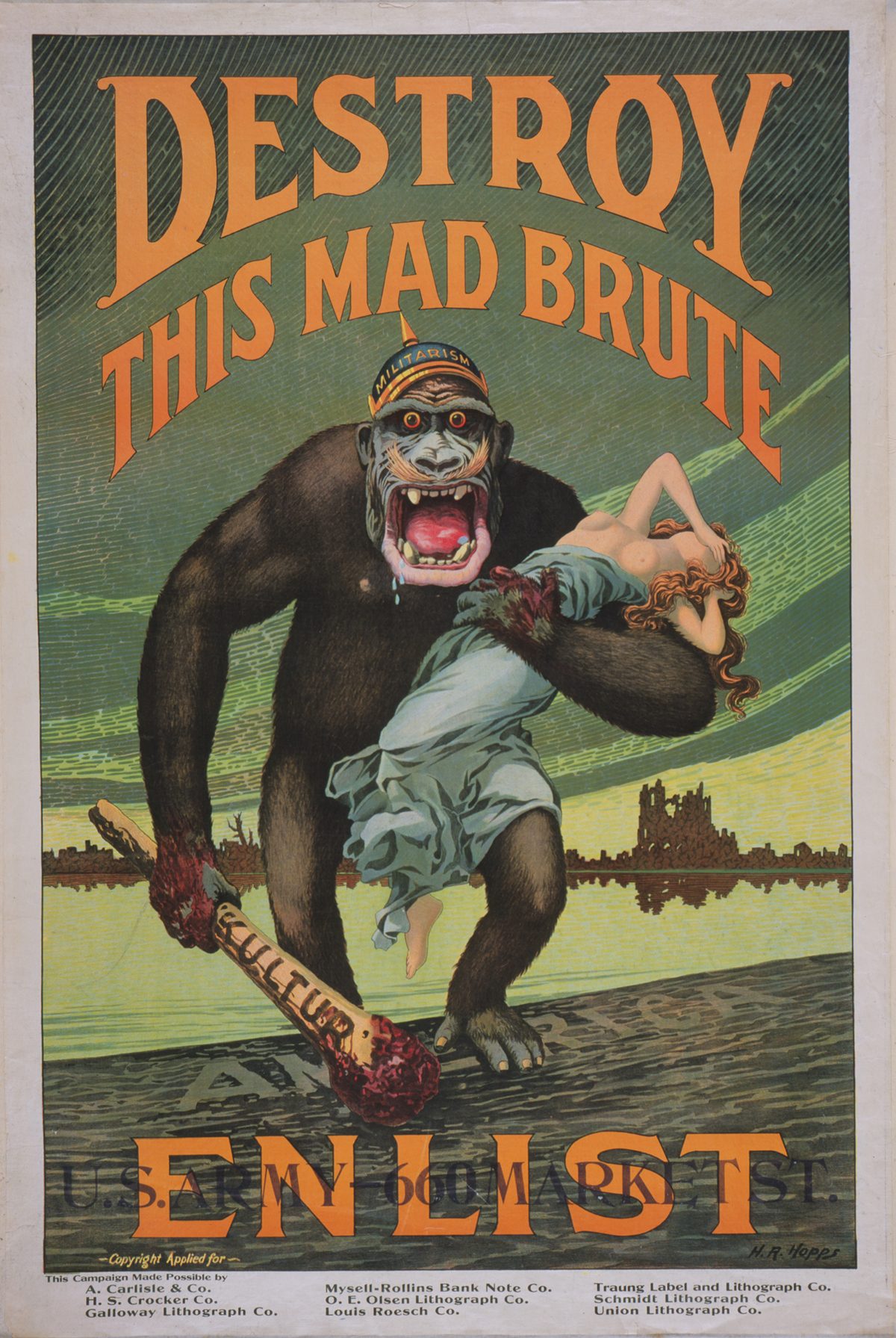

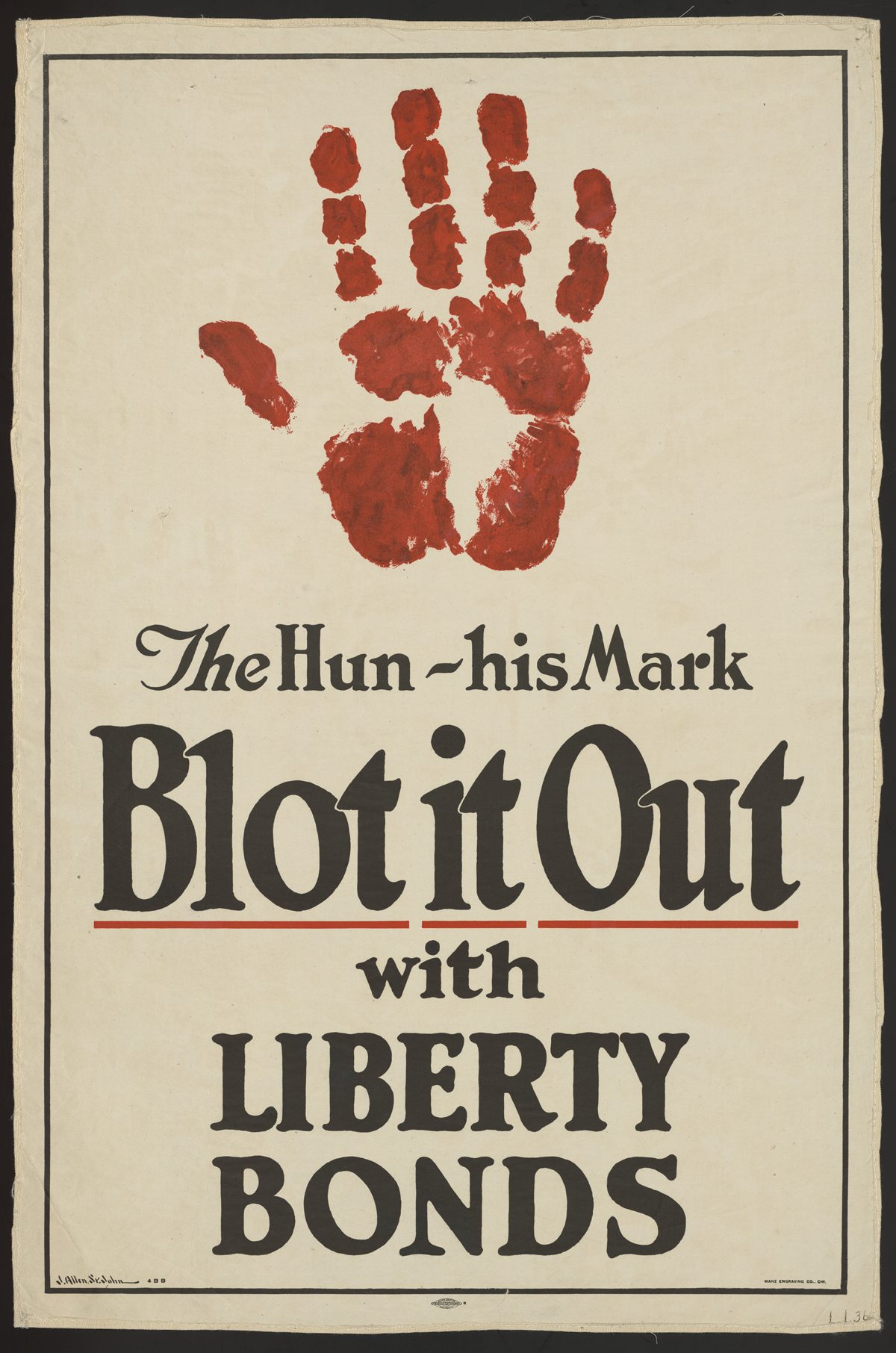

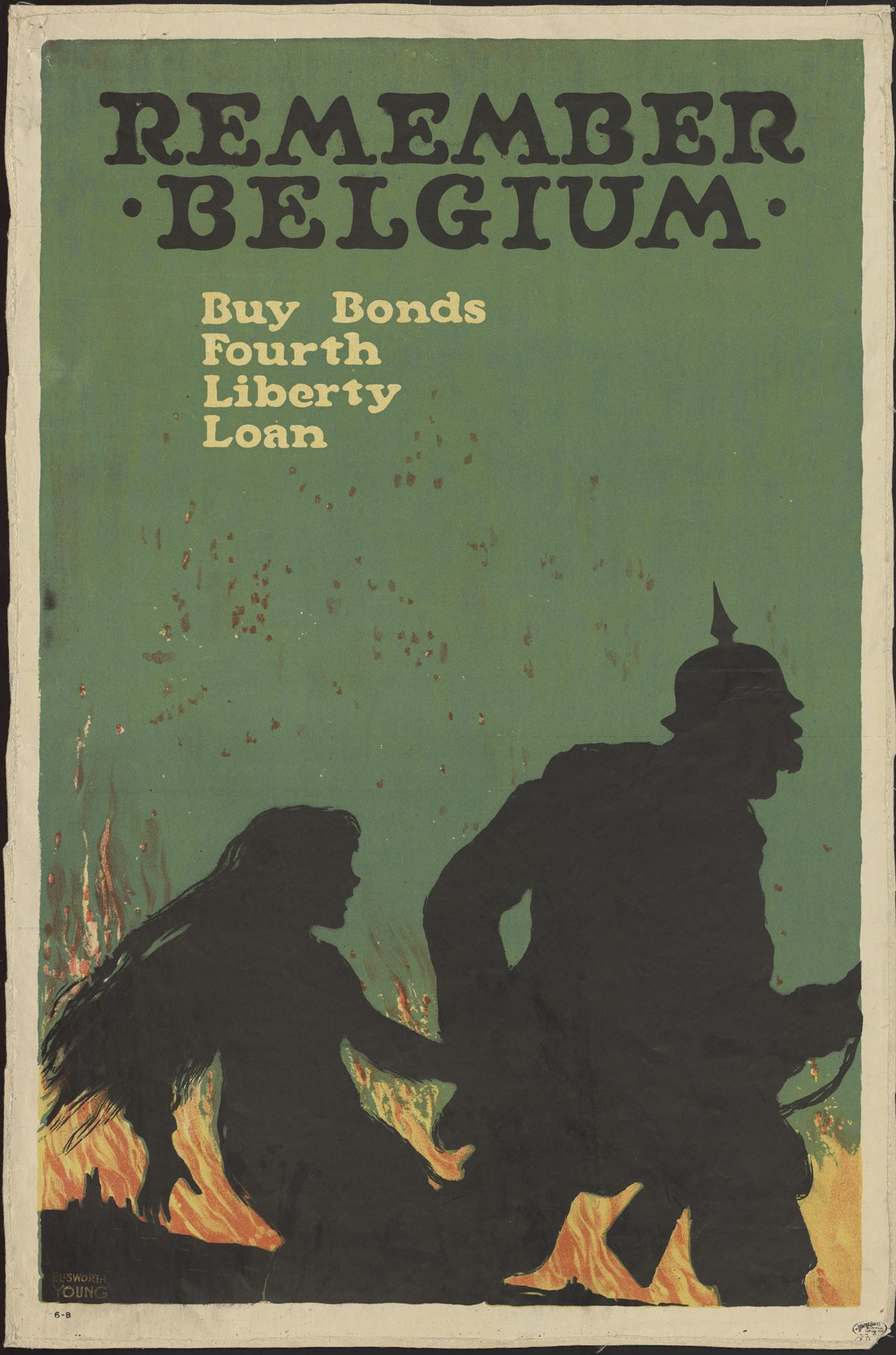

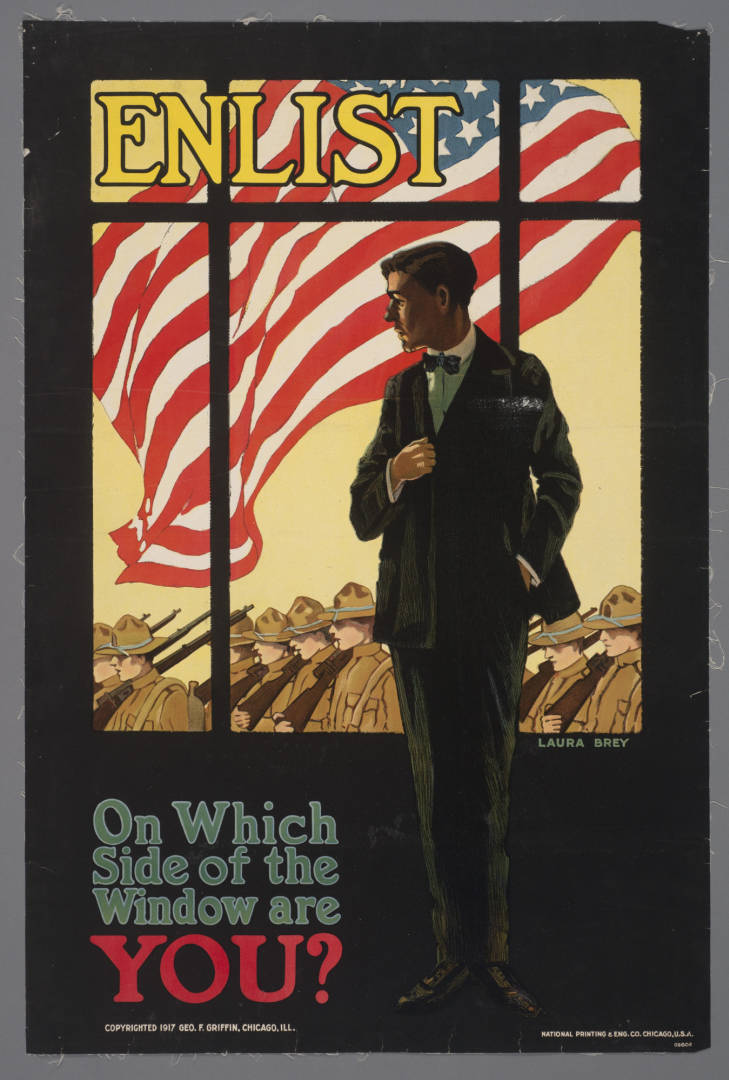

At first, President Woodrow Wilson wanted an all-volunteer army. Posters from the beginning of the war show the government using radicalized caricatures of “the Hun,” appeals to national and masculinist pride, and the defense of a feminized liberty, and civilization itself, to alarm, shame, and motivate. James Montgomery Flagg’s now infamous image of Uncle Sam pointing sternly and declaring “I want YOU for the U.S. Army” dates from this period. Such posters “sold the war,” says David Mihaly, curator at the Huntington Library Art Collections in San Marino California. They “inspired you to enlist, to pick up the flag and support your country. They made you in some cases fear an enemy or created a fear you didn’t know you had.”

But the efforts fell short. Six weeks into the war, only 73,000 men had volunteered. Wilson was forced to accept the recommendation of Secretary of War Newton D. Baker to institute a draft, putting in force the Selective Service Act of 1917. “For the first time in its history,” notes the Library of Congress, “the nation’s military would be derived largely from conscripts rather than volunteers.” While efforts aimed at spurring recruiting continued, the main focus of propaganda on the home front shifted to inspiring maximal support for the war, making sure everyone fell in line and did their part.

War posters from the period are not subtle, their messages unambiguous, the lines between good and evil drawn in thick, black ink. The roles assigned to men and women were similarly rendered. Artists used sexualized images of young women in uniform to sell enlistment, mock the idea of women in combat, and imply the necessity of getting men into those uniforms. Posters like “Gee!! I wish I were a Man. I’d join the Navy” tell their target audience to “Be a man and do it.”

Lady Liberty appeared in various guises, in one poster sternly pointing like Uncle Sam and telling Americans “YOU buy a Liberty Bond lest I perish.” Homemakers on posters urged women on to farming, canning, and knitting. Damsels in peril suffered at the hands of the monstrous Germans. The pathos of women and children in peril made the buying of war bonds an urgent humanitarian act. Images like that of a decapitated Statue of Liberty, surrounded by German biplanes, “exploited the population’s deepest fears,” George Dvorsky writes at Gizmodo.

The posters “symbolize the merging of patriotism and advertising in the United States,” say the Bruce Museum‘s Elizabeth D. Smith. They brilliantly illustrate techniques that influential theorists of propaganda like Walter Lippman and Edward Bernays would elaborate in the coming years for manipulating public opinion and managing a consumer economy with mass psychology. Although most World War I propaganda is “seriously lacking in nuance,” as Dvorsky puts it, it often succeeded where it did because of its shockingly obvious nature.

As Bernays wrote in his seminal 1928 book Propaganda, “the manipulators of patriotic opinion made use of the mental clichés and the emotional habits of the public to produce mass reactions against the alleged atrocities, the terror and the tyranny of the enemy.” The job of propagandists after the war—the ad man, the government bureaucrat, and all “intelligent persons” in what Bernays called the “invisible government”—was to “ask themselves whether it was possible to apply a similar technique to the problems of peace.” His solution: ever more refined forms of the same types of psychological manipulation. Or as he put it, “touch a nerve at a sensitive spot and you get an automatic response from certain specific members of the organism.”

See dozens more World War I propaganda posters at the UT Austin Harry Ransom Center’s digital collections.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.