Claridge’s and Benito Mussolini

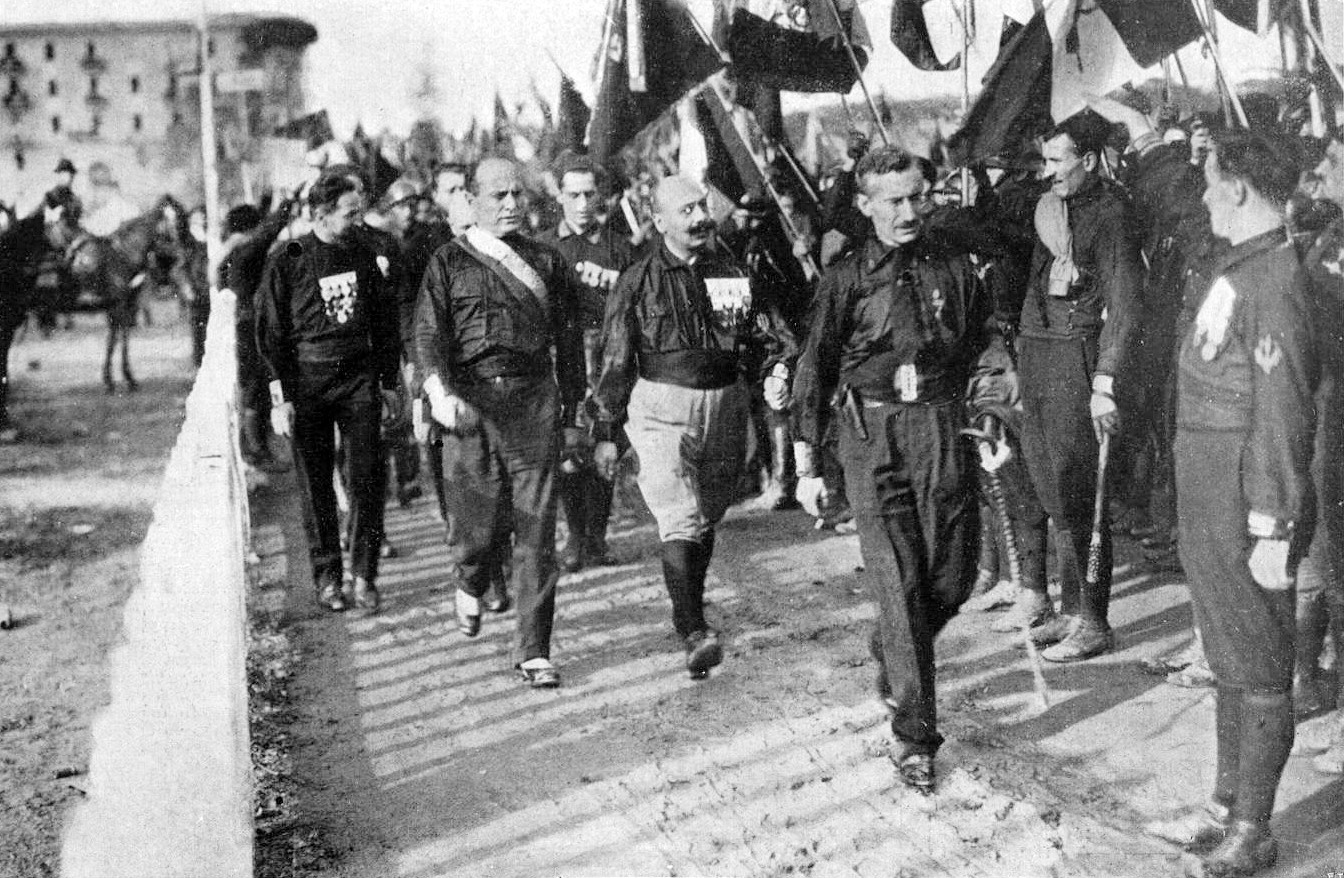

Six weeks after the March on Rome, after which King Victor Emmanuel III had subsequently made him Prime Minister of Italy, Benito Mussolini made a trip to London for an Allied conference on German reparations.

The man of elemental force arrived at Victoria Station on 9 December, apparently on time, and was met by about fifty black-shirted supporters. The Manchester Guardian, like many newspapers of the time, found the uniformed fascists faintly amusing and actually had to explain what his black-shirted supporters were doing when they ‘held high their right arms, with the hands spread slantingly forward’. The correspondent thought all the energetic marching about was to do with the cold, and was worried that the thin ‘black shirt (accompanied by a black tie, some war medals, and a black cloth cap shaped like a fez with a tassel and cord) looked poor comfort for eleven o’clock on a slightly foggy December night’. He then described how the Blackshirts started singing the Italian Fascist marching song ‘Giovinezza’. This was all repeated half an hour later outside Claridge’s Hotel, where Mussolini and his entourage were staying. In fact, during his entire stay and wherever he went, organised groups of Blackshirts greeted him and causing much annoyance to many, sang the same fascist marching song again and again.

As mentioned Mussolini’s choice of hotel was Claridge’s on Brook Street in Mayfair but as soon as he had arrived a loud and unseemly row broke out when the Italian delegation accused the hotel of allocating far better rooms to their French counterparts. No one quite knew what to make of the young Italian leader. In London he wore spats, a butterfly collar with a top hat and badly pressed striped trousers. The aristocratic British Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, remarked: ‘He is really quite absurd.’ Most people were also surprised by Mussolini’s height (he was only 5 feet 6 inches).

The next day, Mussolini and his party, all wearing Fascist party badges, were received at Buckingham Palace by the king. Later, the Italians all drove to the Cenotaph in Whitehall, where Signor Mussolini laid a wreath of remembrance at the foot of the monument. Finally, they visited the Italian Fascist HQ at 25 Noel Street. At one point during the trip Mussolini missed a press conference because he was sleeping with a prostitute back at the hotel. During his stay he complained incessantly about the fog, which he insisted penetrated into Claridges, his clothes, his bedroom and even his suitcases. When he returned to Italy he swore that he would never return to England, and he never did.The Pax

November 1922: Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945). (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The New Earl’s Court Hotel and the Killer of Dr Martin Luther King

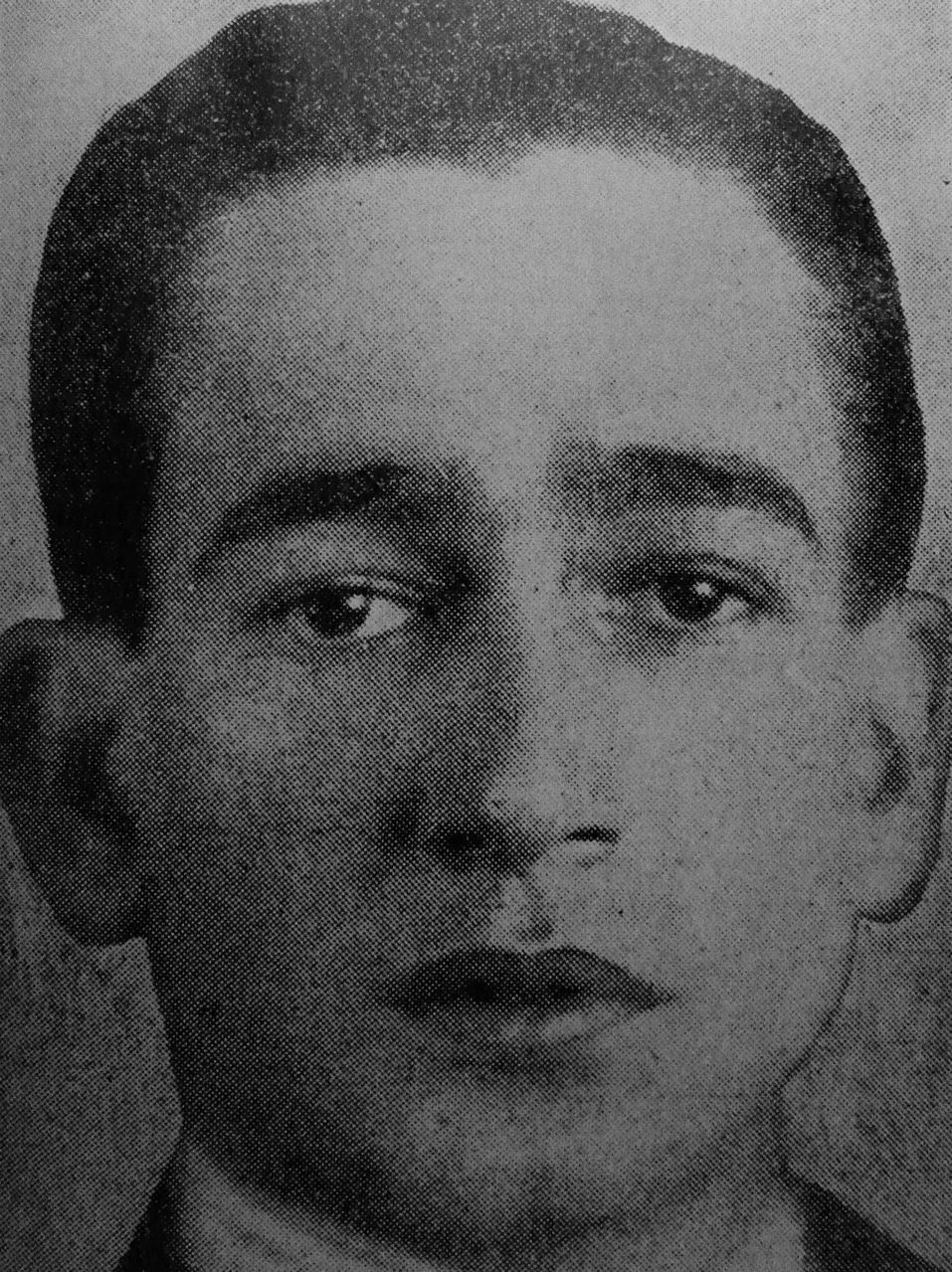

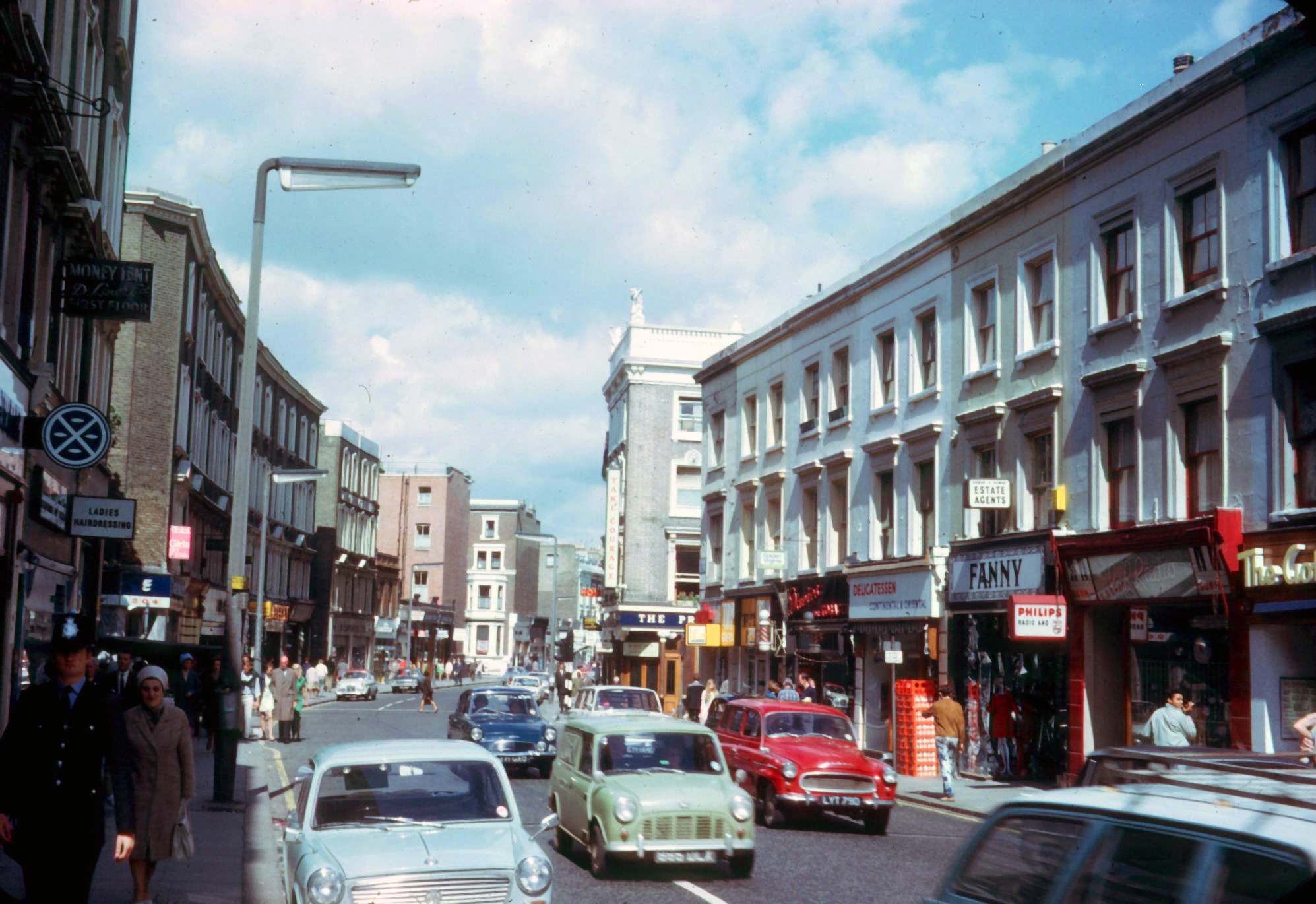

On 17 May 1968 and about six weeks after he had shot and killed Dr Martin Luther King in Memphis, James Earl Ray, via Canada and Portugal, arrived in London. He found anonymity in Earl’s Court and Victoria – at the time both run-down areas of London and full of boarding houses and cheap hotels.

Earl’s Court was an area of London known after the war as the ‘Danzig Corridor’ due to the number of Polish people who had settled there. In the late forties there were 38,000–40,000 Poles living in and around London, then the largest foreign-born community in the capital. Twenty years later Earls Court was more likely to be called ‘Kangaroo Valley’ because of the large number of transient Australian and New Zealand travellers living there. At the time it was one of the cheapest areas to stay close to central London. There were also hundreds of cheap and seedy hotels and hostels, so it was the perfect part of London to stay relatively anonymous. In 2015 Heathfield House is still a hotel but it is now called the Rockwell and any contemporary assassins needing a single room in 2021 (pandemic allowed) would have to pay around £150 per night.

Earls Court Road in 1968 – photo by Bill Holmes

Ray stayed at Heathfield House for ten nights and after checking out walked down to the New Earl’s Court Hotel at 35–37 Penywern Road, less than half a mile away. Penywern Road was a particularly shabby and run-down street in those days and the hotel, like the rest of the terrace, was made of London brick with the rendered parts covered in peeling, dirty white paint. Above the door was a blue awning. The receptionist at the hotel was called Jane Nassau and she remembered Ray staying there: ‘He was extremely shy, pathetically shy,’ she said. ‘He signed in as Canadian. But I thought it was strange. He had this deep southern drawl. He was extremely nervous.’ She also remembered explaining the British currency, which had become even more confusing for a foreign traveller as some new 5p and 10p coins had been introduced a month or so before: ‘But he was a bit thick. It didn’t sink in.’

Ray decided to check out of the New Earl’s Court Hotel and told Jane Nassau, falsely, that he was leaving for the airport. It was now raining heavily and clutching his bags Ray went out looking for another room. He initially tried the nearby YWCA at 118–120 Warwick Way, but although it did have rooms for men, it was full and he was directed to the nearby Pax Hotel three doors down the same road at number 126. The Pax Hotel was then really a private house but its owner, Swedish-born Anna Thomas, let out several rooms and there was a small sign that simply read ‘Hotel’ hanging down from a small first-floor balcony. The building is now called the Bakers Hotel and a single room there in 2015 is around £100 per night.

When Thomas opened the door of her hotel Ray was standing there, dripping wet in a beige raincoat, a suitcase in one hand and books and newspapers under his other arm. He introduced himself as Sneyd and said that he would take a room.

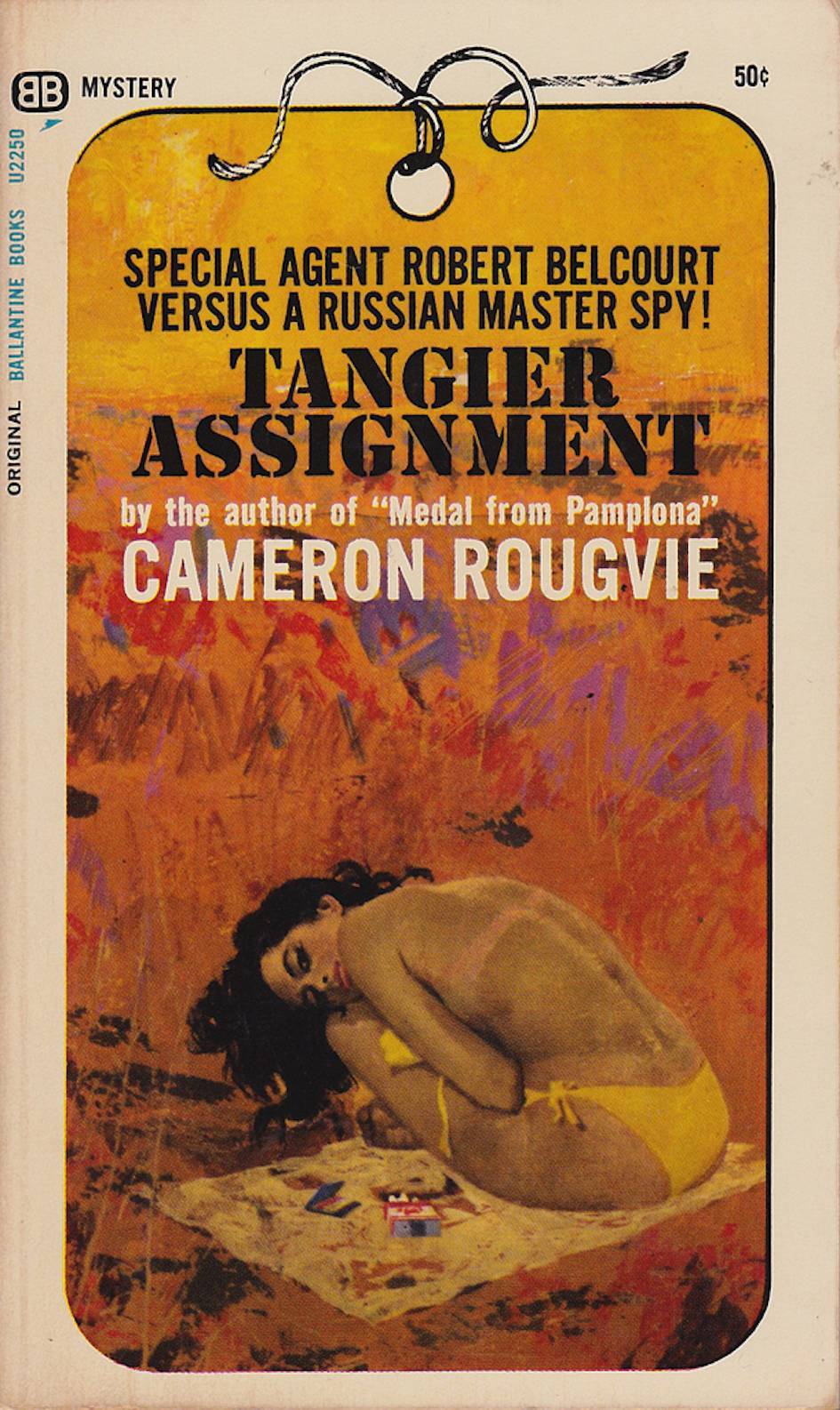

At 9.30 a.m. on Saturday 8 June, Anna Thomas knocked on ‘Ramon Sneyd’s’ room and found that her tenant had packed up and disappeared. The room had been left clean except for a newspaper that featured Robert Kennedy’s assassination that had taken place two days before. The day after Martin Luther King had died, Robert Kennedy made a speech where he said ‘no martyr’s cause had ever been stilled by an assassin’s bullet’. Ray had also left behind a Cold War spy thriller called Assignment Tangier by Cameron Rougvie.

Assignment Tangier by Cameron Rougvie, the book left behind by James Earl Ray

The bright, lurid cover featured a cross-legged woman in a yellow bikini, the top of which was draped undone. The blurb talked of ‘international intrigue, Mafia villainy and free-booting contrabandists, helped by the lovely Sandra Grant’. Inside the back of the book was a mass of figures where Ray had tried to compare the value of dollars to pounds. In the sink, crammed down the spout, was a plastic syringe.

Thomas would later say that she was quite glad to see Ray leave: ‘He was so neurotic, such a strange fellow. I felt sorry for him but he was so obviously a troubled man that he gave me the creeps.’

At Heathrow a suspicious immigration officer noticed Ray had two passports and said: ‘I say, old fellow, would you mind stepping over here for a moment?

Ray was found to have a loaded revolver stuffed in his back pocket and when asked why replied: ‘Well, I’m going to Africa and I felt that I might need it. You know how things are, out there.’ He was immediately arrested and 40 days later extradited back to the USA.

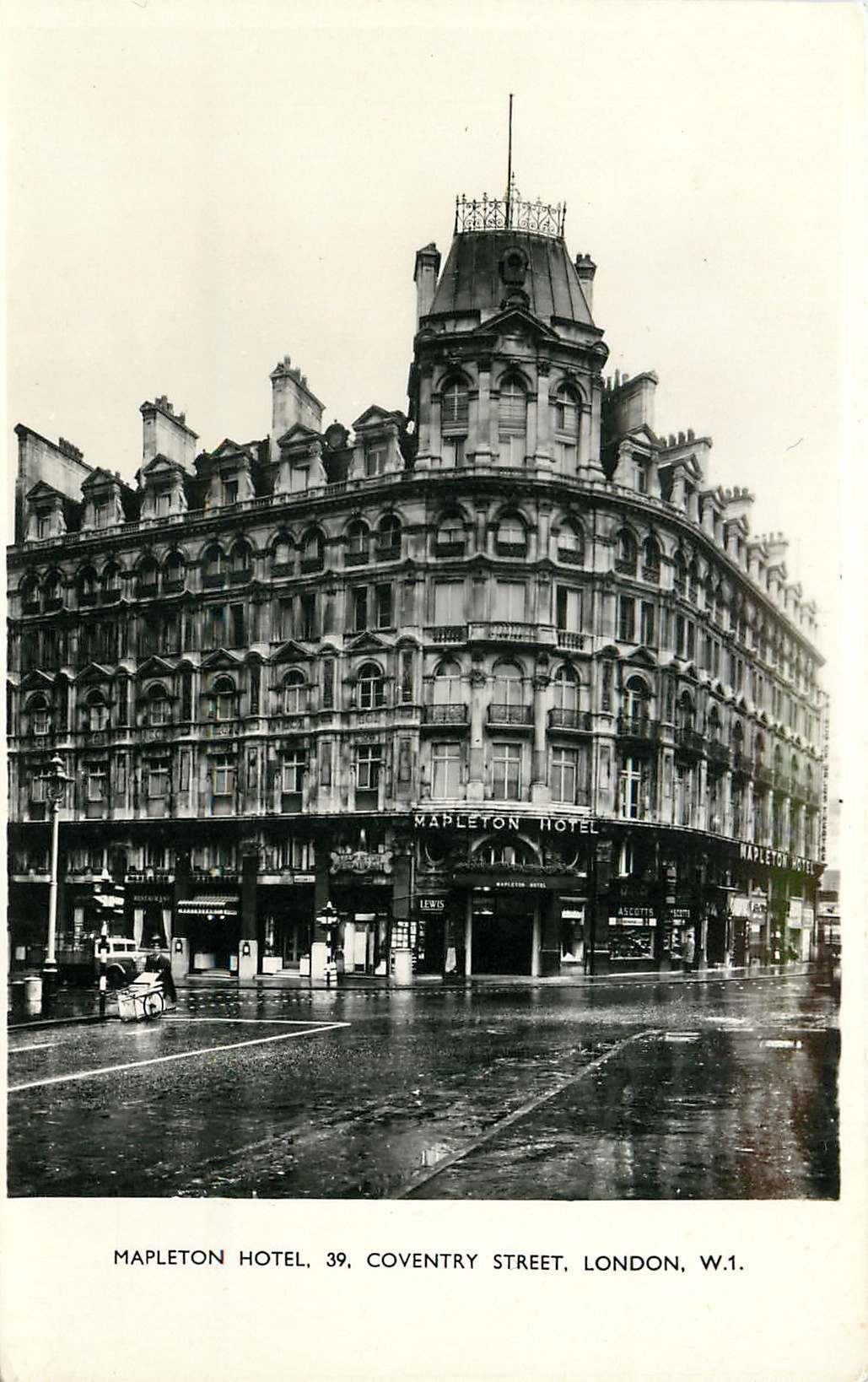

The Mapleton Hotel on Coventry Street and Barbara Windsor at the Flamingo Club

Mapleton Hotel c. 1952

A 21-year-old ’30 shillings a night’ pianist called Jeffrey Kruger thought the basement of the 100-room Mapleton Hotel on Coventry Street (now the Thistle Piccadilly) would be perfect for his idea of a new kind of jazz club.

He had always wondered why places catering for jazz were always a bit of a dive and once explained the strict door policy for his club which he called the Flamingo: ‘No man can be admitted without a necktie and no girl is welcomed who looks like a refugee. It is possible and preferable, I think, to be hip and keep a high social standard.’

In 1954 Billie Holiday played at the Flamingo wearing the same gold dress she had worn at the Royal Albert Hall earlier that evening and was accompanied by Ronnie Scott on saxophone. A year later Ronnie held some auditions at the Flamingo.

His singer, Annie Ross, was ill and he needed a replacement for two weeks. After all the hopefuls had tried out he pointed at a short 18-year-old East End girl and said: ‘You. Little one. Outside the Mapleton Hotel, Leicester Square. Monday morning. Nine o’clock.’

27th May 1955: English actress Barbara Windsor with Patricia Start, a fellow student at the Aids Forster Dancing School on a fairground ride at the Battersea Festival Gardens, London. (Photo by John Pratt/Keystone Features/Getty Images)

At the time Barbara Windsor couldn’t work out why she had been chosen when so many other better, more experienced singers had been auditioned but Ronnie Scott thought she was perfect. Although for some reason he always insisted she played the maracas while she sang.

A year after Windsor’s short stint as a jazz cabaret singer, the Flamingo Club moved premises to Wardour Street, the location where it made its name.

The Woman Who Got Away with Murder at the Savoy

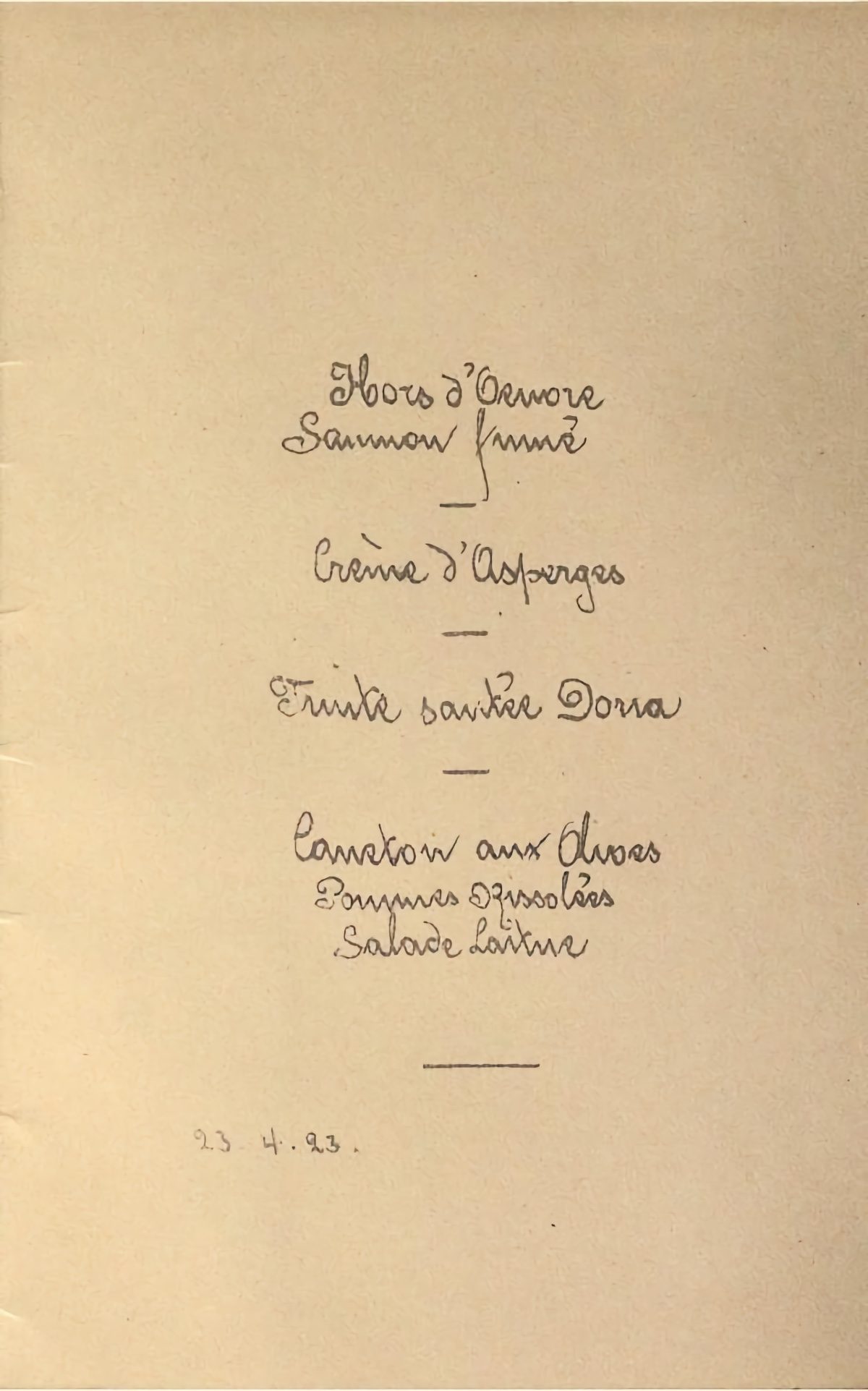

On July 1 1923 Ali Kamel Fahmy Beh, one of Egypt’s richest men, booked into a suite of rooms on the fourth floor of the Savoy Hotel. He was accompanied by his beautiful French wife Marguerite, once a Parisian courtesan and a former lover of the Prince of Wales.

Eight days later at 2.30am, after a late supper in the restaurant during which the couple loudly and aggressively argued, Marguerite Fahmy shot her husband dead in the hotel corridor.

Savoy Menu 1923

The night porter ran to the scene where he found, next to the door of room 42, Fahmy crumpled against the wall surrounded by a large pool of blood. Marguerite dropped a large and heavy hand gun and then stumbled towards to the porter saying over and over again in French – ‘what shall I do? I’ve shot him’.

Two months later at her trial at the Old Bailey Marguerite was defended by the Edward Marshall Hall who presented Marguerite to the jury as the victim of “brutality and beastliness” from her “oriental husband”.

The trial judge forbade any mention of Marguerite’s less than innocent past while in his summing up described Fahmy as “a monster of Eastern depravity and decadence, whose sexual tastes were indicative of an amoral sadism towards his helpless European wife”.

The jury took only an hour to return the verdict ‘not guilty’ and Marguerite was acquitted of all charges.

The Daily Chronicle wrote that the verdict was ‘one of those cases, so rare in English law, of justifiable and excusable homicide’. Marguerite Fahmy had got away with murder.

Marguerite, despite a court in Egypt rejecting her claim to her husband’s property, lived in luxury in an apartment facing the Ritz in Paris until the end of her life. She died at the age of 80 in January 1971.

Madame Fahmy

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.