If human nature could be altered with revolutionary design, Buckminster Fuller might have been the man to do it. Not only was he an architectural and engineering visionary, but he also seemed primarily motivated by altruism, with a vision for the future that included a high quality of life for everyone rather than a handful of inventors and investors. He foresaw and urgently sought to avert the situation we find ourselves in now: diminishing natural resources, ecological collapse, unsustainable over- production and consumption.

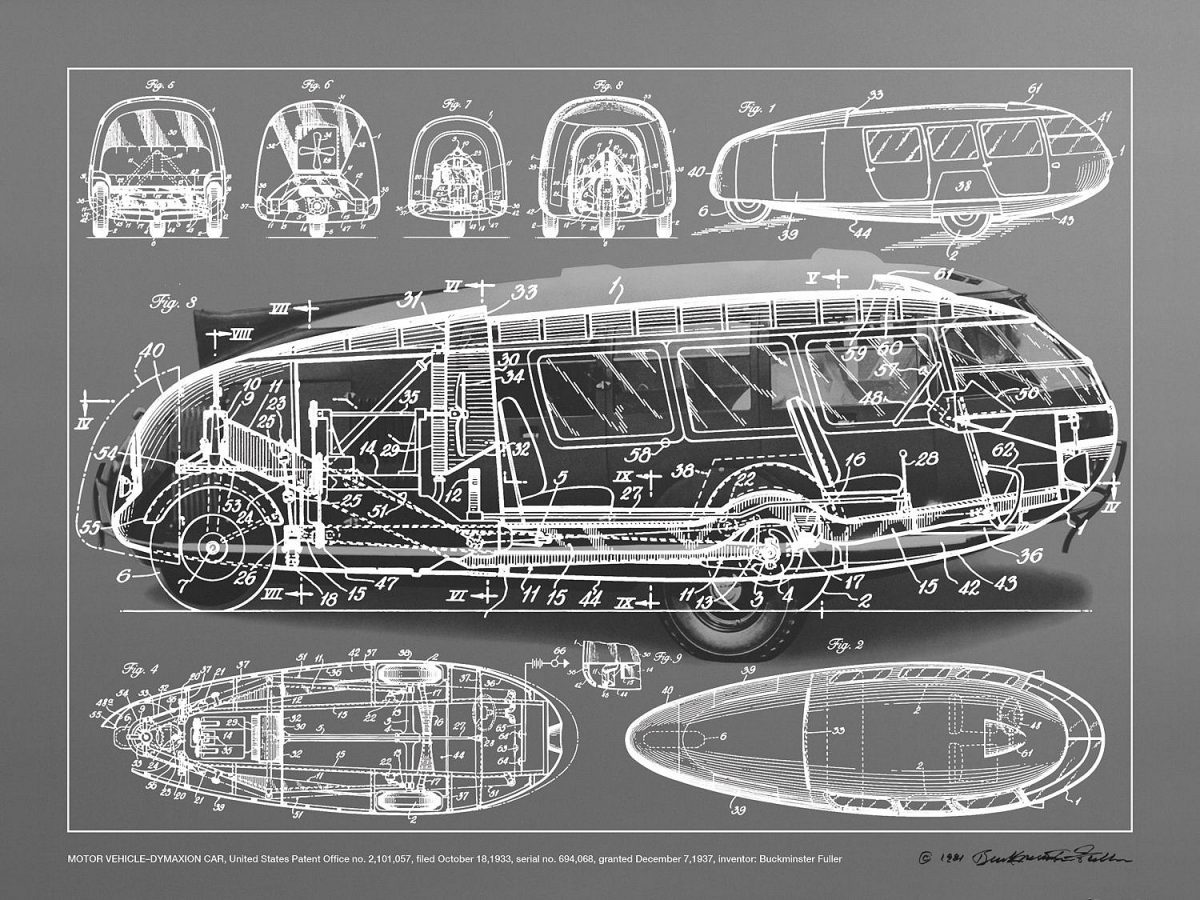

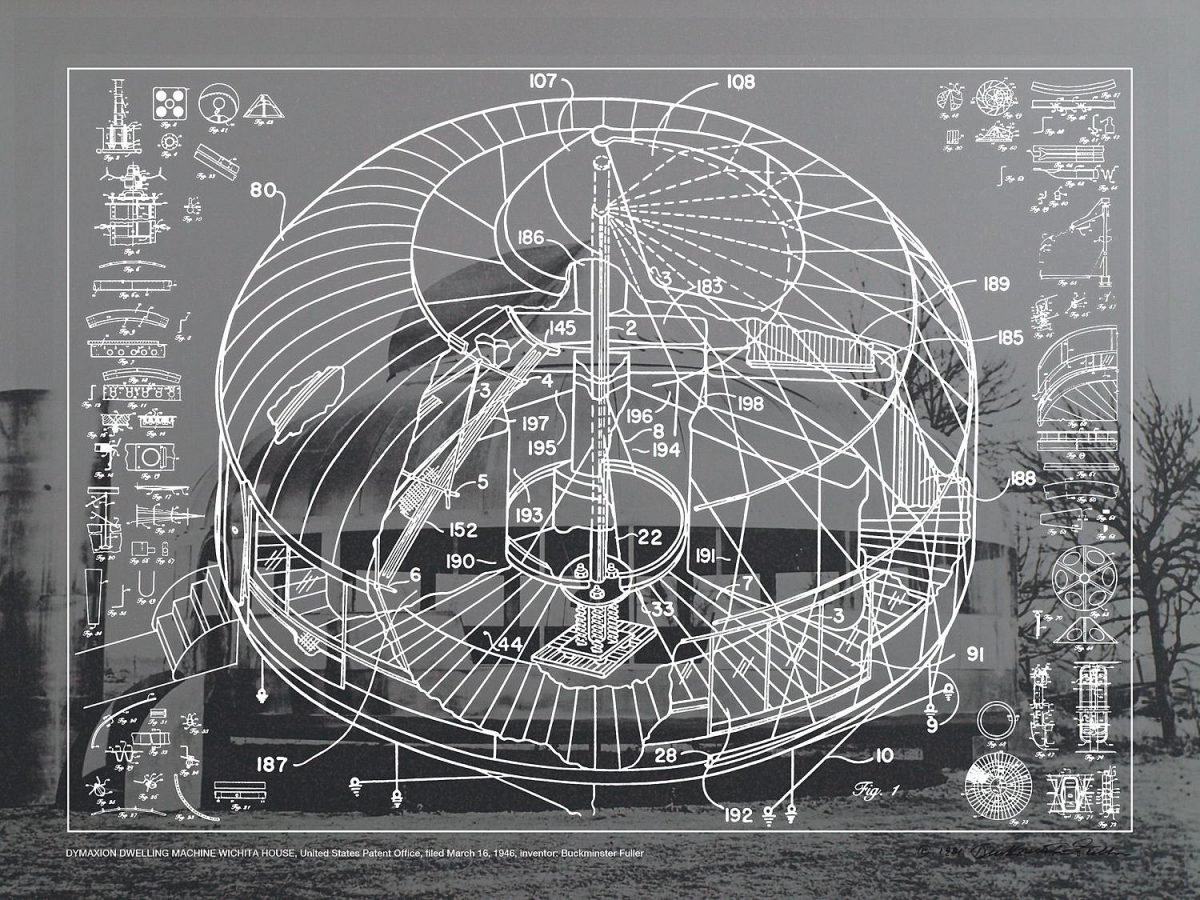

Buckminster Fuller applied his Dymaxion brand name—a portmanteau of “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “tension—to everything from houses to maps to cars. Some of these products were more successful than others. He mastered the problem of too much sleep cutting into his inventing time with the “Dymaxion sleep system.”—for two years, he slept two hours a day in short intervals. He reported “the most vigorous and alert condition that I have ever enjoyed,” but he had to give it up because his colleagues could not adapt.

His theories are marked by neologisms like “tensegrity,” “ephemeralization,” and “omni-interaccomodative,” terms that do not populate the typical architect or engineer’s lexicon. For much of his early career he was treated as a fringe figure, if not a crackpot, by established designers, though by the sixties he was discovered and embraced by hippies and New Age back-to-the-landers, as well as the designers of playground equipment and the Expo 67 United States Pavilion in Montreal.

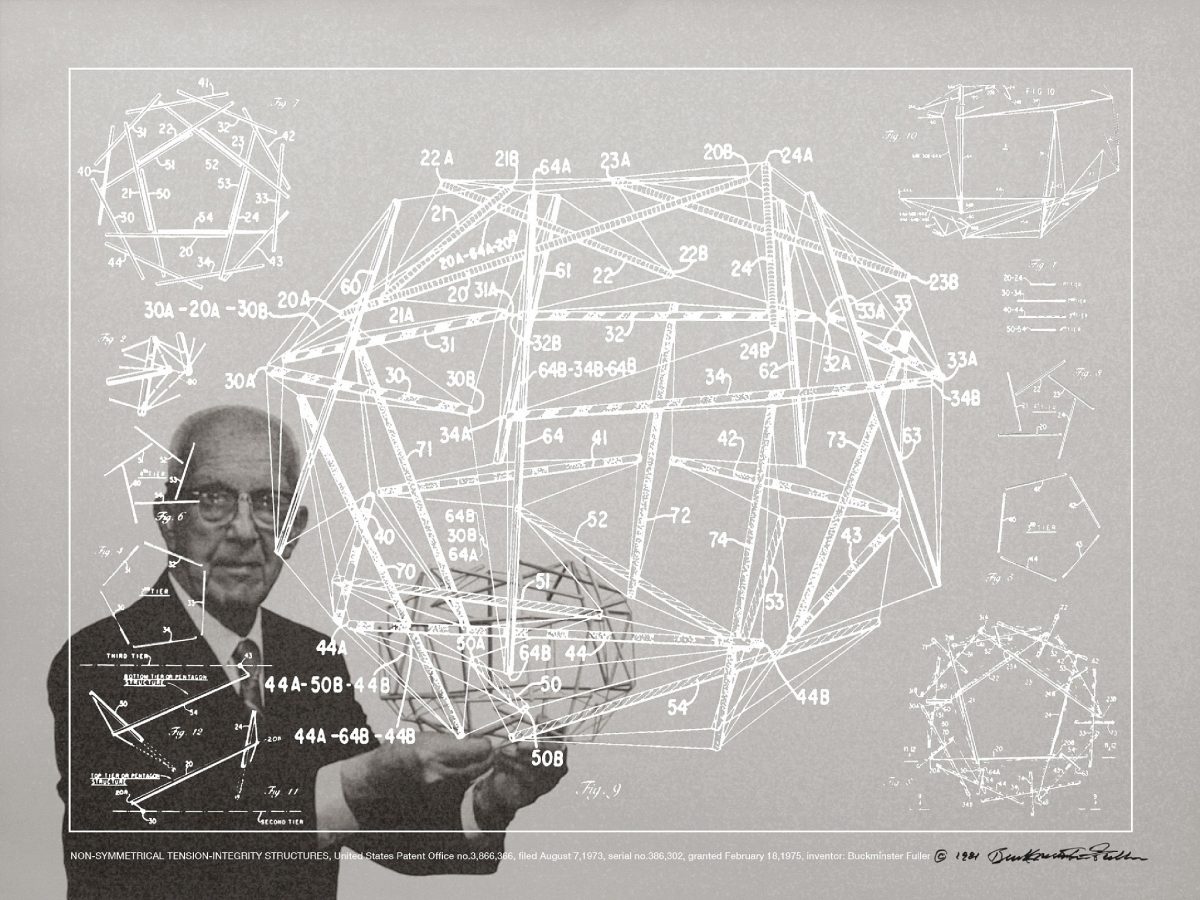

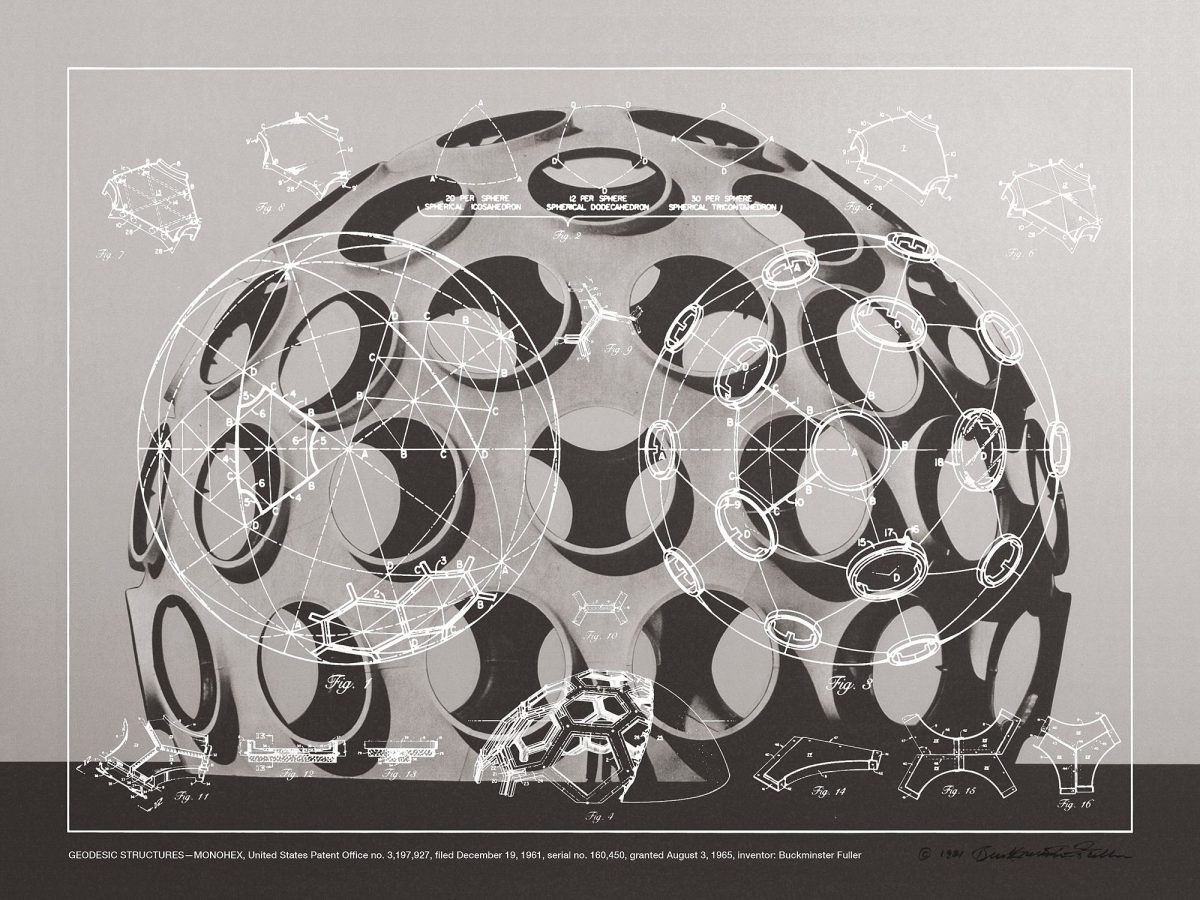

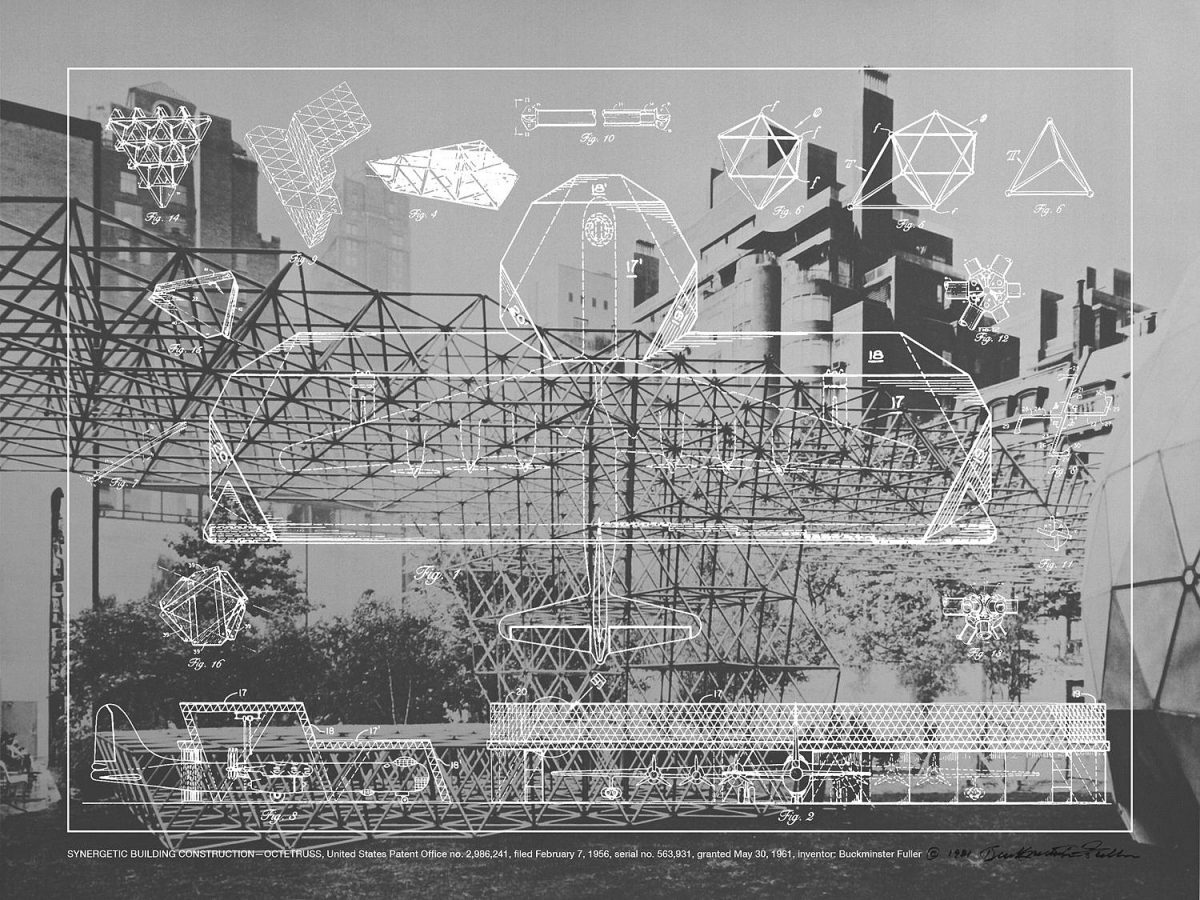

Maybe we’re starting to catch up to Fuller again. His geodesic dome—once a 60s symbol for forward-thinking design and de rigueur for utopian communities in the 70s—is making its way back in tent form. He’s had posthumous exhibitions at the Whitney and SFMOMA. And the Edward Cella Art & Architecture Gallery in L.A. is showing the promotional posters he created with Carl Solway in 1981. The posters show detailed schematics overlaid atop photos of real-life realizations.

“Striking with their two-layer design,” writes Katharine Schwab at Fast Company, the posters “are Fuller’s homage to his own genius—and an attempt to bring what he believed were world-changing utopian concepts to the masses.” Called simply Inventions, the series of 13 images “visualize what Bucky’s accomplishments were for a wide range of audiences,” says Cella. “Bucky could speak to engineers, to architects, to cartographers, but he also believed it was really important to communicate to the general public.”

Fuller died in 1983. One wonders what he would have done with social media. See more of his designs here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.