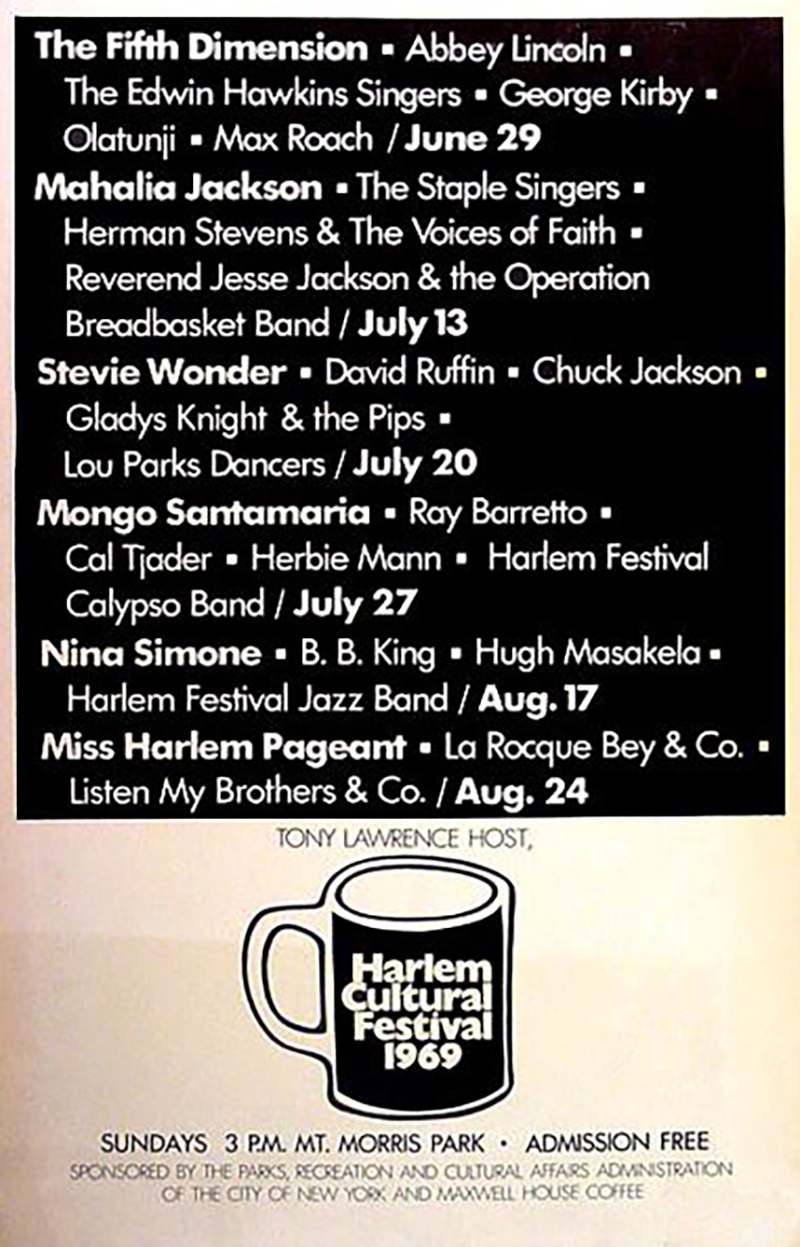

Away from the “peace and love” at Woodstock in 1969, New York City’s Harlem was the venue for a series of shows that became known as Black Woodstock. Held at 3pm on Sundays in Mount Morris Park between 29 June and 24 August, 1969, as many as 300,000 people attended the festival headlined by B.B. King, The Staples Singers, Mahalia Jackson, Nina Simone, Gladys Knight, Stevie Wonder and Sly & the Family Stone.

While Woodstock was marked in an Oscar-winning documentary, The Harlem Cultural Festival was only broadcast as two one-hour highlights shows on a local New York TV station and never repeated.

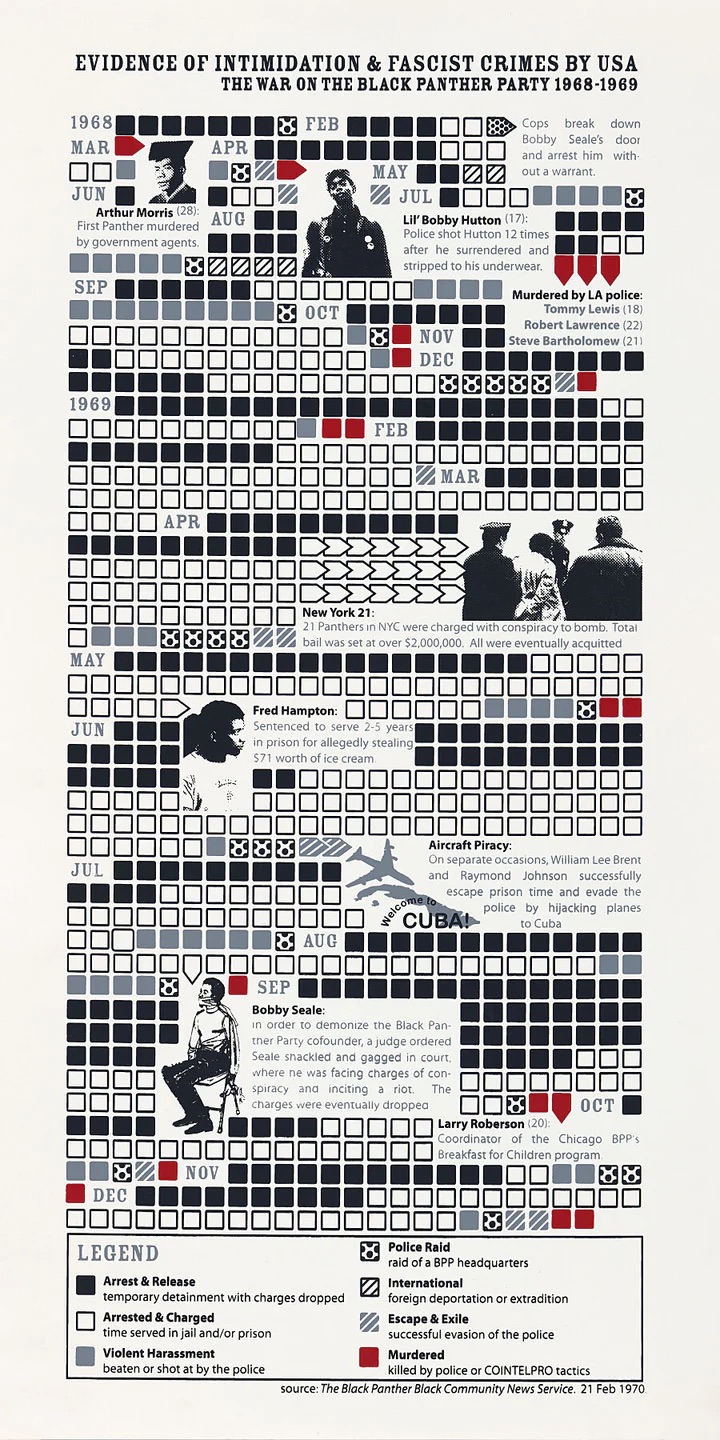

The time was turbulent and violent. The concerts came not long after the murder of Martin Luther King (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) and the riots in Watts. The NYPD refused to provide security for the Harlem Festival, which was provided instead by the Black Panthers, some of whom had been indicted of a bombing campaign across Manhattan – earlier that year, five sticks of dynamite had been found behind a local precinct house; two years later, all 21 defendants were acquitted.

So Black Woodstock wasn’t just about the music. The mood was perhaps best summed by Reverend Roebuck Staples (December 28, 1914 – December 19, 2000), of the Staple Singers, who addressed the crowd during the band’s performance:

“You’d go for a job and you wouldn’t get it. And you know the reason why. But now you’ve got an education. We can demand what we want. Isn’t that right? So go to school, children, and learn all you can. And who knows? There’s been a change and you may be President of the United States one day.”

Black Woodstock Will Not Be Televised

The Harlem Festival was filmed by television producer Hal Tulchin, who hoped to sell the footage to the networks. “It was a peanuts operation, because nobody really cared about Black shows,” said Tulchin in 2021. “But I knew it was going to be like real estate, and sooner or later someone would have interest in it.”

None of the networks were interested. The odd snippet has been sneaked on to You Tube, and Nina Simone licensed film of her performance for a DVD release, but why the whole concert has never been released or even shown on TV is shaming indictment on America’s media. As Alan McGee asked in 2020:

Why is Black Woodstock still sitting in the vaults? For me, this is not just a concert, but a valid historical document capturing the height of the black power movement, positivism and the tension within their community. I remember a poignant Simone quote from 1997 when asked why she left the US: “I left because I didn’t feel that black people were going to get their due, and I still don’t.” It’s hard to disagree with her when a cultural event as significant as Black Woodstock has been gathering dust in a vault for over forty years.

Black Woodstock: The Summer of Soul

In 2021, a new documentary of the festival, The Summer of Soul aired. The film’s director Ahmir Thompson, aka Questlove, said The Harlem Cultural Festival being forgotten about is part of “the all-too-common erasure of black history”.

“The Harlem Cultural Festival was an event thrown by two gentlemen, Tony Lawrence [who booked the acts] and by Hal Tulchin [who filmed it],” he told the BBC. “They somehow managed to gather some of the mavericks of their day. We’re talking about Stevie Wonder. Nina Simone, Sly and Family Stone, Ray Barretto, Olatunji, Hugh Masekela, Edwin Hawkins Singers, BB King, comedians, politicians, everybody was there.

“The event is preserved professionally on tape and not one producer or outlet is interested in seeing the footage or making it worldwide-known or distributing. So, what winds up happening is that this film just sits in the basement for 50 years.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.