In 1921 reporter Genevieve Forbes Herrick (1894-1962) disguised herself as an immigrant to expose conditions at Ellis Island for a series of articles in the Chicago Tribune. She “ran the gantlet of all the terrors of this great American gateway to the United States,” her paper wrote, “and she will disclose what she and her fellow immigrants endured to enter this country.”

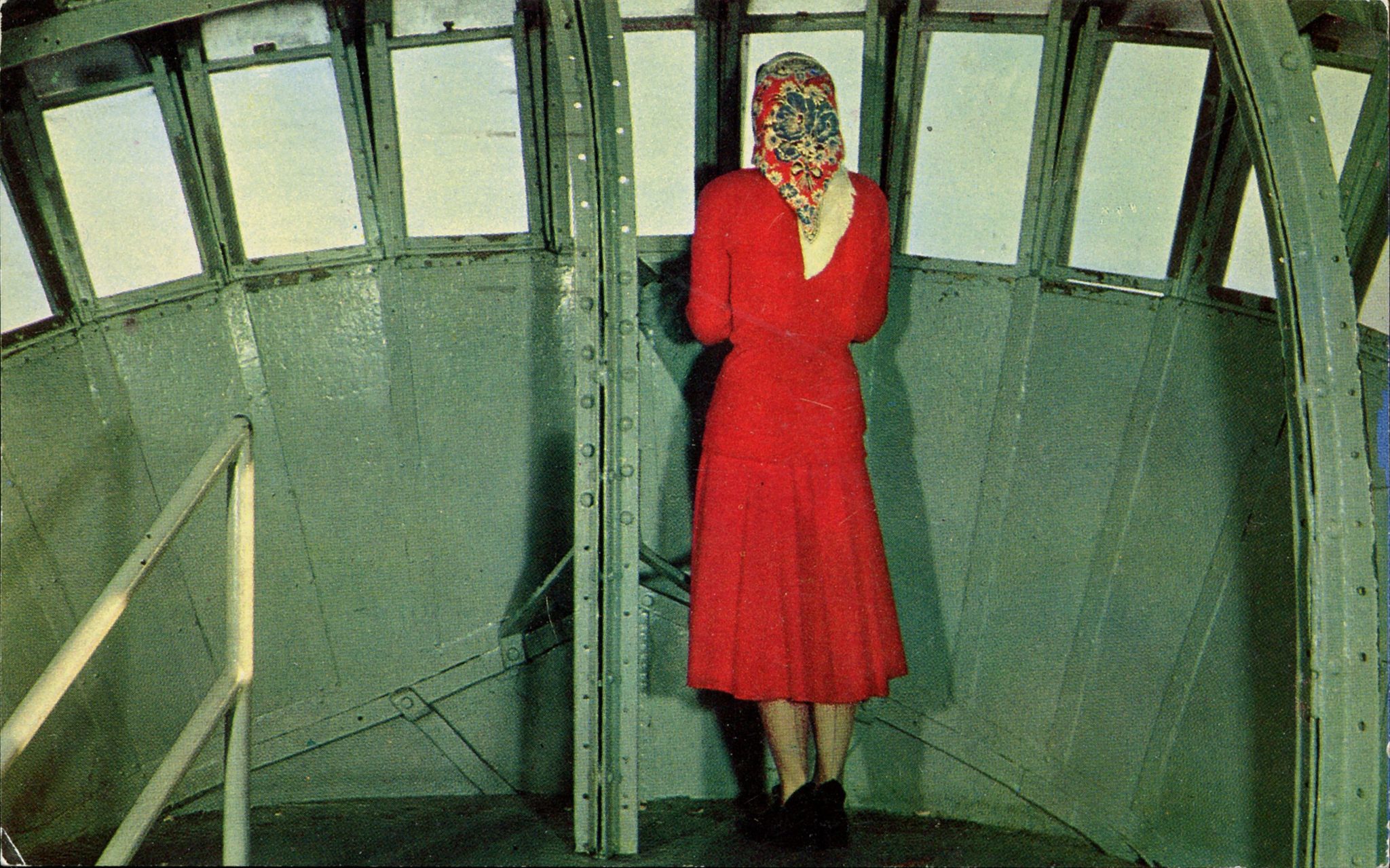

The first lesson for would-be Americans was that there place was ‘looking up’, wrote Herrick – “Up at the officials, who quiz you, scorn you, disregard you, threaten you; up at the first-class passengers who gaze down from their deck with well-bred politeness at those ‘quaint people’.”

A graduate from Chicago’s Lakeview High School, in 1916 Herrick earned her bachelor’s degree from Northwestern University, where she was the first woman editor-in-chief of the school’s daily; and the following year earned her master’s from the University of Chicago. After teaching high school English for a year, she joined to the Chicago Tribune in 1918 as assistant to the exchange editor. In October 1921 she made a splash with her thirteen-part expose of the United States immigration service. She had gone to Ireland and then returned, posing as an immigrant. Her articles and testimony provided the basis for a House investigation of Ellis Island.

Ellis Island immigrant – c. 1910 “Laplander.” Via

Immigrants to the US have always been treated with suspicion. One of the founders of the Republic, Alexander Hamilton, wrote: “To admit foreigners indiscriminately to the rights of citizens, the moment they put foot in our country… would be nothing less, than to admit the Grecian Horse into the Citadel of our Liberty and Sovereignty.”

Fast forward to the words of President Trump, and his views on immigration: “The time is overdue to develop a new screening test for the threats we face today. I call it extreme vetting. I call it extreme, extreme vetting.”

When Genevieve Forbes Herrick launched her investigation, the ‘huddled masses’ had few champions. They’d paid their fare. They were not charity cases. They were treated as pariahs and deserters. They were without power. But Forbes had power. She had an audience. She would record the treatment meted out to immigrants at Ellis Island and reveal all to her fellow Americans.

The New York Post set the scene:

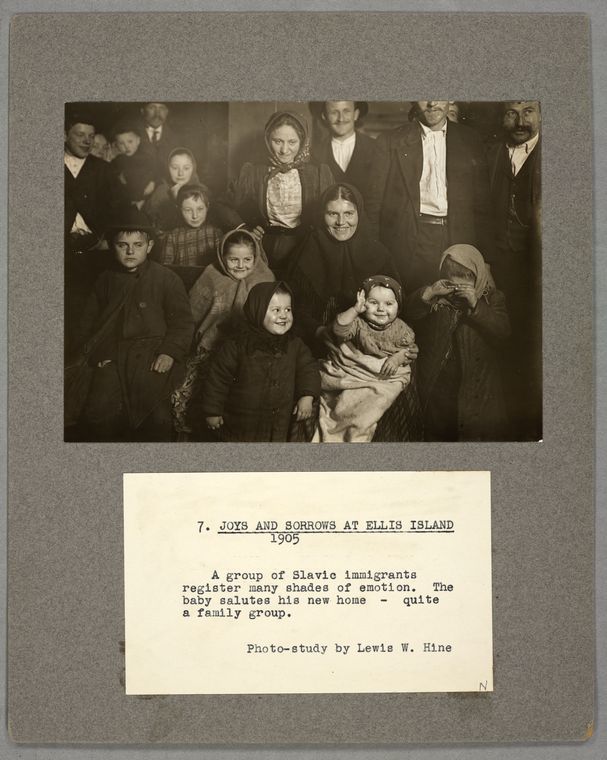

It was not that reasonable souls objected to immigrants per se, only to unrelieved hordes of them, and once Congress imposed emergency quotas in the summer of 1921 and the floods began to ebb – probably, in truth, just in time to avert a grave industrial depression – it became possible to resume thinking of the newcomers not as locusts blackening the sky, but as pilgrims come with human faces and hopeful human hearts. Soon the newspapers were clucking once again over every lost little girl sniffling at the great gateway to the golden shore, her relatives misplaced, her bag and dolly stolen.

By fall, as reasonable souls began remembering what a grim place Ellis Island had always been, even when run by reformers, reporter Genevieve Forbes, writing for the Daily News and The Chicago Tribune, was enroute to Ireland’s County Wexford, there to don a home-sewn blue dress and a pair of heavy clogs and pass herself off as an impoverished young colleen desperate to reach the promised land. She was one of about 700 travelers – Irish, Czechs, Polish Jews – who in October 1921 made an eight-day steerage crossing to the Port of New York and then sat there for several days more, suffering indignities and abuse from the dreadful little officials who ran the island.

In Dublin, the inspections began:

More inspections, examinations, tests. Proof, always proof, now of our integrity, then of our intelligence. Later of our morality and, perhaps the most humiliating of all, of our cleanliness.

The fee for travel?

“One ticket to America, third class, please,” I ask the clerk. “One steerage,” he replies, and it doesn’t sound quite the same. BRITISH passport fee, 40 cents. American consulate fee, $10. Passport photographs, $1.

32. Vaccination, $2. Passage plus head tax, $82.

40. Landing money, $25. Sinn Fein permit, $1. . . .

Travellers were not encouraged to leave.

It is futile to discourage the girls with discussions of low wages in America when these girls have been doing a man’s work on the farms for $5… The Sinn Fein leaders are making every effort to keep the young people in the country..The girls who haven’t been able to get permits are fearful lest the Sinn Fein authorities detain them.

And then the journey:

Four officials stand at the gangway. “Drop your luggage, show your hands,” they yell. The skin of our hands is examined; our hair is examined; we stumble over our cheap suitcases, are bundled over a plank and we are on the tender…

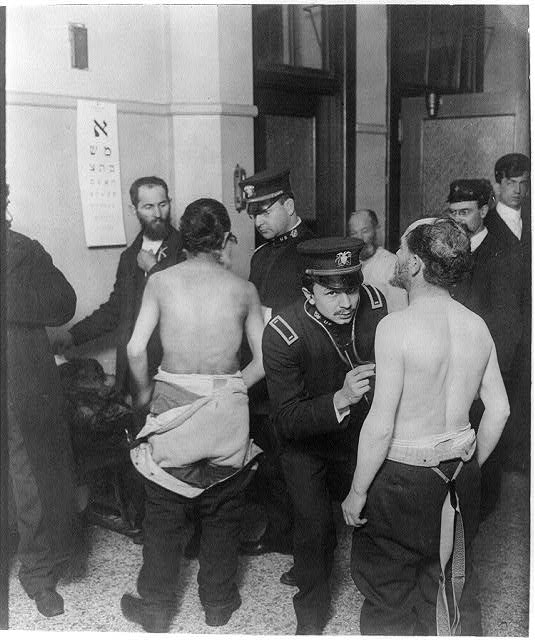

We are packed in the closest of quarters… There is no opportunity for taking a bath… We can’t be always standing… We rather envy the peasants who put down their beds, literally, on the deck and sleep amid dirt, refuse and rain. SOME OF US have been tipped off that the medical inspection is more rigorous for those in the front line. As a result, the end of the line is popular….”Strip to the waist! No monkey business! Do as I tell you and do it now!

“Stand in line! Don’t you understand English?”

“Damn you, stand straight!”

Women are biting their lips to keep back the tears. The old woman next to me is shaking so she can’t hold her clothes in her hand.. Up before the searchlight, shoves, pushes, punches… ”

OF COURSE THEY have to have rules and regulations, but why can’t they treat us as if we were decent?

Even the most stupid of us left our native countries believing in the necessity of laws strictly enforced. But when we see, at the threshold of our new home, petty officials use a bit of gold braid to insult women, shame girls, frighten children…

“Get in line there, what’s the matter with you?”

“Take off your hats, take down your hair, roll up your sleeves!”

“You over there, I’m talking to you! Don’t you understand nothing?”

YELLED AT BY self-important men in uniform, sworn at by subordinates, insulted by workmen, awed by inspectors, frightened by doctors… Five girls have been forbidden to telephone or telegraph relatives waiting for them. The authorities will not release them until their relatives come for them; their relatives will not come for them until the girls send word to them; the officials forbid them in any way to communicate with the outside world. It seems an endless circle. I intimate as much to the inspector. “Say, we don’t need any advice from a smart aleck like you. We don’t need you to butt into our affairs. You think you’re pretty smart? You’re not so damned clever. If you’re not careful I’ll keep you on the island all night.”

“But how can you? My card is marked OK. That means that I am released.”

“I can do just what I please. I don’t care what your card says. One more word from you and I’ll cross out this OK.”

“The girls motion me to be quiet.”

A Syrian Arab at Ellis Island, 1926 Via

They were objectified as the medics set about their work. The ship’s stewards would stand close by and watch.

They pass obscene jests as to the nature of the examination. The older women are indignant, the younger girls semi-hysterical.

Money mattered. With money you could tip the guards to be more lenient. On arrival at Ellis Island, first and second-class passengers disembarked. Third-class passengers were forced to remain on board. After a day and a night waiting, the ‘third -class Colleen’ and her fellow travellers were transferred to another vessel.

The transfer to the small boat, Forbes wrote, required yet another exam in which the women were stripped to the waist and examined behind a small screen. When the inspector was finished, she shoved the half-naked woman onto the open deck “… in plain sight of any male passenger or employee who chooses to look.”

The physical abuse escalated on the smaller boat. Passengers were pushed, kicked and shoved into a single-file line.

Women are biting their lips to keep from crying; the old woman next to me is shaking so hard she can’t hold her hands in her clothes.

Forbes did not hold back, as the Tribune recalls she painted a vivid picture:

Forbes felt helpless. A complaint or a sour look could have meant days in detention or deportation. Standing in the crowd of exhausted and disgusted women, Forbes wrote how she was powerless to comfort the boy or confront his abusers. “So we face the other way and look at the Statue of Liberty and tremble,” she wrote.

The New York Daily News was scathing:

“MISS FORBES’ STORIES suggest that some of our government processes are still in the middle ages…The reputation for ferocity is spread over Europe. The immigrant arrives expecting mistreatment… The United States cares as much about the receipt of new citizens as the stockyard cares about the receipt of new cattle.

Genevieve Forbes Herrick was buried in Arlington National cemetery beside her husband, John Herrick, also a former Tribune reporter and writer and later in the federal bureau of Indian affairs.

Mrs. Herrick was a staff member of the Chicago Tribune from 1918 to 1933, part of which time she was on the staff of the Washington bureau. Later she worked as staff writer for Country Gentleman Magazine; press relations chief for the women’s army corps in 1942 and 1943, and headed the book and magazine section of the office of war information from 1943 to 1945. She was a former president of the Women’s National Press club in Washington.

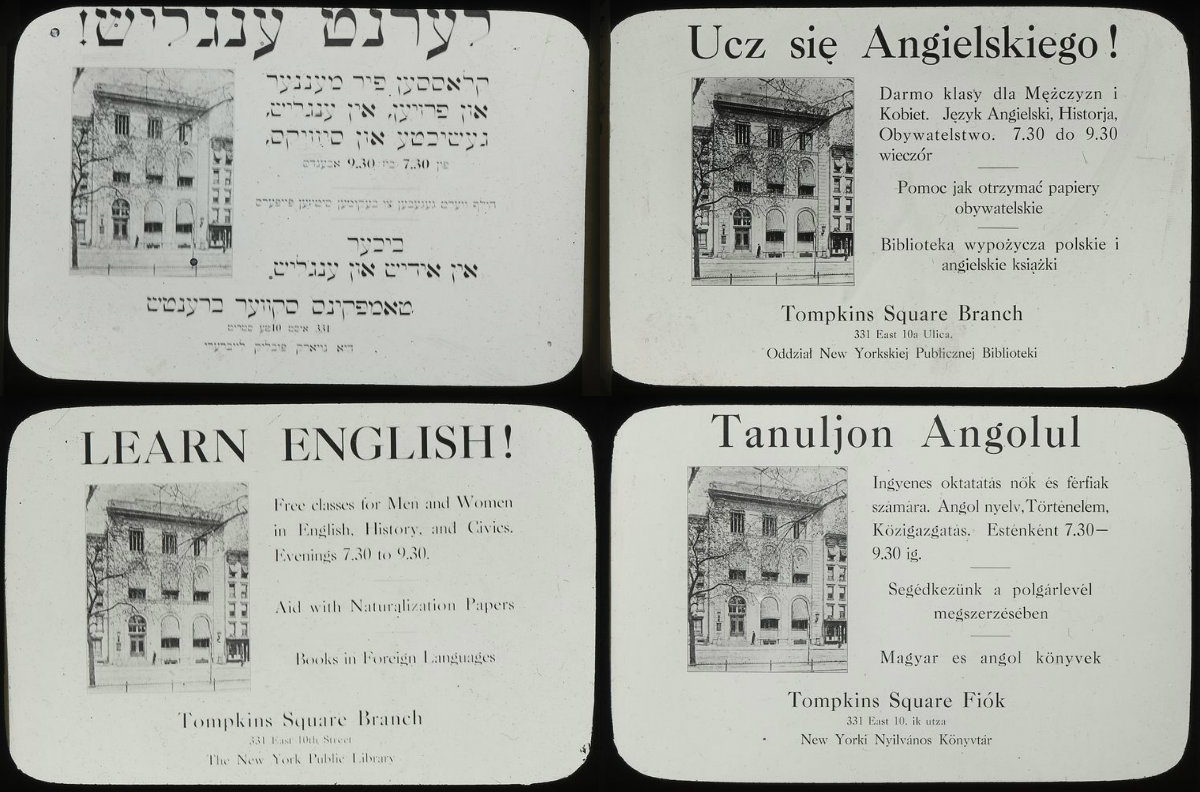

Post-war immigration quickly revived and 560,971 immigrants passed through Ellis Island in 1921. The first Immigration Quota Law passed the U.S. Congress, adding to the administration problems at Ellis Island. It provided that the number of any European nationality entering in a given year could not exceed three percent of foreign-born persons of that nationality who lived in the U.S. in 1910. Nationality was to be determined by country of birth, and no more than 20 percent of the annual quota of any nationality could be received in any given month. The total number of immigrants admissible under the system was set at nearly 358,000, but numerous classes were exempt.

The Immigration Act of 1924 further restricted immigration, changing the quota basis from the census of 1910 to that of 1890, and reducing the annual quota to some 164,000. This marked the end of mass immigration to America. The Immigration Act also provided for the examination and qualification of immigrants at U.S. consulates overseas. The main function of Ellis Island changed from that of an immigrant processing station, to a center of the assembly, detention, and deportation of aliens who had entered the U.S. illegally or had violated the terms of admittance.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.