“Come to the edge,’ he said. ‘We are afraid,’ they said. ‘Come to the edge, he said,’ and slowly, reluctantly, they came. He pushed them and they flew.”

― Guillaume Appolinaire

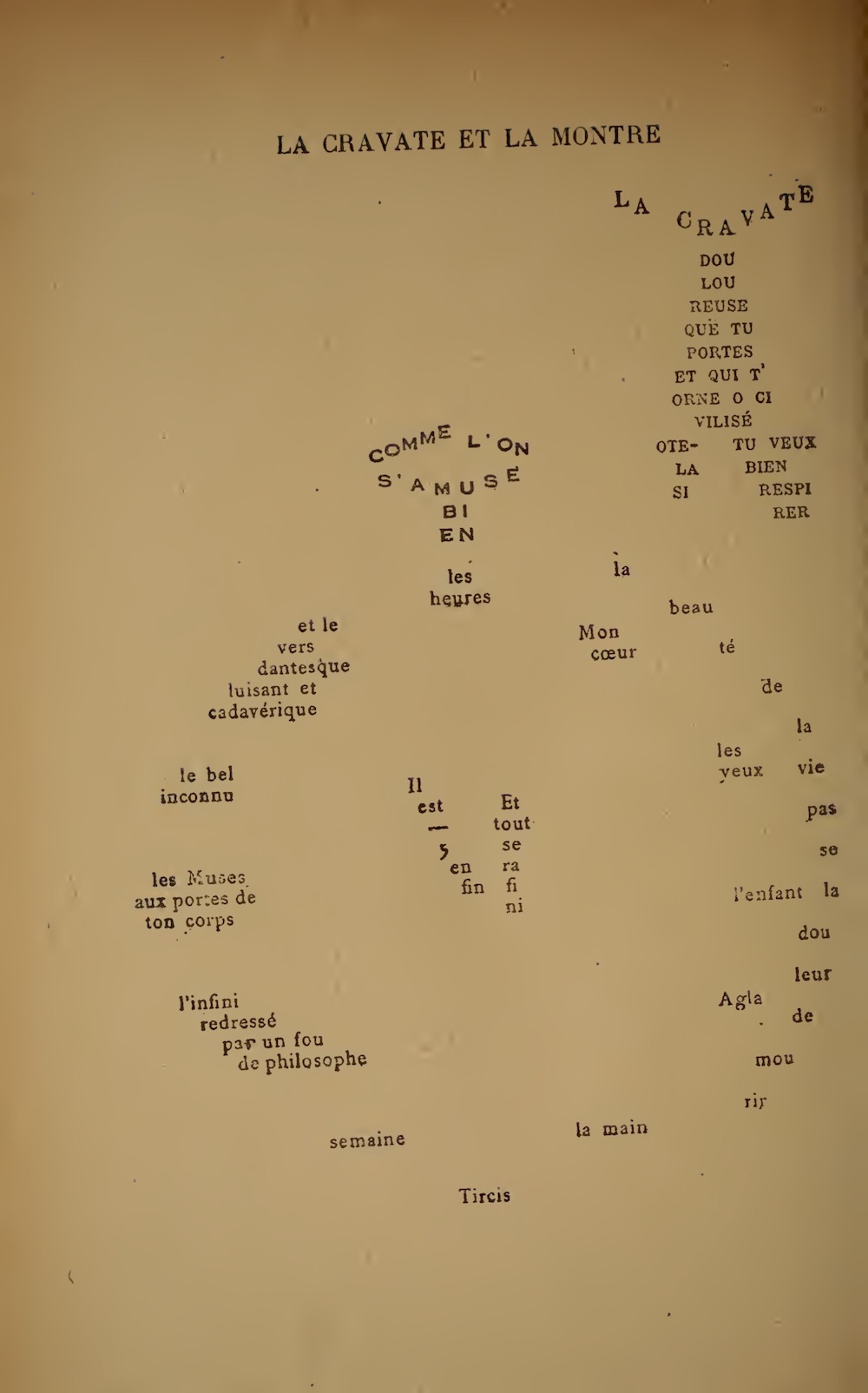

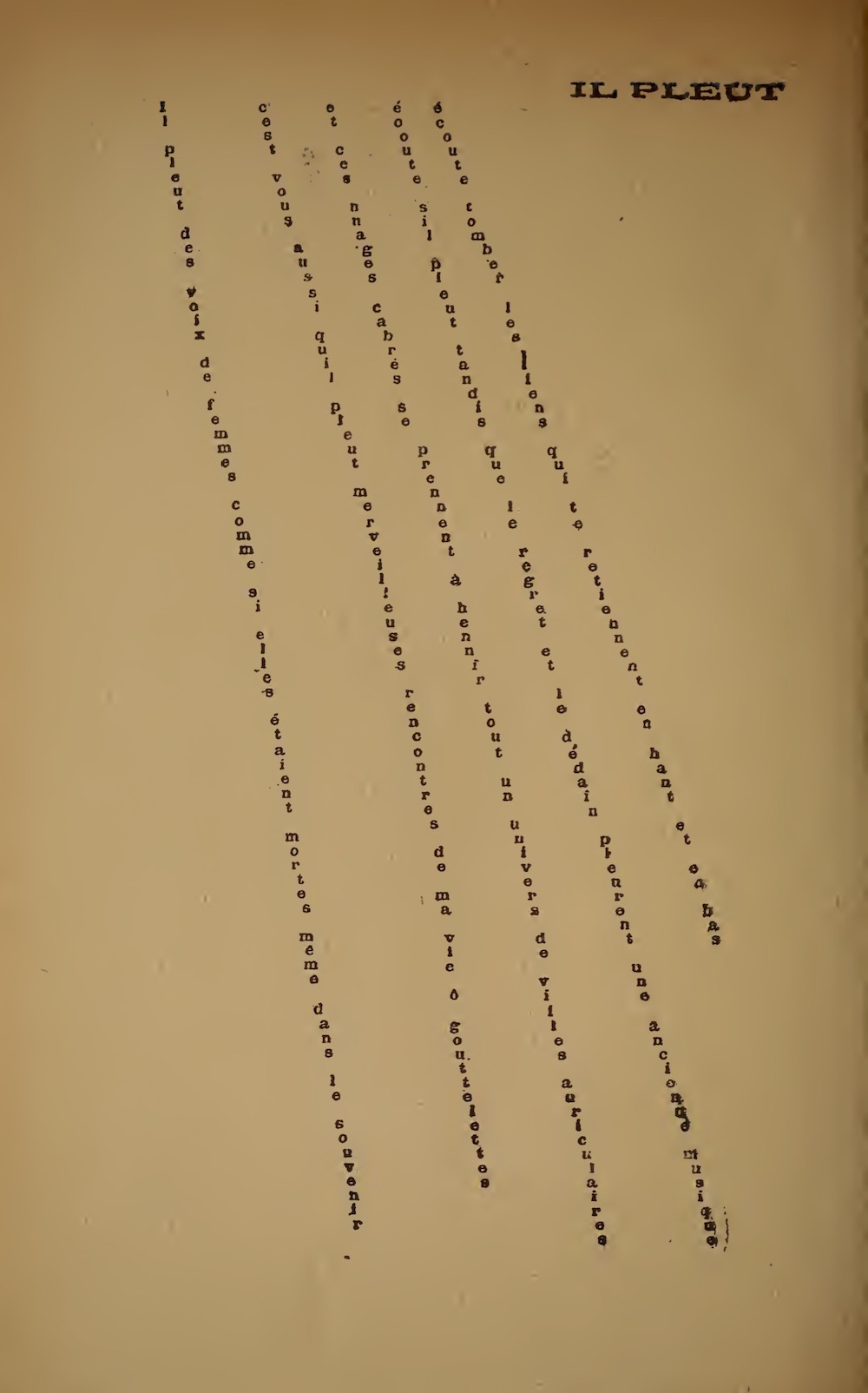

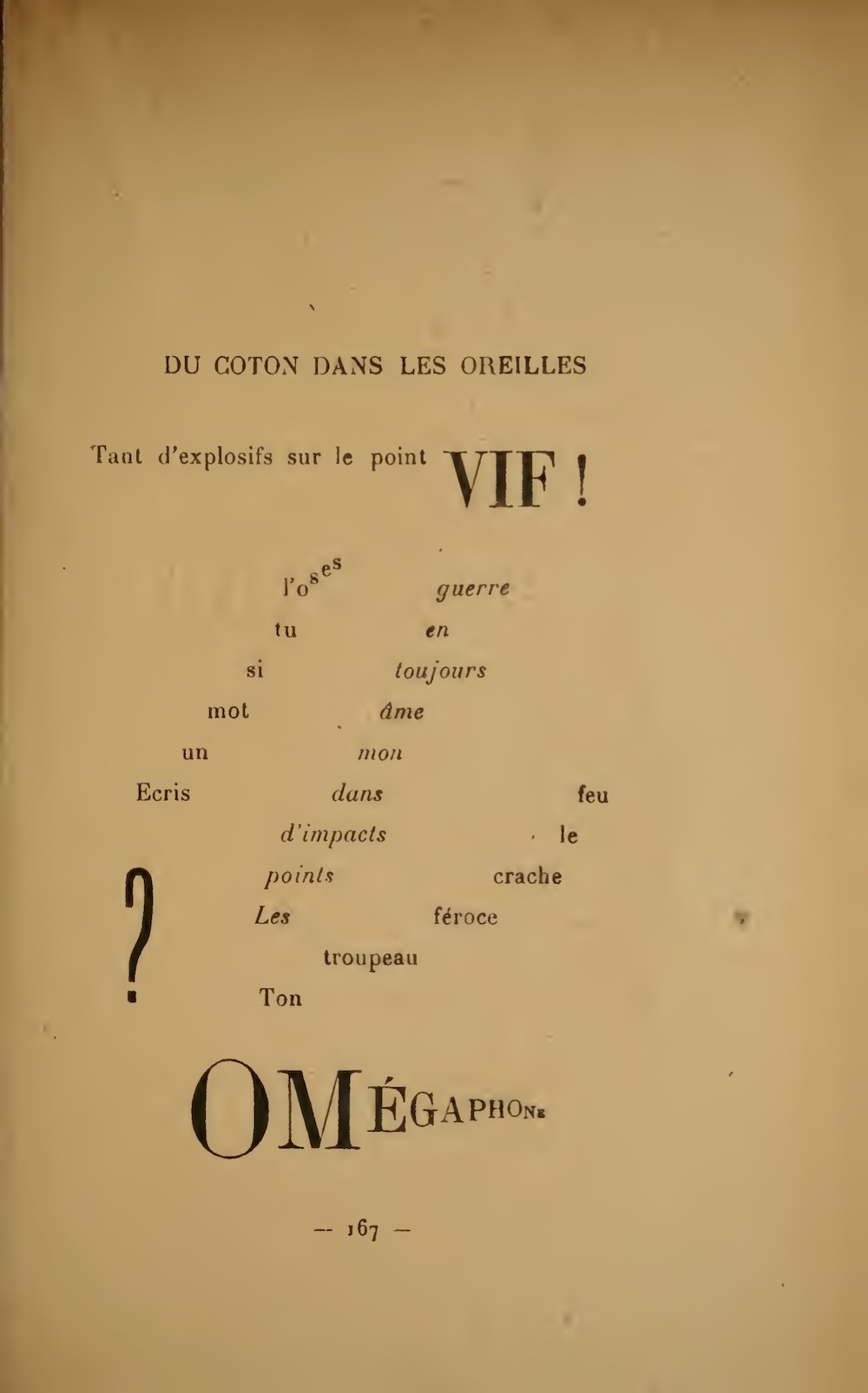

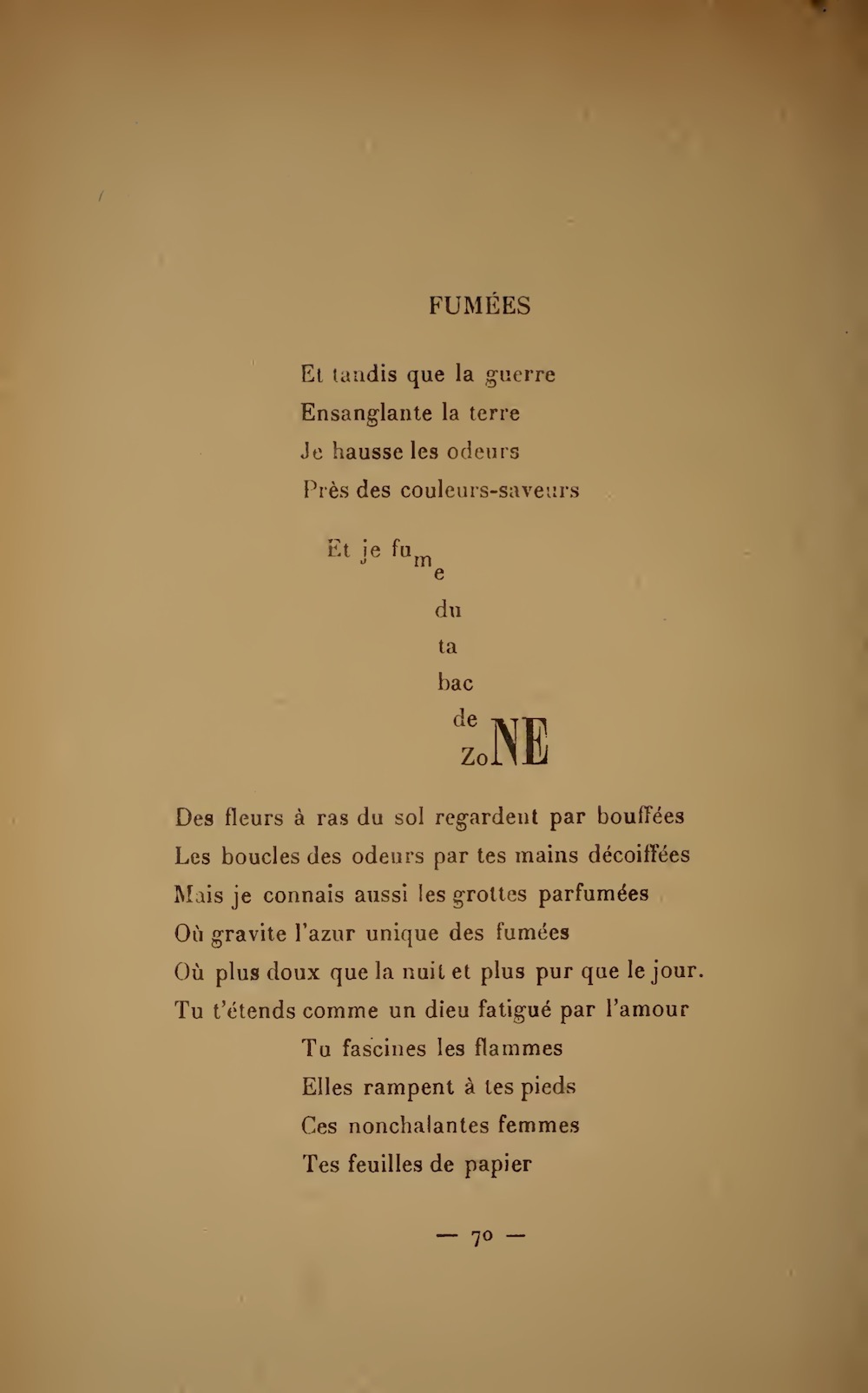

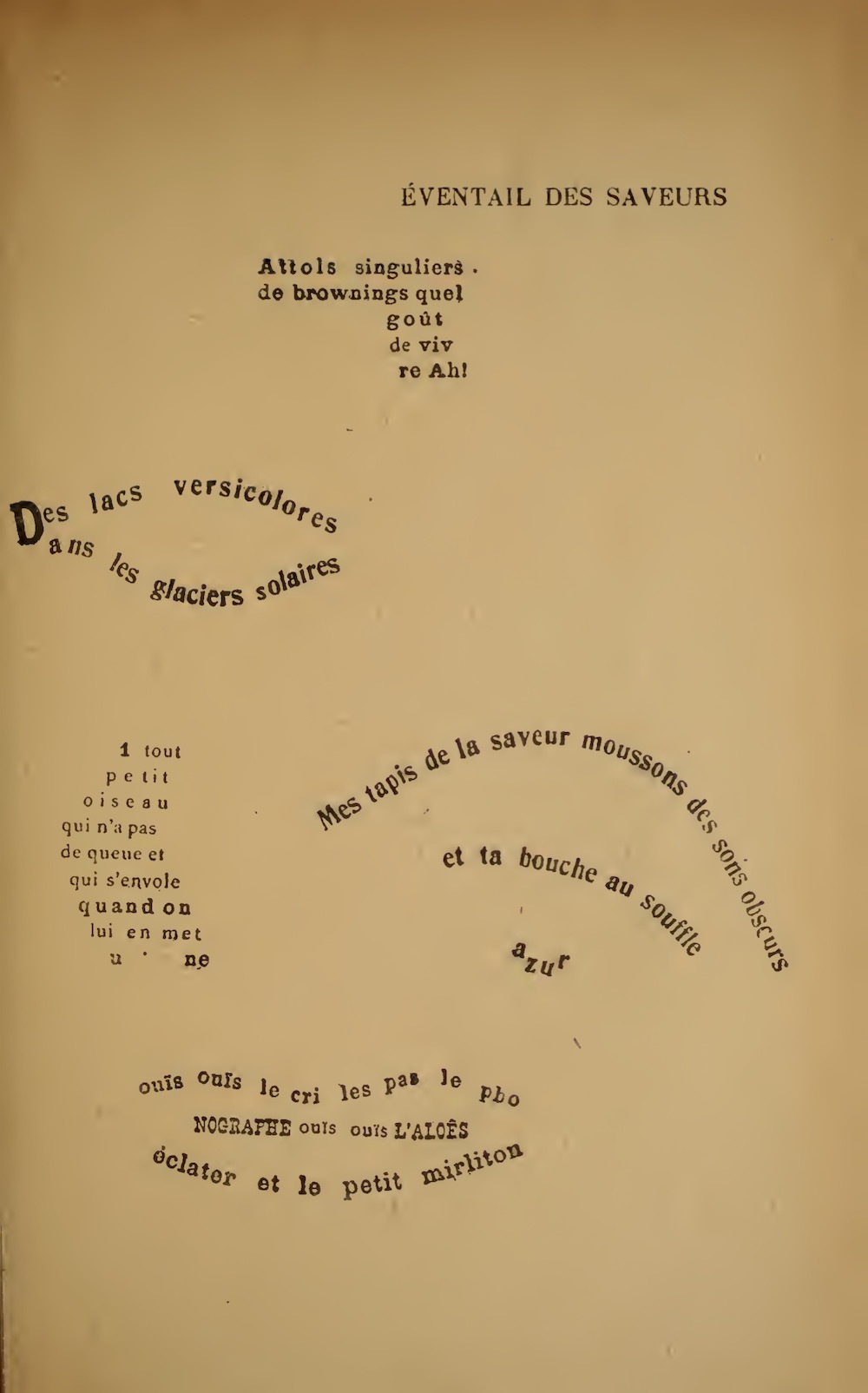

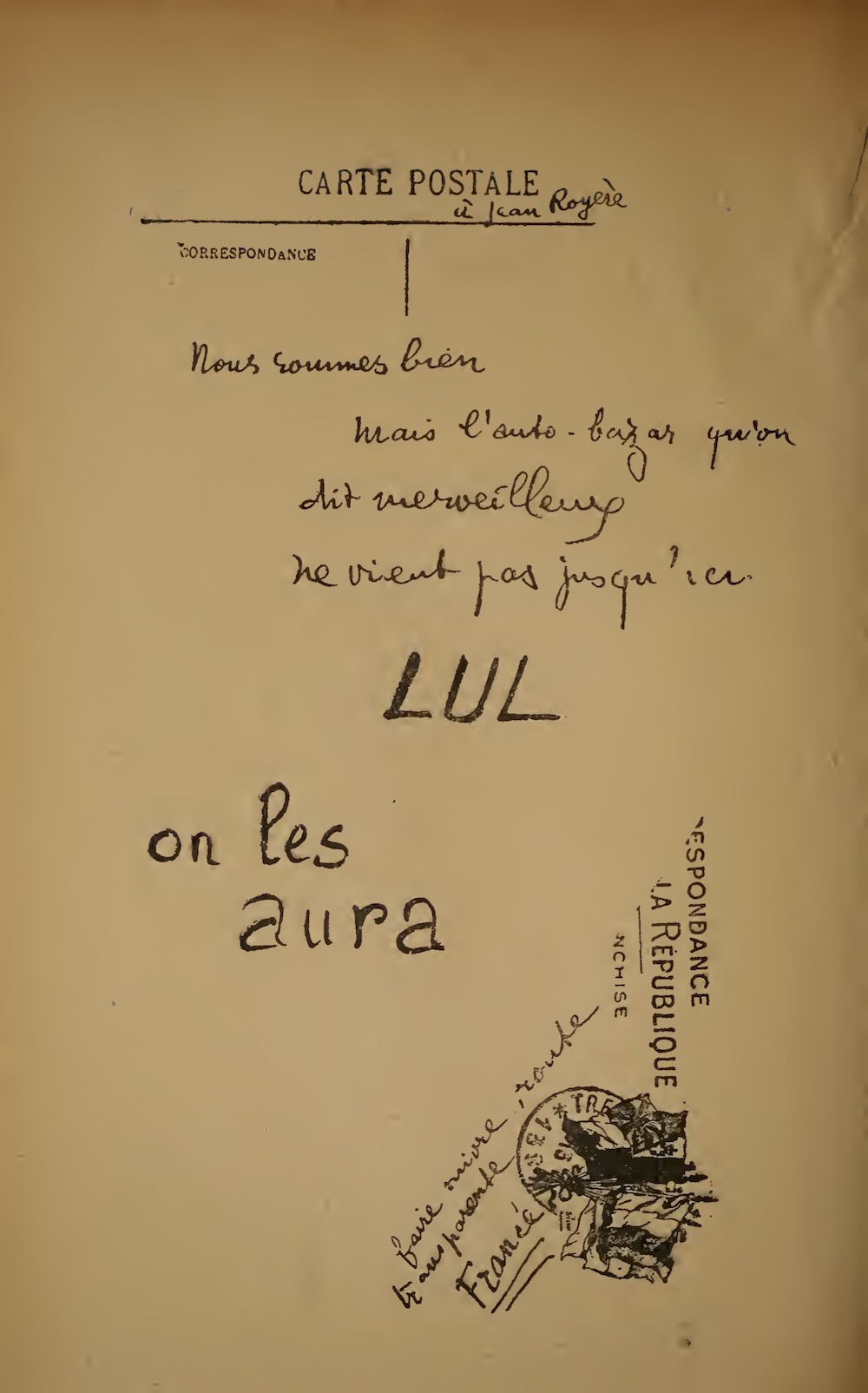

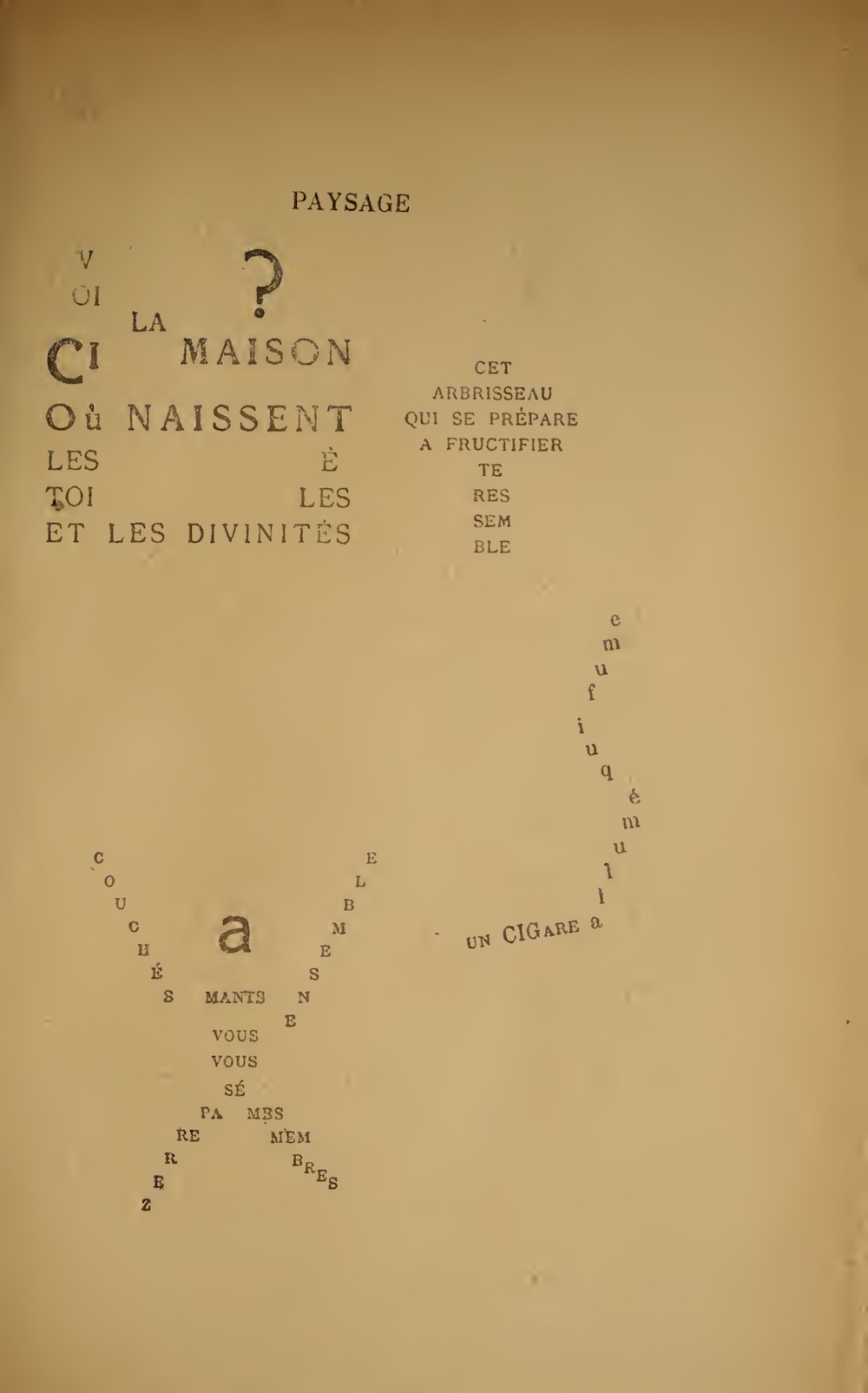

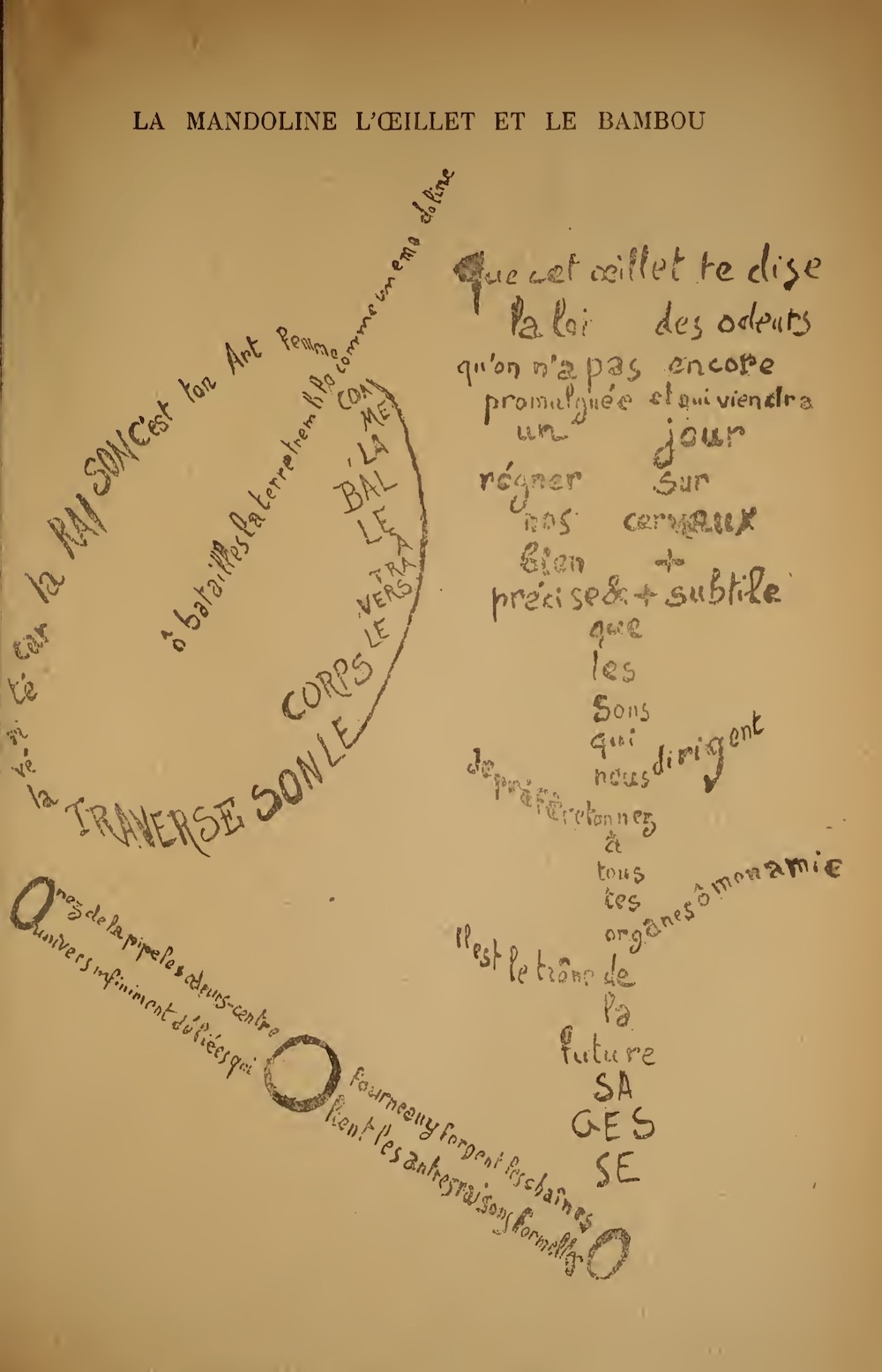

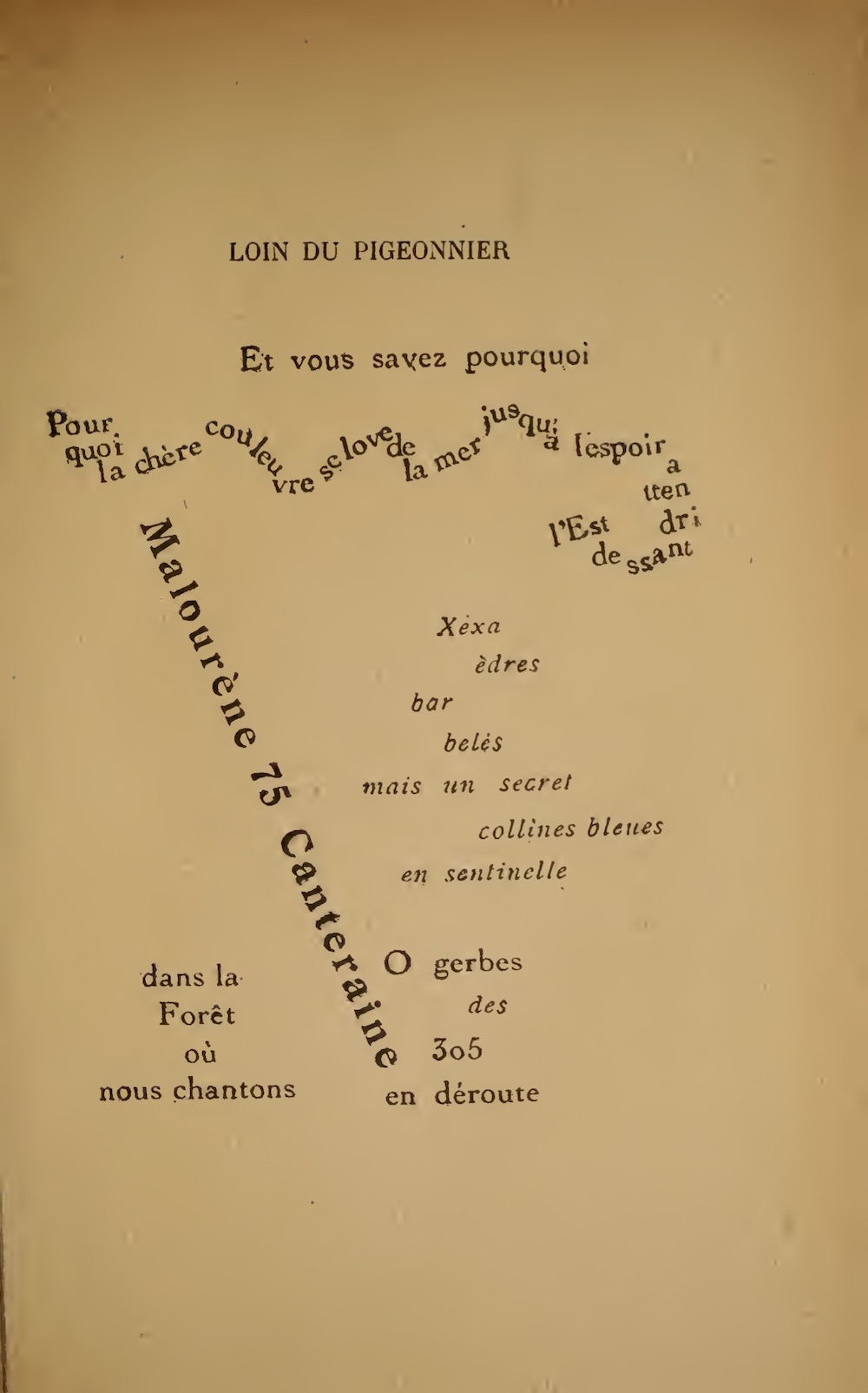

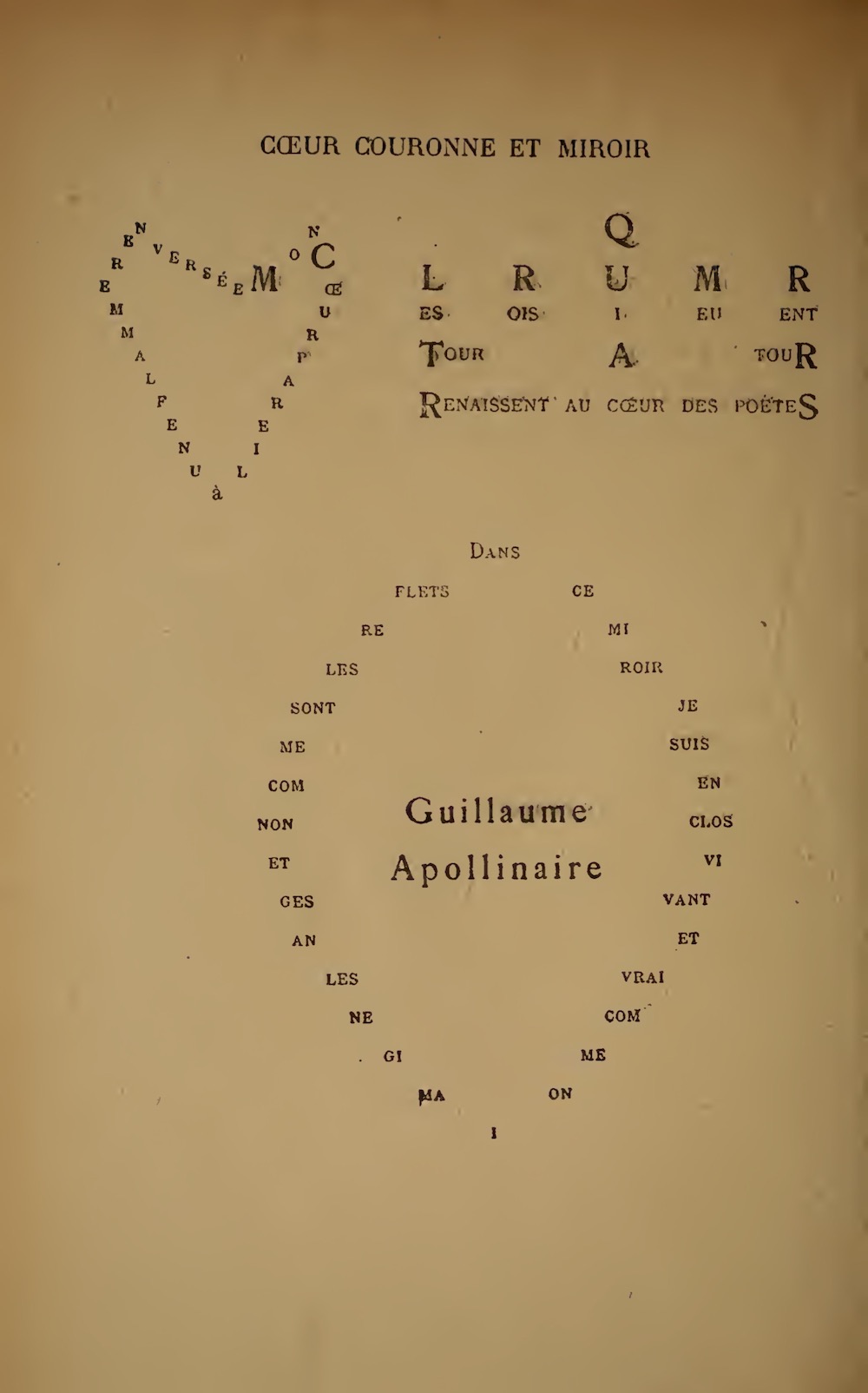

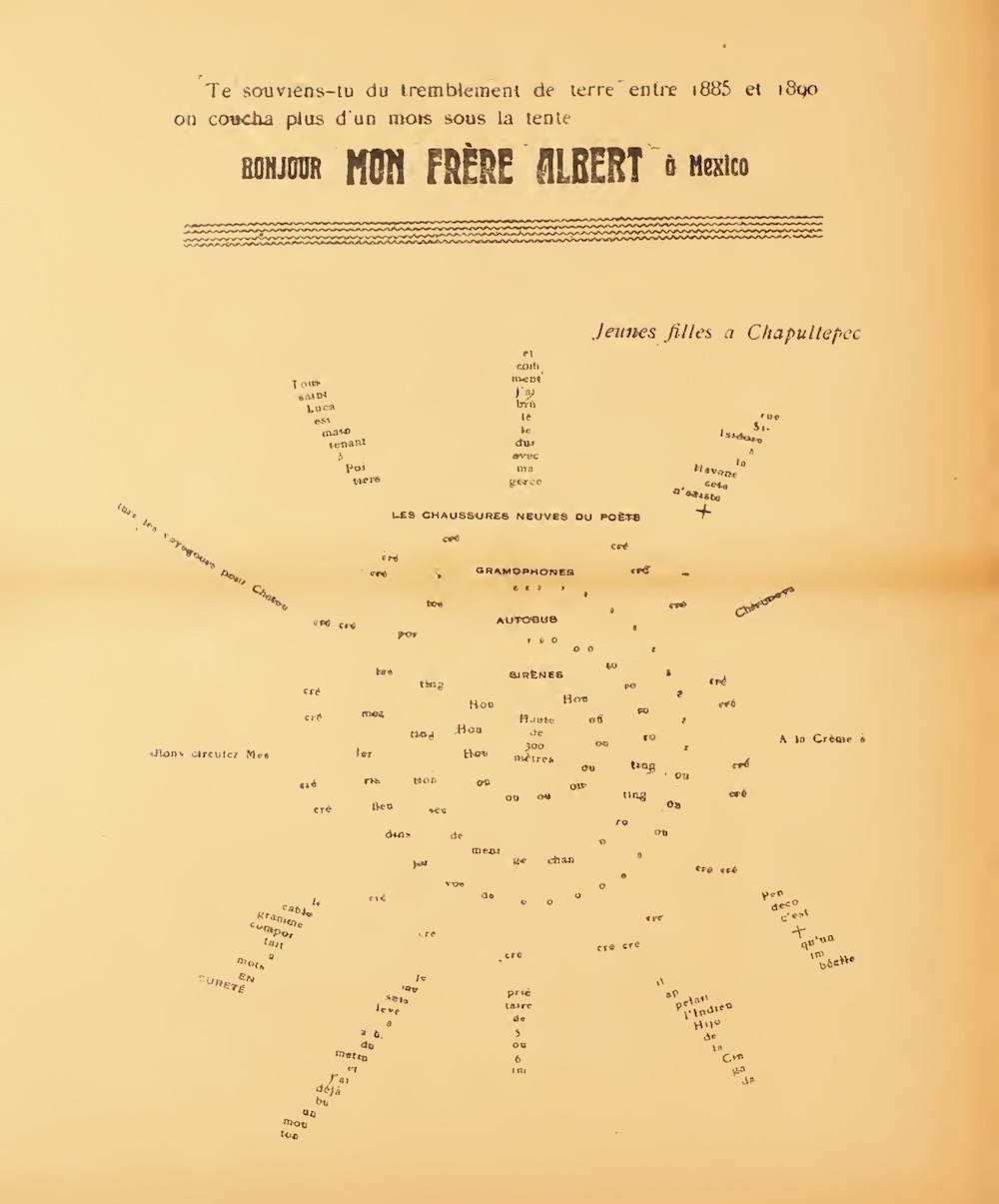

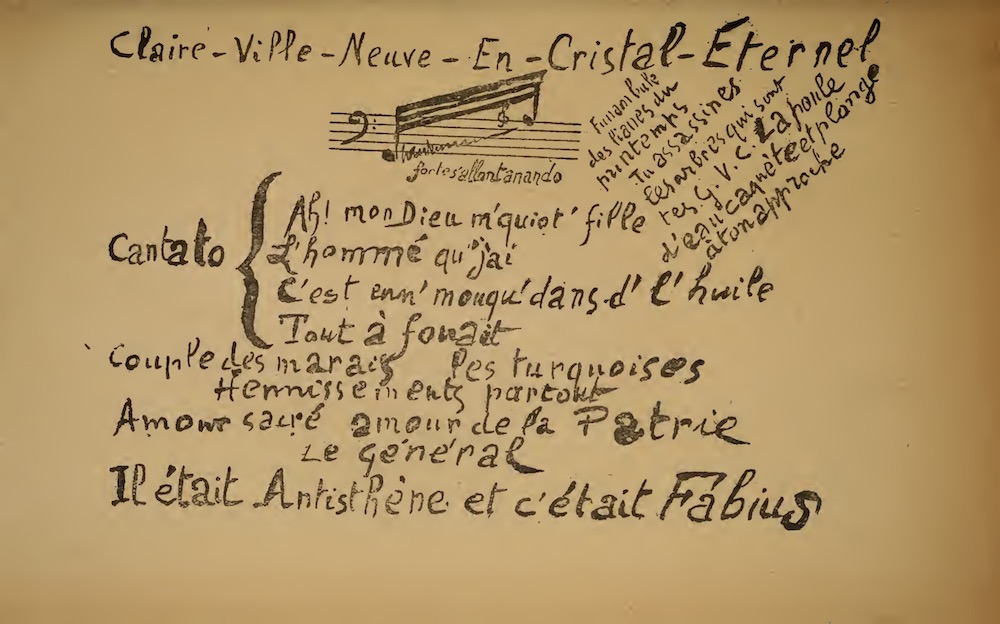

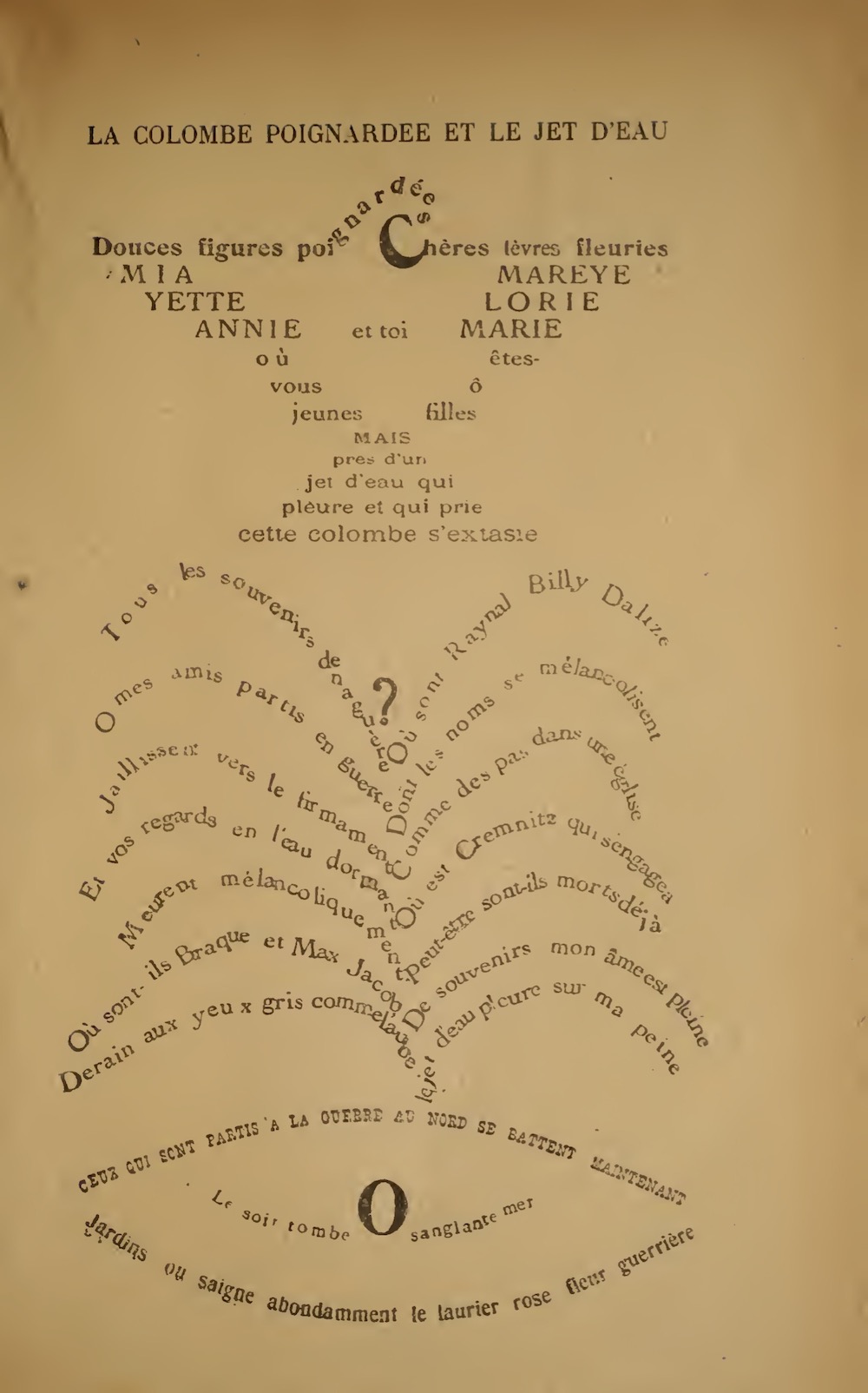

The form is part of the message in French writer Guillaume Apollinaire’s “caligrams”, in which the shape of the words on the page and the font and type create meaning.

Apollinaire wrote erotica, phantasms and proclamations. He was a poet, polemicist, self-publicist, playwright, librettist, artist, traveller, soldier and carouser. A central figure of various artistic -isms that were thriving in Paris in the early 20th Century, he became the living spirit of the city’s avant-garde on the eve of the Great War.

And owing to his charm and desire to communicate with everyone and not simply the elite and knowing, as is the way with so much art and literature they label ‘important’, his legacy is perhaps best illustrated through his experimental, highly stylistic and accessible caligrams.

Apollinaire explains:

The Calligrammes are an idealisation of free verse poetry and typographical precision in an era when typography is reaching a brilliant end to its career, at the dawn of the new means of reproduction that are the cinema and the phonograph. (Guillaume Apollinaire, in a letter to André Billy)

Many of his designs appear in Calligrammes; poèmes de la paix et da la guerre, 1913-1916 (Poems of Peace and War 1913-1916), a book published a year after his death.

Il Pleut by Guillaume Appolinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire

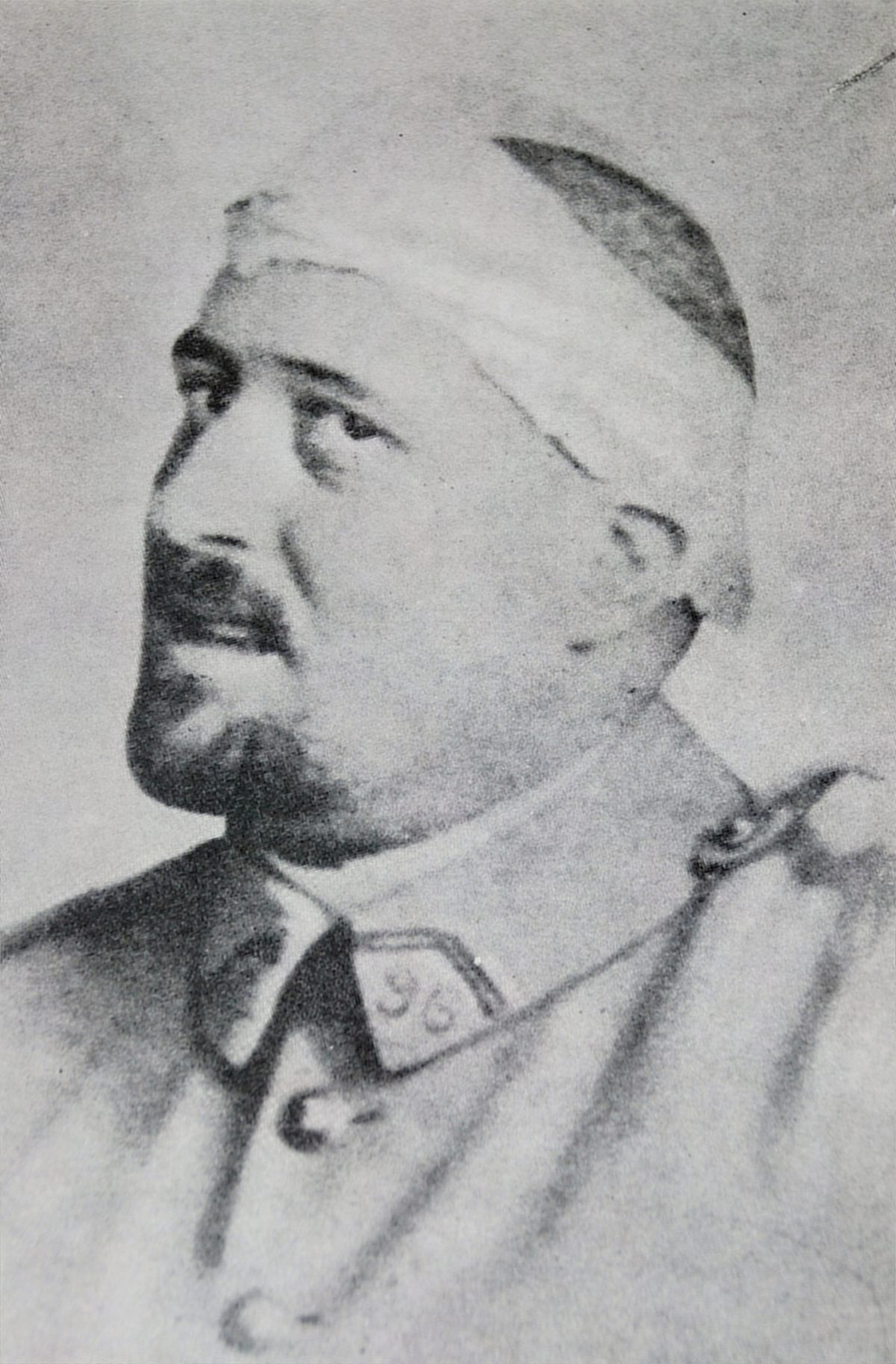

Born in Rome to Polish noblewoman Angélique Alexandrine de Kostrowitzky, who had taken refuge in the papal court, Apollinaire (August 26, 1880 – November 9, 1918) was baptised as Guillaume Albert Wladimir Alexandre Apollinaire de Kostrowitzky. At the time, the identity of this father was unknown – his friend Pablo Picasso would joke that Apollinaire was the son of the Pope himself. His father was decades later identified as one Francesco Flugi d’Aspermont.

After working as a bank clerk in Paris, he became friends with many avant-garde artists, including Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Rousseau and Marcel Duchamp. He became, what one critic called, “an agitator for art, writing with boundless enthusiasm in favour of the works of the coming generation”.

He published fiction and poetry, and edited a number of avant-garde literary journals, in which he championed the work of artists and writers, including Braque, Giorgio de Chirico, Marie Laurencin (with whom he had a love affair), Picasso and Gertrude Stein:

Apollinaire exhorted Henri Matisse, at a time when his work was being condemned as “a pot of paint flung in the public’s face” – “People look at you and see a monster when there is, in fact, a miracle”…

He discovered Henri Rousseau [ …] and was among the first to publicise and celebrate the work, and verve, of Marinetti and his Futurists. He arranged the first ever solo exhibition of the magical Russian folk-painter Marc Chagall. His first books of verse were illustrated with woodcuts by the Fauvists Andre Derain and Raoul Dufy. He acted as a mentor to Blaise Cendrars and Marcel Duchamp…

And there was his erotic fiction: The Cheap Little Hole, The 11,000 Rods or The Amorous Adventures of Prince Mony Vibescu, Memoirs of a Young Rakehell and The Debauched Hospodar (sample: “as soon as she had let go of his balls the prince hurled himself upon her”). In Les exploits d’un jeune Don Juan (The Exploits of a Young Don Juan, 1911), a 15-year-old impregnates three women, one of them his own aunt.

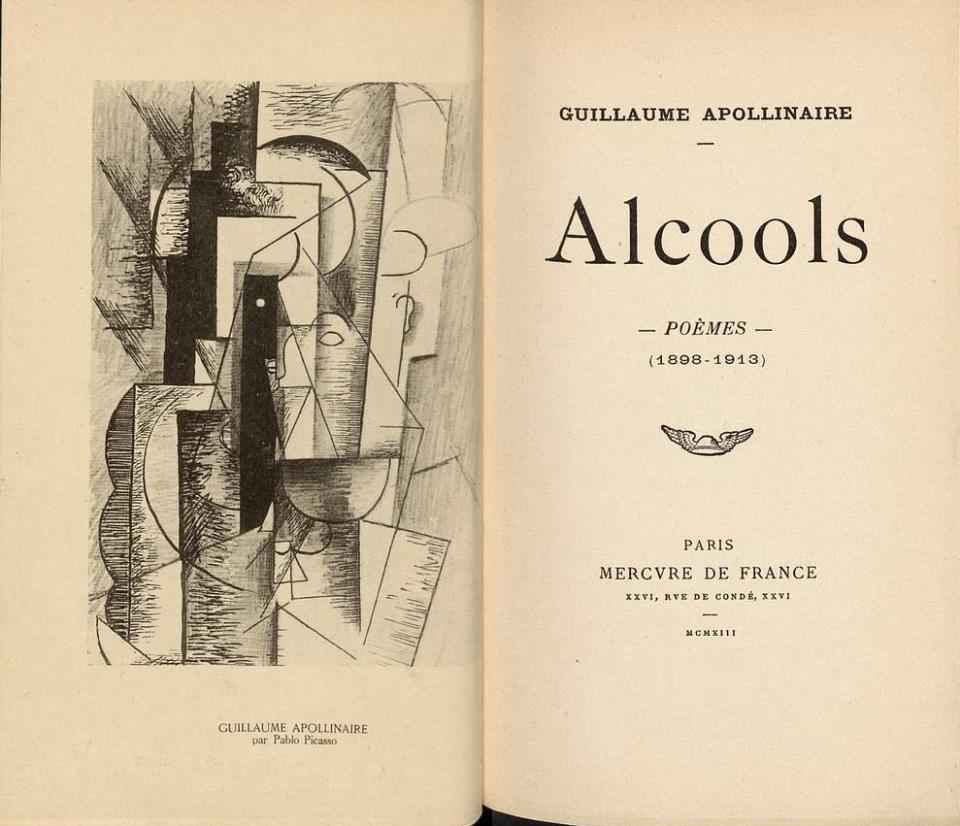

In 1913 the writer published the punctuation-free book Alcools, his first major collection of poetry, with Picasso’s Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire reproduced as a frontispiece.

(An avid advocate of the young Picasso in Paris, Apollinaire received dozens of the artist’s works as gifts.)

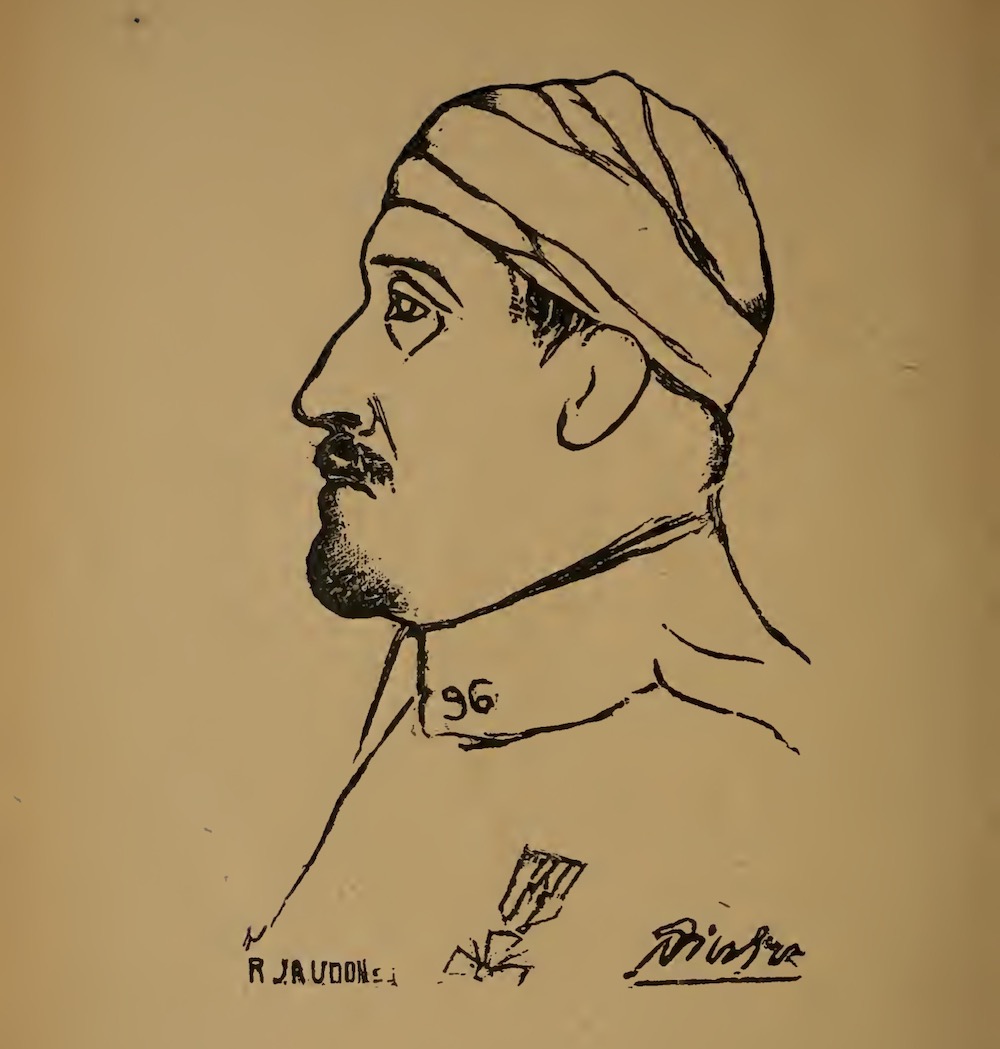

In 1914, he joined the military and fought for France in World War 1. His war ended in 1916 when shrapnel wounded his temple.

It was during his recovery that he coined the term “sur-realism” in the programme notes for Jean Cocteau’s and Erik Satie’s ballet Parade.

He also coined the term “cubism” in his preface to the catalogue for the 8th salon of the cercle d’art, Les Indépendants in Brussels in 1911, and was one of the first critics to define the foundations of Cubism in his essay Les peintres cubistes (The Cubist Painters, 1913).

In 1917 he delivered the lecture “L’esprit nouveau et les poetes”, a manifesto for art in which he called for total invention and full surrender to inspiration.

Shortly before Apollinaire died of Spanish flu in 1918, author Jacques Vache wrote to Andre Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement: “[Apollinaire] marks an epoch. The beautiful things we can do now!”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.