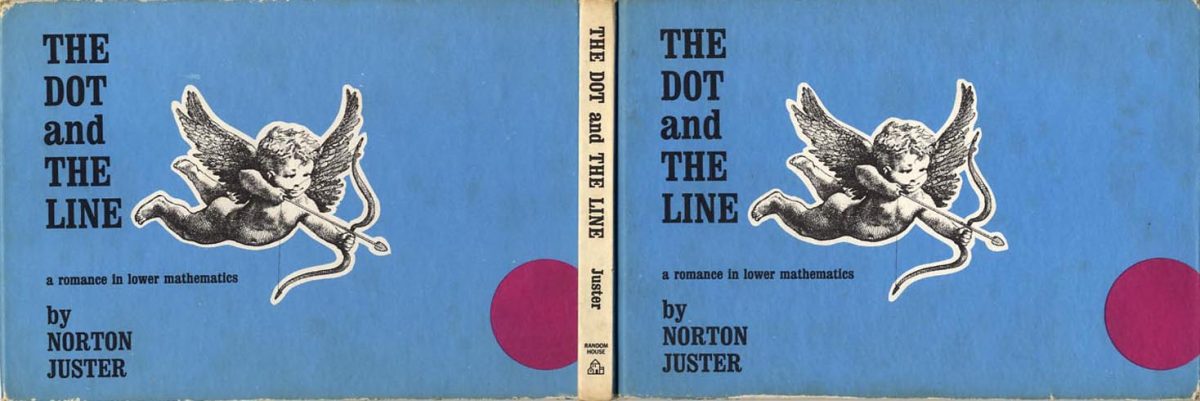

In 1963, Norton Juster (June 2, 1929 – March 8, 2021) wrote and illustrated The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics. To give you an idea of the book’s tone, Juster described himself as “a dedicated mathematician whose efforts have been focused primarily on the verification of supermarket register receipts and the calculation of restaurant gratuities in a number of foreign currencies… has also done pioneering work on the psychological effects of mathematical melancholia.”

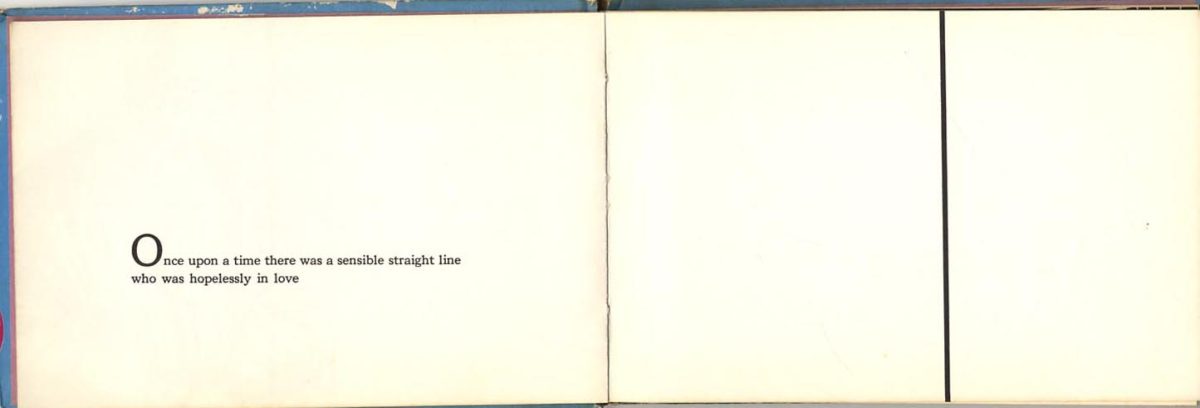

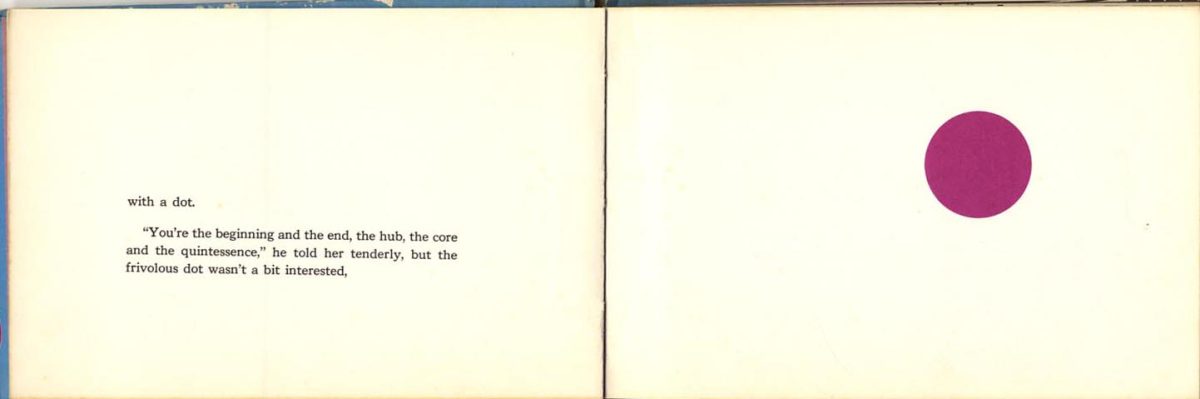

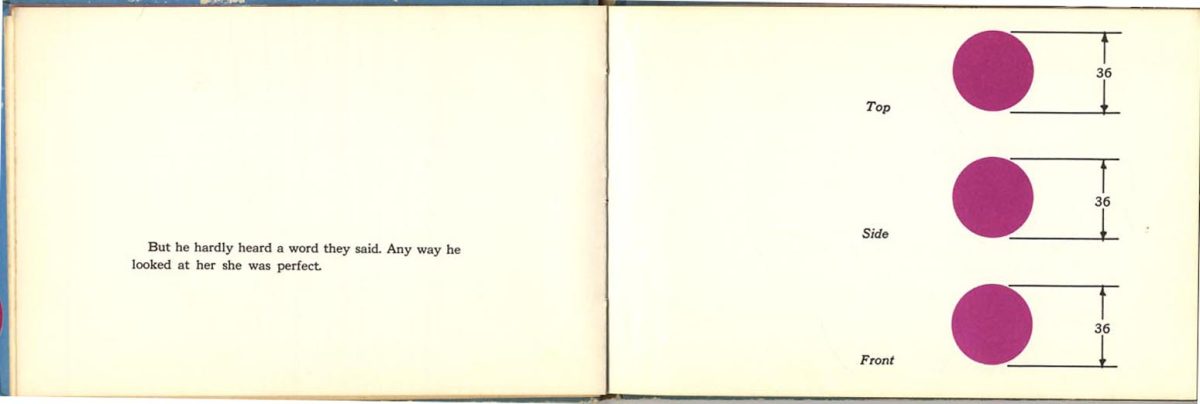

Juster’s wit and love of maths come together in his story of life and romance in Lineland, where women are dots and men are lines. One day, a line falls in love with a dot. But she fancies a squiggle. Undaunted, the line sets out to woo her.

The Dot and the Line was inspired by Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, a satirical novella by the English schoolmaster and theologian Edwin Abbott (20 December 1838 – 12 October 1926). Flatland is a two-dimensional world inhabited by geometric figures – women are line segments; men are polygons. The narrator is a square, a member of the caste of gentlemen and professionals, who guides the readers through some of the implications of life in two dimensions. Life in this two-dimensional universe is governed by rules which are upended in 1999 on the eve of the 3rd Millennium. On New Year’s Eve, the Square dreams of a visit to a one-dimensional world, Lineland, inhabited by men, who are lines, while the women are “lustrous points”.

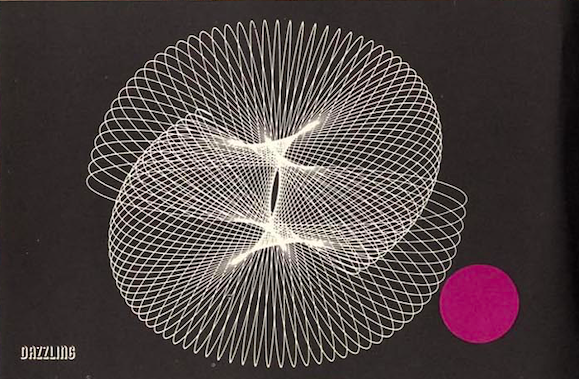

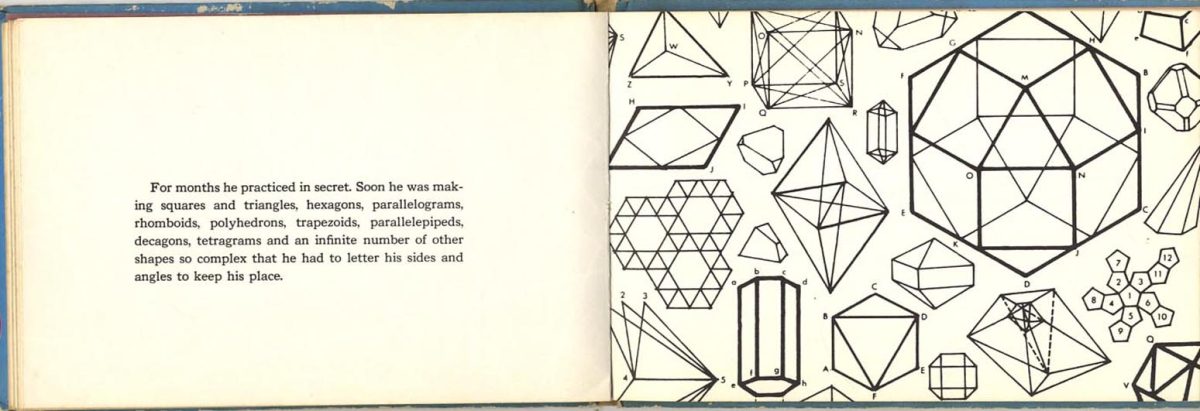

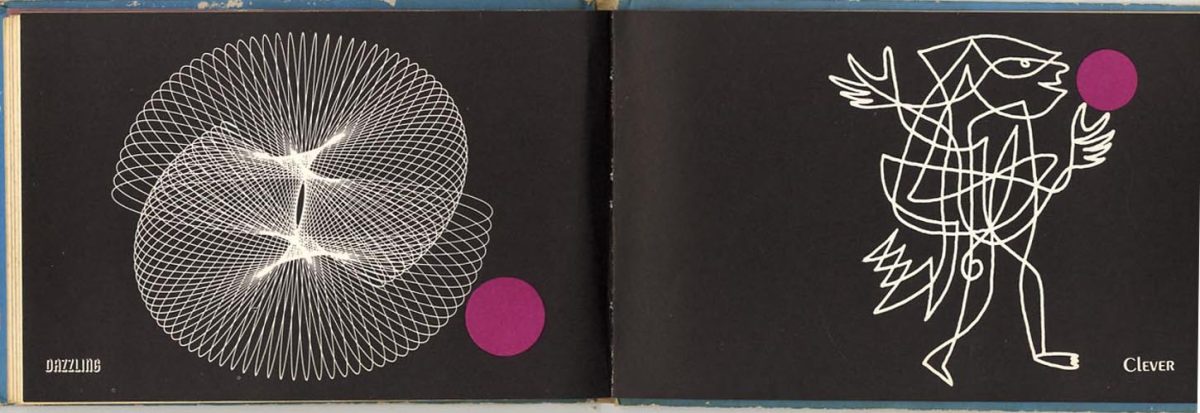

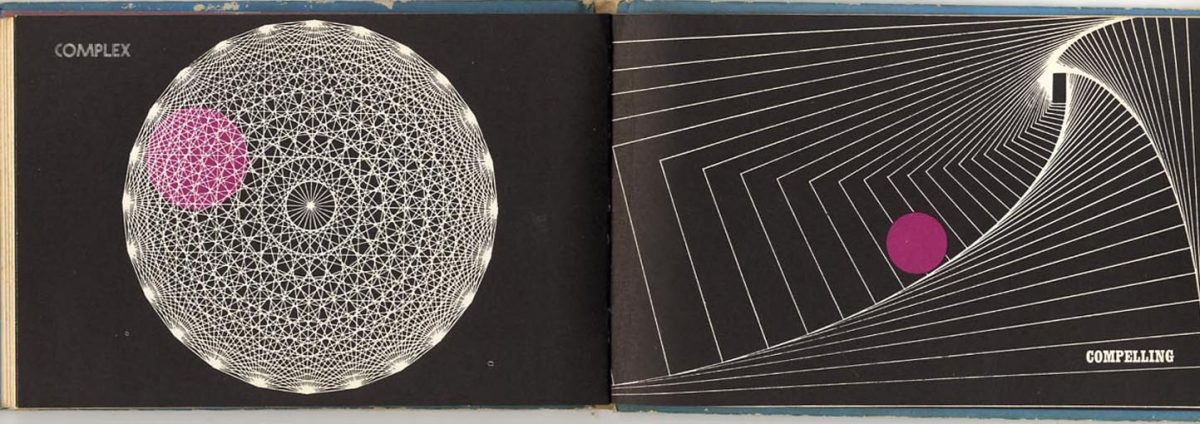

So to Juster’s story of the line who works hard to woo the dot by learning how to turn himself into shapes. He practices in secret and is soon mutating himself into “squares and triangles, hexagons, parallelograms, rhomboids, polyhedrons, trapezoids, parallelepipeds, decagons, tetragrams” and shapes so complex that he can’t find a name for them and uses labels to remember how he got there. And then come the magic: he can bend into curves and circles. What shape can he do? “You name it, I’ll play it,” says the line.

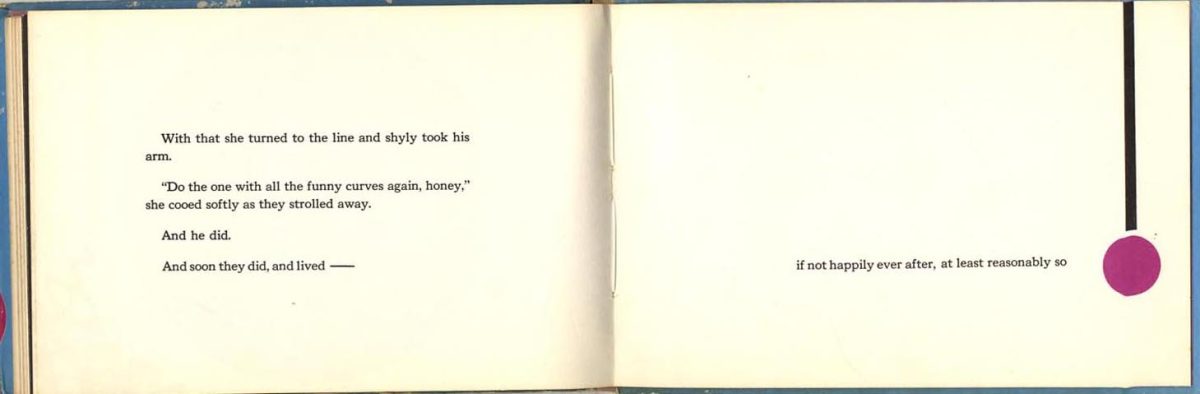

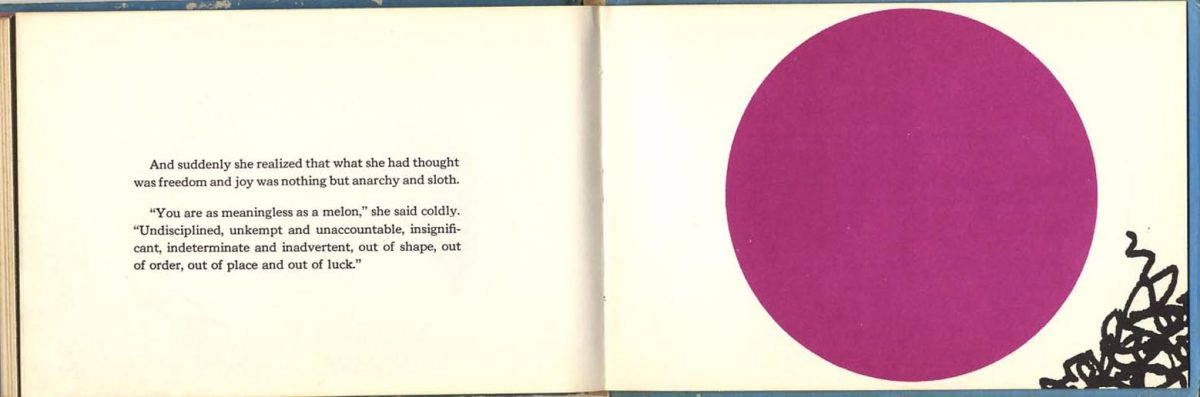

Having mastered the shapes, one night he takes the dot out and explodes into a cosmos of shapes. The dot want to know if the squiggle can also change. Not a bit of it. He’s just a mess. And the dot and line move on together to live “reasonably” happy ever after. The book ends with a moral: “To the vector belongs the spoils.”

In 1965, The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics was adapted into the Oscar-winning short film directed by Chuck Jones and Maurice Noble and narrated by Robert Morley.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.