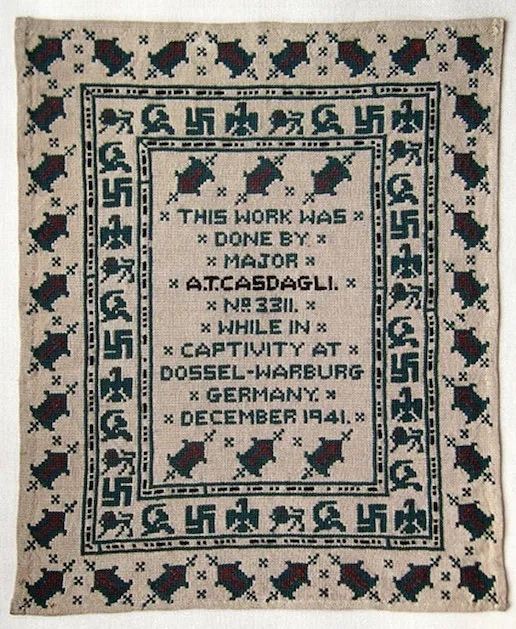

At the prisoner of war camp in Spangenberg castle, Germany, Major Alexis Casdagli began to stitch. Using a piece of canvas handed to him by a fellow inmate, thread from an old jumper and a hidden needle, Casdagli created a border of dots and dashes around a frame of swastikas and other emblems. In the centre he stitched the words: “This work was done by Major A. J. Casdagli no. 3311 while in captivity at Dossel-Warburg Germany December 1941.” The Nazis liked the sampler enough to display the artwork at four German camps Casdagli was imprisoned at. But the guards failed to spot the other message told in Morse Code through those dots and dashes: “God Save the King” and “Fuck Hitler!”.

An anglicised Greek, known as Cas, Alexis Casdagli had studied at the elite Harrow School in London. Not long after joining the war effort, he was captured at the Battle of Crete in May 1941. Having run a textile company in his native Greece, Casdagli understood fabric and saw sewing as a way to escape the pain of prison and maintain his focus.

Years later, his daughter Alexis told the Red Cross: “If more men embroidered, there wouldn’t be so many wars.” She said the hobby kept her father “modest, well-tempered, patient”.

And he stitched more messages. “It is 1,581 days since I saw you last but it will not be long now,” he told his son, Tony, in a letter spelled out in stitched letters. “Do you remember when I fell down the well? Look after Mummy till I get home again.”

In a part-map and part-diagram, Cas created a needlework of “Room 13, Spangenberg castle”. The stitching showed inmates’ cells, lumps of coal, a sign saying “bath every 14 days”, and a menu: “soup, potatoes, wurst, bread, semolina.” At the bottom was a Union flag. As Tony recalled in 2011, National flags were forbidden in the camp, so Casdagli sewed a canvas flap over it with “do not open” written on it in German. “Each week the same officer would open the flap and say, ‘This is illegal,’ and Pa said, ‘You’re showing it, I’m not showing it.'”

When the Second World War ended in 1945, Cas was liberated by the American army. He was 39. The next day, he caught a train to London and went to the War Office. He asked for a job overseas, and after a while become the first British consul in the port of Volos, on the Greek west coast.

Greece was in turmoil. The Greek Civil War ( 1946 to 19490 pitched a Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. Many died. Thinking it no place to raise a family, Cas and his second wife Wendy brought Alexis to the UK in 1950.

There he ran Perspex, a plastics moulding company that made the barrels of Parker pens, roof lights and incubators for premature babies. Outside work, he embroidered every day, for two or three hours, for the rest of his life.

In the book, A Stitch in Time: God Save the King? Fu*k Hitler!, Tony, a war hero, says of his father’s work during this time: “It used to give him pleasure when the Germans were doing their rounds. He would say after the war that the Red Cross saved his life but his embroidery saved his sanity. If you sit down and stitch you can forget about other things, and it’s very calming.”

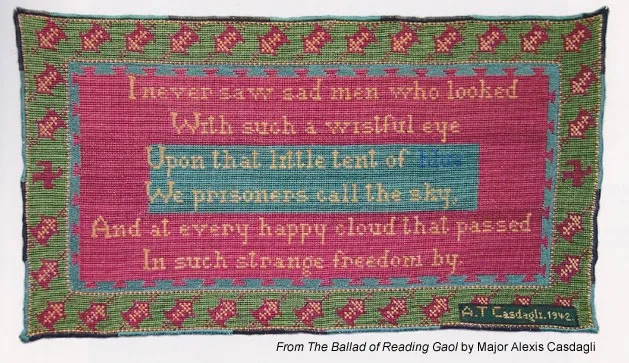

Casdagli wrote a diary during his time in the camps. His diary, called Prouder Than Ever, is insightful, informative, touching and often funny. You can download it for free here. Told by his daughter, the ending is heartfelt:

In 1984, aged 78, Casdagli made another embroidery with a swallowtail. He put a quote in it from Tolstoi’s War and Peace, which he read in captivity between 5th and 9th November, 1944. It was: ‘While there is life there is happiness’. With Wendy’s encouragement, he entered it for a competition and it won him runner-up to the Needlewoman of the Year 1984. He was tickled pink! His prize was a circular sewing box in which he kept his silks, needles and scissors for the rest of his life.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.