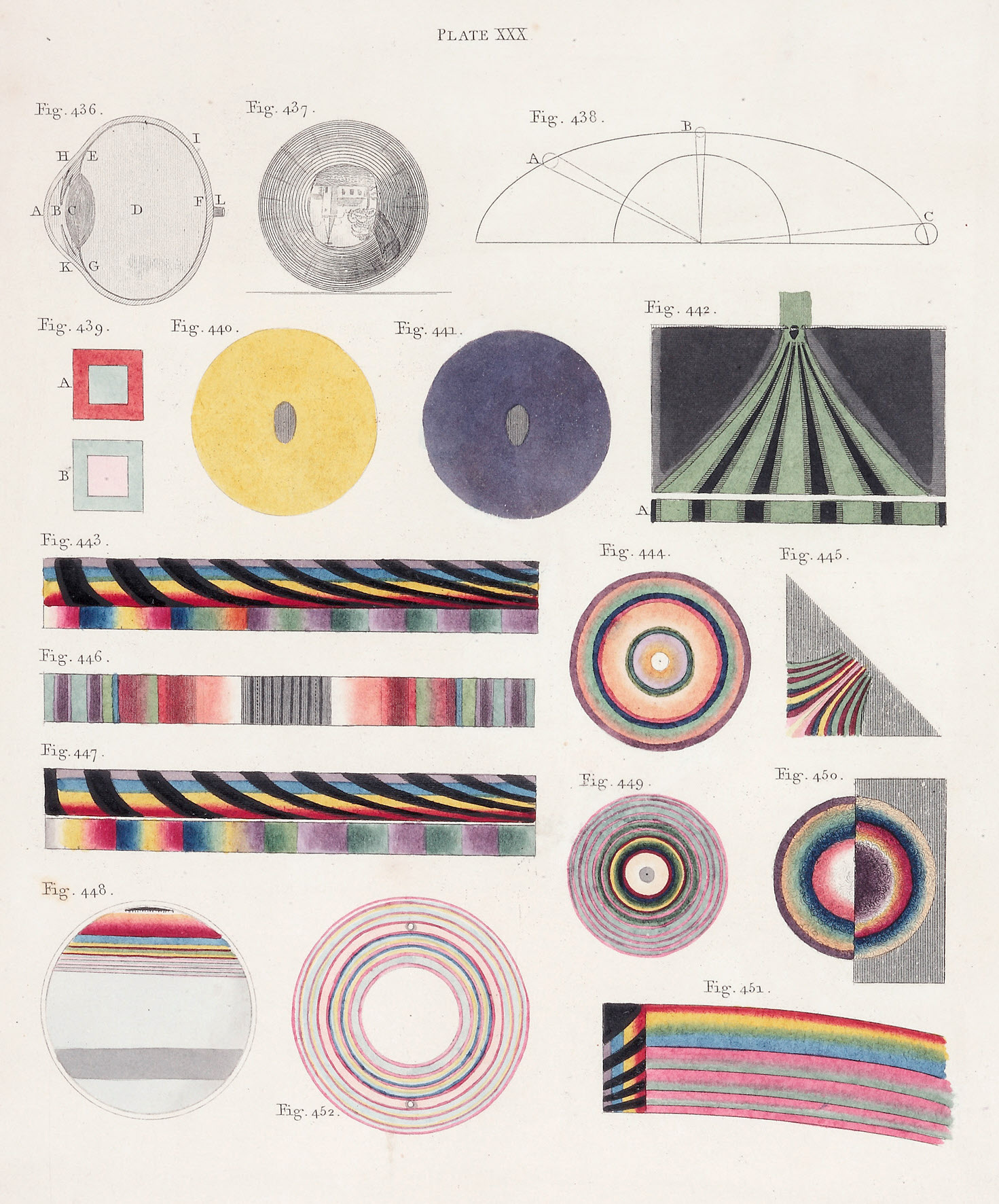

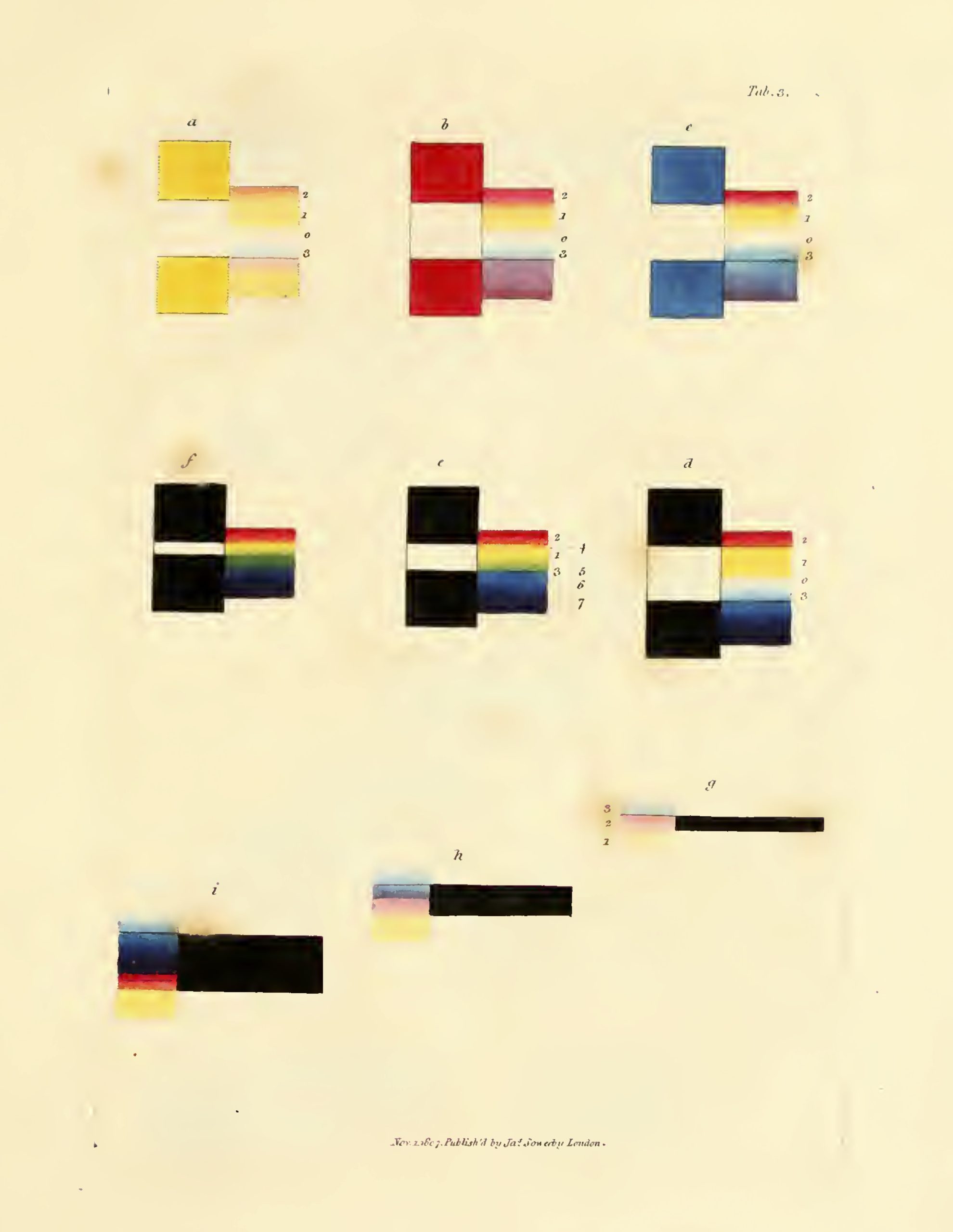

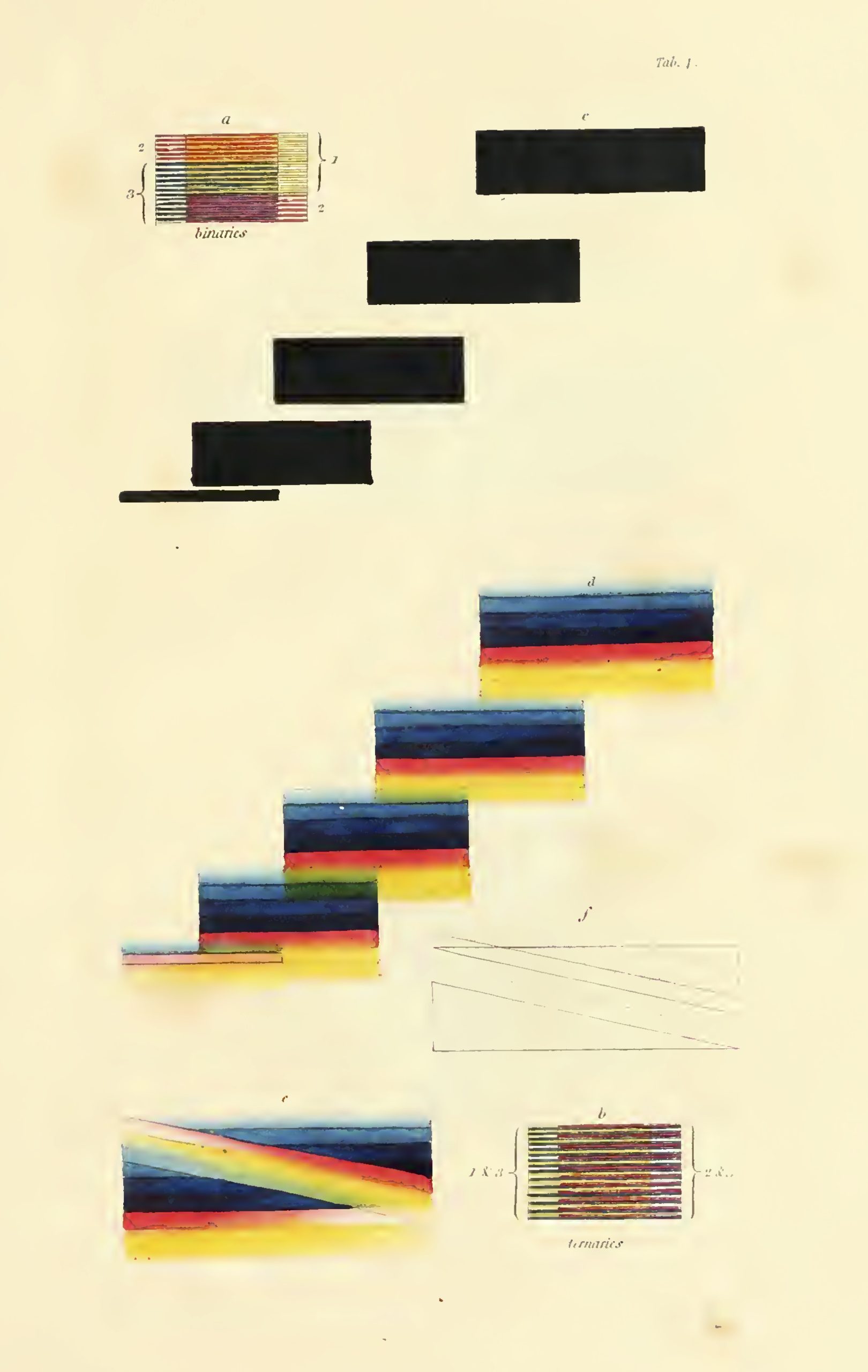

These illustrations are from Theory of Colours: James Sowerby’s ‘A New Elucidation’ (1809). Sowerby (21 March 1757 – 25 October 1822) was an English naturalist and Royal Academy-trained illustrator who specialised in drawing plants and minerals.

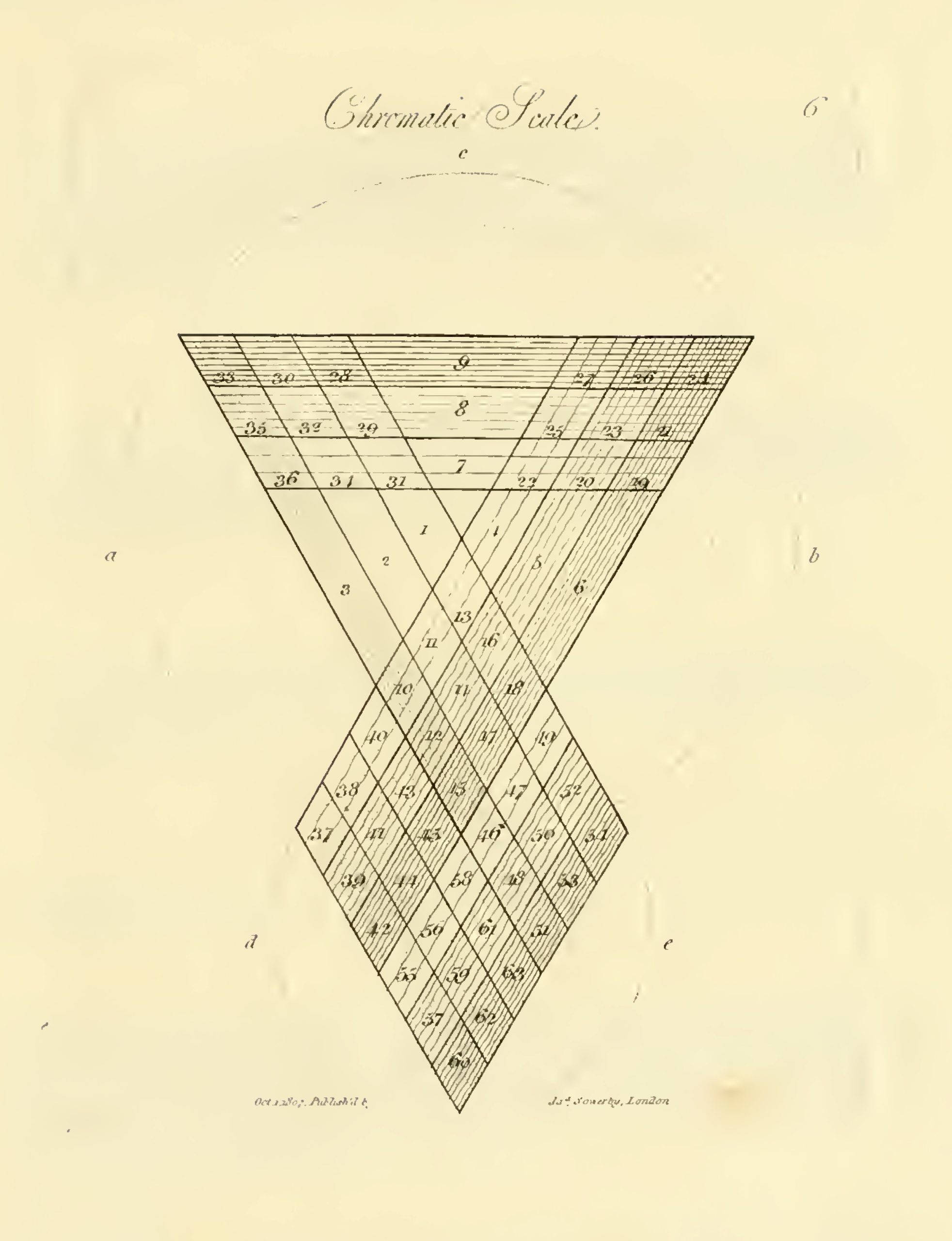

The full title of his illustrated book on colours is ‘A new elucidation of colours, original, prismatic, and material showing their concordance in three primitives, yellow, red, and blue; and the means of producing, measuring, and mixing them. With some observations on the accuracy of Sir Isaac Newton‘.

Sowerby’s colour theory was based on three basic colours: red, yellow and blue.

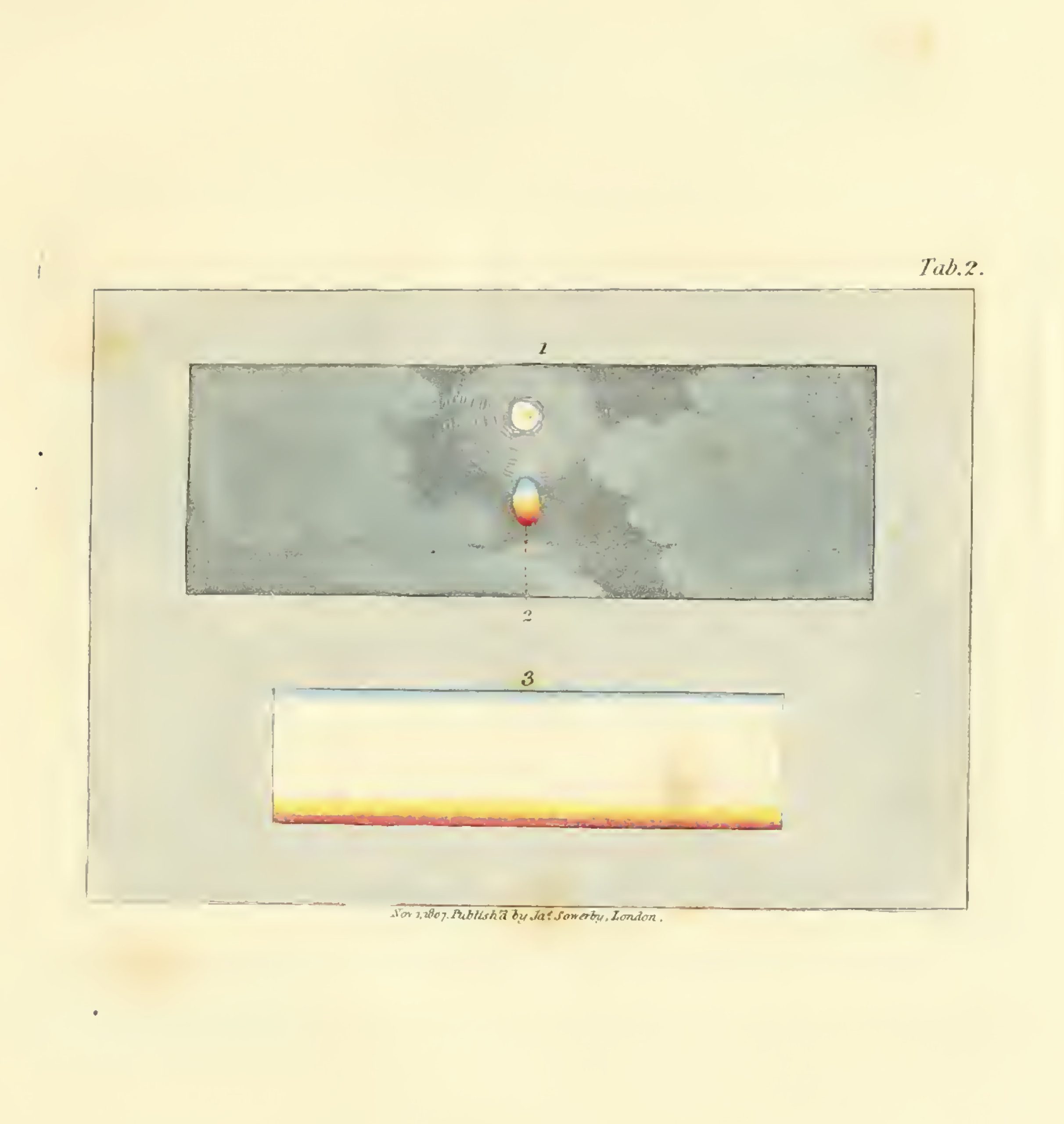

Sowerby’s colour system was published around the time when the English doctor and polymath Thomas Young (13 June 1773 – 10 May 1829) submitted his wave theory of light, stating the eye generates all colours by combining only three wavelengths, red, green and blue. In doing so he overcame the century-old view, as expressed in Newton’s Opticks, that light is a particle. The image below is from Young’s lectures of 1802.

Thomas Young: Plate from “Lectures” of 1802 (RI), pub. 1807

A Universal Language for Sharing Colours

Sowerby was first and foremost an artist. As Joyce Dixon writes:

James Sowerby’s magnum opus was his English Botany (1791–1814), a monumental botanical work comprising 36 volumes and spanning two decades. English Botany offered its readers an encyclopaedic insight into England’s vegetal realm, with each plant specimen meticulously identified, described and depicted in lush, hand-coloured engravings. These full-colour illustrations, vivid and lifelike on the page, are what made English Botany unique and Sowerby famous.

But, as the years passed, Sowerby watched with dismay as the bright hues of his hand-coloured engravings begin to fade and decay – the inevitable action of time and chemical instability working away at his watercolour pigments. Now, the deep red of the petals on Sowerby’s Adonis Autumnis, for example, could not be relied upon as an exact match to the flower itself. In order to overcome the chromatic inaccuracy, Sowerby set out to develop a standard, universal and permanent method of representing natural colour.

So how can you show colours as they really are to someone not there to see them with you?

In her essay about Botanical Histories of Colour Standardization, Elaine Ayers writes:

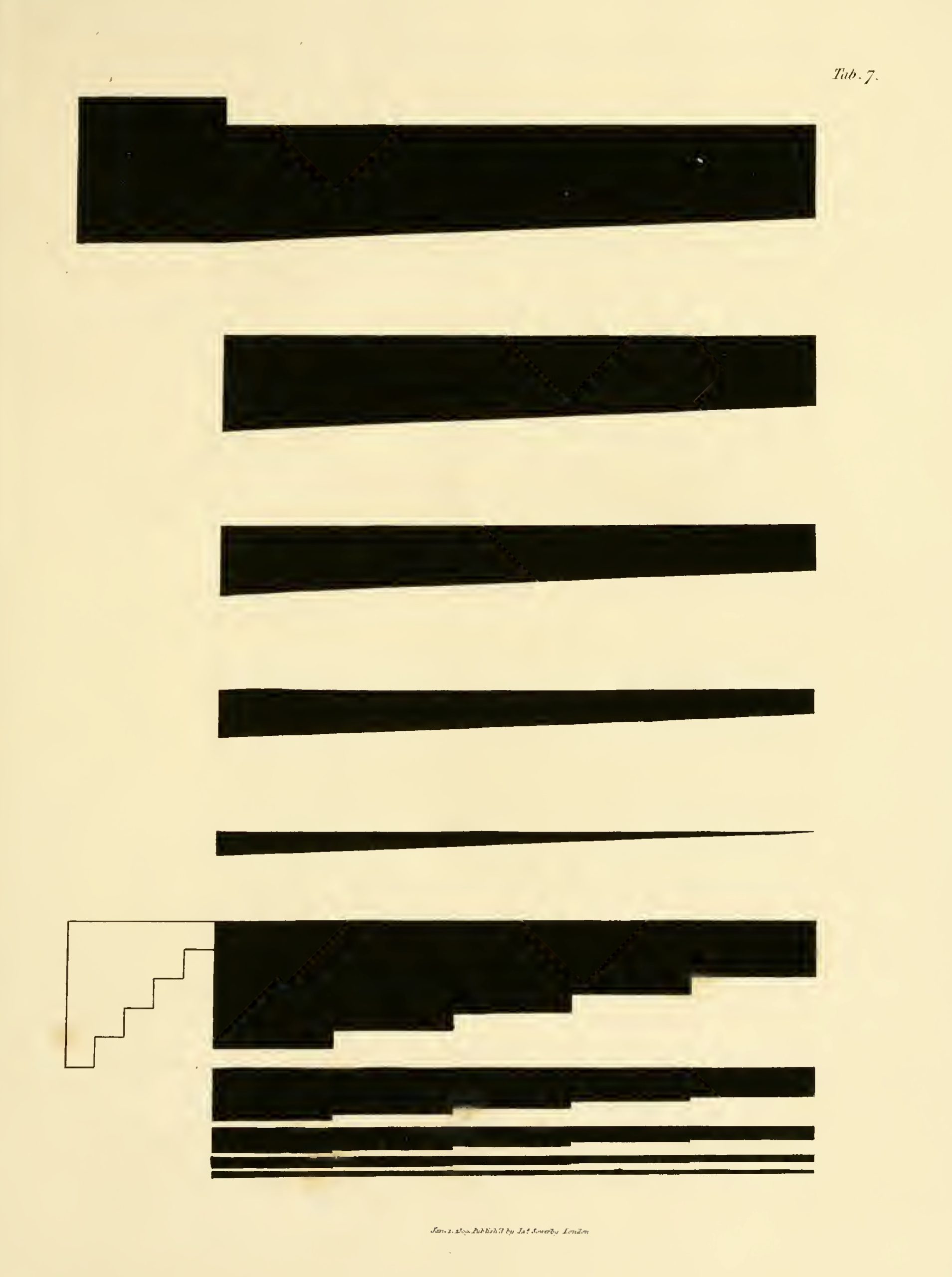

If colour mixing was a physical rather than sensuous phenomenon, as artists like James Sowerby believed, then physical devices modelled on other optometric instruments might help standardize both material colours and viewers’ colour perception. Sowerby, highly trained in the art of botanical illustration, proposed his solution in the early nineteenth century: the “chromatometer,” a strikingly abstract set of black lines and wedges printed on a large sheet of white paper onto which a prism could be refracted, functioning “as an independent instrument (something like a barometer)” for use in the field, study, or herbarium. Working within controlled light and space, botanists and artists could find a specimen or sample’s precise shade on a dissected prism, measure its placement in each segment, and match it to agreed-upon points of pigment reference.

Sowerby intended his device to standardise colours “to all parts of the world, and the remotest ages”, solving the problem of how to represent colours to people not there – especially anyone looking to buy a new orchid or mineral from one of many scientists exploring the world in search of the exotic to sell. But it didn’t work because it was too fiddly and botanists often worked at night.

Soweby’s work features in our study Highlights of Colour Theory: Illustrating The Mysteries of Light In Colour Whels, Tables, Charts And Maps.

Via Data is Nature

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.