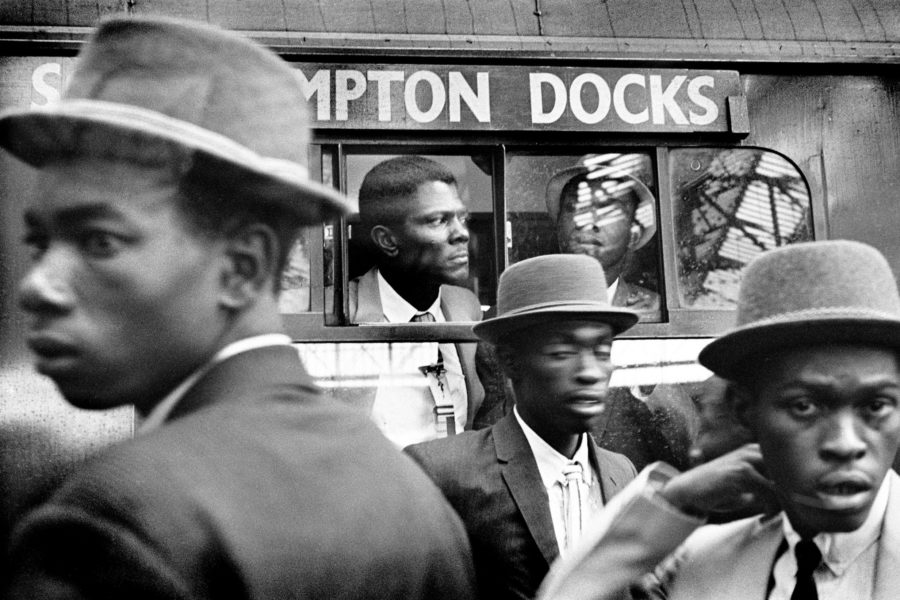

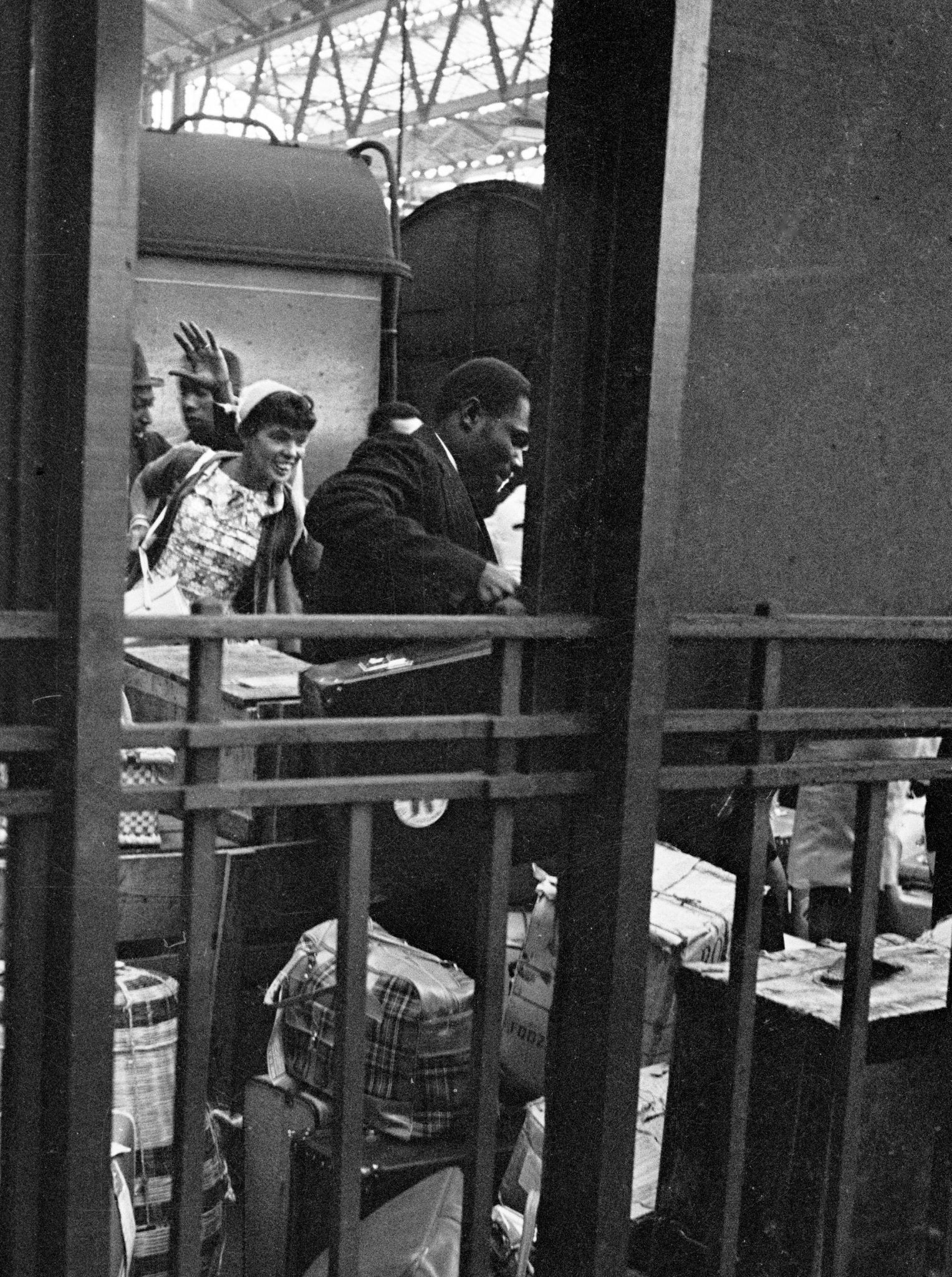

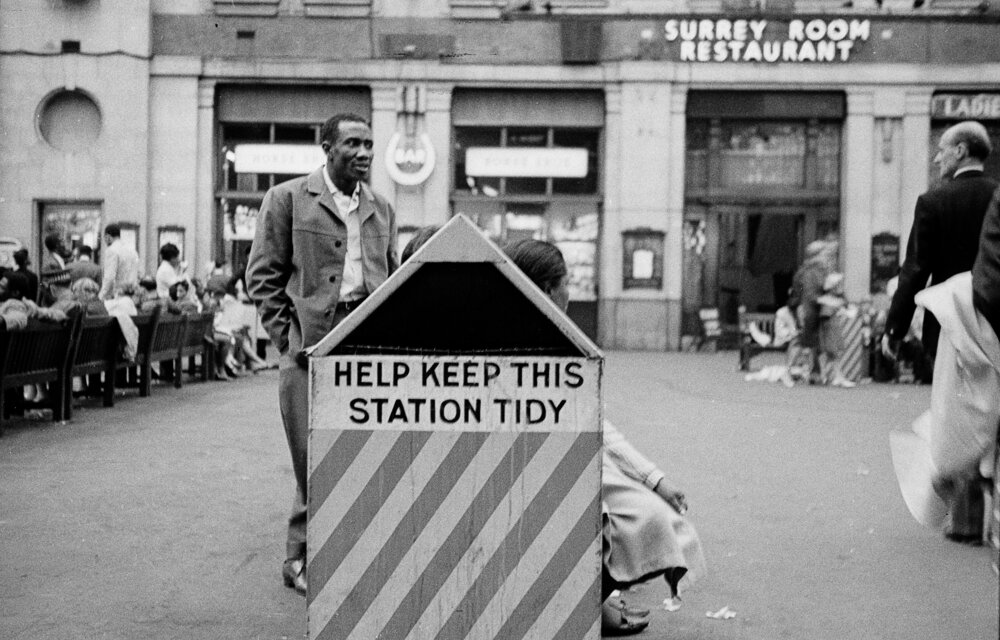

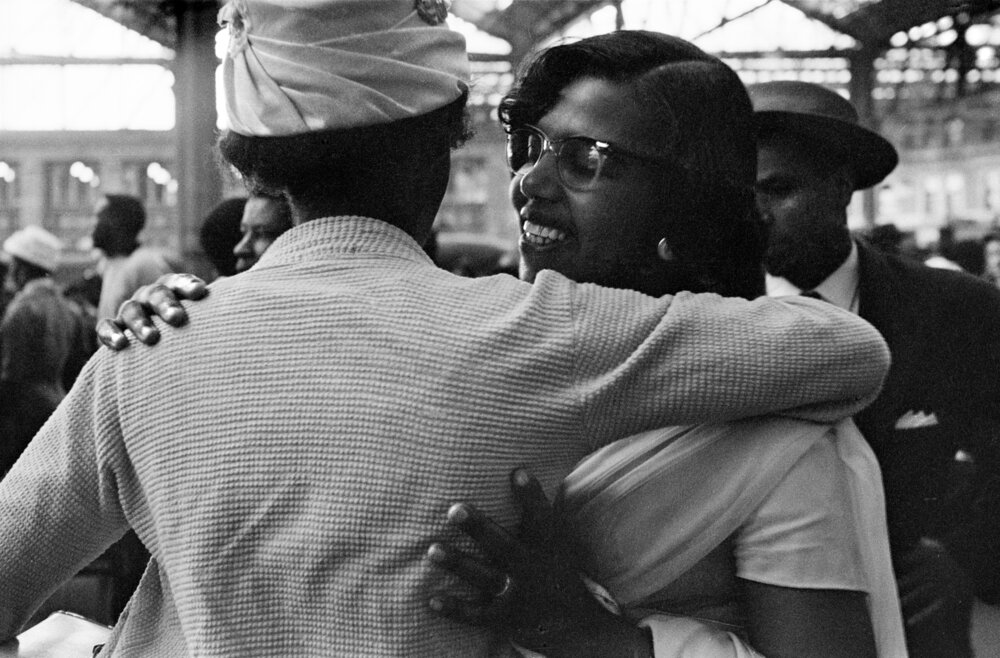

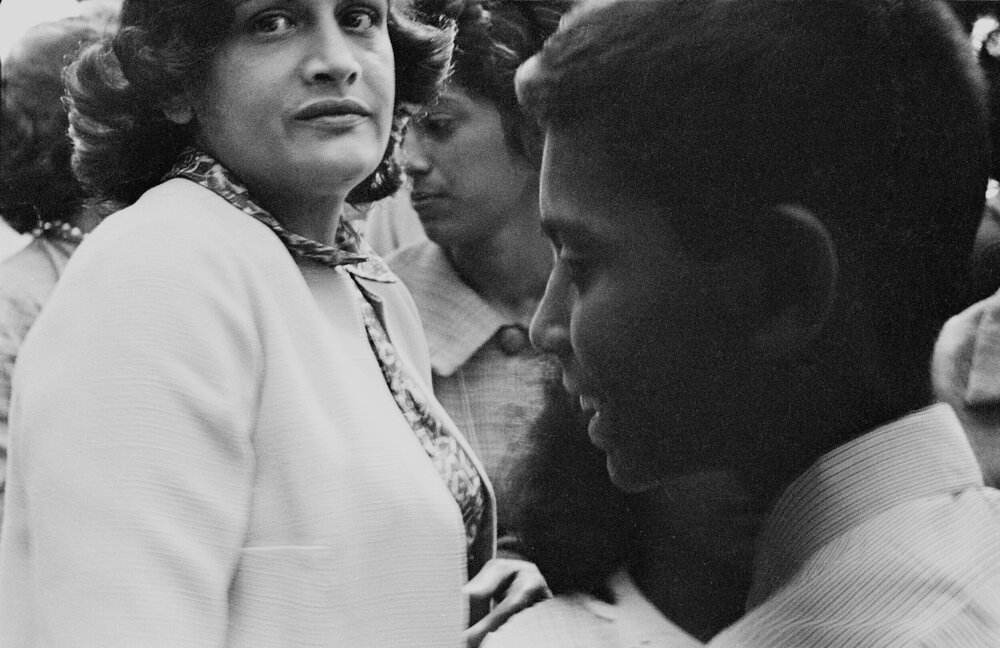

“In the early Spring of 1962, I decided that there might be a good photo-opportunity to bus it down to London’s Waterloo Station and take some photographs of the final West Indian arrivals before the British Government Immigration Act 1962, came into force, writes Howard Grey. He was 20-year-old.

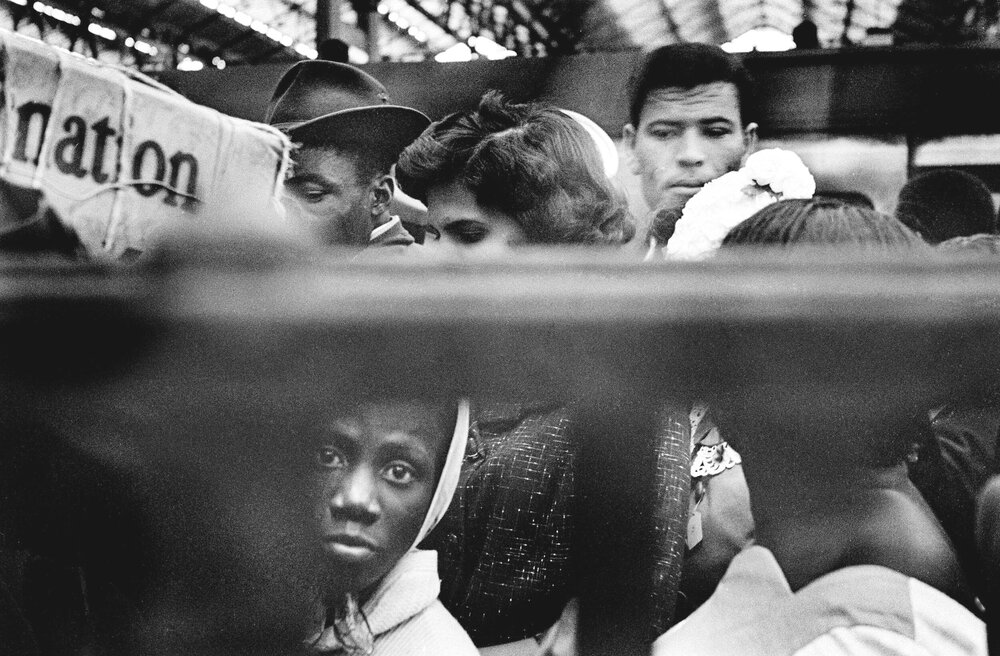

Who were these people then? What happened next? So many stories. If this was you or is someone you know, please get in touch. For now, let’s look at Howard’s incredible pictures that capture a momentous time in so many lives, and imagine the stories between.

The pictures would remain unseen for decades. As Howard notes: “Sadly the light conditions there were so bad that no printable negatives could be achieved – until 50 years later, when the introduction of digital scanners could restore this now historic collection for posterity.”

He adds:

“If you’re a photographer, you know those negatives are never going to print… You could see the highlights, the shirts or their eyes, and the roof windows in the station and the rest was dark. Very, very dark. Suddenly, I scanned them in and did three scans – one for the shadows, one for highlights and one for the mid-tones and they call came together. Myself and my sister… were screaming with excitement. ”

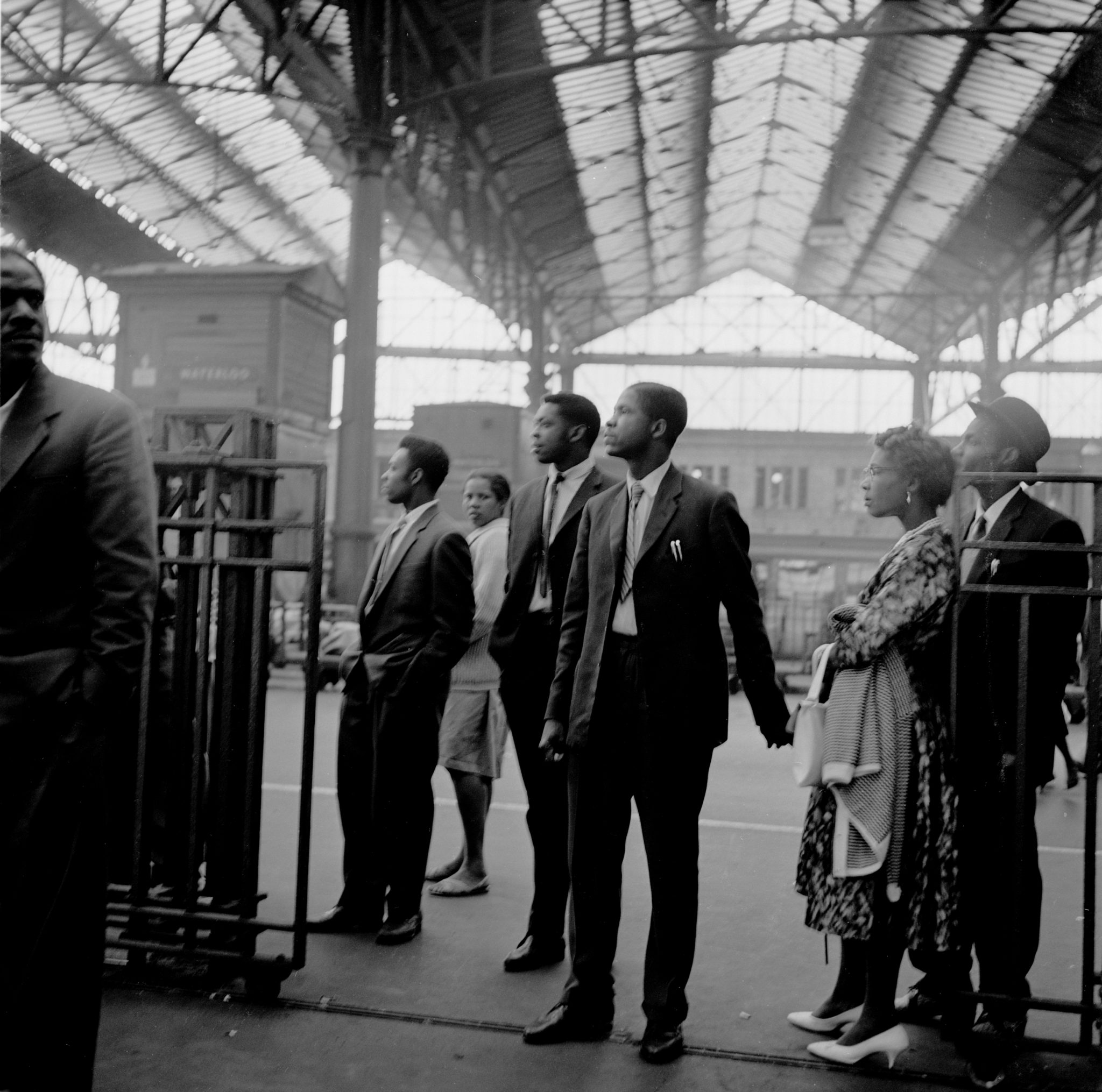

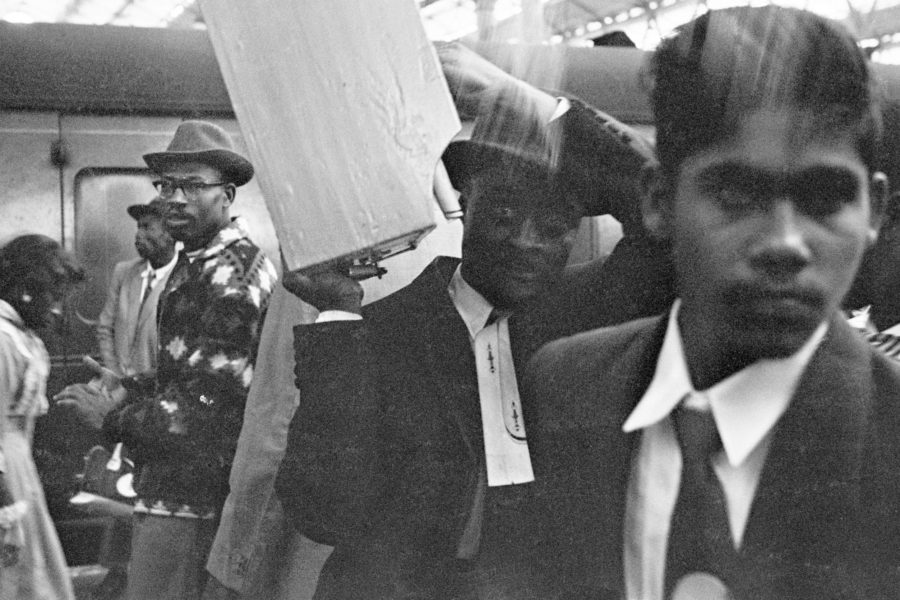

“I was the only photographer there and you could buy a platform ticket for two pennies, says Howard. “When I got there, everybody was waiting for the train to come in and I got shots of the train coming in, and [a news crew] was there … By the time I got the cameras out, I was standing amongst all the people, so I just spun round taking pictures.

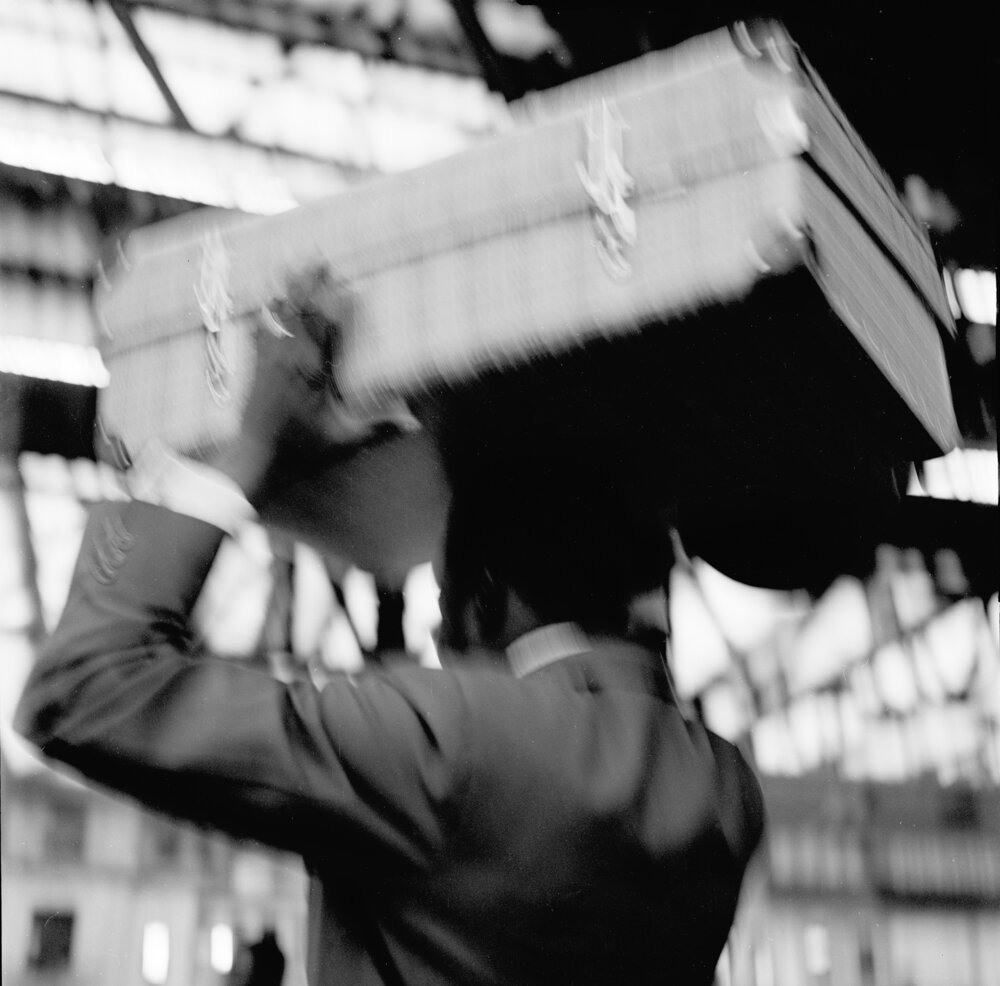

“I had cameras – a Leica and a Rolleiflex – I just put some film in, I never used to shoot with flash, which I always thought was a better way of doing things. I took about 40 shots in total.”

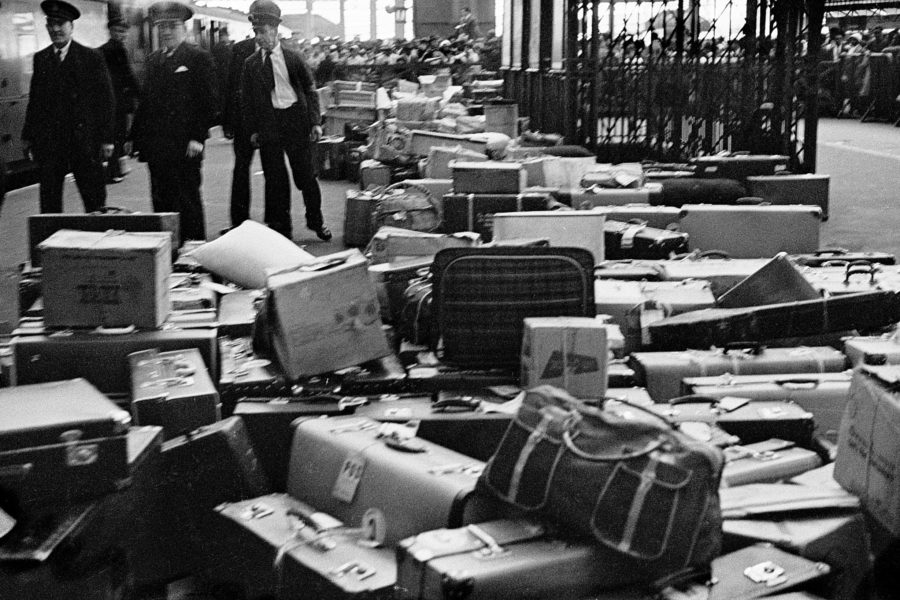

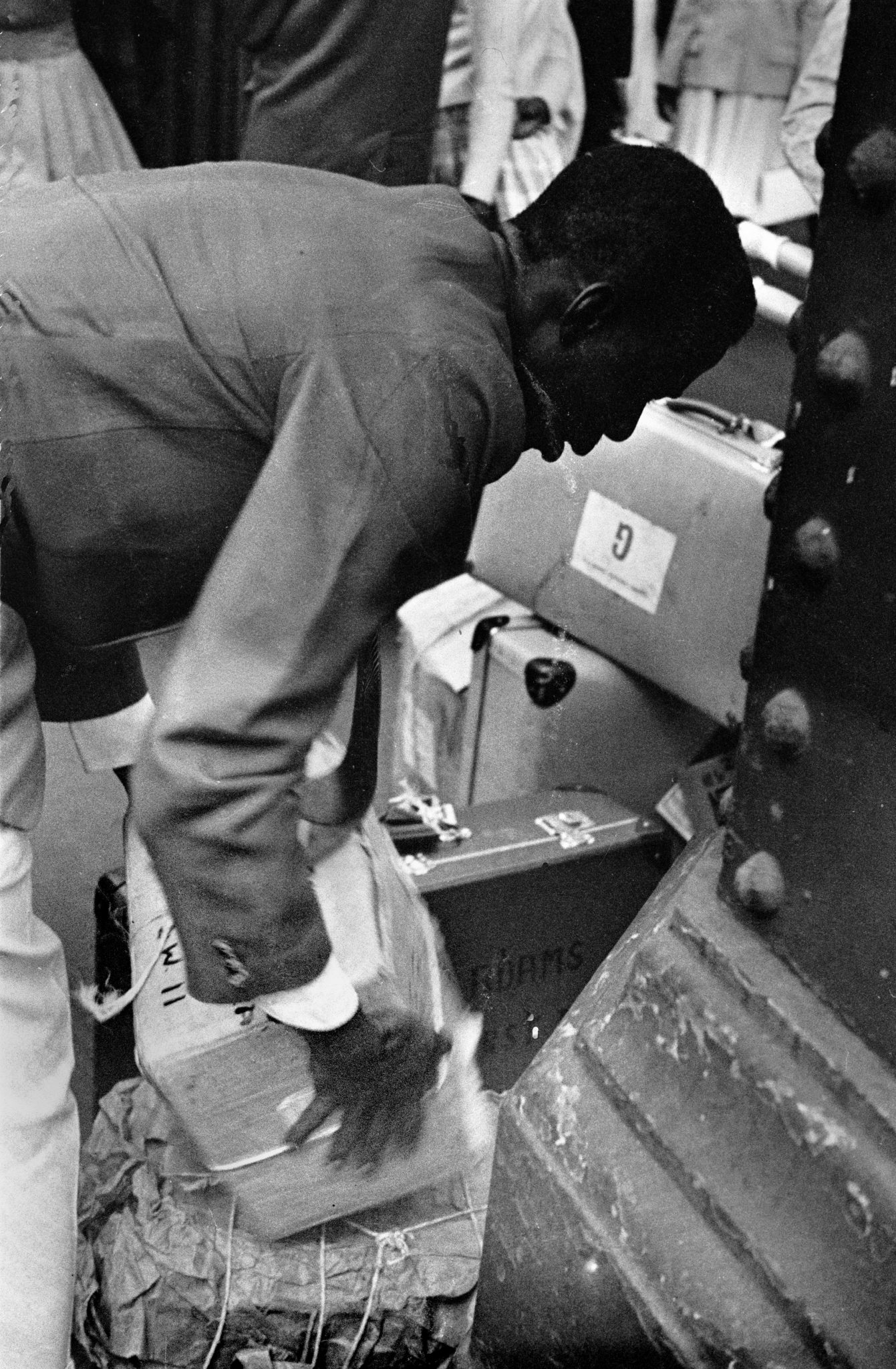

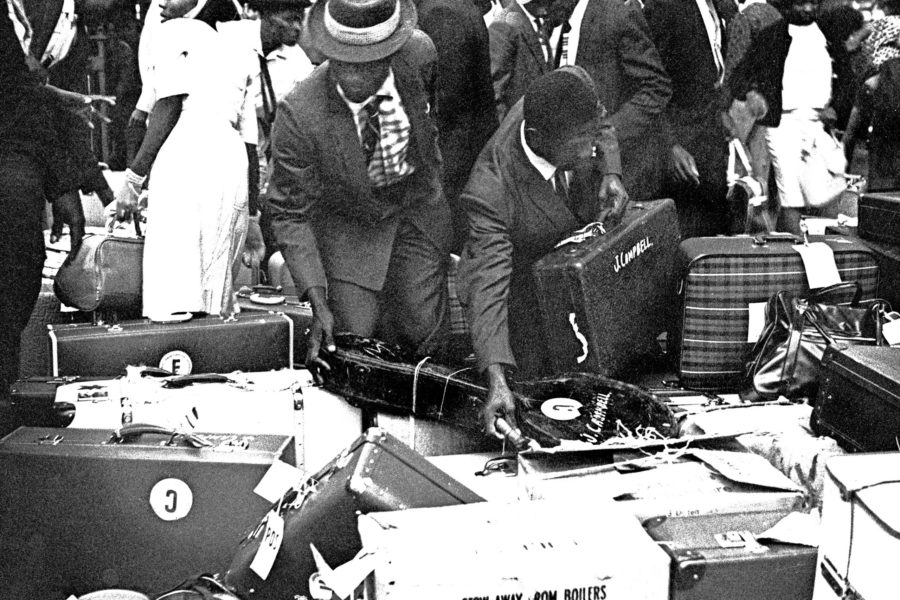

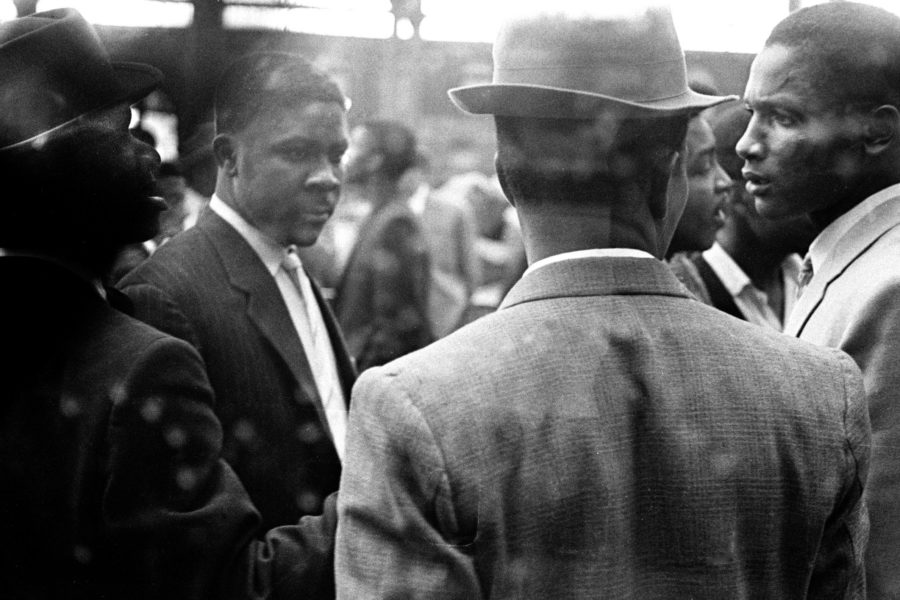

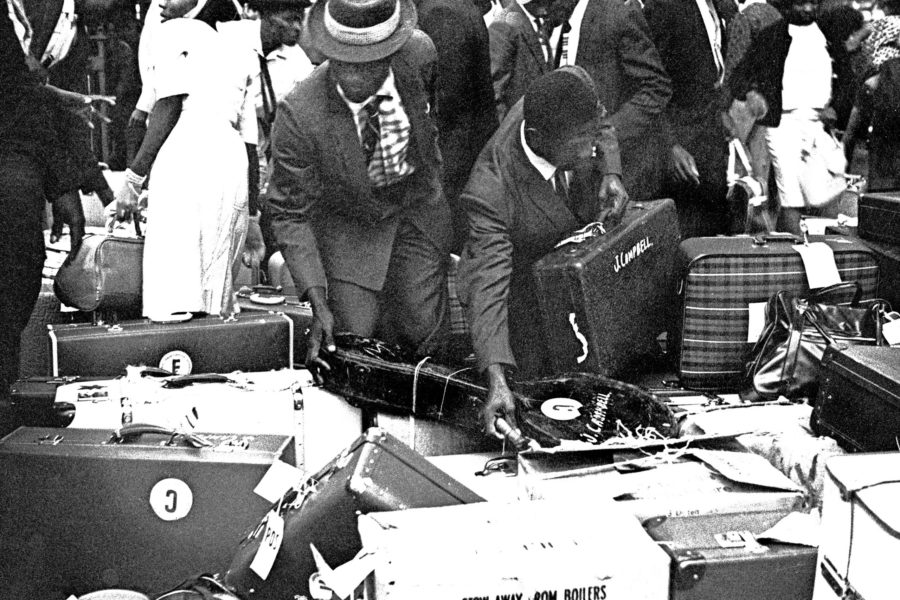

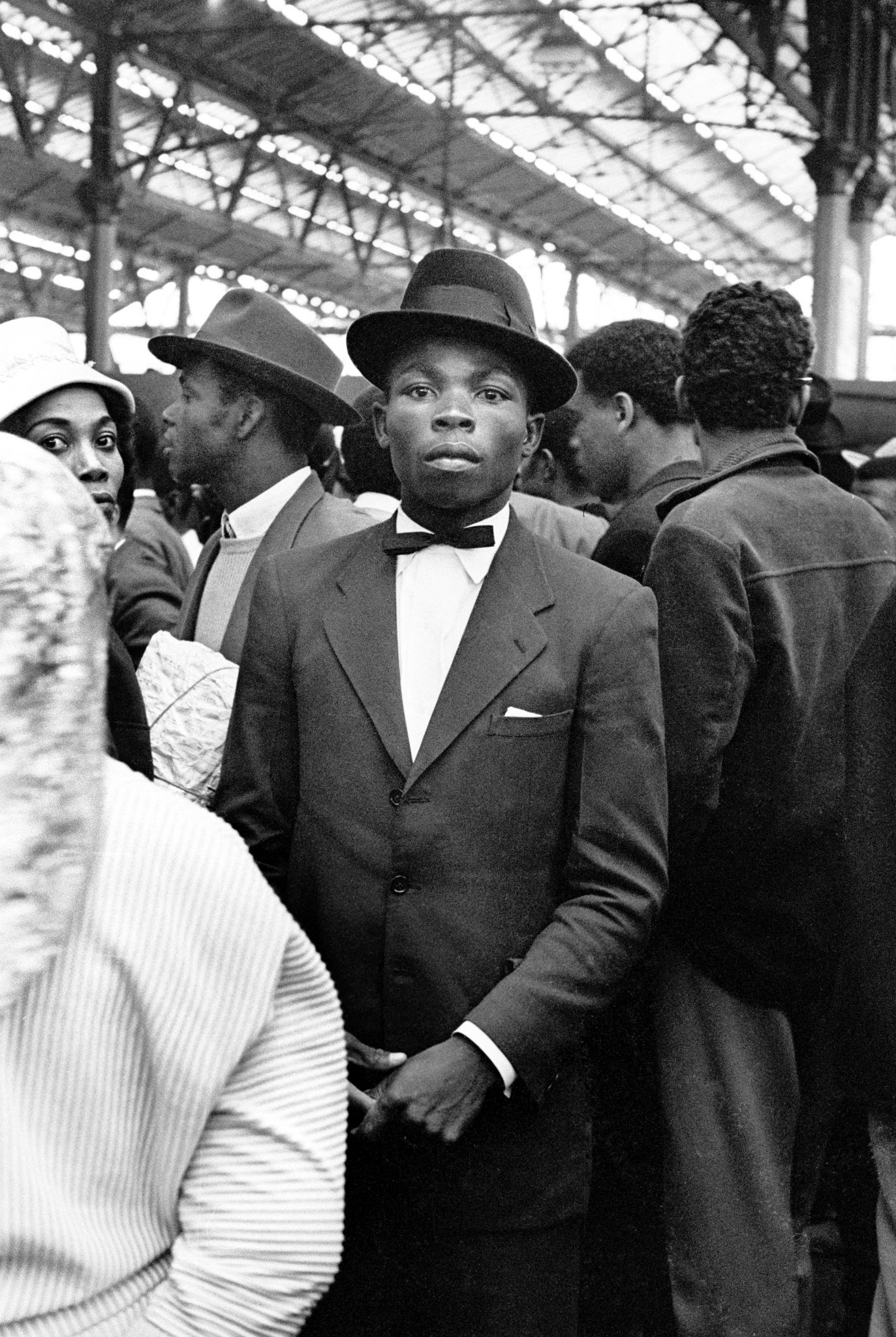

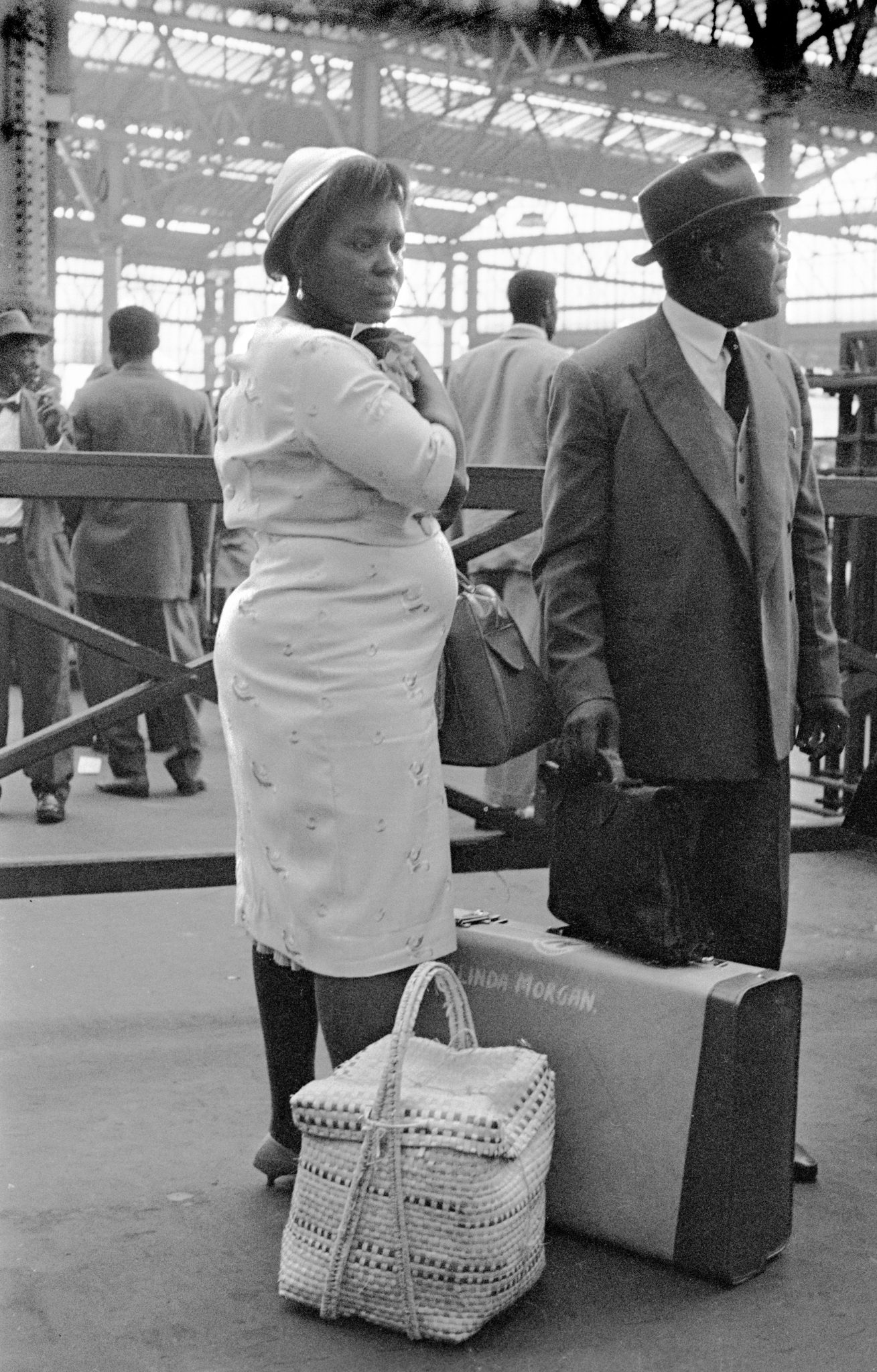

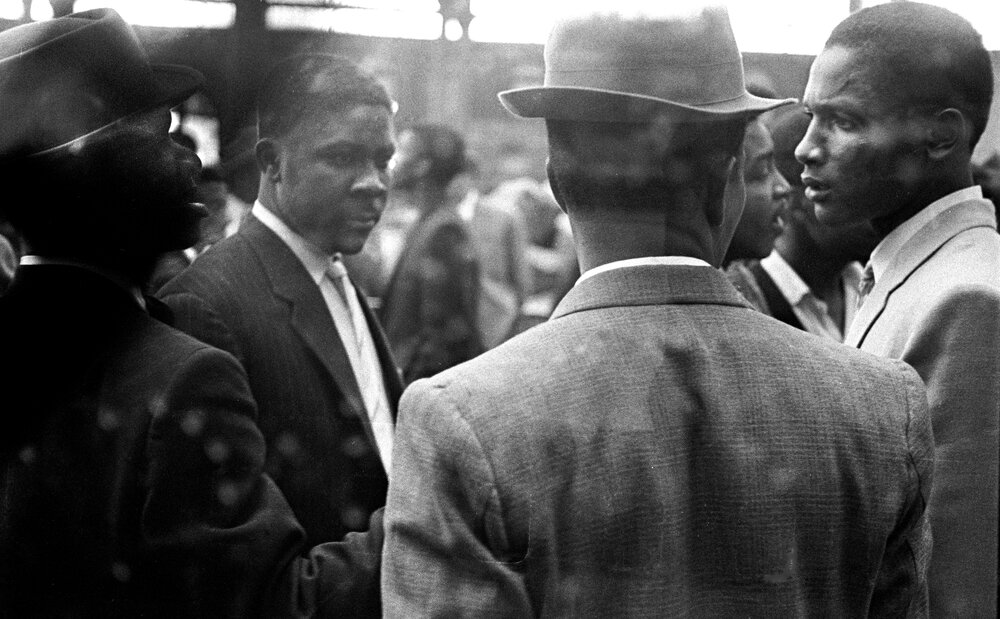

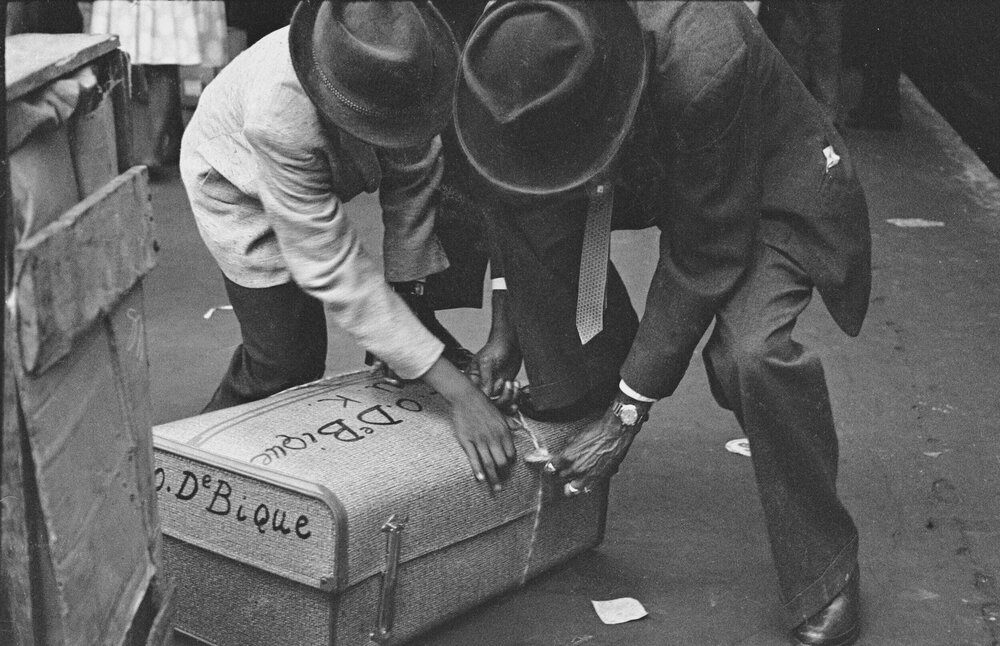

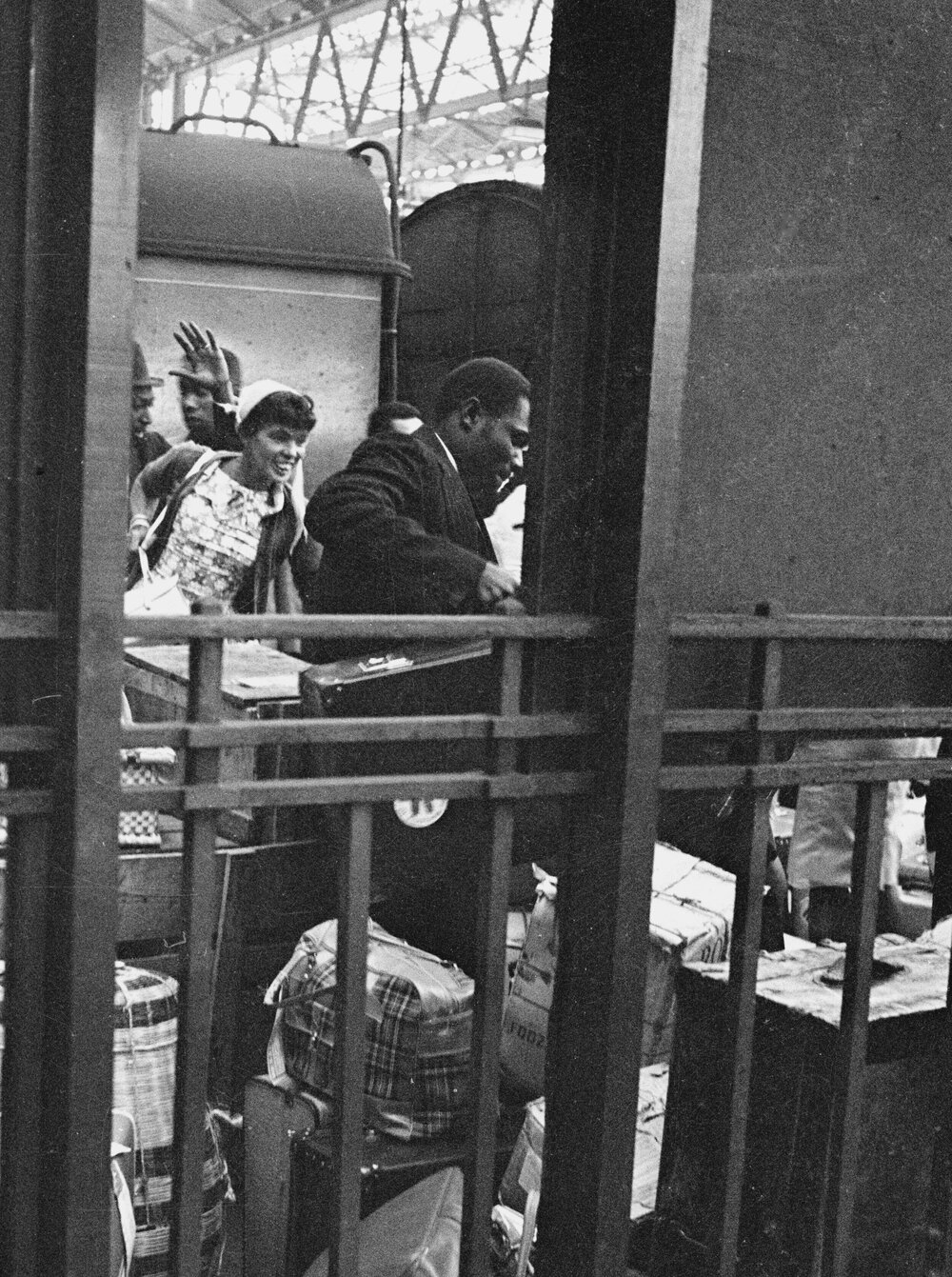

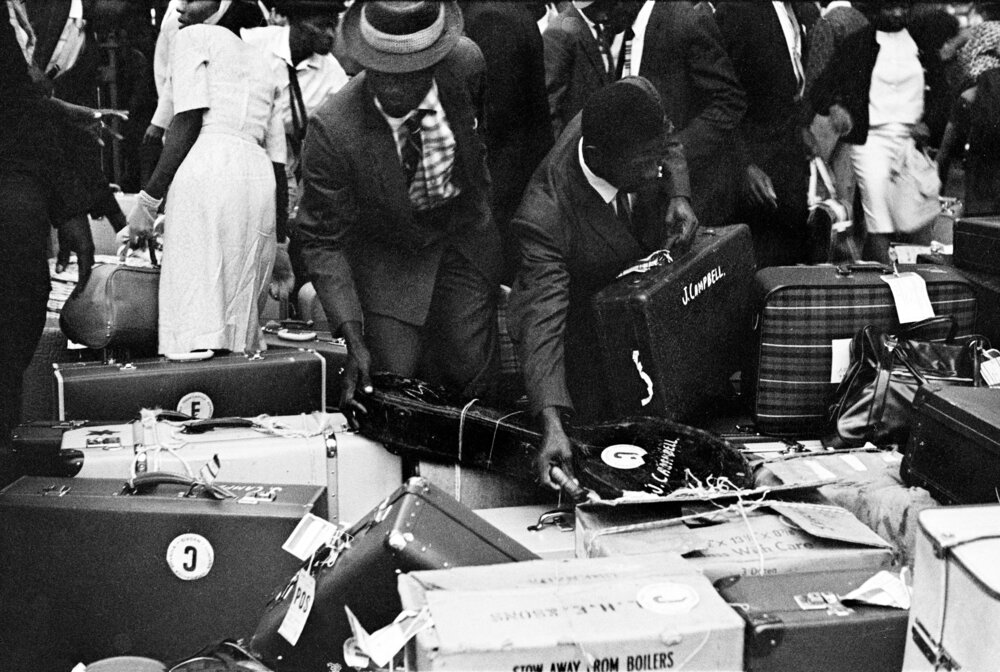

“The atmosphere was quite subdued, quiet. You’ve got the laughter … they could see their relatives coming but there were barriers. The barriers stopped them going up to them because of all the luggage. All the luggage was taken out of the goods van as they called it and was put on the platforms … But it was very quiet. The whole thing was apprehensive.

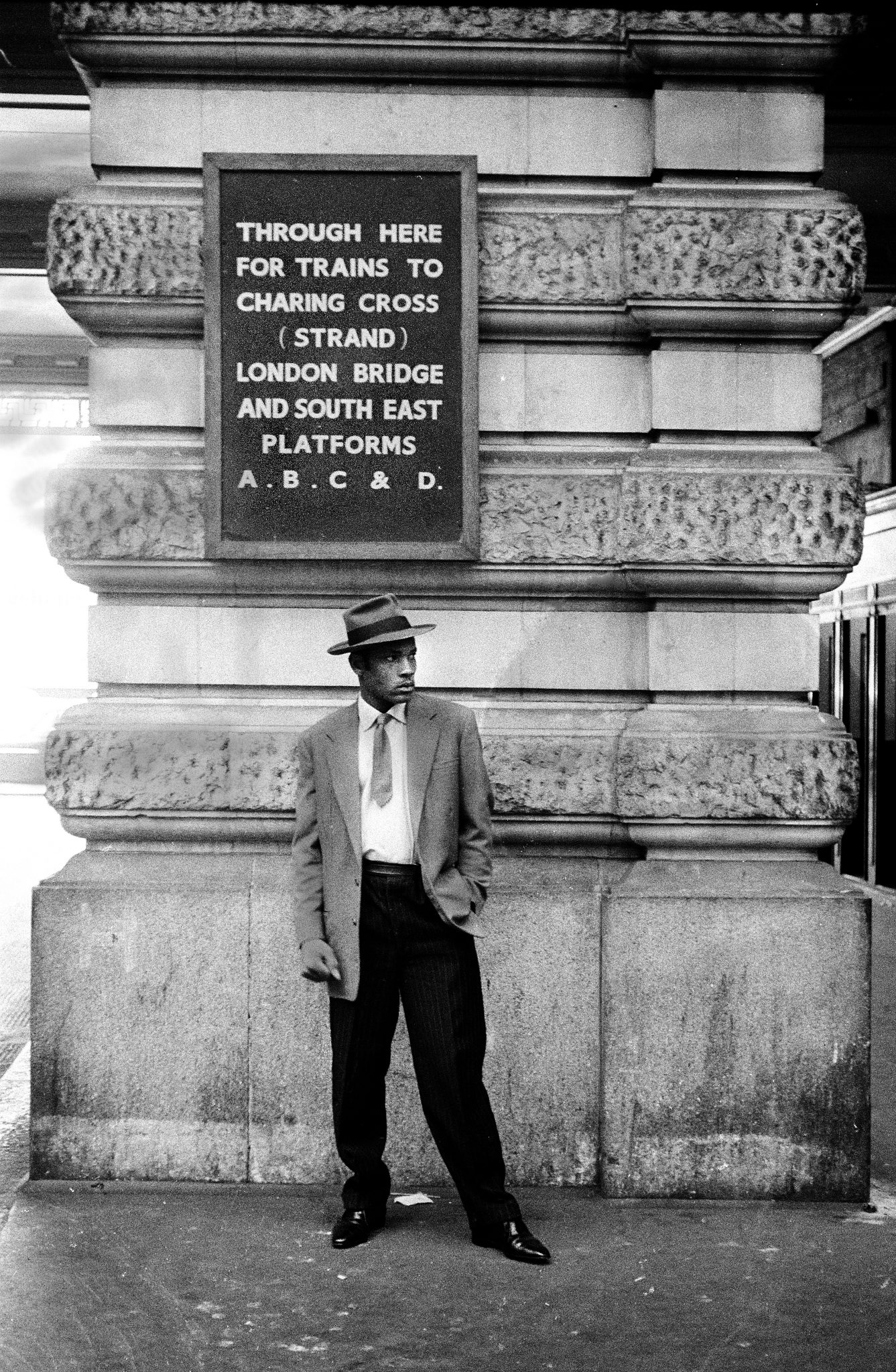

“The people there to greet them probably hadn’t seen them for eight years, 10 years … the apprehension of three, four weeks of travelling that the passengers had. They put all their Sunday clothes on because they were coming to London where everybody was smart.

“What I’ve since discovered is these young men were the sons of middle-class people in the West Indies. They were doctors or solicitors or big businessmen, so they paid for their children to go and have a new life, for the most part.”

– Howard Grey

The Windrush Story

In 1948, the Empire Windrush, en route from Australia to England docked in Kingston, Jamaica, ostensibly to pick up servicemen who were on leave. The ship was no where near full, and so an opportunistic advert was placed in the Jamaican newspaper The Gleaner offering cheap transport (£28) on the ship for anybody who wanted to come and work in England. When the ship set off all of the three hundred berths on board were taken and a further 192 men slept on the deck.

When the ship arrived in Tilbury on the 22nd June newspapers reported that launches were sent out taking intrigued sightseers to peer at the Jamaican newcomers. Colonial Office officials went out to the ship to welcome the Jamaicans although reporters were banned from going on board. Mr Ivor Cumming of the Colonial Office, black himself, told the passengers of the difficulties that were bound to lie ahead and asked for their help and cooperation. Among the 492 passengers was the 22 year old Sam Beaver King who went on to become the first black Mayor of Southwark. There were also the calypso musicians Lord Kitchener, Lord Beginner, Lord Woodbine and Mona Baptiste.

The next day the Manchester Guardian wrote:

What were they thinking, these 492 men from Jamaica and Trinidad, as the Empire Windrush slid upstream.

Standing by the rail this morning high above the landing-stage at Tilbury, one of them looked over the unlovely town to the grey-green fields beyond and said, “If this is England I like it”

It was curiously touching to walk, along the landing stage in the grey light of early morning and see against the white walls of the ship row upon row of dark, pensive faces looking down upon England, most of them for the first time. Had them thought England a golden land in a golden age? Some had, with their quaint amalgam of American optimism and African innocence.

While the Daily Mirror noted:

The Jamaicans lined the decks and because no Pressmen were allowed on board they shouted to me:-

“We won’t be disappointed in England. Nothing could be as bad as what we have left. We want to help England back on its feet again. We’ll work as hard as anyone for you. Give us a chance They wouldn’t even let us work in Jamaica.”

Flight Lieutenant J. H. Smythe, a native of Sierra Leone and a member of the Colonial Office Welfare Department was on board as they travelled from the West Indies. Towards the end of the voyage he asked to split the passengers into three groups.

Group One: 52 who are volunteering for the Forces (these were sent off to a Wimpole Street hostel at a cost of £1 1s a week/

Group Two: 204 who have friends in England

Group Three: Those with no jobs or any friends or relatives. These men were taken by bus to deep shelters on Clapham Common (cost 2s 6d a week). They were then told to go to the Coldharbour Lane Employment Exchange in Brixton (about a mile away) to look for work.

The Empire Windrush

The Empire Windrush was originally a German ship called the MV Monte Rosa. It was used by the Nazi regime as part of the the Strength Through Joy programme that provided leisure activities and cheap holidays as a way of promoting fascist ideology. During the war she acted as a troopship for the invasion of Norway in April 1940.

Two years later, she was used for the deportation of Norwegian Jewish people, carrying a total of 46 people from Norway to Denmark. Of the 46 deportees carried on Monte Rosa, all but two died in Auschwitz concentration camp. In 1946 she was assigned to the British Ministry of Transport and converted into a troopship and renamed HMT Empire Windrush at the beginning of 1947.

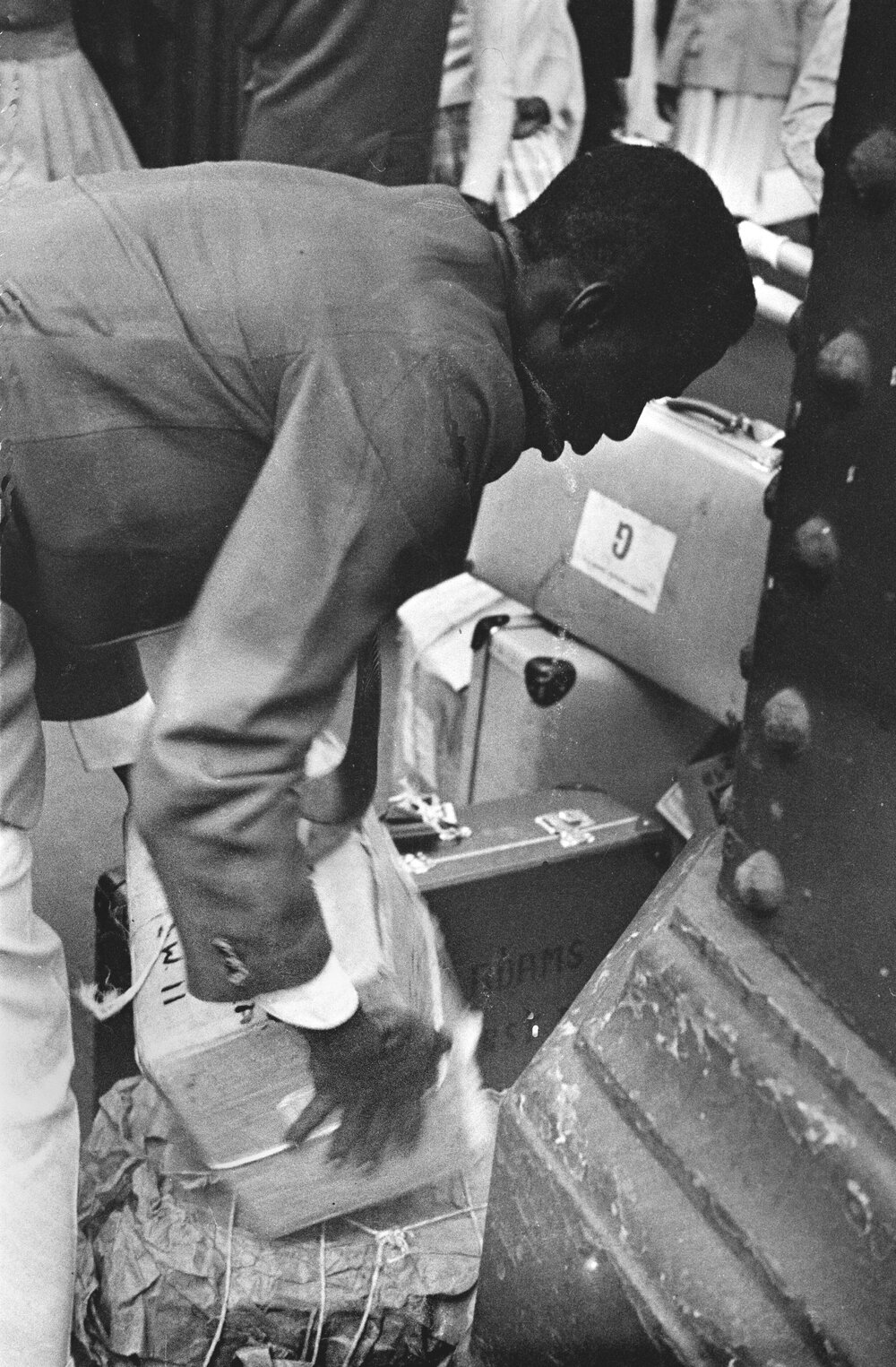

The last West Indian immigrant arrival before the UK Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962 came into force. Location: London, England – Walerloo Station from Southampton Docks 1962. Windrush.

The last West Indian immigrant arrival before the UK Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962 came into force. Location: London, England – Walerloo Station from Southampton Docks 1962. Windrush.

The last West Indian immigrant arrival before the UK Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962 came into force. Location: London, England – Walerloo Station from Southampton Docks 1962. Windrush.

If this is you or someone you know in any of thee pictures, please get in touch. We’d love to hear from you.

All pictures copyright of Howard Grey.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.