I love people. Everybody. I love them, I think, as a stamp collector loves his collection. Every story, every incident, every bit of conversation is raw material for me. My love’s not impersonal yet not wholly subjective either. I would like to be everyone, a cripple, a dying man, a whore, and then come back to write about my thoughts, my emotions, as that person. But I am not omniscient. I have to live my life, and it is the only one I’ll ever have. And you cannot regard your own life with objective curiosity all the time…

– Sylvia Plath

The first recording of Sylvia Plath reading her poetry was published in 1975. A second was issued on cassette and vinyl in 1977. In 2010, Sylvia Plath – The Spoken Word was produced by the BBC and The British Library. Many of us have heard of Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) – but have you heard her read her poems?

Plath was the American poet who began writing journals at the age of eleven and continued documenting her life as confessional until her suicide. She left behind her husband Ted Hughes, their two children and words.

Suicide is hard to talk about. How did a romantic woman enraptured by life come to end her own at just 30?

Knowing the dates of Plath’s mortal existence, we can frame a complete story. There’s a temptation to attribute to her a morbid outlook that dogged her entire life. But people don’t live just in the present, the past or the future. The story does not run from cradle to grave. We think of our lives from where we are now. The view is more kaleidoscopic. You can read Plath’s ode to love and her haunting line in Lady Lazarus: “Dying / Is an art, like everything else / I do it exceptionally well” and know they are thoughts of the same person at different moments, one utterance no more meaningful than the other.

1940 : Winthrop , Massachusetts , U.S.A – Sylvia Plath dressed to help the nurse who was caring for her father Otto Plath , who died shortly after this picture was taken

You can hear the teenage Plath enjoying life and wondering what happens next:

“Somehow I have to keep and hold the rapture of being seventeen. Every day is so precious I feel infinitely sad at the thought of all this time melting farther and farther away from me as I grow older. Now, now is the perfect time of my life…

“I am afraid of getting older. I am afraid of getting married. Spare me from cooking three meals a day — spare me from the relentless cage of routine and rote.”

You can read her observations jotted in one of her many journals. This from The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath (via):

There are times when a feeling of expectancy comes to me, as if something is there, beneath the surface of my understanding, waiting for me to grasp it. It is the same tantalizing sensation when you almost remember a name, but don’t quite reach it. I can feel it when I think of human beings, of the hints of evolution suggested by the removal of wisdom teeth, the narrowing of the jaw no longer needed to chew such roughage as it was accustomed to; the gradual disappearance of hair from the human body; the adjustment of the human eye to the fine print, the swift, colored motion of the twentieth century. The feeling comes, vague and nebulous, when I consider the prolonged adolesence [sic] of our species; the rites of birth, marriage and death; all the primitive, barbaric ceremonies streamlined to modern times. Almost, I think, the unreasoning, bestial purity was best. Oh, something is there, waiting for me. Perhaps someday the revelation will burst upon me and I will see the other side of this monumental grotesque joke. And then I’ll laugh. And then I’ll know what life is.

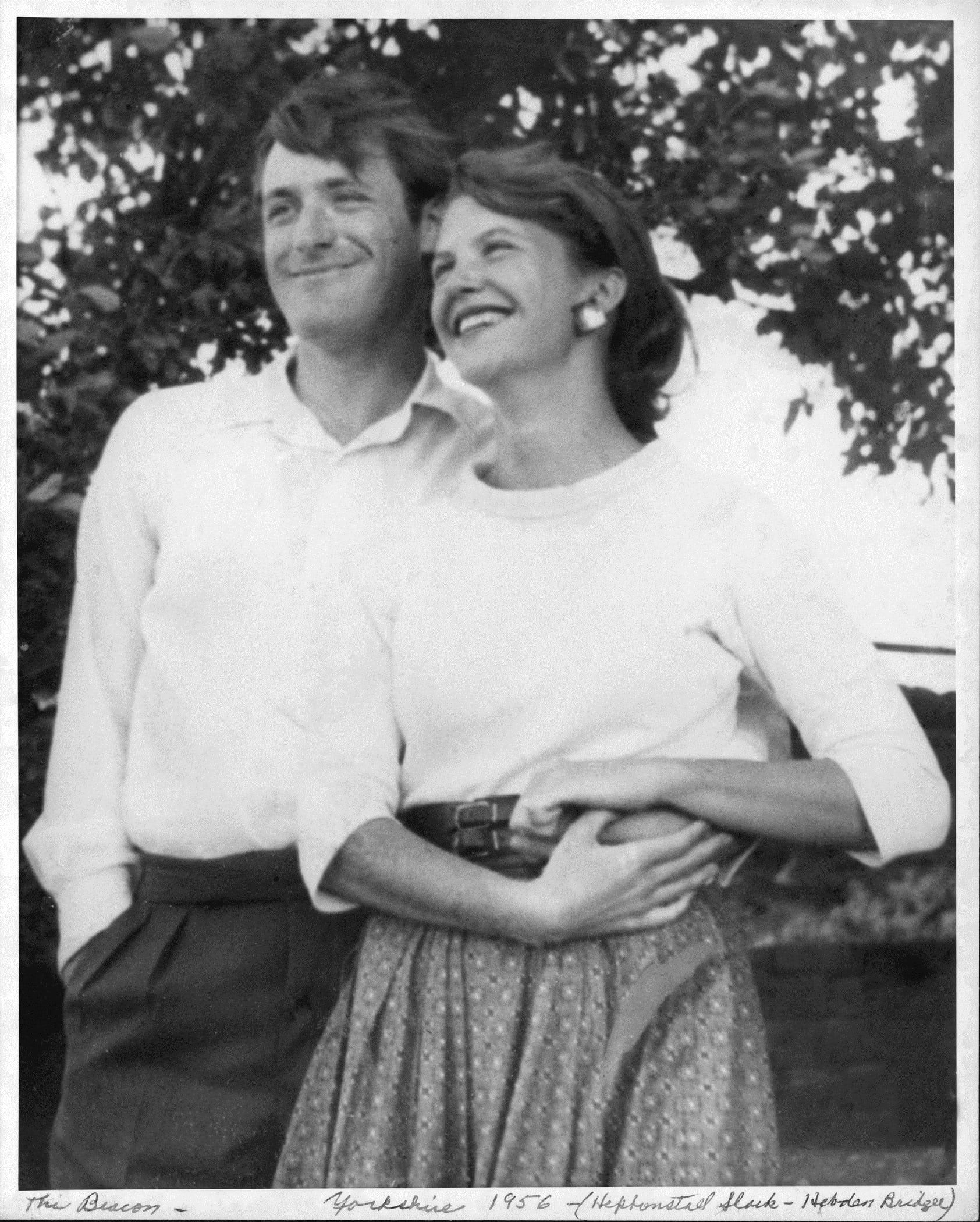

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath in Yorkshire, UK, 1956

Photograph: Harry Ogden/Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts

The more we read, the more confused the neat lineal progression from birth to death becomes. As James Parker notes in The Atlantic: “Her short life has been trampled and retrampled under the biographer’s hoof, her opus viewed and skewed through every conceivable lens of interpretation.”

We know Plath’s broad story, and have possibly seen her art, but how many of us have heard the voice of the woman who wrote the autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, The Colossus, the only collection of poems Plath published in her lifetime, and Ariel, a collection of poetry published two years after her death, the text found on the kitchen table by her body?

Beneath is Plath reading her own words.

Listen : Sylvia Plath Reads Ariel & Other Poems:

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.