Though his name is hardly known today, photographer Edwin Rosskam did at least as much to bring about the state of modern media as Walter Cronkite or Edward R. Murrow. Working behind the camera and the editor’s desk in the early 1940s for the Federal Farm Security Administration and several publishers earned Rosskam little in the way of recognition, though some few photographers, like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, who worked for the FSA did become famous.

Yet Rosskam was instrumental in the development of “our present concept of photo-journalism,” as he explained himself in a 1965 interview. The word itself, Rosskam claimed, was one “I believe I first brought into current use….” It’s not an empty boast. On returning to the US in the 1930s from time spent photographing in French Polynesia, Rosskam discovered the Depression happening, ran out of money, and pitched “the notion,” he says “together with my wife [Louise] to do a picture page once a week with a picture story” for the Philadelphia Record.

Before Life or Look magazines and their scores of imitators, “there were picture stories… that in turn led to other developments,” such as an entire genre in the 1930s/early 1940s of “works combining photographs and text,” Buckeye Muse writes, “with documentary purpose of exploring social topics and recording—and sometimes celebrating—American life.” Most of these books were produced either using FSA photographs or work from former FSA photographers. Rosskam pitched and edited a hallmark of the genre, Sherwood Anderson’s 1941 Home Town, in the same year that “an exceptionally powerful work of photo-text” appeared: the Richard Wright-penned, Rosskam-photographed 12 Million Black Voices.

In the text, “Wright’s vigorous portrayal of life under American racism combines with the gritty photos to create a work that still packs a punch nearly eighty years later” and stands in stark contrast to the breezy tone of Anderson’s short picturesque essays, which biographer Walter Rideout describes as “a compound of nostalgia and wide-traveled observation.” Wright instead begins with origins of the slave trade on the African continent and works his way up, in four dense, passionate chapters, to the Great Migration, in which “many fleeing the disenfranchisement, segregation, and racist violence of the Jim Crow South” found, Retronaut notes, “growing opportunities in the meatpacking and railroad businesses” in industrial cities like Chicago.

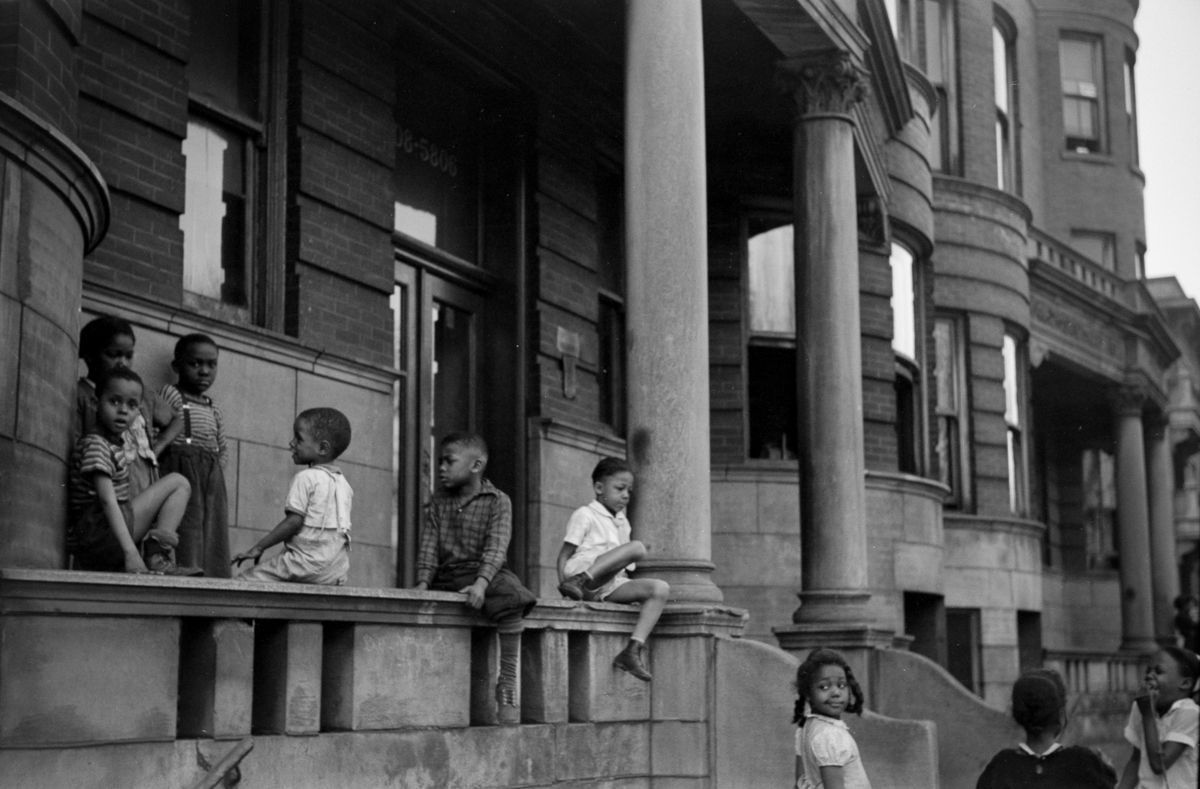

Violent resistance to the integration of mostly rural Black migrants from the south “combined with racist housing covenants, led to the de facto segregation of African-Americans into a narrow strip of run-down neighborhoods on the city’s South Side which came to be called the ‘Black Belt.’” And there began an incredibly vibrant culture informed by Southern sounds, tastes, and traditions but uniquely Chicagoan in character. The jazz and electric blues that would flow out of the city’s clubs and studios, for example, changed American culture permanently for the better.

But the people who created that culture would suffer the brunt of the economic decline after the post-war boom, and the South Side would sadly become known more for its poverty and gang violence. Wright made two contentions in his study: that poverty, violence, and discrimination had marked the essential experience of almost all Black life in the U.S., despite the few exceptions who “like single fishes… leap and flash for a split second above the surface of the sea”; and that such experience was “basic and centrally historical” to the formation of the country. Rosskam came up with the idea for the book, pitched it to Viking, and felt that Wright could not “have done a better job on the text.”

But Rosskam was unsatisfied with the book as a whole, perhaps because the photographs that made the editorial cut are so complementary to the ideas within, illustrating Wright’s downbeat history instead of providing contrast, which was, Rosskam thought, the best way of constructing a photo-journalistic text.

My thesis was then, and still would be if I were still producing such things, that the photographs should never be interfered with by saying the same thing in the text that you are in the text and vice versa. There are things you can only say with words, there are things you can say better with pictures than any other way. So the way to say the whole thing—put the things together in such a relationship to each other, that theoretically, at least, you read them jointly.

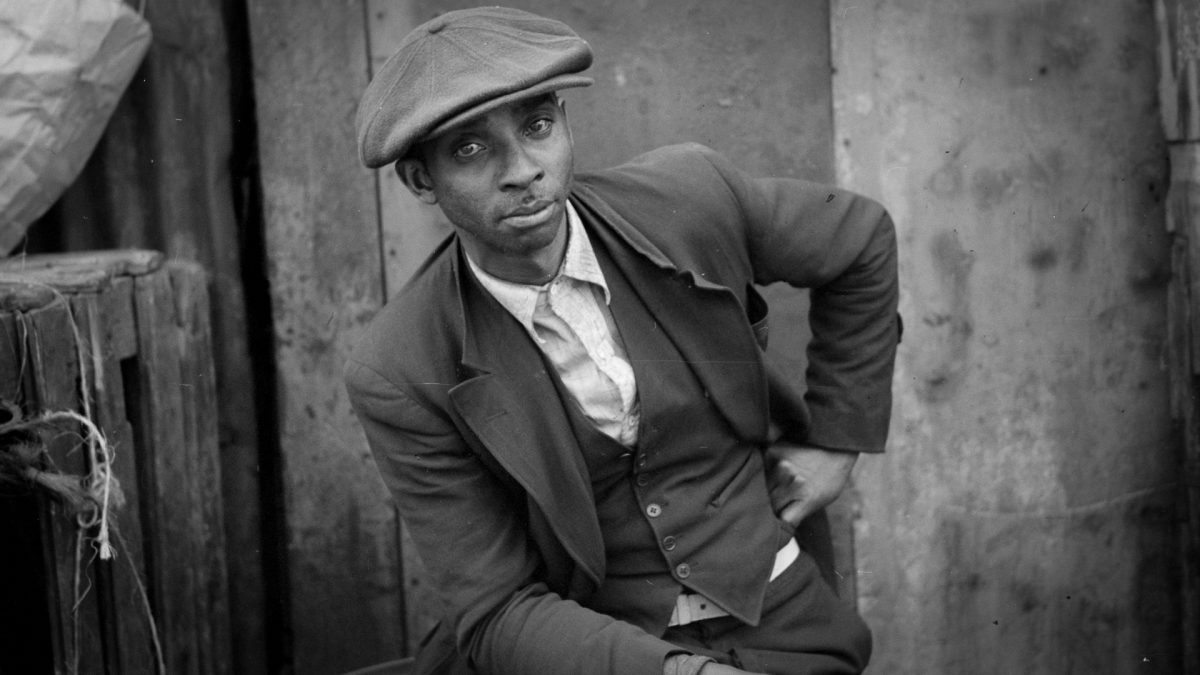

In the photographs here, however, which did not make it into the book, we see an entirely different Black Chicago, humanized, joyful, ordinary—a place not entirely dominated by misery. Perhaps these images provide better accompaniment to Wright’s jeremiad, a way of saying that in the midst of seemingly endless hardship, Black Americans have also thrived. Rosskam was resistant to the idea of “photographing poverty,” aware early on of the problem now referred to by the unfortunate term “poverty porn.”

Poverty and “desperation are dramatic,” he says, “It’s much easier to take an interesting picture of the dead cat on the ash can, than a picture of a live cat asleep….” Photographers, he says, were “always looking for drama and drama is a fluke.” In his photographs, Rosskam was interested in the everyday, in the fullness of people’s emotional lives, whatever their circumstances. In these images, mostly of children, he frequently catches his subjects’ eyes, and they gaze at the camera, and out at the viewer, from the space of decades past, with all the personal joys, fears, hopes, and aspirations Wright could not capture in his sweeping historical indictment of racism.

via Retronaut

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.