In 1929 almost everyone in the British film industry was convinced that the newfangled talking films would be nothing but a flash in the pan. But as the director Michael Powell once said of that time, “some flash, some pan”. Hitchcock knew before most that the era of silent films was over – “nobody wants ‘em,” he said to the aforementioned Powell, “they’re a dead duck”. So Hitchcock borrowed some German equipment and halfway through directing Blackmail he started to make a sound version of the same film and this, subsequently, became Britain’s first ‘talkie’.

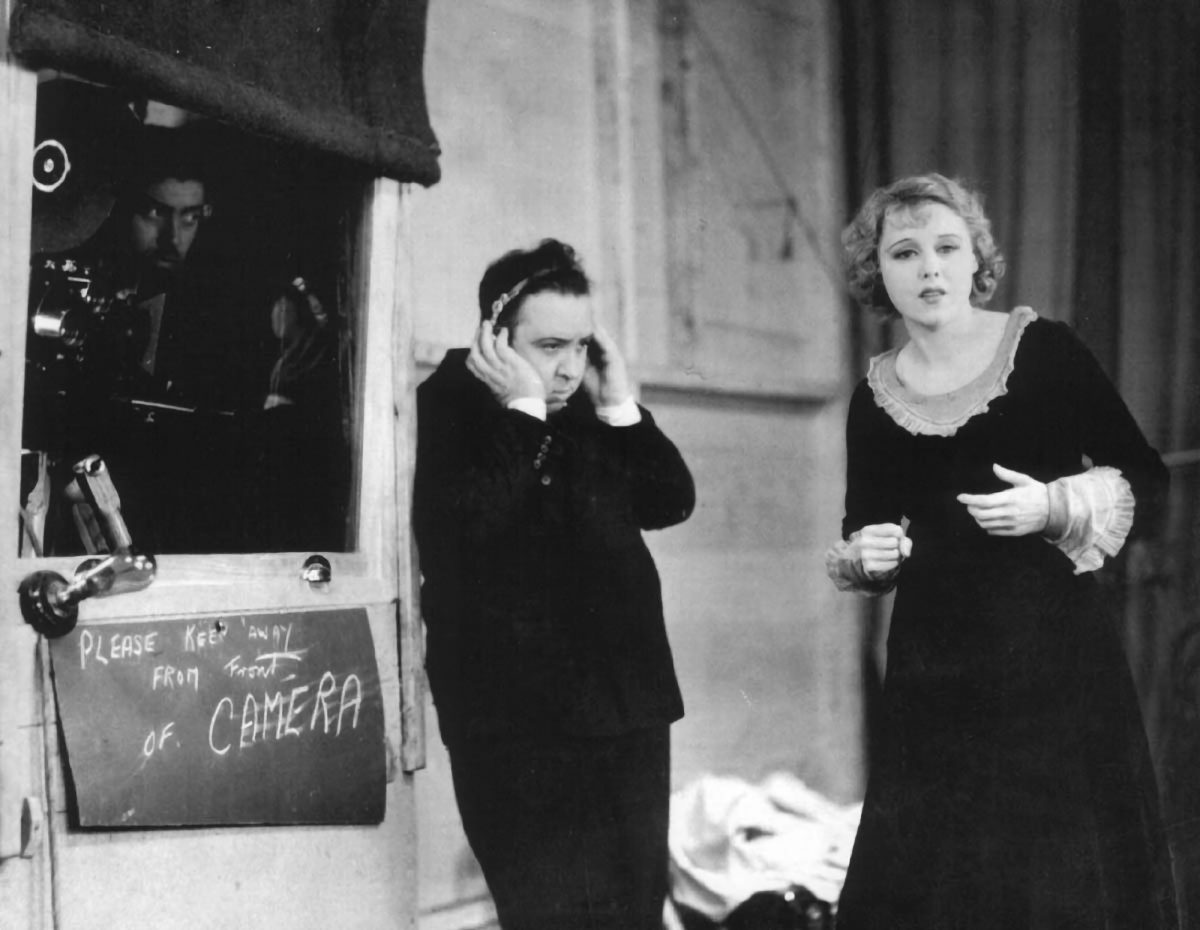

Some of the first words ever spoken on British film were uttered in a sound-test for Anny Ondra one of the stars in Blackmail and which featured a short conversation between Hitchcock and the Polish-Czech actress. Ondra certainly wasn’t hired for her authentic cockney accent and Hitchcock knew that her thick accented voice would not be suitable. Due to the unsophisticated sound-equipment, and in a situation that parallels similar scenes in Singin’ in the Rain made just 23 years later, he brought in the actress Joan Barry to dub live and off-screen, Ondra’s silent mouthing.

Alfred Hitchcock and Anny Ondra in 1929 during the production of Blackmail.

Ondra’s sound-test is notable not only as one of the earliest examples of a British talking film, but that it contained a rather cheeky joke. At one point Hitchcock asks Ondra why she’s bad and whether she had been with men. Ondra said “Oh no!” and, giggling, turned away from the microphone. Hitchcock replied, “You have not? Come here. Stand in your place otherwise it will not come out right… As the girl said to the soldier!”

It’s the first ever recorded version, at least of its equivalent, of an ‘..as the actress said to the bishop’ joke or in America the far more commonly used ‘That’s what she said’ line – both used as a punchline after an inadvertent double-entendre. As far as the British version is concerned it’s been said that the origins go back to the Edwardian period although I suspect that, in some form or other, it goes back centuries if not millennia. The first written instance that anybody has found in print appeared in 1928 in the first The Saint novel, written by Lesley Charteris called Meet the Tiger and published in 1928. Charteris’s examples, however, aren’t particularly risqué, for modern tastes anyway, and the Saint remarks include: “Isn’t it going to be fun? – as the bishop said to the actress”, and “I should be charmed to oblige you – as the actress said to the bishop.”

In a letter to The Guardian in 2010, a Nick Brockway wrote that he was told the phrase came from when:

The Bishop of Worcester and Lillie Langtry, the actress, were at one of those country house weekend parties. On Sunday morning, before church, the bishop and the actress went for a stroll in the garden. The bishop cut his finger on the thorn of a rose. Over lunch, Miss Langtry asked the bishop, “How is your prick?” He replied, “Throbbing,” and the butler dropped the potatoes.

Lillie Langtry achieved notoriety by being the mistress of King Edward VII. She died in Monaco in 1929.

By the Seventies, ‘said the actress to the Bishop’ jokes became far less common but were again popularised when Ricky Gervais, as David Brent in the The Office, frequently used the term. In the American version of same show Steve Carell adopted “that’s what she said” – the American equivalent – and again this spawned a resurgence of of the phrase which had fallen out of favour after its peak in the 1990s. The first recorded use of ‘that’s what she said’ is thought to have been around 1975 when an example of the phrase was spoken by Chevy Chase in an early Saturday Night Live sketch from the first series. A few years later it became used during the Wayne’s World skits on the same show but later again in the movie Wayne’s World. It has to be said that the American version is less funny partly because it is less mischievous as the British original that has connotations of establishment and religious hypocrisy. It also can’t be reversed, which enables anyone to say ‘as the Bishop said to the Actress’ if the double-entendre makes more sense that way.

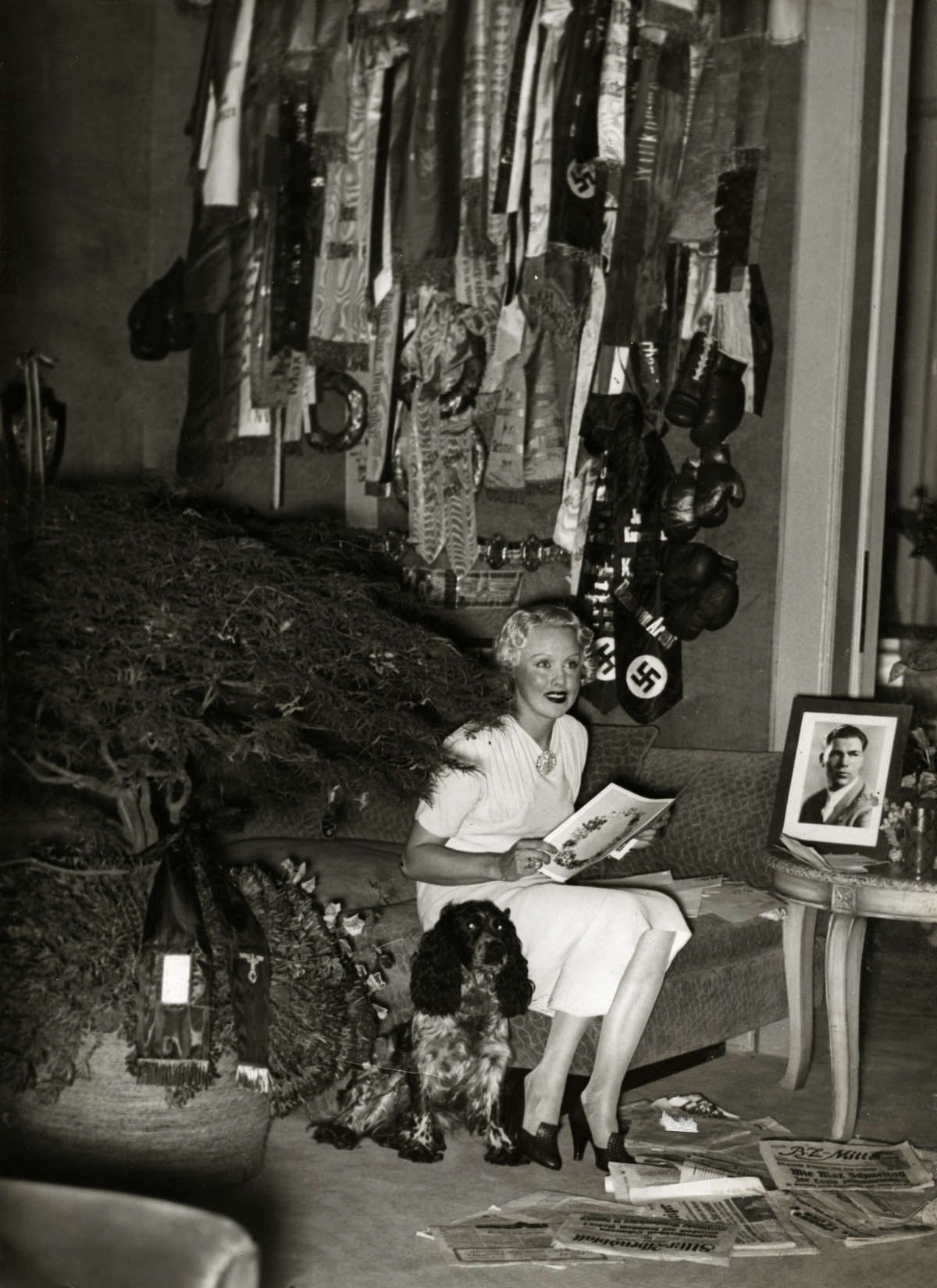

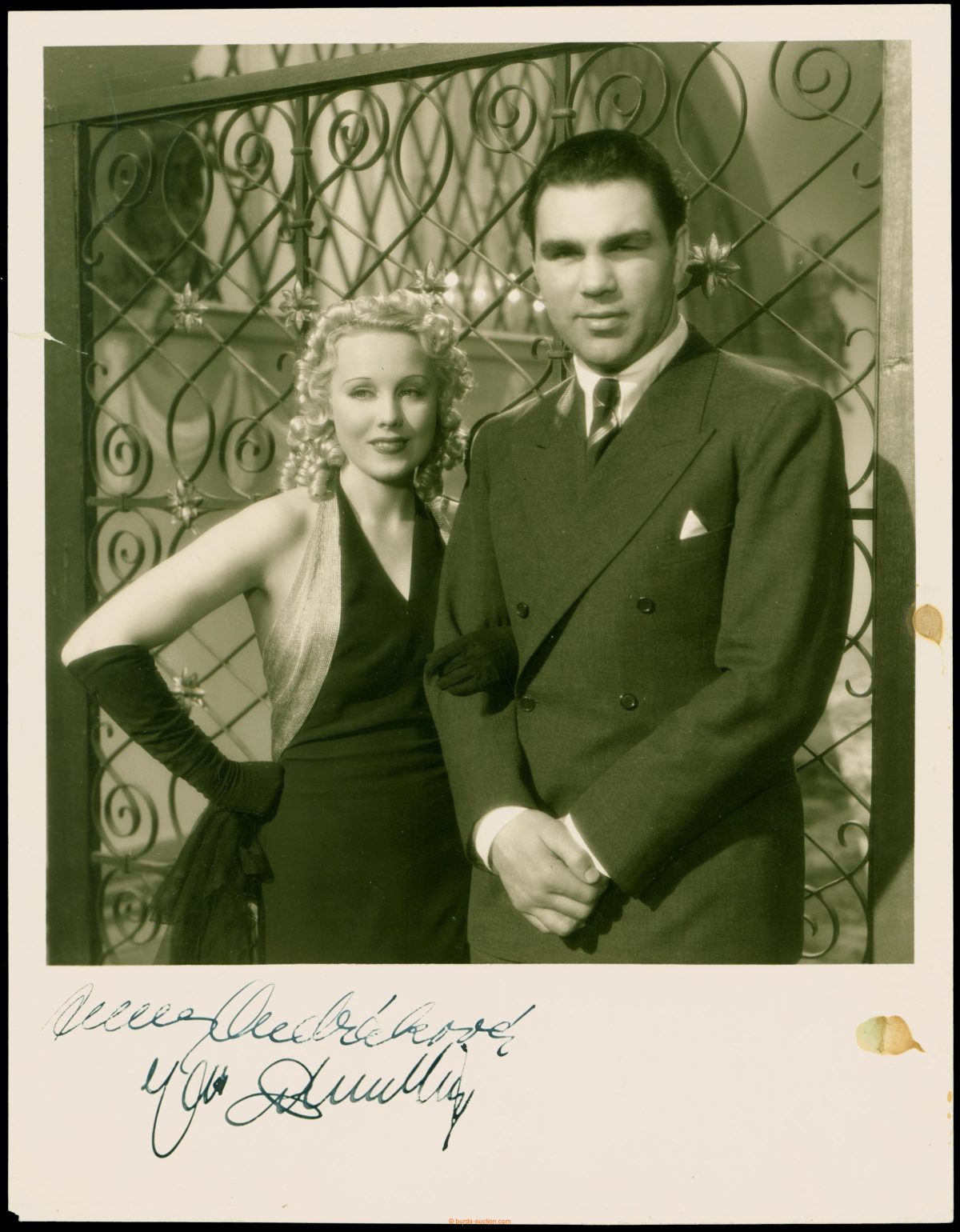

After the use of Joan Barry to dub her voice in Blackmail, it wasn’t particularly surprising that Anny Ondra, originally called Anna Sophie Ondráková, never made an English-language film again. The reason, however, wasn’t just for her foreign accent. On July 6, 1933, four years after the fateful Hitchcock sound-test, Ondra married German boxer Max Schmeling. Her new husband had been heavyweight champion of the world in 1930 until 1932 when he had lost to Jack Sharkey after a controversial 15th round decision. Schemeling, however, became a hero to the Nazis when, as the underdog, he beat the great black American boxer Joe Louis in 1936. Schmeling’s infamous victory “wasn’t only sport”, according to the Nazi weekly journal Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps), it was also “a question of prestige for our race”. Schmeling was feted throughout Nazi Germany and even appeared smiling next to Hitler and his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels in publicity photographs. In fact Anny Ondra had listened to the fight on the radio in Goebbels’s actual living room. “Stayed up all night,” Goebbels would report. “At 3 a.m. the fight begins. In round 12 Schmeling knocks out the Negro. Wonderful… The white man defeats the black man, and the white man was a German!”

Joe Louis and Max Schmeling

Anny Ondra at home

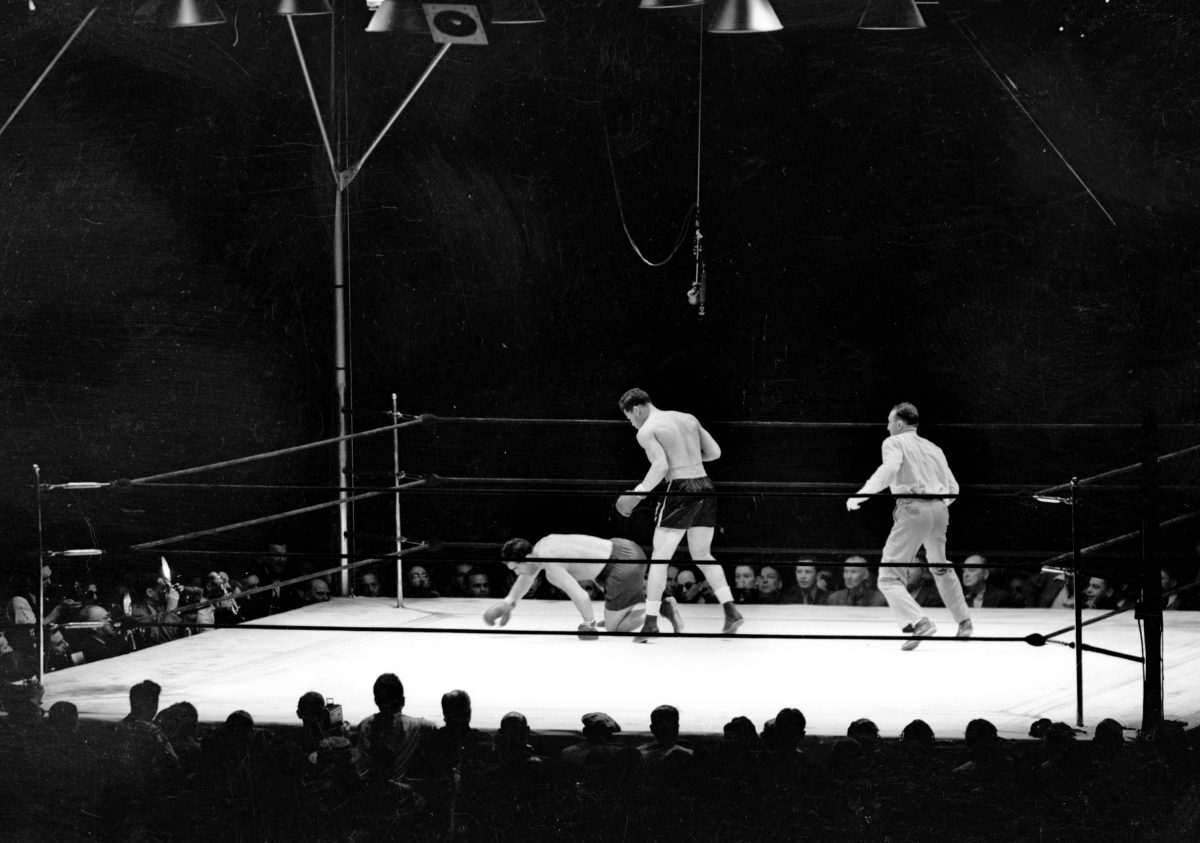

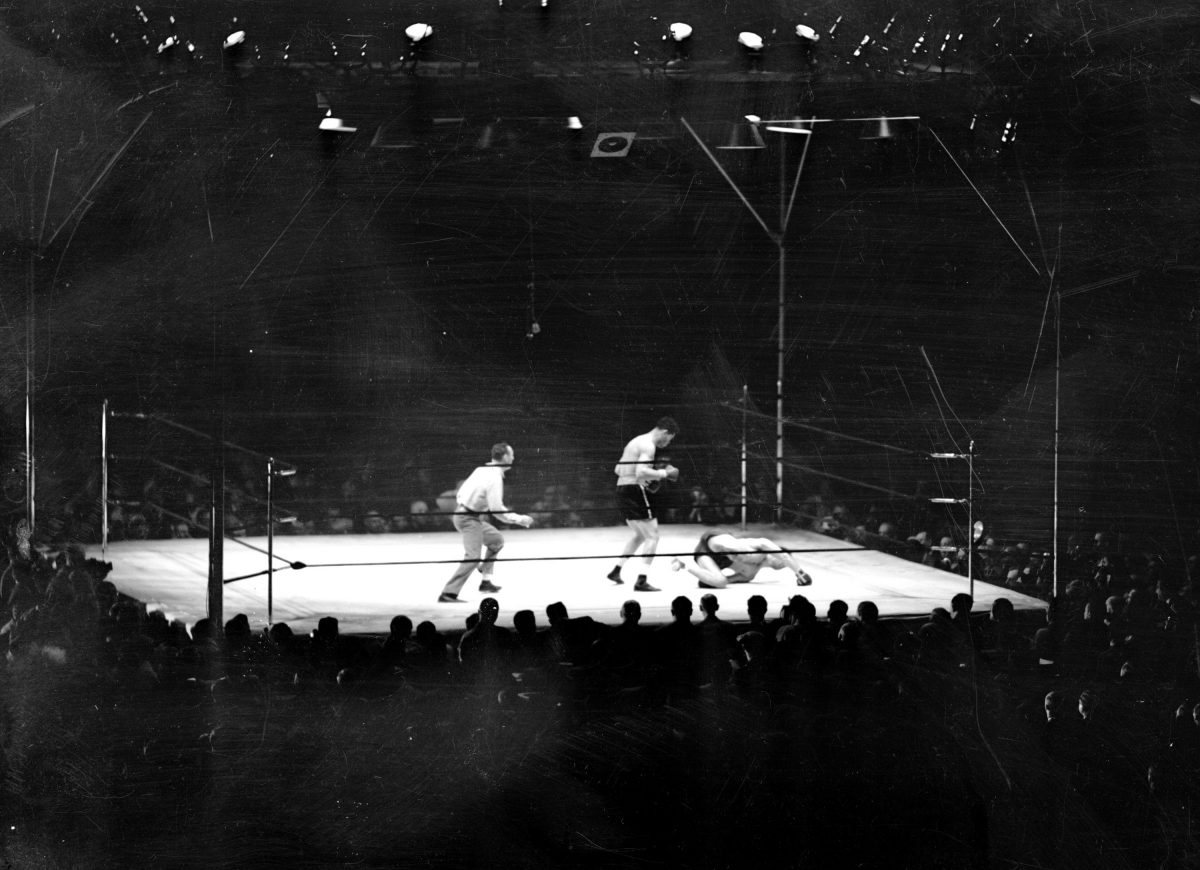

UNITED STATES – JUNE 22: Joe Louis vs Max Schmeling., Max spins as he plunges toward canvas. (Photo by NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

UNITED STATES – JUNE 22: Joe Louis vs Max Schmeling., Both hands on the canvas, Max tries to get his bearings. No dice. He was back in his native Germany as far as last night’s fight was concerned. Joe’s terrific punching was too much. (Photo by NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Two years later the rematch was an international sensation. When Schmeling walked into to the ring at Yankee Stadium on June 22, 1938 a hail of rubbish was thrown from the stands. Joe Louis came out blazing in the first round and the German couldn’t cope at all. He was twice knocked down before the fight had practically begun and the fight was stopped in the first round. Hitler and his cohorts were friends no more and Max Schmeling and his wife Ondra were ostracised by the Nazis from then on.

Schmeling retired after a few unsuccessful bouts and at the beginning of WWII he was drafted into the German Army and saw front-line combat as a paratrooper. At the end of the war the Allies cleared him of any real Nazi complicity and during the immediate post-war years Schmeling and his wife did their best to scrape by, turning to farming, a failed return to the ring as a boxer, and then a brief career as a boxing referee. And then a former New York boxing commissioner who had become a Coca Cola executive remembered Schmeling as a non-Nazi hero to the German people, and offered him the Coke franchise in Germany. Schmeling finally prospered, as a businessman.

In 1954 Max Schmeling was invited to referee a bout in Milwaukee in 1954 on the same trip he drove to Chicago and went to see Joe Louis at home. They renewed an acquaintance that lasted until Louis’ death in 1981. The two ex-boxers even both appeared on Joe Louis’s “This is Your Life,” TV show. When Louis died in 1981, by then a poor man, Schmeling contributed towards the cost of the funeral. He had long repudiated his Nazi past and it became known that he had helped two Jewish men escape the Nazis by bravely hiding them in his hotel room in 1938.

After fifty-four years of marriage, Anny Ondra died in 1987 with her husband dying eight years later in February 2005. It was just seven months from his hundredth birthday. “I had a happy marriage and a nice wife,” he would tell an interviewer before his death. “I accomplished everything you can. What more can you want?”

Despite his incredibly long life, in the end Max Schmeling is almost only remembered these days for the time in the Yankee Stadium when he entered the ring and it was all over in two minutes. As the Polish/Czech actress said to the Bishop. Sorry.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.