“The death penalty never once acted as a deterrent in all the jobs I carried out. And I have executed more people than anyone this century” – Albert Pierrepoint.

William Joyce, the man with the infamous nickname ‘Lord Haw-Haw’, is one of Britain’s best known traitors. He had a catchphrase as famous as any comedian’s, and had a facial disfigurement in the form of a terrible scar that marked him as a ‘treacherous villain’ as if the words themselves were tattooed across his forehead. Saying all that, many people have argued that he shouldn’t have been convicted of treason at all, let alone executed for the crime.

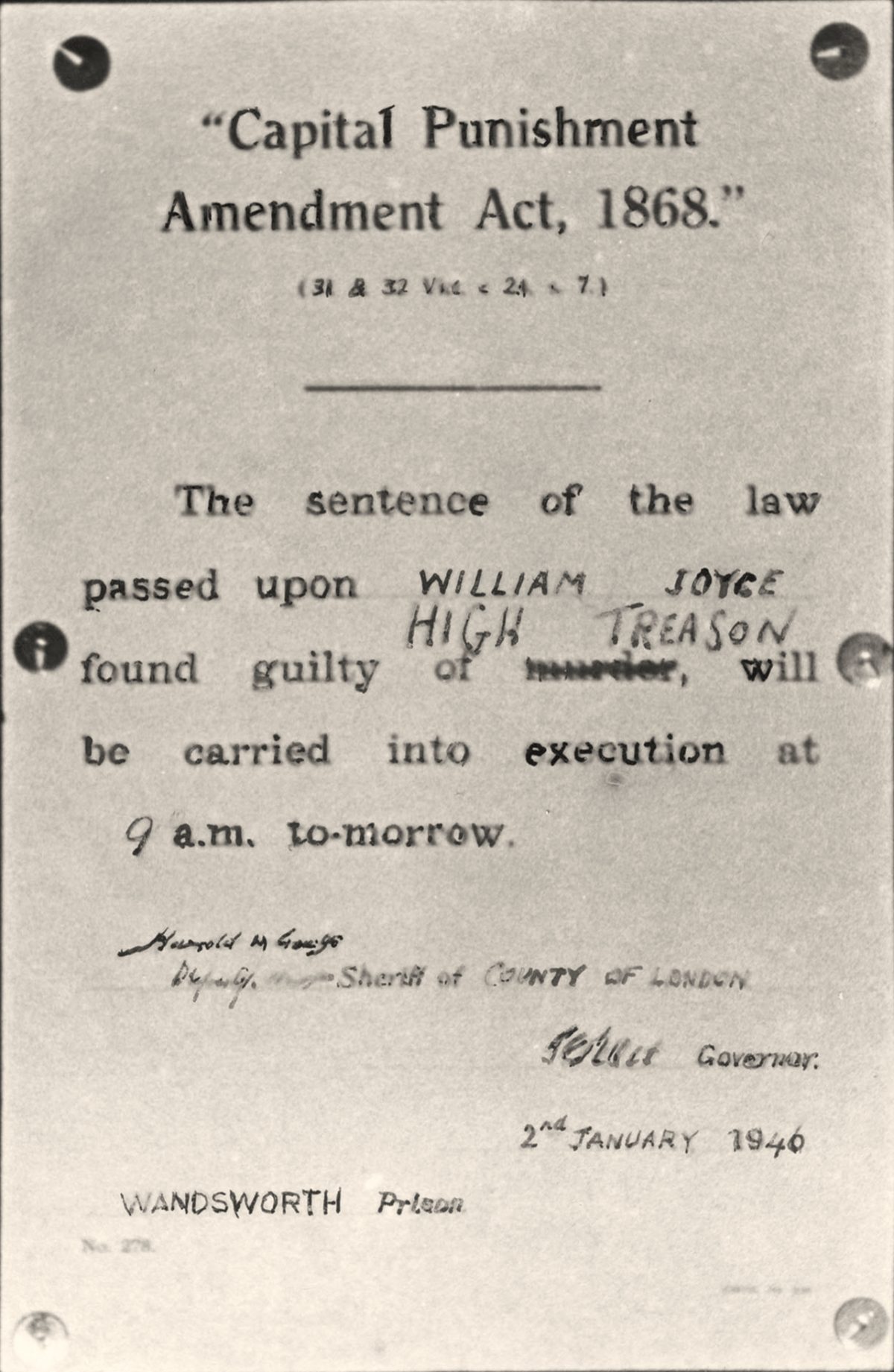

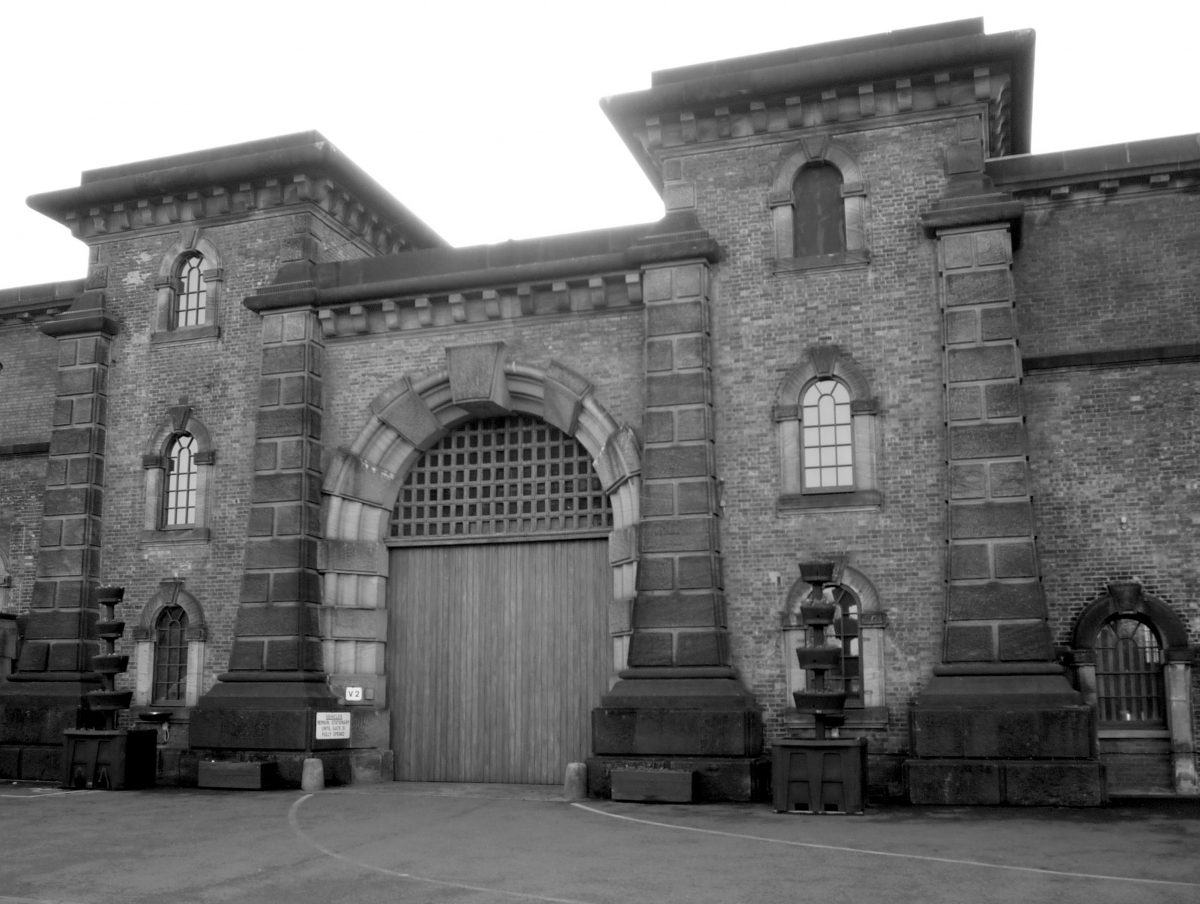

On the cold and damp morning of 3 January 1946, a large but orderly crowd had formed outside the grim Victorian prison in Wandsworth, the main gates of which aren’t more than a stone’s throw from the more salubrious surroundings of Wandsworth Common in south London. Some people had come to protest at what they considered an unjust conviction; others, albeit a handful, came to demonstrate about the use of capital punishment; while some, rather morbidly, wanted to be as close as they could to what came to be the last execution of a person convicted of high treason in Britain.

About 500 miles away, as the crow flies, at Joyce’s old school called St Ignatius, in Galway, a mass was taking place. The consecration of the Eucharist was timed for exactly the moment that Joyce was due to be executed. In the end the planned timing was in vain. It was at one minute to nine, an hour later than initially planned, when the governor of Wandsworth prison entered the condemned man’s cell to inform him that his time had come.

Group of junior students in four rows with their two teachers, Mr. O’ Shea and Mr. Scallon. Includes William Joyce (Lord Haw-Haw) in 1919

William Joyce had woken early that morning. He washed, but didn’t shave, and changed from his prison clothes into the blue serge suit he had been wearing at the time of his arrest in Germany. He refused any breakfast but he drank a cup of tea. For the last few months Joyce had actually been eating relatively well and while in prison his weight had increased substantially. When he was first brought to Wandsworth in the autumn he weighed 135 pounds (61 kg) but was now 151 pounds (68.5 kg). This wasn’t incidental information at the time; the weight gain was of more than passing interest to Albert Pierrepoint, the man who was to be his executioner.

The weight of every prisoner for whose death he would be ultimately responsible, he carefully noted in a leather-covered diary or ledger. It carried the details of all the executions for which he had been responsible and contained the dates, ages, heights, weights and, most importantly, the ‘drop’ for each hanging. Part of the hangman’s craft was to calculate the exact length of rope required to instantly kill the condemned man or woman. If the rope was too long, the criminal would be decapitated; too short, and it would be an agonising death of several minutes by strangulation.

Pierrepoint’s calculations were worked out from grim advice given in an official 1913 government document called the Table of Drops. It had been put together after a series of failed hangings at the end of the nineteenth century, including those of John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee, also known, not surprisingly, as ‘the man they couldn’t hang’. Lee survived three attempts to hang him at Exeter Prison in 1885 after which the Home Secretary commuted his death sentence. He was released twenty-two years later in 1905 and died in the USA in 1945. A committee, chaired by Lord Aberdare, was formed in 1886 to discover and report on the most effective manner of hanging, the results of which were published three years later. After a few more unfortunate incidents, a significantly revised edition of the Table of Drops was published in 1913.

Hangman Albert Pierrepoint left seen here at Euston Station traveling home by train after the execution of Ruth Ellis

In 1917, as a twelve-year-old, and twenty-eight years before he came face to face with William Joyce in the cell at Wandsworth, Albert Pierrepoint had been asked at school to compose an essay about his future ambitions. He wrote: ‘I would like to be public executioner as my Dad is, because it needs a steady man who is good with his hands like my Dad and my Uncle Tom and I shall be the same.’ Young Albert had only found out about his father’s macabre profession the year before, although he didn’t know that, after carrying out 107 executions, he had been dismissed from his post seven years previously after arriving drunk at Chelmsford prison to carry out a hanging. Albert’s Uncle Tom, however, went on to work as a hangman for thirty-seven years before his eventual retirement in 1946 after a dispute over compensation for a cancelled hanging.

In 1931 Albert wrote to the prison commissioners offering his services as an assistant executioner. A few months later, after initially being told that there were no vacancies, he was offered an interview at Strangeways prison in Manchester. After a week-long course at Pentonville prison, Pierrepoint’s name was added to the List of Assistant Executioners on 26 September 1932. Pierrepoint’s first execution as ‘Number One’ was of the ex-nightclub owner and gangster Antonio ‘Babe’ Mancini, at Pentonville on 17 October 1941. Just before the trapdoor was sprung Mancini was heard to utter a muffled ‘Cheerio!’ Mancini was to be the first of many and Albert Pierrepoint, who took pride in making death by hanging ‘as instant and humane a thing as it could ever be’, went on to hang 433 men and seventeen women during his lifetime.

Albert Pierrepoint the offical executioner of England seen here on honeymoon with his wife . September 1952

Thirteen months older than Albert Pierrepoint, William Joyce had been born in Brooklyn, New York, in April 1906 to an English Protestant mother and an Irish Catholic father. His father had already taken United States citizenship when, three years after the birth, the family returned to Galway, where William went on to attend the St Ignatius Jesuit College from 1915 to 1921.William was precociously politically aware and, like many Irish people at the time, was politicised by the Irish War of Independence. Unlike most in Galway, however, he and his father were Unionists and both openly supported British rule. William hung around the headquarters of the Royal Irish Constabulary at Lenaboy Castle, and later said that he had aided and run with the infamous Black and Tans, the notoriously undisciplined and brutal British auxiliary force sent to Ireland after the First World War in an attempt to help put down Irish nationalism. William essentially hated anyone who held anti-British views, and he was not yet sixteen when he was forced to escape to London after several death threats from the local IRA.

After a short stint in the British Army (he was soon discharged when it was found he had lied about his age), Joyce enrolled at Birkbeck College of the University of London, where he gained a first but also developed an initial interest in Fascism. In 1924, while stewarding at a Conservative Party meeting at the Lambeth Baths in Battersea, a seventeen-year-old Joyce was attacked by a gang in an adjacent alleyway, and received a vicious and deep cut from a razor that sliced across his right cheek from behind the earlobe all the way to the corner of his mouth. He lost a lot of blood and initially his life was in danger, but after two weeks he was released from hospital. It left him with a terrible facial scar. Joyce was convinced that his attackers were ‘Jewish communists’ and the incident influenced the rest of his life.

(c) Pictures by Mike Gunnill: William Joyce far right, sitting. Shortly after joining the British Union of Fascists in 1932. Leader Oswald Mosley, third left from Joyce.

In 1933, at the age of twenty-seven, Joyce joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. Within a couple of years he was promoted to the BUF’s director of propaganda and was responsible for training speakers. He was a gifted orator and was soon deputising for Mosley at major rallies. Once a female heckler shouted, ‘You’re a right bastard,’ to which he replied, ‘Thank you, mother.’ For a while Joyce was the star of the British fascist movement.

William Joyce was instrumental in moving the union towards overt anti-Semitism, something with which Mosley had initially been relatively uncomfortable. Joyce’s career with the BUF only lasted five years, however, for in 1937, with membership plummeting, a devastated Joyce was sacked from his paid position in the party by Mosley.

(c) Pictures by Mike Gunnill: William Joyce & second wife Margaret in Shoreditch Market shortly before fleeing the United Kingdom for Germany and the start of WW2.

In late August 1939, shortly before war was declared, and probably tipped off by a friend in MI5 that he was about to be arrested, Joyce and his wife Margaret fled to Germany. There he struggled to find employment until he met one of his English supporters, the Mosleyite Mrs Frances ‘Dorothy’ Eckersley, who soon got him recruited for radio announcements and script writing at German radio’s English service in Berlin. Crucially, this was at a time when his British passport was still valid. Four years previously the American-born Joyce had, under false pretences, obtained a British passport so that he could accompany Mosley abroad. At the time, a birth certificate was not needed to substantiate statements made on application; an endorsement from a public official was all that was required.

The infamous nickname of ‘Lord Haw-Haw’, associated with William Joyce to this day, was coined by a Daily Express journalist called Jonah Barrington not two weeks into the war. The title was actually meant for someone else completely – almost certainly a man called Norman Baillie- Stewart who had been broadcasting in Germany from just before the war. Barrington’s nickname referenced Baillie-Stewart’s exaggeratedly aristocratic way of speaking: ‘A gent I’d like to meet is moaning periodically from Zeesen [the site near Berlin of the English short-wave transmitter]. He speaks English of the haw-haw, dammit-get-out-of-my- way variety, and his strong suit is gentlemanly indignation.’

Four days later, on 18 September, Barrington started to call the broadcaster from Germany ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ and wrote in the Express: ‘Lord Haw-Haw, hard though he pretends to be blue-blooded and British, trips up occasionally, “Sir Winston Churchill,” he said recently, and then, “Ach, nein! I mean Mr Winston Churchill.”’ Barrington also tried to imagine Lord Haw-Haw’s appearance: ‘From his accent and personality I imagine him with a receding chin, a questing nose, thin, yellow hair brushed back, a monocle, a vacant eye, a gardenia in his buttonhole. Rather like P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster.’

Baillie-Stewart had already been convicted in the United Kingdom for selling military secrets to Germany in the early thirties, and had the dubious distinction of being the last person in a particularly long line to have been imprisoned for treason in the Tower of London. Late in 1939, when William Joyce had become the more prominent of the Nazi propaganda broadcasters (although at the time no one knew exactly who he was), Barrington swapped the title over and, in April 1941, he announced Lord Haw-Haw’s real name. In Germany, Joyce’s nickname was ‘Froehlich’ which means ‘Joyful’.

The British public were officially discouraged from listening to the Lord Haw-Haw broadcasts which always began with the infamous words, ‘Germany calling, Germany calling.’ Just three months into the war, however, the News Chronicle reported that Lord Haw-Haw’s ‘Views on the News’ broadcasts were listened to by about 50 per cent of the British public. Cassandra’s popular column in the Daily Mirror thought the problem was with the BBC’s dreary output, saying that it was time to ‘get hold of a news-broadcaster with real incisive personality’:

The BBC has never seemed to be able to rid itself of the polite, charming and somewhat effeminate young men who nightly mince through the news. Haw-Haw has ten times the punch of any one of them … Are they still going to go on lisping their nightly way to defeat on the air. Or is somebody going to get a chance to get in front of the microphone and put over our point of view in accents slightly less reminiscent of well-bred motor salesmen down on their luck.

Lord Haw-Haw’s over-the-top and sneering attacks on the British establishment were enjoyed by many, and early in 1940 the Daily Expresswrote: ‘More and more people are tuning in to Nazi broadcasting and laughing their heads off at the preposterous bedtime stories of Lord Haw- Haw.’ It wasn’t only because the broadcasts were funny that the British public were tuning in: during an era of heavy state censorship and restricted information there was a natural desire by listeners to hear anything Nazi Germany was saying, whatever was said. At the start of the war, simply because there was more to brag about, the German news reports were considered, by some people, to contain slightly more truth than those of the BBC. It was never taken too seriously though, and William Joyce’s manner didn’t help. The Daily Express again: ‘Enemy propaganda is taken at its face value by the British people. Our Government has relied upon British common-sense, with the result that the very incredibility of enemy lying destroys its effectiveness. That’s comforting.’

Lord Haw-Haw takes his constitutional in the Tiergarten, Berlin

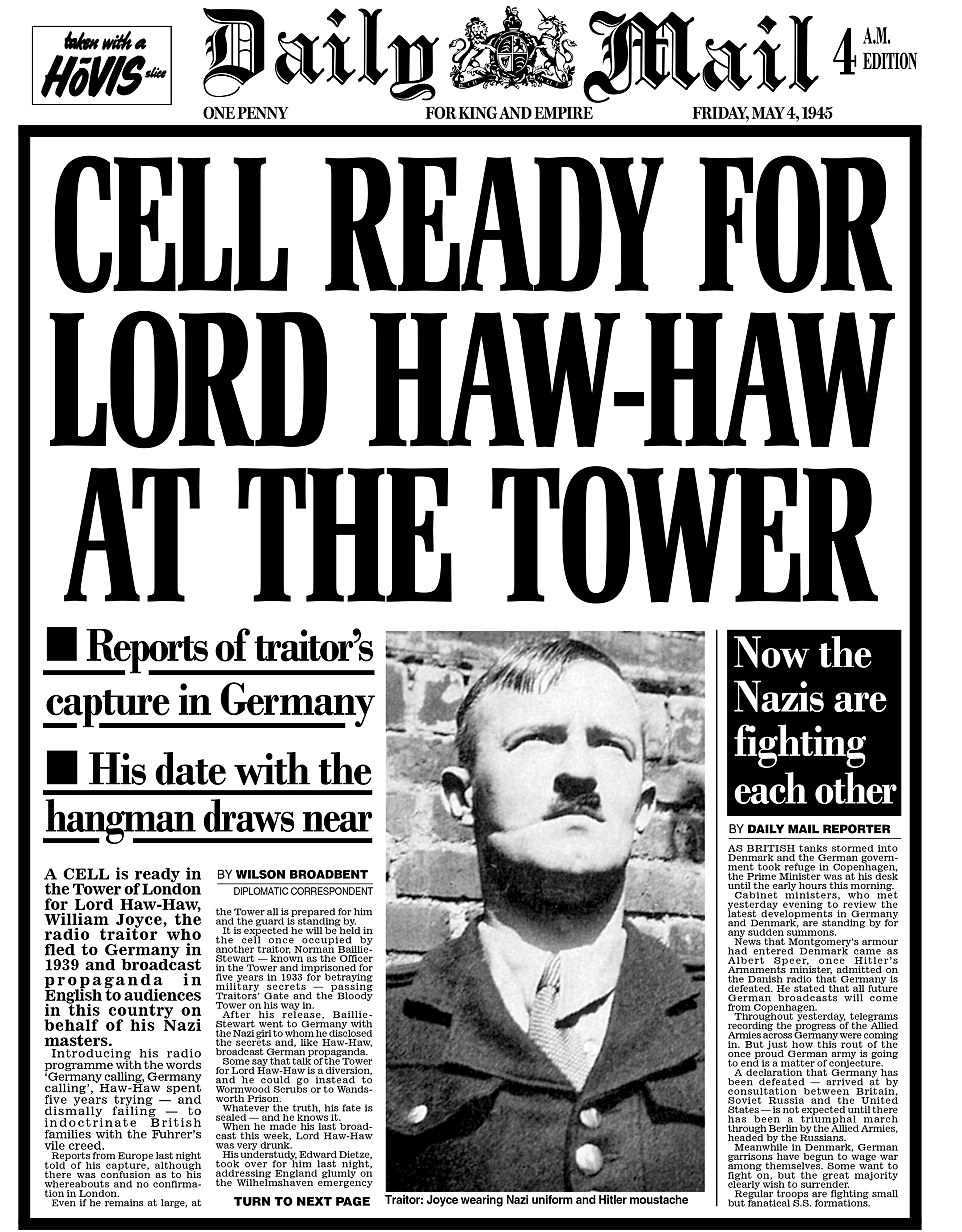

As the tide turned towards the Allies in the latter stages of the war, Joyce and his wife moved to Hamburg. On 22 April 1945 he wrote in his diary: ‘Has it all been worthwhile? I think not. National Socialism is a fine cause, but most of the Germans, not all, are bloody fools.’7 Eight days later, and on the very day that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide in their Berlin bunker, Joyce made his last broadcast. He was drunk, and the remains of his Irish accent were heard through his slurring voice. He finished his final broadcast with, ‘Heil Hitler! And farewell.’ William and his wife Margaret soon fled to Flensburg, a town near the Danish border, and it was there, in a nearby wood, that Joyce was captured by two soldiers. They, like Joyce, were out looking for firewood and when the former Lord Haw-Haw with his distinctive voice stopped to say hello, one of the soldiers asked, ‘You wouldn’t by any chance be William Joyce, would you?’ To ‘prove’ otherwise, Joyce reached for his false passport and one of the soldiers, thinking he was reaching for a gun, shot him through the buttocks, leaving four wounds.

The soldier who had shot Lord Haw-Haw’s bottom was called Geoffrey Perry. He had, however, been born into a German Jewish family as Hourst Pinschewer and had only arrived in England to escape from Hitler’s persecution. In the end a German Jew, who had become English, had arrested an Irish-American, who pretended to be English but had become German. It was almost poetic justice.

William Joyce at the time of his arrest in 1945.

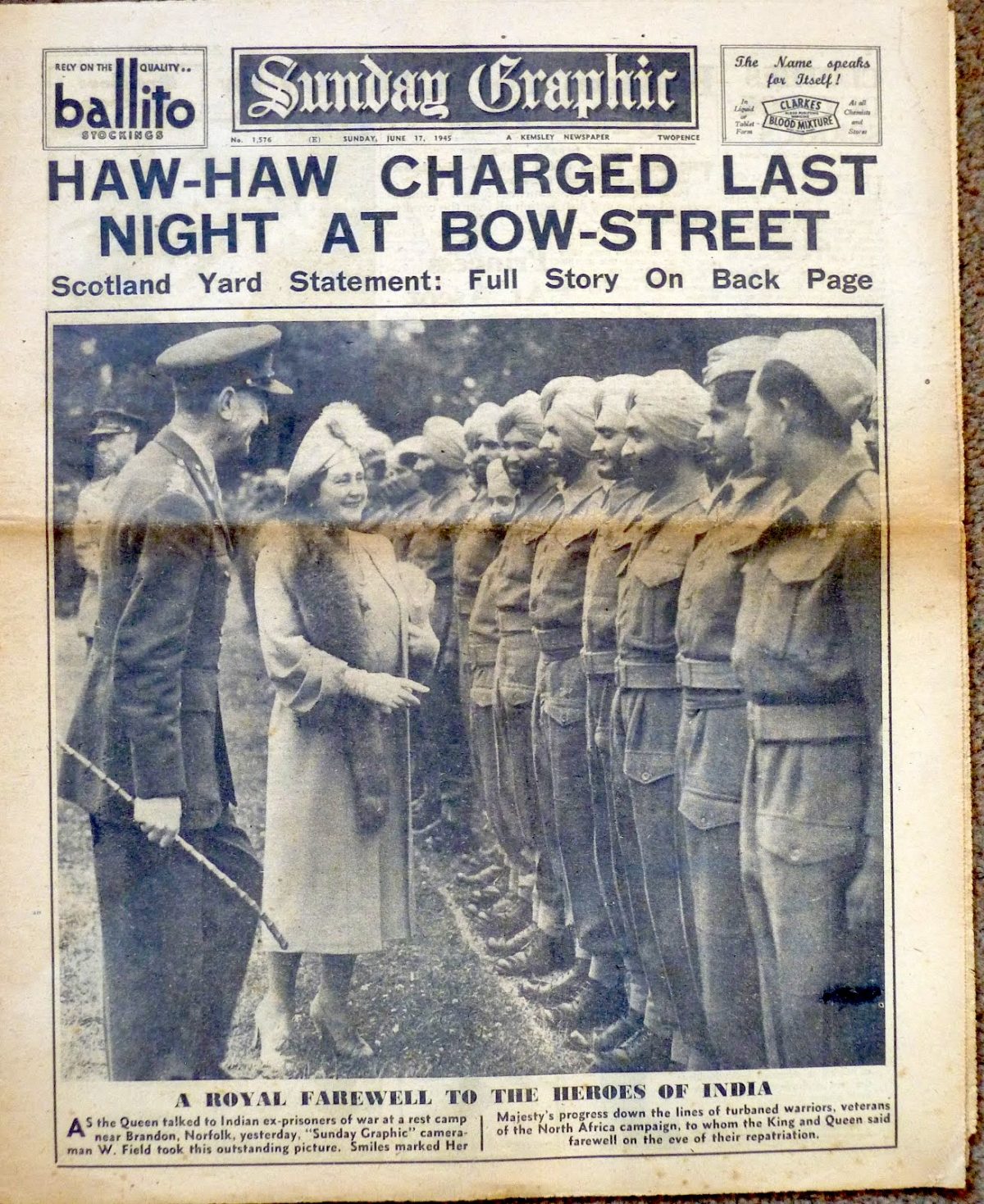

Sunday Graphic Lord Haw-Haw charged at Bow Street

Back in London, Joyce was charged at Bow Street magistrates’ court and in the dock quietly stated, ‘I have heard the charge and take cognisance of it.’ He was then driven to Brixton prison in a Black Maria and on arrival it is said that he mumbled, ‘So this is Brixton.’ ‘Yes,’ retorted his guard, ‘not Belsen.’ The American writer, journalist and historian William L. Shirer met Joyce in Berlin during the early part of the war and said what he thought had driven him: ‘I should say that he has two complexes which have landed him in his present notorious position. He has a titanic hatred for Jews and an equally titanic one for capitalists. These two hatreds have been the mainsprings of his adult life.’

The trial of William Joyce began on 17 September 1945 and for a short period, when his American nationality came to light, it seemed that he might be acquitted. ‘How could anyone be convicted of betraying a country that wasn’t his own?’ his defence lawyers argued. The attorney- general, Sir Hartley Shawcross, however, successfully argued that Joyce’s possession of a British passport (even if he had misrepresented himself to get it) entitled him to diplomatic protection in Germany and therefore he owed allegiance to the king at the time he started working for the Germans.

There was a problem, however: the BBC monitoring service could not identify any of his broadcasts before 2 August 1940, and the only evidence came from Detective Inspector Albert Hunt of the Special Branch who had questioned Joyce before the war while he was an active member of the BUF, and who claimed to have recognised his voice while monitoring broadcasts in the autumn of 1939. He couldn’t say which station he had been listening to, nor the country from which it came. He couldn’t even say whether it was September or early October 1939 when he thought he had heard Joyce’s voice.

Until 1945 Inspector Hunt’s less than impressive evidence would not have been enough to convict anyone for the grave crime of treason. The Treason Act of 1697, which itself amended the Statute of Treasons of 1351, required either two acts of treason witnessed by one person, or one overt act witnessed by two people. Under these ancient provisions, Joyce would have been acquitted. In June 1945 a new treason act was passed which abolished the special rules of evidence and replaced them with the same rules that were applicable to murder trials. Joyce was kept in Germany until this new act was law, and then brought to Britain the next day to be charged.

On 19 September 1945, almost exactly six years after he had started broadcasting from Germany, William Joyce stood in the dock of the Old Bailey. The judge, in his summing up, quoted a law from 1707 that said the physical presence of a man in the country was not essential to the allegiance he owed to the king. In the end the jury took less than twenty minutes to return with a verdict. The Manchester Guardian reported that ‘Joyce’s nervous twitch twisted into something like a smile’ when he heard Mr Justice Tucker pronounce the sentence of death upon him for treason by broadcasting propaganda for the king’s enemies. Convicted by virtue of Inspector Hunt’s uncorroborated evidence, Joyce, albeit unsuccessfully, appealed to the Court of Criminal Appeal and the House of Lords.

A sizeable minority of the population was uncomfortable with the verdict, mainly because of the nationality issue, but also because he was generally seen as not much more than a figure of fun. On Christmas Day 1945 an accountant named Edgar Bray wrote to King George VI: ‘I know nothing about Joyce, and nothing about his Politics. I don’t know much about Law either, but I do know enough to be firmly convinced that we are proposing to hang Joyce for the crime of pretending to be an Englishman which crime, so far as I am aware, in no possible case carries a Capital penalty. It happens to be just our bad luck, that Joyce actually WAS an American, (and now IS a German subject), but that is no reason to hang him, because we are annoyed at our bad luck.’ The historian A. J. P. Taylor agreed with Mr Bray and once made the point that Joyce was essentially hanged for making a false statement on a passport, the usual penalty for which was the trivial and insignificant fine of just £2.

A notice board for the execution of William Joyce outside Wandsworth Prison on the eve of his execution for treason January 1946

Fifteen weeks after the Old Bailey trial, the governor of Wandsworth prison, accompanied by Albert Pierrepont and his assistant Alexander Reilly, entered William Joyce’s cell. From that point on everything moved so quickly that Joyce would have hardly known what was happening. Pierrepoint was particularly proud of the speed of his executions and they rarely took more than a few seconds after a prisoner had set eyes on him. Pierrepoint had a macabre party piece which he demonstrated to anyone new assisting him during an execution. Before leaving his room to hang anyone, he would sometimes light a cigar and then leave it burning in an ashtray. When he returned to the room after the hanging, he would draw on the cigar and show that it was still alight.

Almost as soon as the three men entered Joyce’s cell, Pierrepoint placed a pinioning belt around Joyce’s wrists behind his back and then pulled it tight. At the same time a false wall was drawn back and Joyce was led to the adjacent execution chamber a few yards away. With just enough time before they reached the chalked marks on the varnished wood floor, Joyce looked down at his badly trembling knees and smiled. It was noticed by the practised and experienced hangman, who calmly uttered the last words that Joyce ever heard: ‘I think we’d better have this on, you know.’ While he was speaking he placed a white cap over Joyce’s head and subsequently the noose straight after. Pierrepoint heard a familiar click of the belt and buckle as Reilly quickly pinioned Joyce’s legs. As soon as this was completed the assistant stood up and flung his arms back in a gesture of completion. At that point Pierrepoint pulled the lever which automatically opened the trap door beneath Joyce’s feet. The prisoner’s spinal cord was ripped apart between the second and third vertebrae and the man known throughout the country as Lord Haw-Haw was dead.

Not far away a group of smartly dressed men in winter coats stepped away from the main crowd that was waiting outside the Wandsworth prison gates and, behind some nearby bushes, almost surreptitiously, raised their right arms in the ‘Heil Hitler!’ salute. Within a few minutes of Albert Pierrepoint’s expert execution, and with the blood from Joyce’s scar that had burst open during the hanging still dripping onto a spreading red stain on the canvas floor, the body was taken to the prison mortuary. The jury that had convicted him was allowed to see the remains and a coroner pronounced that the death was due to ‘injury to the brain and spinal cord, consequent upon judicial hanging’.

Wandsworth Prison gates

At eight minutes past nine a prison officer came out and pinned on to the prison gates an official announcement that William Joyce had been hanged. At 1 p.m. the BBC Home Service reported the execution and read out the last, unrepentant pronouncement from the now-dead man:

In death, as in this life, I defy the Jews who caused this last war, and I defy the power of darkness which they represent. I warn the British people against the crushing imperialism of the Soviet Union. May Britain be great once again and in the hour of the greatest danger in the west may the Swastika be raised from the dust, crowned with the historic words, “You have conquered nevertheless.” I am proud to die for my ideals; and I am sorry for the sons of Britain who have died without knowing why.

There were very specific rules applicable to the burial of executed prisoners at the time, and William Joyce’s body was treated the same as any other. He was buried within the Wandsworth prison walls, in an unmarked grave, and was allowed no mourners. In the middle of the night, the body had been dumped, literally unceremoniously, on top of the remains of another man, a murderer called Robert Blaine who had been hanged five days previously. A layer of charcoal, not lime, was used to separate the two bodies.

In total 135 people were hanged at Wandsworth prison during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the final execution taking place when Henryk Niemasz was hanged on 8 September 1961 for the murder of Mr and Mrs Buxton in Brixton. The gallows were not dismantled until 1993, which was twenty-nine years after the last execution in Britain, and twenty-four years after the death penalty was abolished for murder, although the death penalty still existed for treason until 1998. The condemned cell is now used as a television room for prison officers.

Wandsworth prison was not to be the final resting place for William Joyce. His daughter had long thought that he should be buried in a cemetery and not in an unmarked grave in a south London prison yard. After a long campaign and several letters to various home secretaries, she was at last allowed to have her father’s body properly buried. On 18 August 1976 the original grave was dug up in the middle of the night and the remains were reburied in the Protestant part of the large Bohermore cemetery in Galway. ‘Ireland calling! Ireland calling!’ said the Guardian and ‘Lord Haw-Haw goes home’ wrote the Daily Mail. Joyce, even thirty years after his execution, had few supporters, whether Irish or British, and the grave was placed in the cemetery some distance from any others. Whether it is because William Joyce has been forgotten or the space at Bohermore is now more of a premium but it is only in the last few years that Joyce’s grave has been joined by any others.

William Joyce’s Grave at Bohermore Cemetery Galway.

This is an extract from the acclaimed book Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics by Rob Baker and available from Amazon and other good book shops.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.