“I buried my negatives in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy. I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry, I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom”

– Henryk Ross (1950s, Israel) recalls his work as a news and sports photographer in the Lodz ghetto.

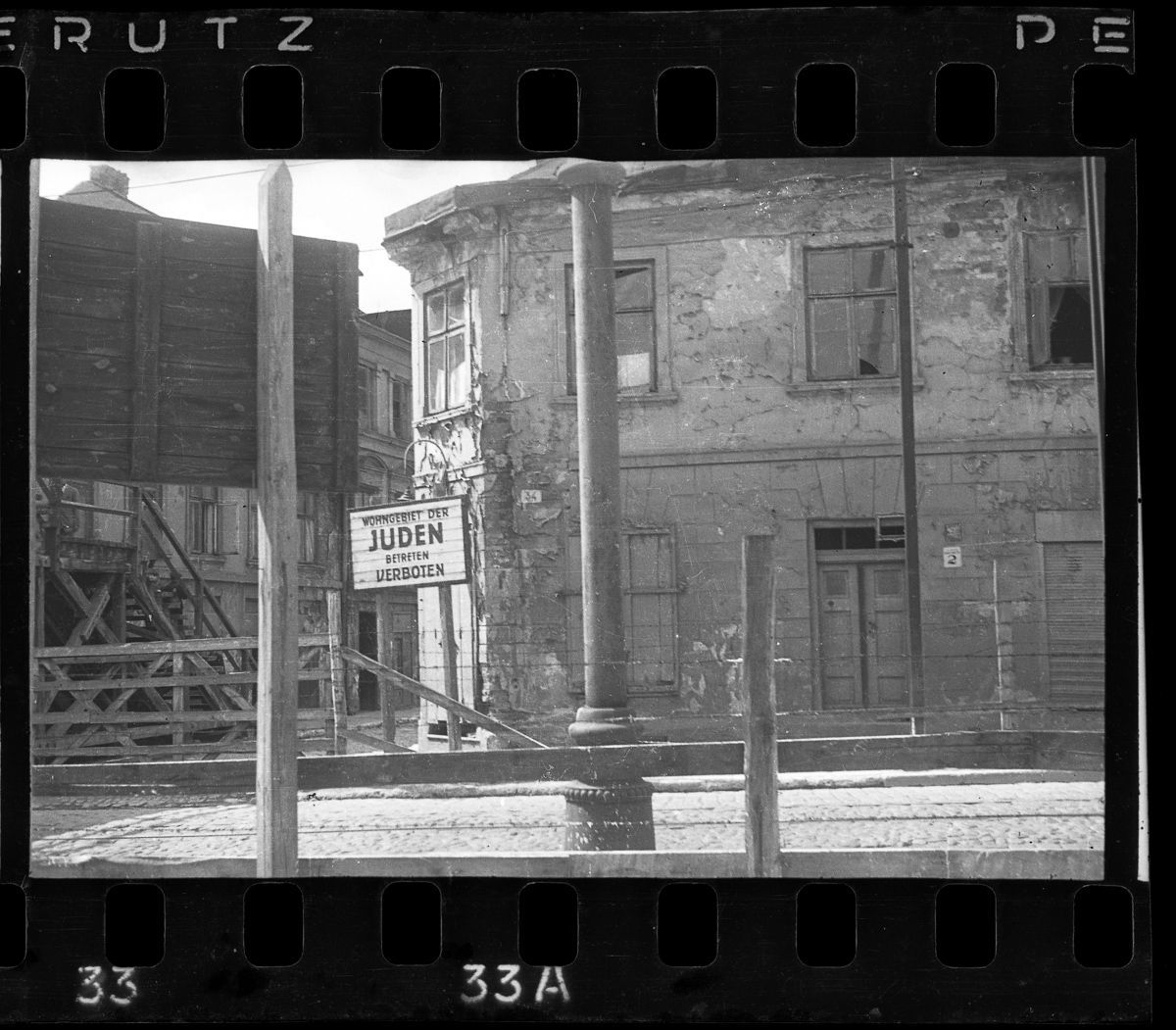

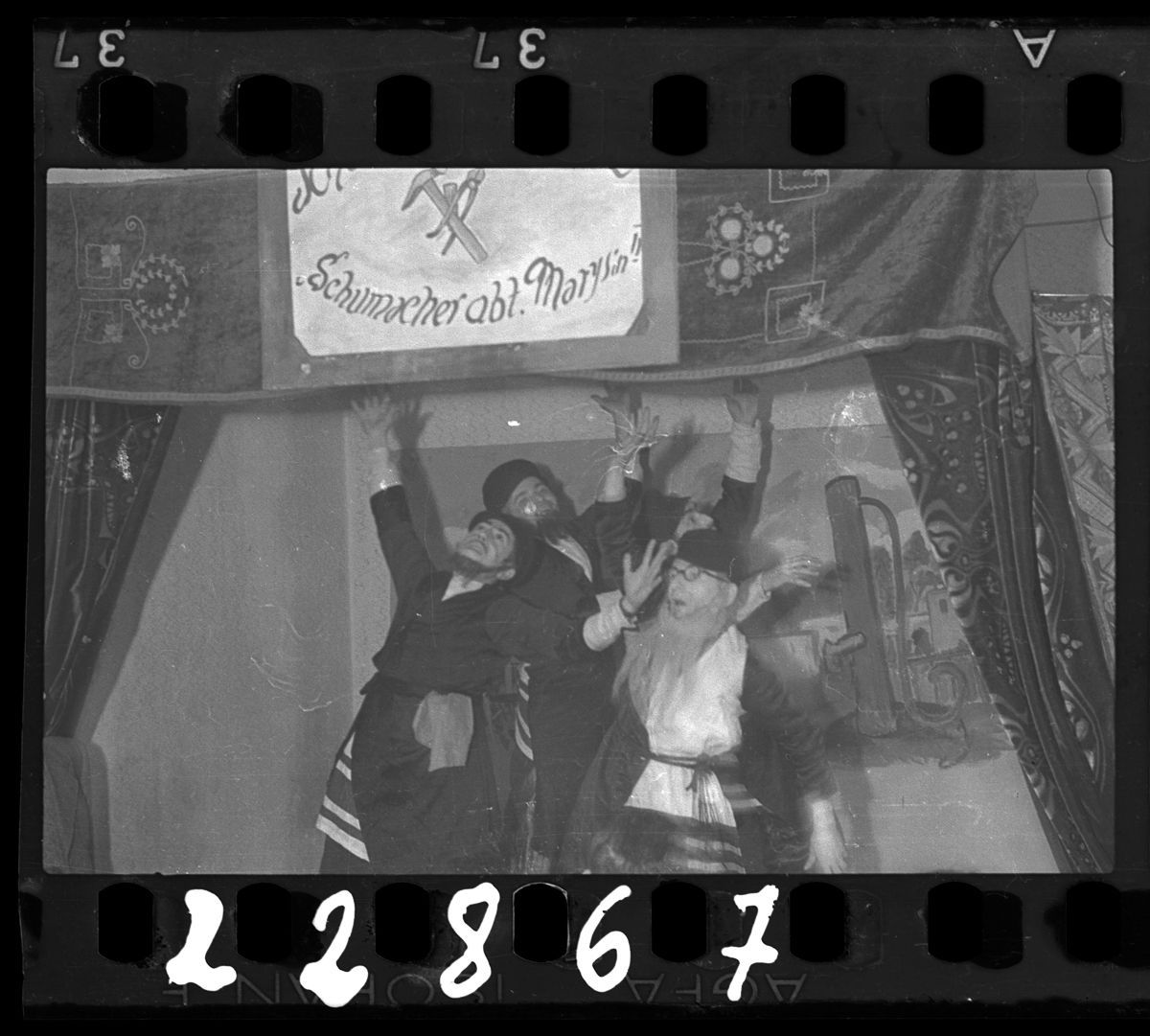

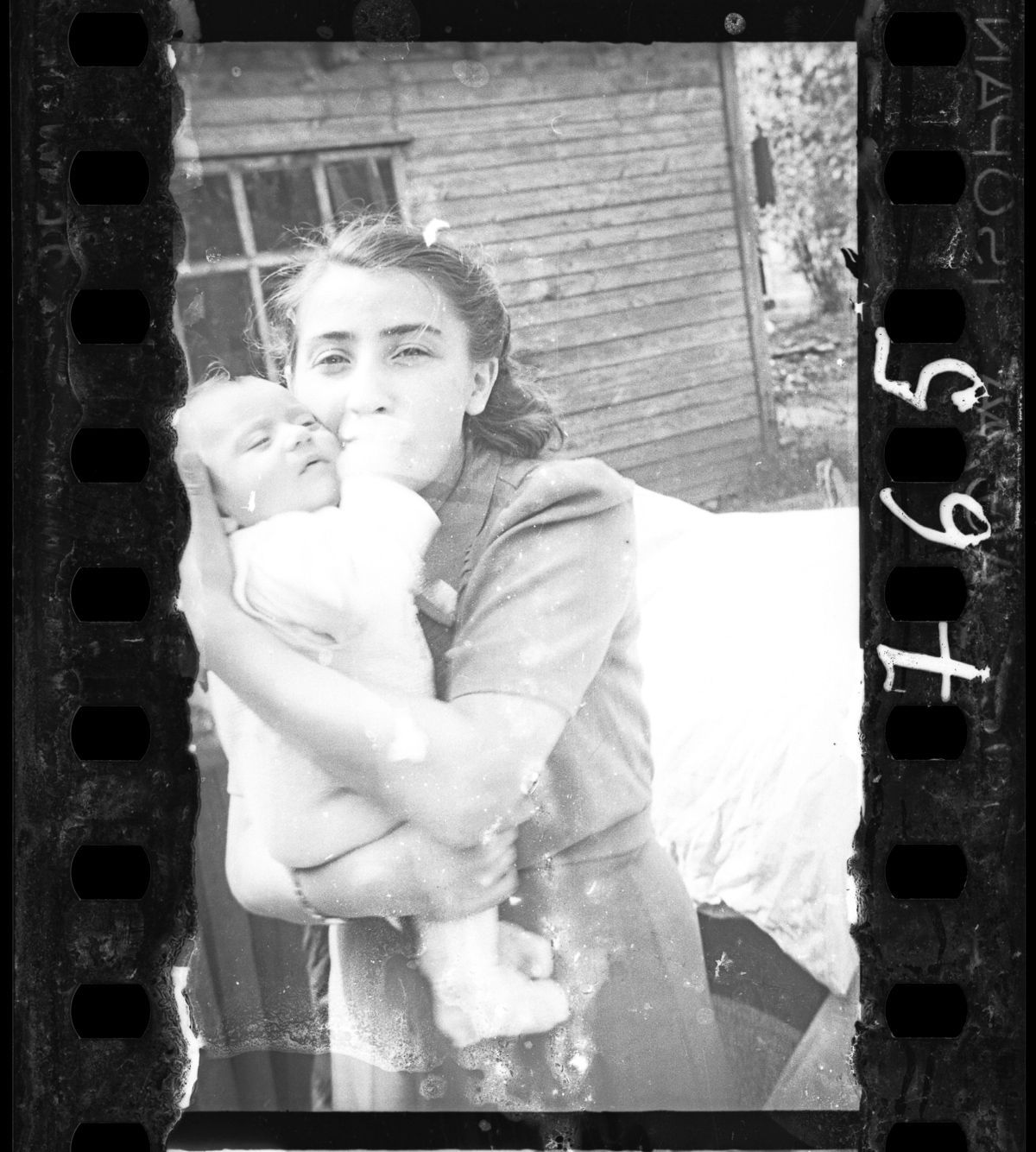

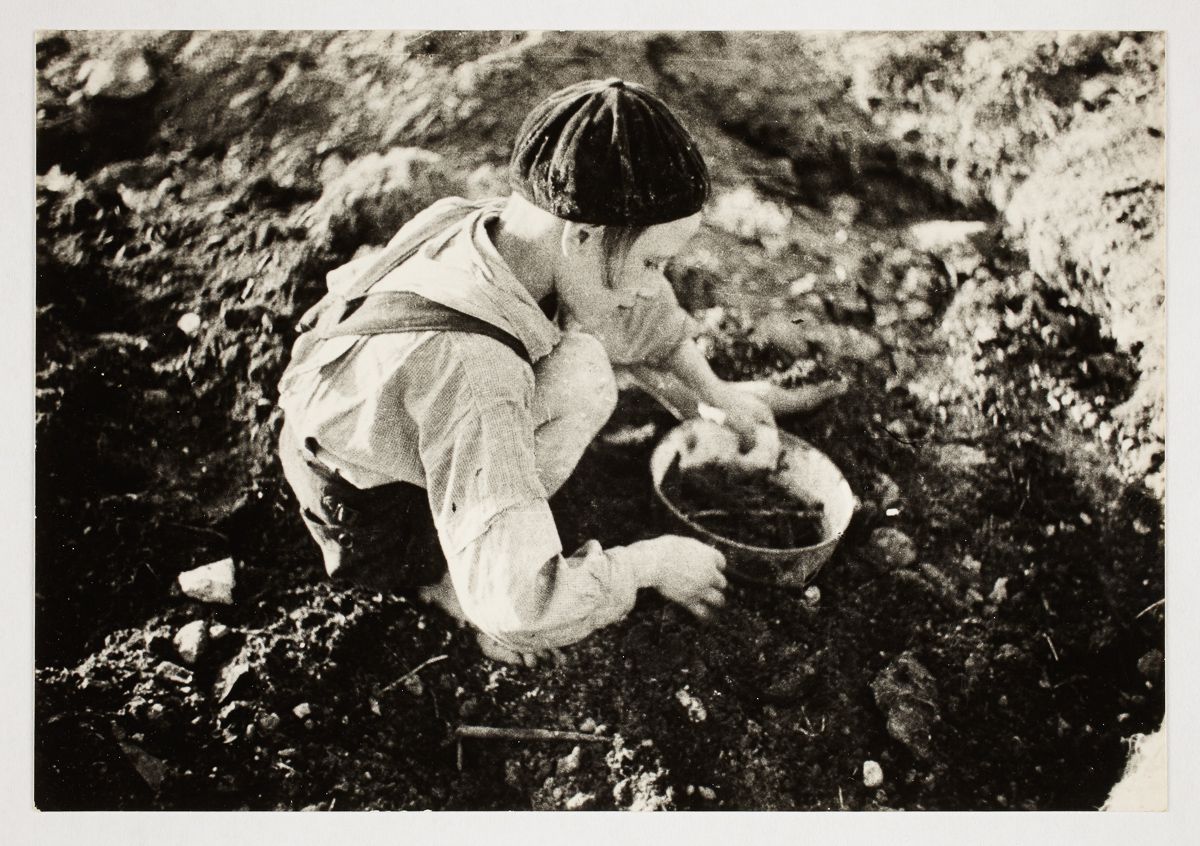

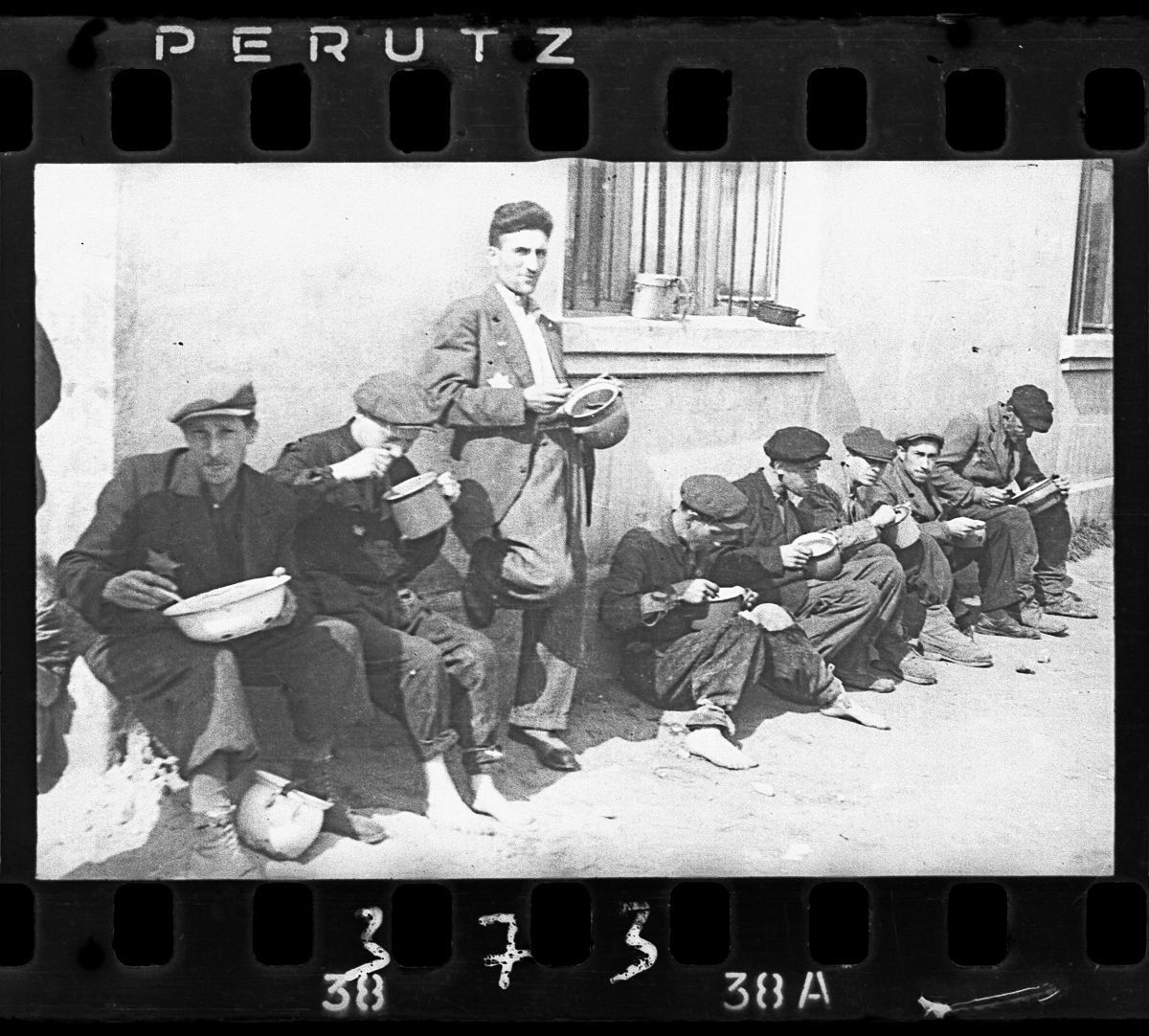

Employed by the Department of Statistics to record Jews working as slaves for the German Army in the Lodz ghetto, Henryk Ross would also capture the every day images of human life enduring forced labour and life under a death sentence in a part of the Polish city surrounded by armed guards and barbed wire . As well as recording scenes of depravation, abuse, disease and murder, Ross also recorded Jews at home before they were despatched to the death camps at Chelmno nad Nerem and Auschwitz.

In late 1944, people trapped in the Lodz Ghetto were in line to be slaughtered. Fearing his life coming to its end, Ross placed 6,000 negatives in a tar-lined box and buried them near his home. One day he hoped someone would find them and tell the world what had happened. One day when all the Jews were gone, someone would remember.

On Jan. 19, 1945, the Red Army rode into Lodz. Just 877 Jews were there to see them. There had been more than 233,000 Jews in Lodz when the Germans came. “The establishment of the ghetto is only a transitional measure,” wrote Friedrich Übelhör, German governor of the Kalisz-Lodz district, on December 10, 1939. “I reserve for myself the decision as to when and how the city of Lodz will be cleansed of Jews. The final aim must be to burn out entirely this pestilential boil.” The Soviets arrived too late for so many. The last train to the Nazi death camps left Lodz on 29 August 1944.

Henryk Ross was one of the survivors. Two months later Ross journeyed to his home on Jagielonska Street and dug for his treasure. Many negatives has been badly damaged. But many had not.

Renee Salt was sent to Lodz in 1942, aged 13, from another ghetto in her Polish hometown of Zdunska Wola, with her parents and an aunt.

Her younger sister had already been taken away by the Gestapo.

“The overcrowding, starvation and disease were just appalling. People were dying in the streets,” she told BBC News Online.

“We came with nothing – we didn’t have a piece of underwear to change into. The day we arrived we were starving and my mother gave something to a shopkeeper for a piece of cabbage. We were so hungry we could have swallowed wood…

“We got up at 0630 every morning at the latest. You had a drink if you could boil the water, ate, perhaps, if you had crumbs of bread, and worked all day long. We worked hard on starvation rations.

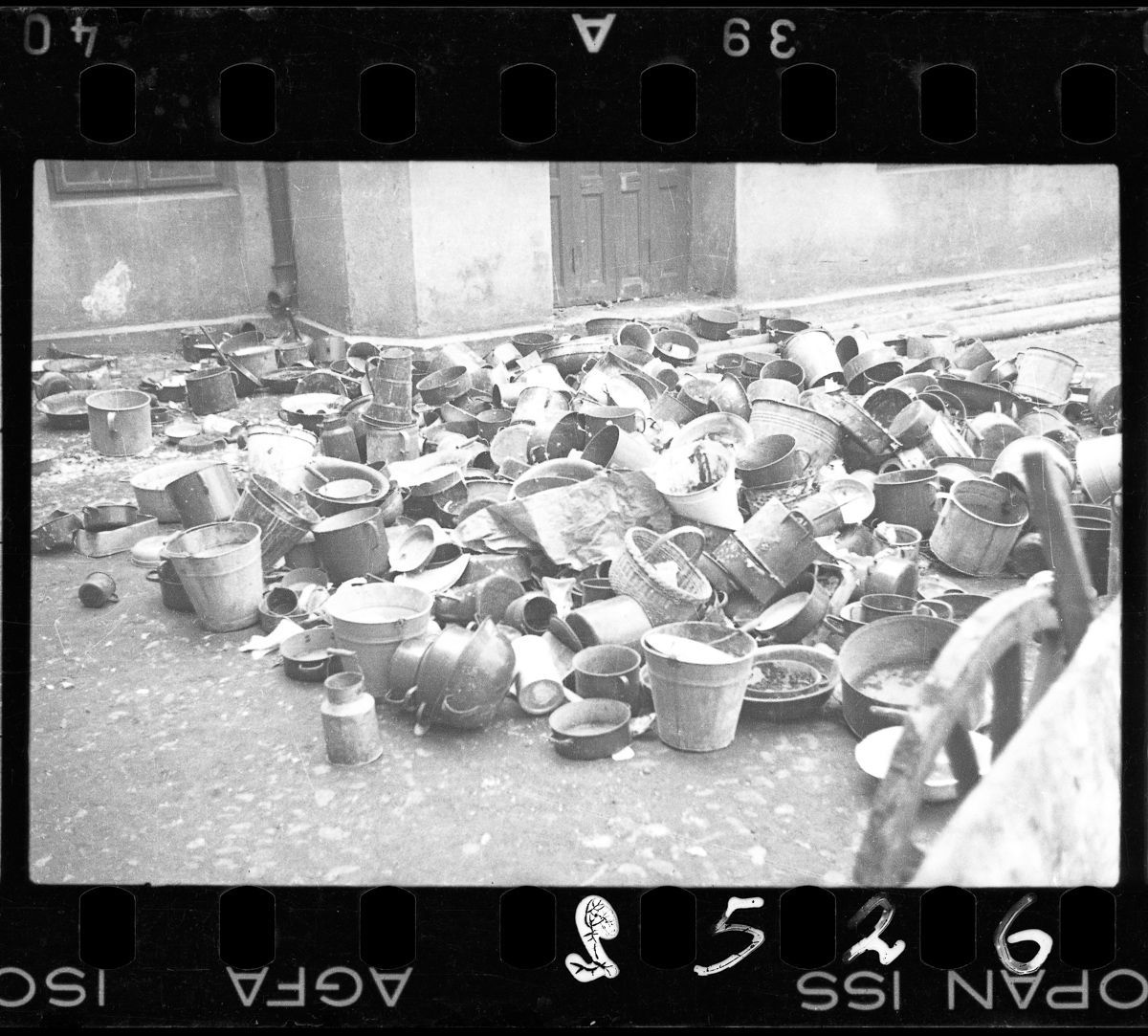

“We had no running water, no sanitation, no toilet. There was always a bucket outside. Life was very, very difficult. If you had a piece of cabbage, you didn’t have a piece of coal to cook it on. How can one describe conditions like that?” Mrs Salt said. “Looking back, you really can’t believe that you survived or that it happened, so how can others?

“The SS came to our places of work and brought everyone out to say the ghetto was being shut down,” Mrs Salt said. They promised us everything – good accommodation, good medical care, everything – as long as we came to the train station voluntarily.

“Soon the cleaners found notes in the cattle trucks saying people were being taken to concentration camps and killed. That was the first we heard of it. We couldn’t believe it.

“If we had known, I have no doubt that many people would have taken their own lives.”

1940

A man walking in winter in the ruins of the synagogue on Wolborska street (destroyed by Germans in 1939).

c. 1940-1944

A group of women with sacks and pails, walking past synagogue ruins heading for deportation.

1940

Henryk Ross photographing for identification cards, Jewish Administration, Department of Statistics.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.