The story of Russian Futurism began in Italy on February 20 1909, when millionaire poet F.T. Marinetti published his Futurist manifesto. Lawrence Pollard explains:

It was an early exercise in cultural branding. Marinetti took over the front page of newspapers across Europe and had his manifesto printed – a sort of advertorial for speed, youth, newness and the destruction of the old order. And he had set the template for the manifesto – shock tactics, declamation, bullet points, such as: “A racing car is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothace”, “Poetry must be a violent assault…” and “We glorify War…” It had 11 bullet points because 11 was his favourite number.

Marinetti declared.

FUTURISTIC MANIFESTO

1. We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of danger and of temerity.

2. The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, daring, and revolt.3. Literature having up to now magnified thoughtful immobility, ecstasy, and sleep, we want to exalt the aggressive gesture, the feverish insomnia, the athletic step, the perilous leap, the box on the ear, and the fisticuff.

4. We declare that the world’s wonder has been enriched by a fresh beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car with its trunk adorned by great exhaust pipes like snakes with an explosive breath … a roaring car that seems to be driving under shrapnel, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

5. We want to sing the man who holds the steering wheel, whose ideal stem pierces the Earth, itself launched on the circuit of its orbit.

6. The poet must expend himself with warmth, refulgence, and prodigality, to increase the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

7. There is no more beauty except in struggle. No masterpiece without an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent attack against the unknown forces, summoning them to lie down before man.

8. We stand on the far promontory of centuries!… What is the use of looking behind us, since our task is to smash the mysterious portals of the impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We live already in the absolute, since we have already created the eternal omnipresent speed.

9. We want to glorify war — the only hygiene of the world —

militarism, patriotism, the anarchist’s destructive gesture, the fine Ideas that kill, and the scorn of woman.

10. We want to demolish museums, libraries, fight against moralism, feminism, and all opportunistic and utilitarian cowardices.

11. We shall sing the great crowds tossed about by work, by pleasure, or revolt; the many-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals; the nocturnal vibration of the arsenals and the yards under their violent electrical moons; the gluttonous railway stations swallowing smoky serpents; the factories hung from the clouds by the ribbons of their smoke; the bridges leaping like athletes hurled over the diabolical cutlery of sunny rivers; the adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; the broad-chested locomotives, prancing on the rails like great steel horses curbed by long pipes, and the gliding flight of airplanes whose propellers snap like a flag in the wind, like the applause of an enthusiastic crowd.

Futurists had a disdain for inherited artistic traditions.

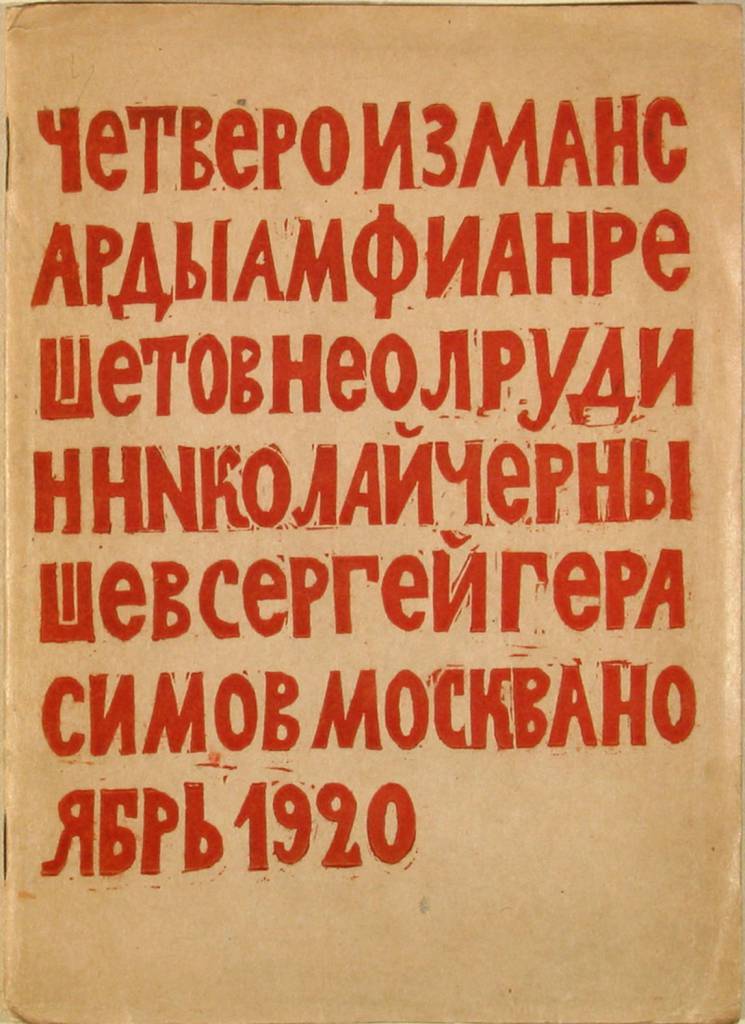

In 1917, Russian futurists David Burliuk, Alexander Kruchenykh, Vladmir Mayakovsky and Victor Khlebnikov produced their own manifesto: A Slap in the Face of Public Taste:

We alone was the face of our Time. Through us the horn of time blows in the art of the world.

The past is too tight. The Academy and Pushkin are less intelligible than hieroglyphics.

Throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the Ship of Modernity.

He who does not forget his first love will not recognize his last.

Who, trustingly, would turn his last love toward Balmont’s perfumed lechery? Is this the reflection of today’s virile soul?

Who, faint-heartedly, would fear tearing from warrior Bryusov’s black tuxedo the paper armor-plate? Or does the dawn of unknown beauties shine from it?

Wash your hands which have touched the filthy slime of the books written by the countless Leonid Andreyevs.

All those Maxim Gorkys, Krupins, Bloks, Sologubs, Remizovs, Averchenkos, Chornys, Kuzmins, Bunins, etc. need only a dacha on the river. Such is the reward fate gives tailors.

From the heights of skyscrapers we gaze at their insignificance!…

We order that the poets’ rights be revered:

To enlarge the scope of the poet’s vocabulary with arbitrary and derivative words (Word-novelty).

To feel an insurmountable hatred for the language existing before their time.

To push with horror off their proud brow the Wreath of cheap fame that You have made from bathhouse switches.

To stand on the rock of the word “we” amidst the sea of boos and outrage.

And if for the time being the filthy stigmas of your “common sense” and “good taste” are still present in our lines, these same lines for the first time already glimmer with the Summer Lightning of the New Coming Beauty of the Self-sufficient (self-centered) Word.

Josh Jones adds:

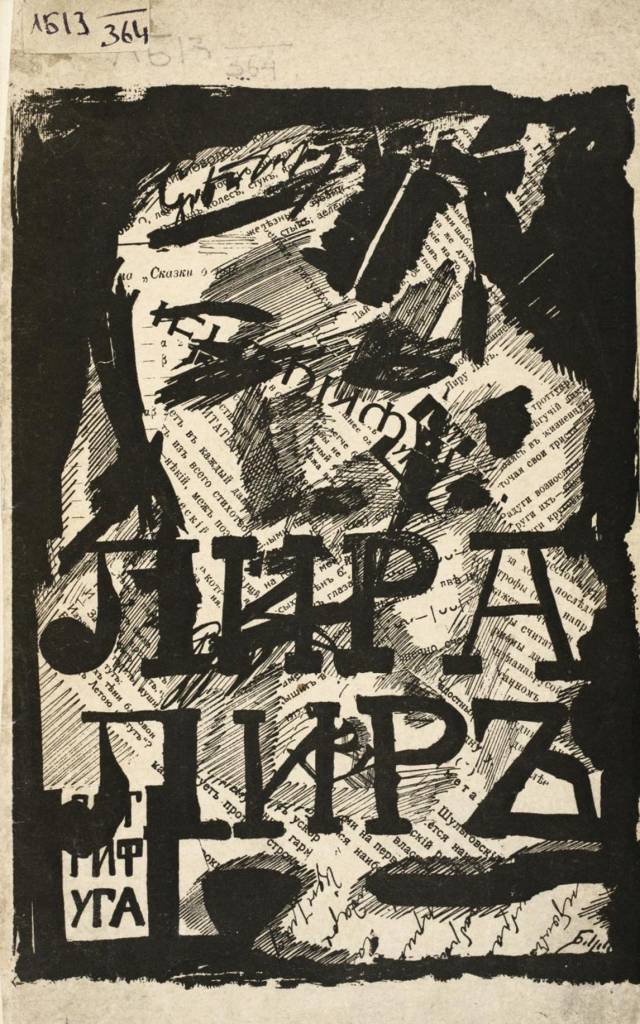

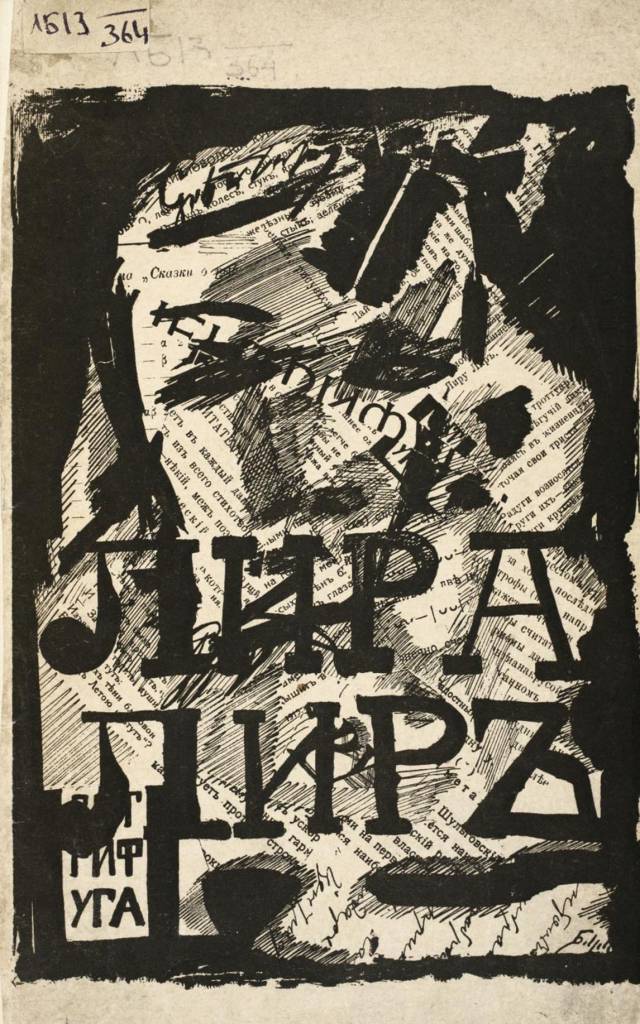

Like the Italian Futurists, these avant-garde Russian artists and poets were, writes Poets.org, “preoccupied with urban imagery, eccentric words, neologisms, and experimental rhymes.” One of the movement’s most inventive members, Velimir Khlebnikov, wrote poetry that ranged from “dense and private neologisms to exotic verse forms written in palindromes.” Most of his poetry “was too impenetrable to reach a popular audience,” and his work included not only experiments with language on the page, but also avant-garde industrial sound recording.

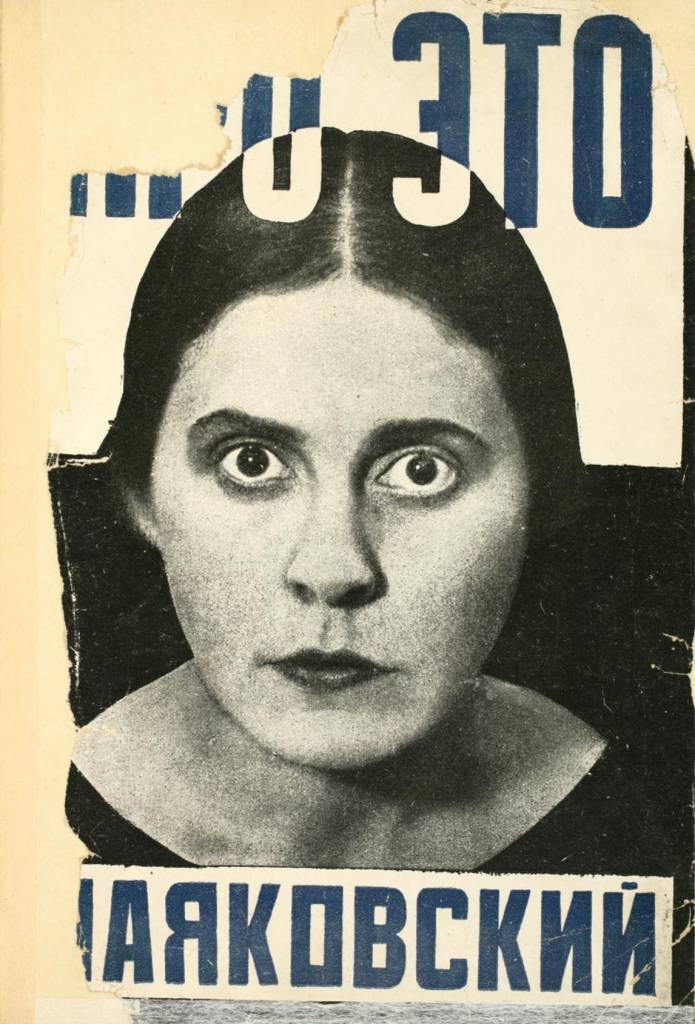

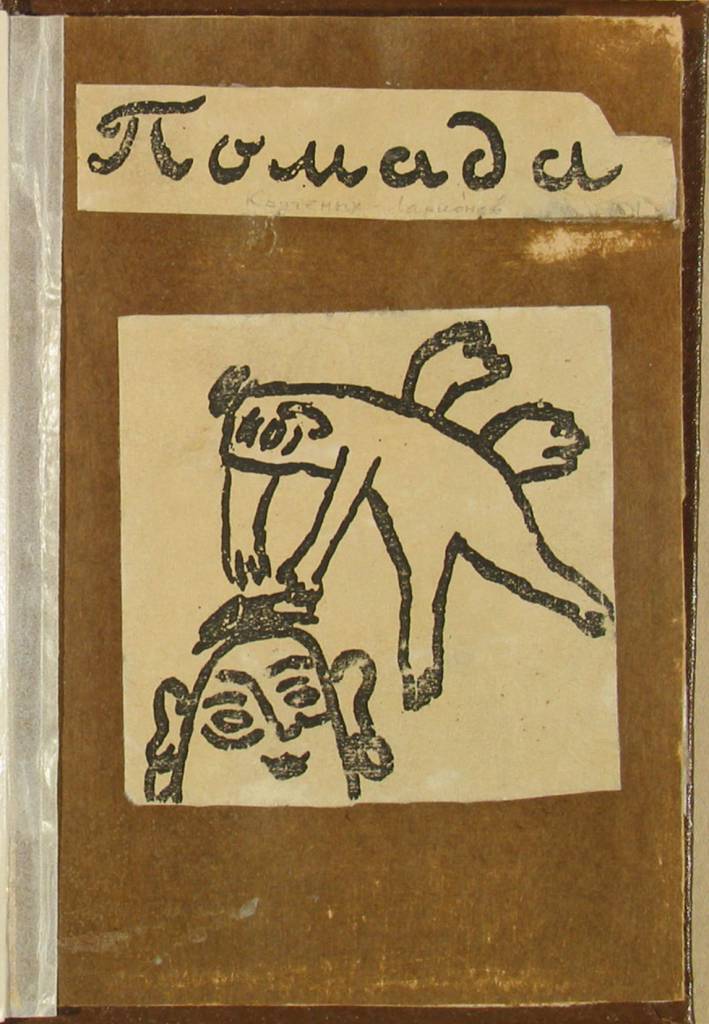

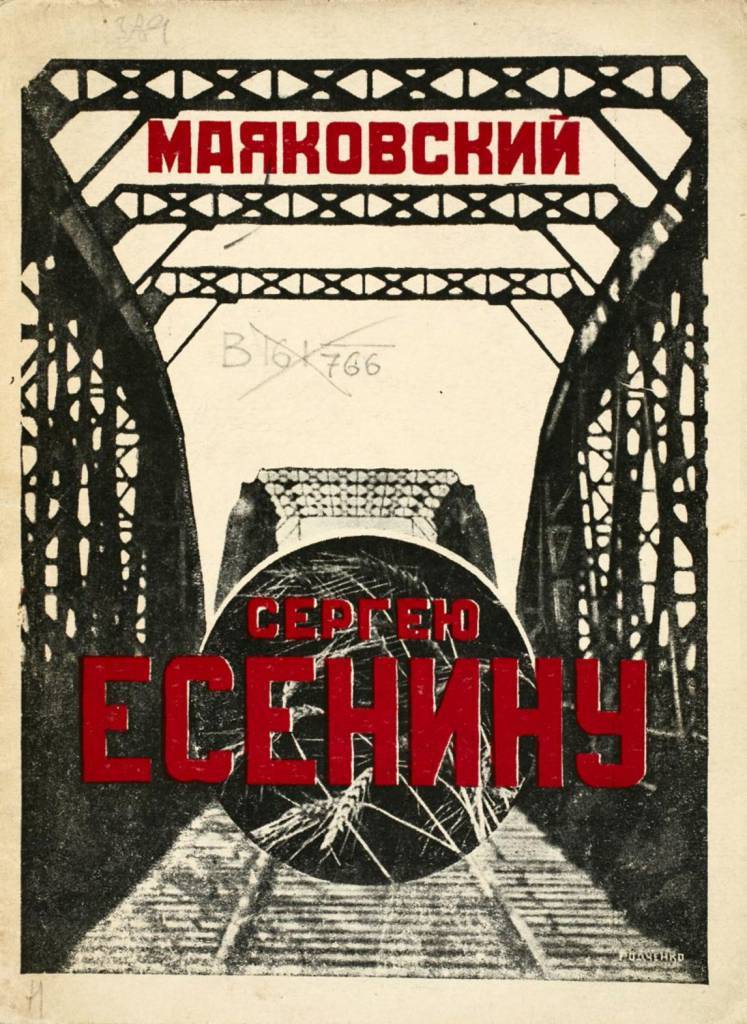

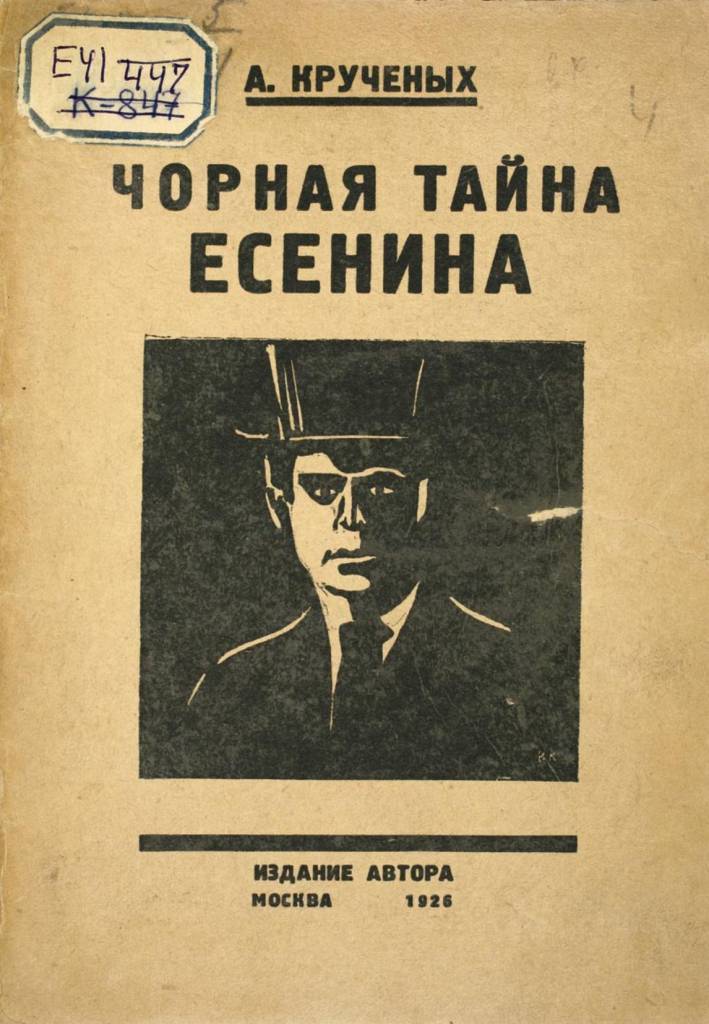

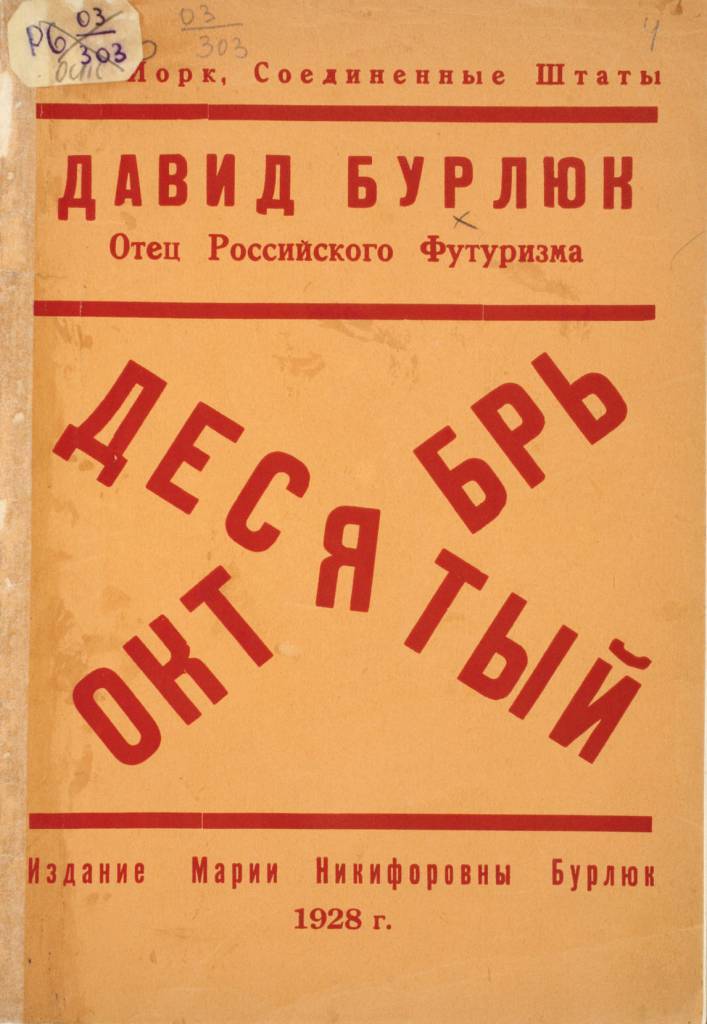

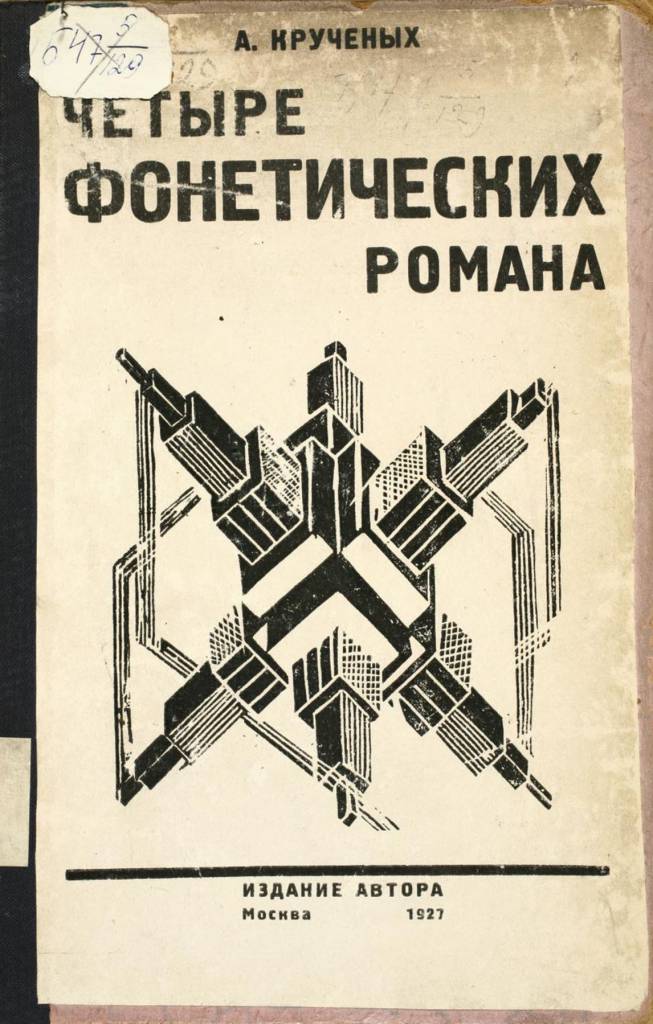

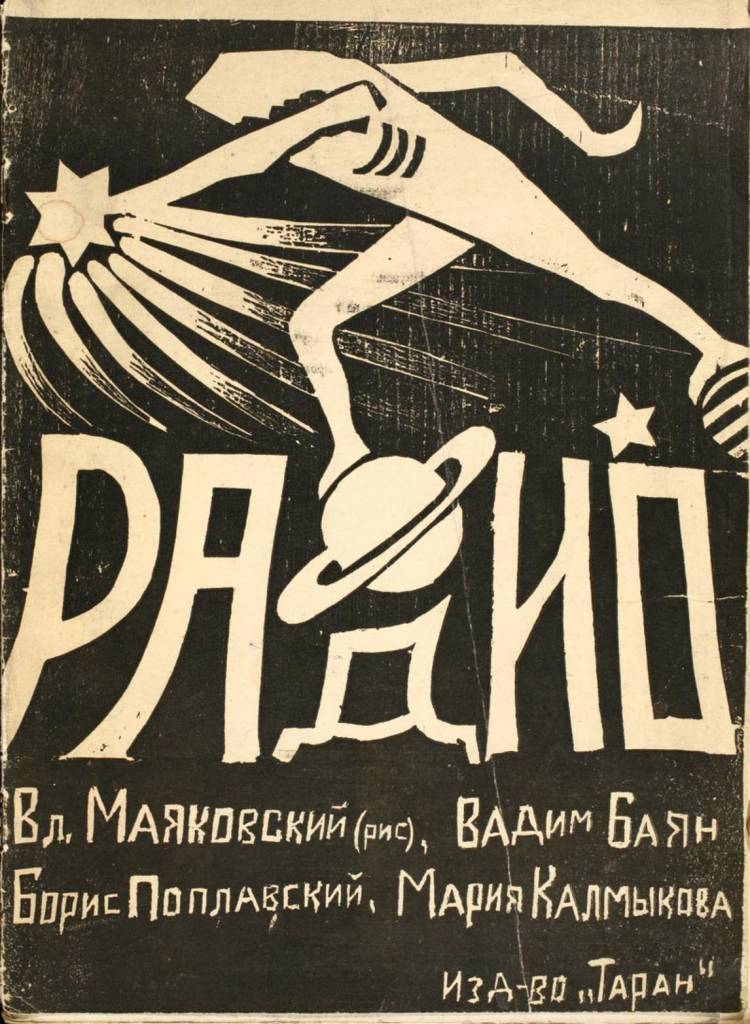

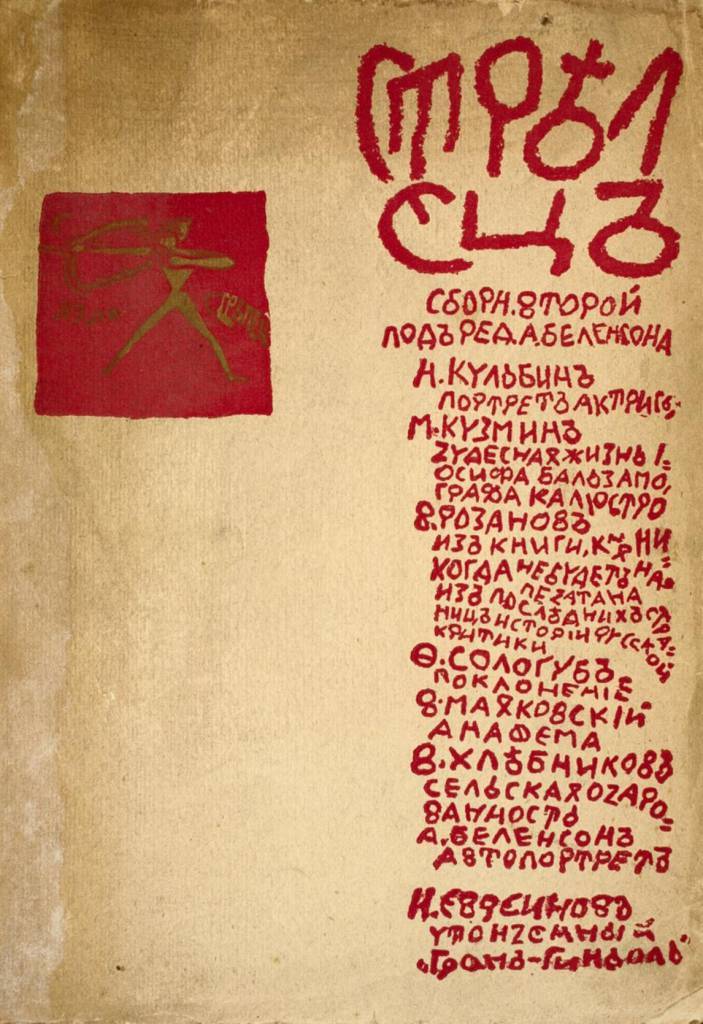

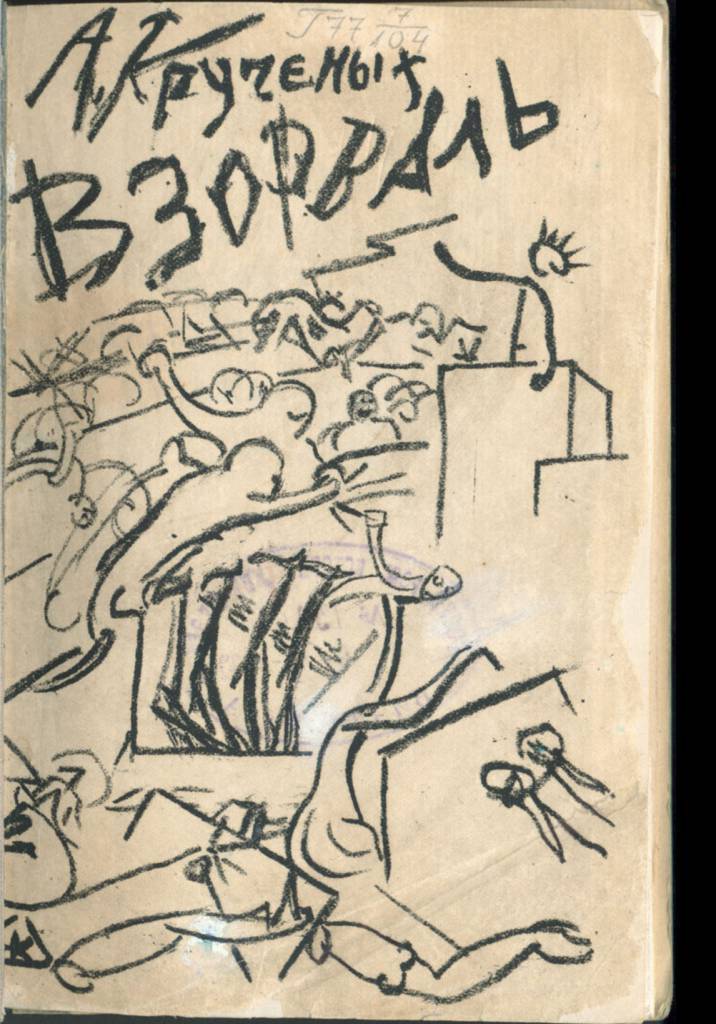

Khlebnikov’s experiments in linguistic sound and form became known as “Zaum,” a word that can be translated as “transreason,” or “beyond sense.” He pioneered his techniques with another major Futurist poet, Aleksei Kruchenykh, who may have been, writes Monoskop, “the most radical poet of Russian Futurism.” The most famous name to emerge from the movement, Vladimir Mayakovsky, embodied Futurism’s confident individualism, his poetics “a mixture of extravagant exaggerations and self-centered and arduous imagery.” Mayakovsky made a name for himself as an actor, painter, poet, filmmaker, and playwright. Even Stalin, who would soon preside over the suppression of the Russian avant-garde, called Mayakovsky after his death in 1930 “the best and most talented poet of the Soviet epoch.”

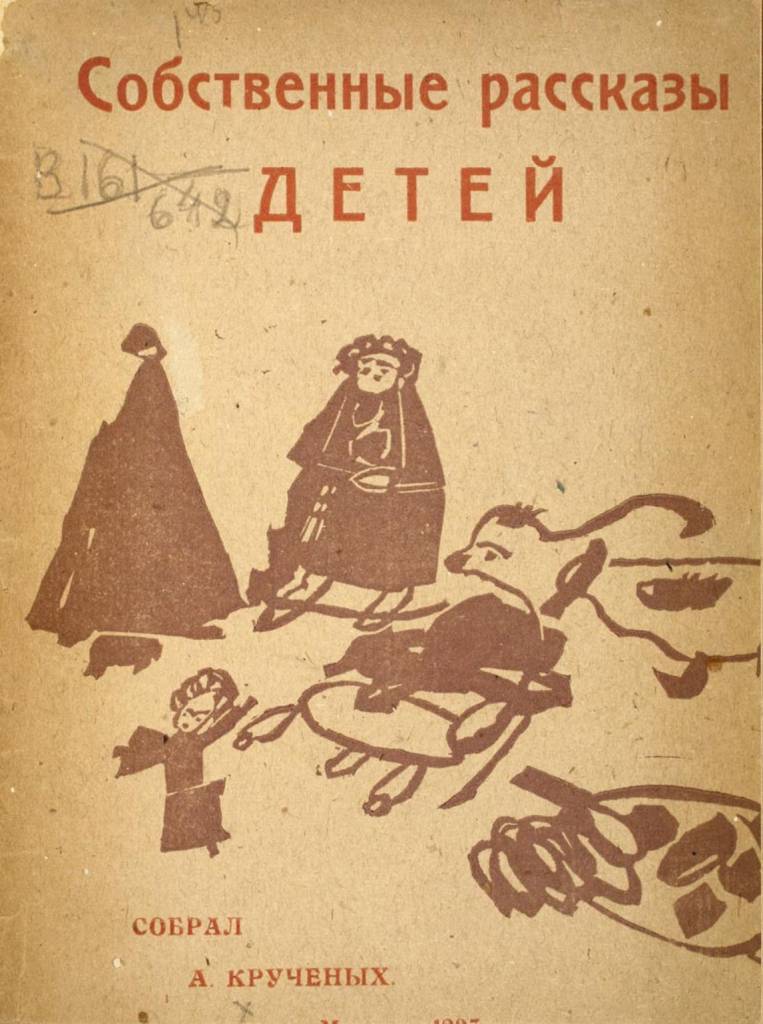

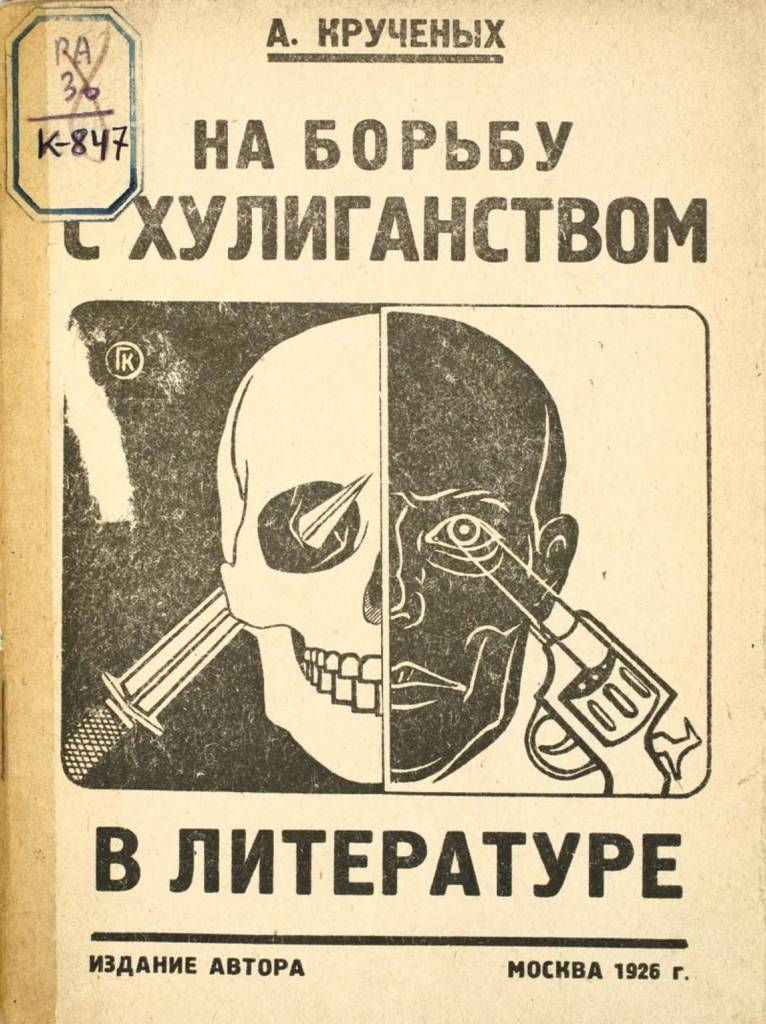

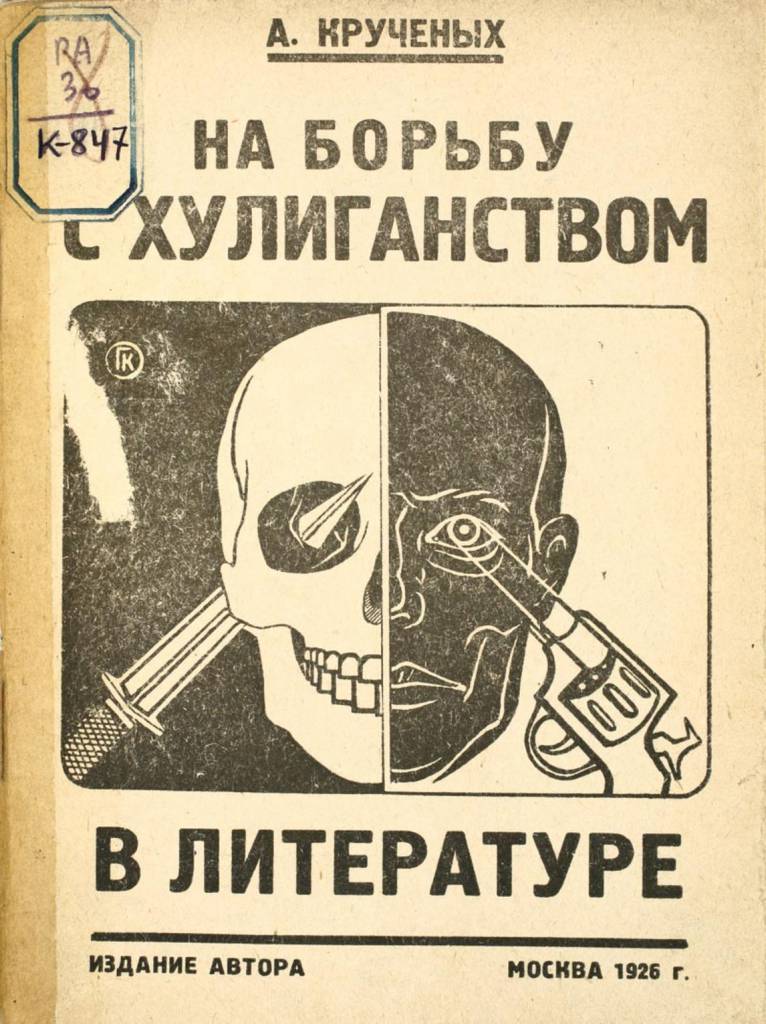

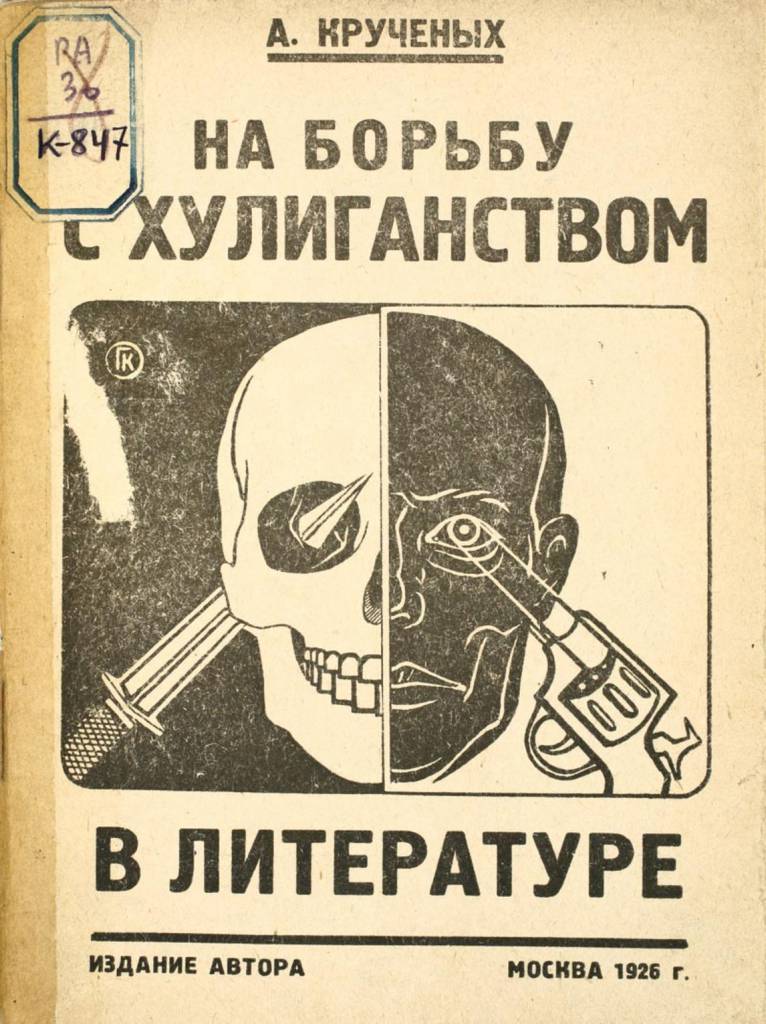

Kruchenykh AE on the fight against hooliganism in the literature: Production number 140. – M.: Publishing house. Aut. 1926

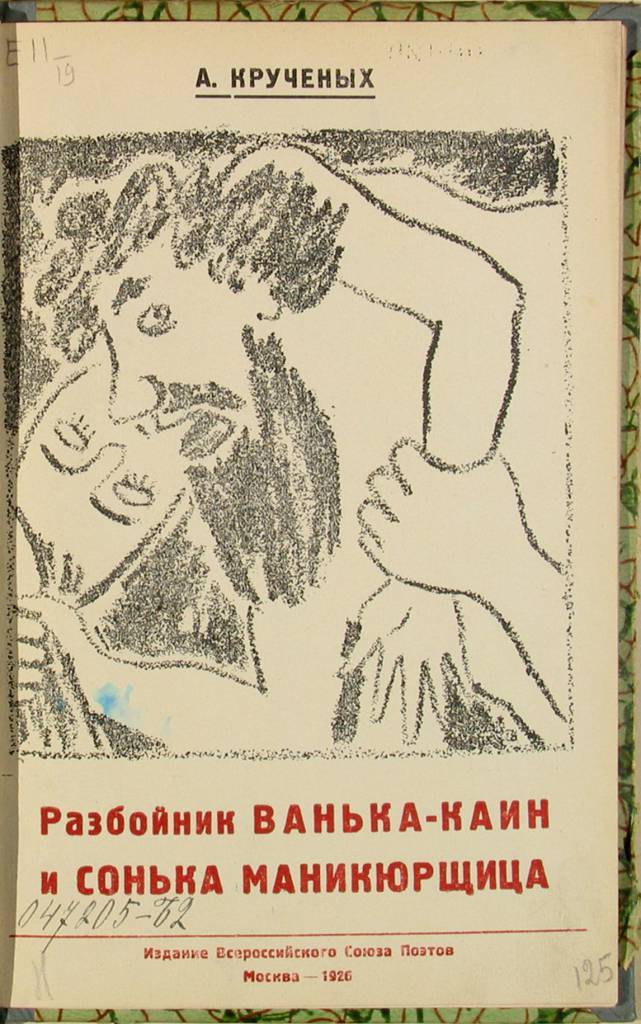

Kruchenykh AE Rogue Vaska-Cain and Sonya Manicurist: Criminal Novel: Book I-132. – M.: Publishing house. Proc. Poets Union 1925.

In A Poet’s Glossary

by Edward Hirsch, we learn:

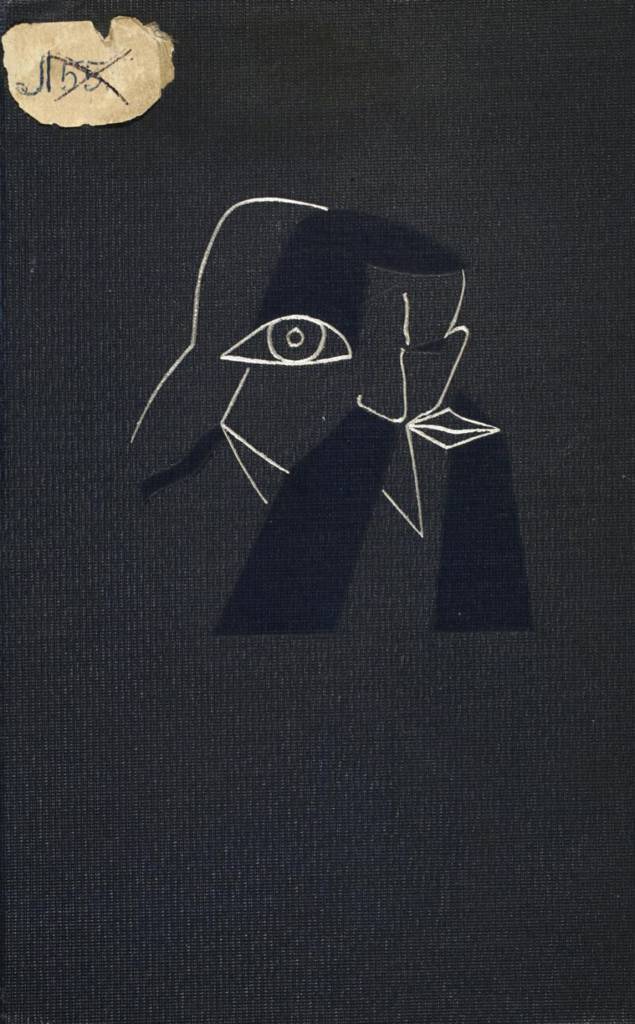

There were four distinct Russian futurist groups: Cubo-futurism, ego- futurism, the Mezzanine of Poetry, and Centrifuge. What these groups shared was a dedication to modernism and a determination to denounce each other.

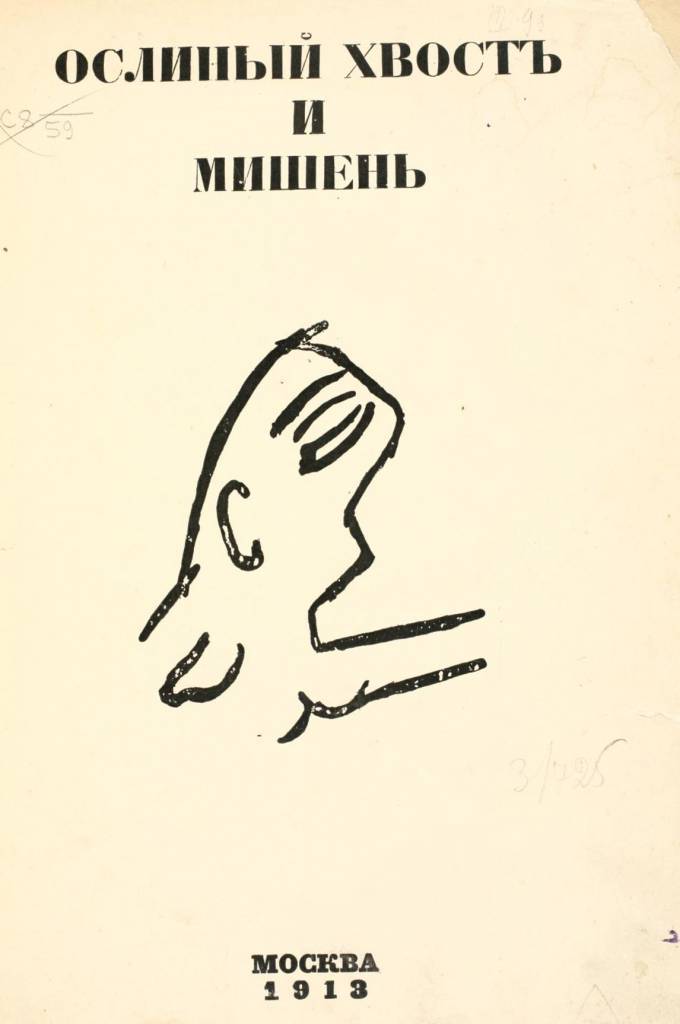

The Hylean Group developed into the Cubo-futurists, a group of painters who combined the Cubist techniques of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braques, and Juan Gris with the dynamism of the Italian futurists. Painters such as Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, and Kazimir Malevich were inspired by futurist poems, and they included various letters, at times even whole words, in their compositions. They treated words as material things.

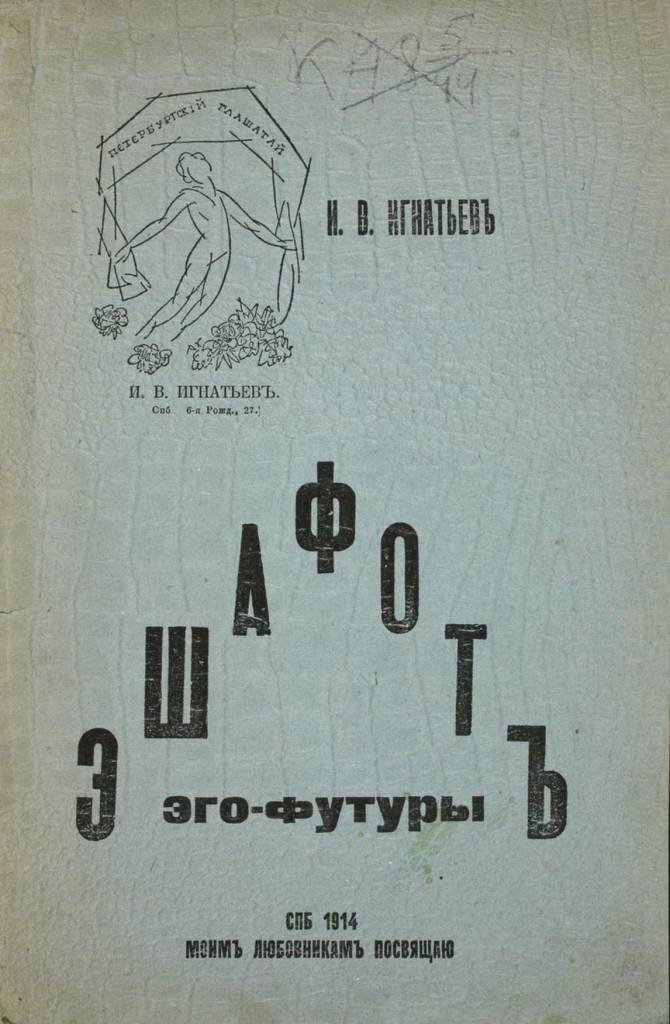

The ego-futurist collective paid direct homage to Marinetti and introduced the word futurism to the Russian literary scene. The aristocratic poet Igor Severyanin tried to create a new trend within futurism in 1911 with his small brochure Prolog (Ego-Futurism) that attacked the extreme objectivity of the Cubo-futurists and proposed an alternative subjectivity, which included a more ostentatious egoism and sensuality. “All of history lies before us,” Graal-Arelsky (the pseudonym of Stepan Stepanovich Petrov) argued in “Egopoetry in Poetry” (1912): “Nature created us. Only She should rule us in our actions and efforts. She placed egoism inside of us; we should develop it. Egoism unites us all, because we are all egoists.”

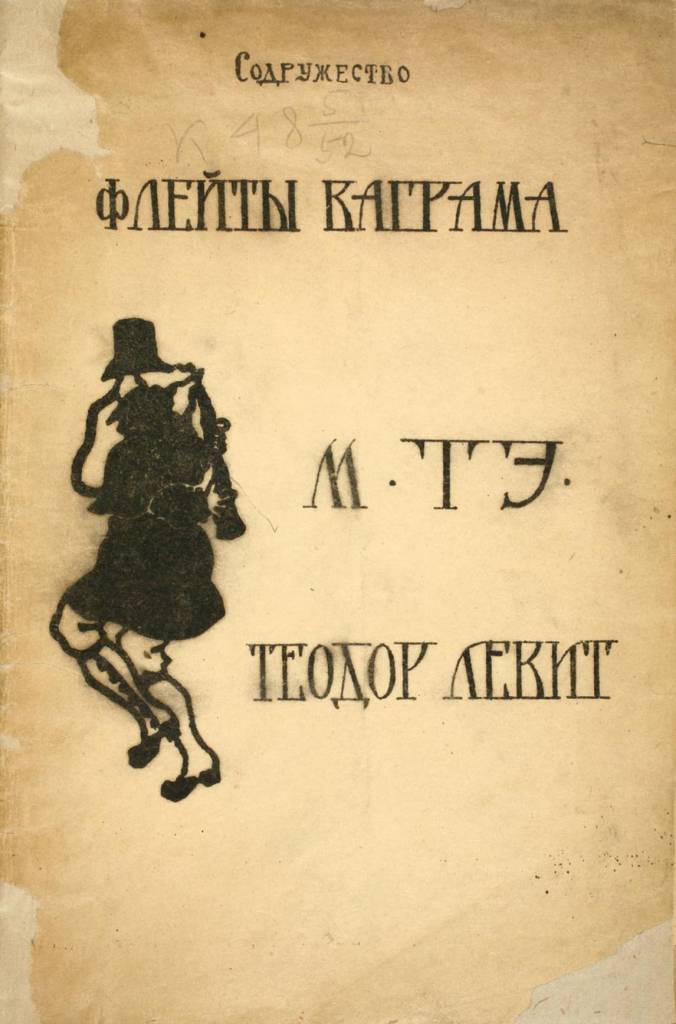

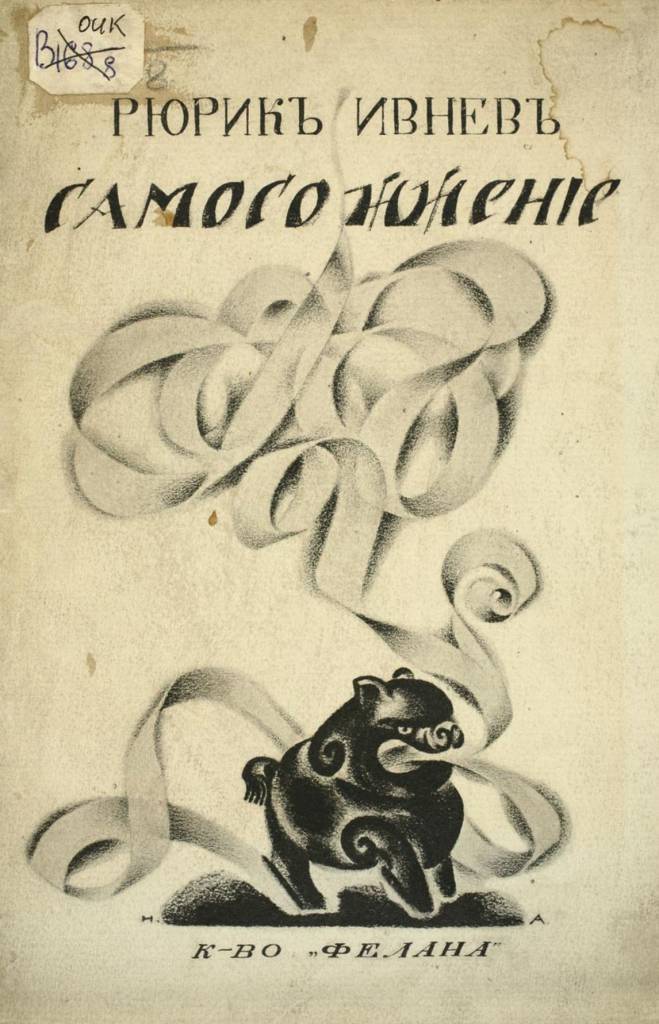

Lev Zak introduced the short-lived movement the Mezzanine of Poetry, which consisted of Konstantin Bolshakov, Riuruk Ivnev, Vadim Shershenevich, Marinetti’s eager translator, and Zak himself. “Darling! Please come to the opening of our Mezzanine!” Zak wrote in his invitation to the movement: “The image of the Most Charming One, which each of us has locked in his soul, makes all things, all thoughts, and all passions equally poetic.”

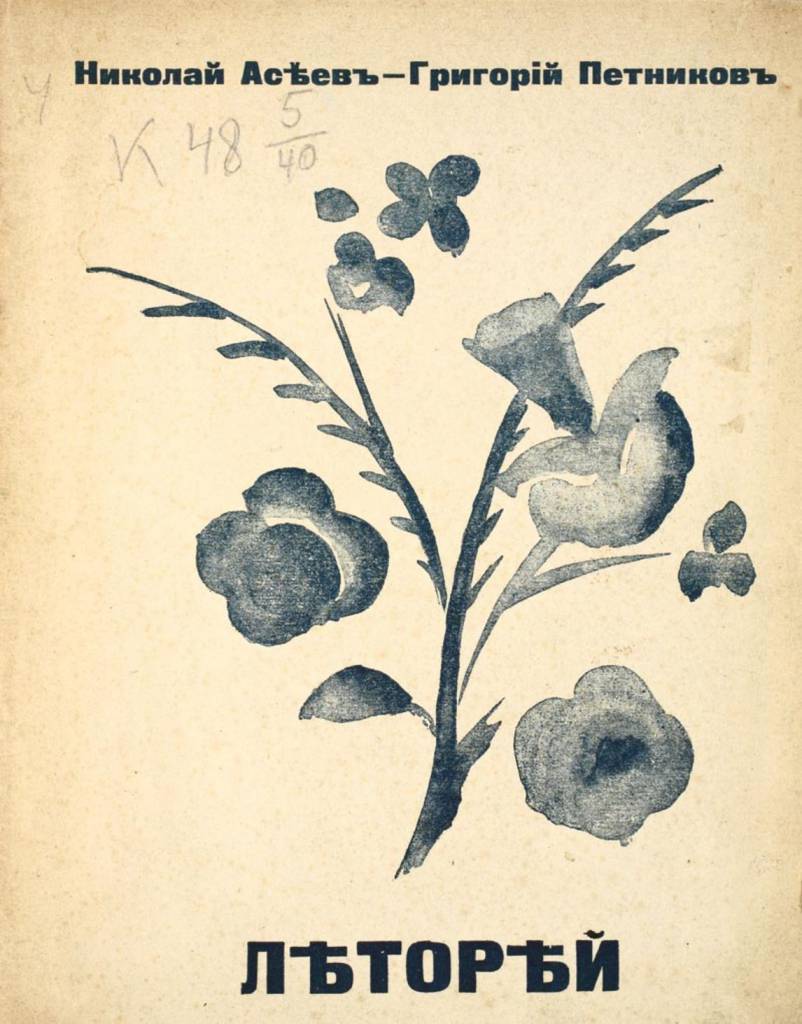

Centrifuge was the last offshoot of futurism before the Russian Revolution. It was launched in 1914 by Sergei Bobrov, Nikolay Aseyev, and Boris Pasternak with the almanac Rukonog (a trans-rational coinage that meant Handfoot). Pasternak cosigned a scurrilous charter denouncing rival futurists. This led to a settling of accounts between the anti-Centrifuge futurists and the Centrifuge futurists at a Moscow café on a hot day in May 1914. But at the meeting, Pasternak was infatuated with Mayakovsky, his supposed enemy, and immediately opted out of the proposed feud. “I carried the whole of him with me that day from the boulevard into my life,” he said later. “But he was enormous; there was no holding on to him when apart from him. And I kept losing him.”

Kruchenykh AE on the fight against hooliganism in the literature: Production number 140. – M.: Publishing house. Aut. 1926

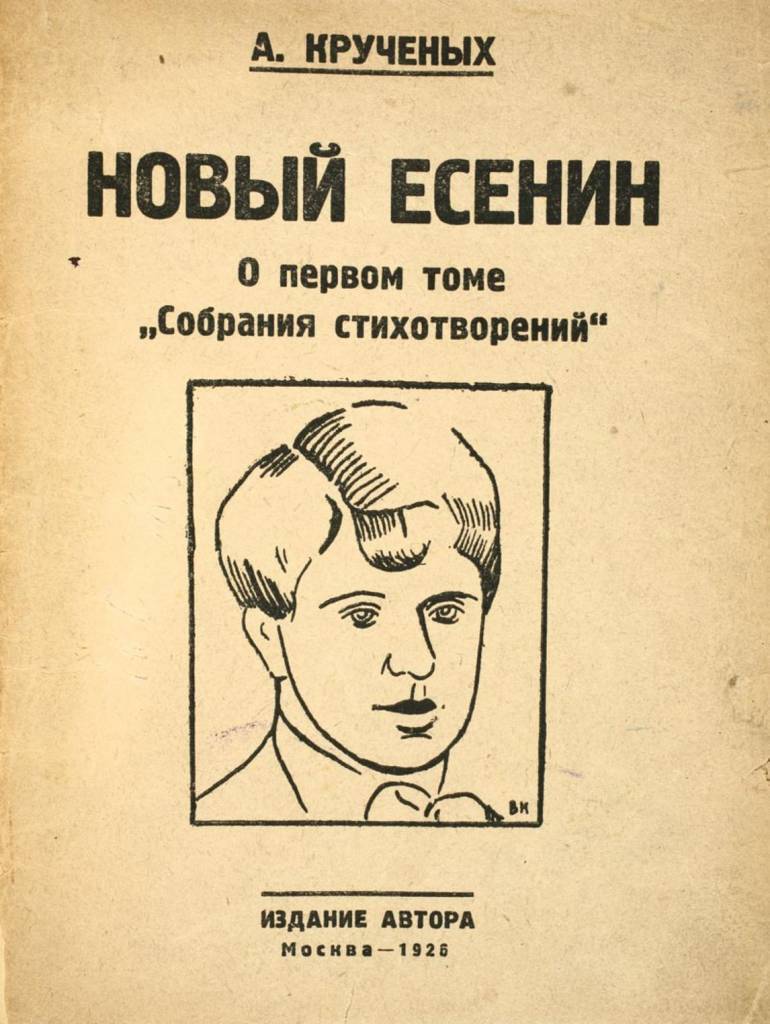

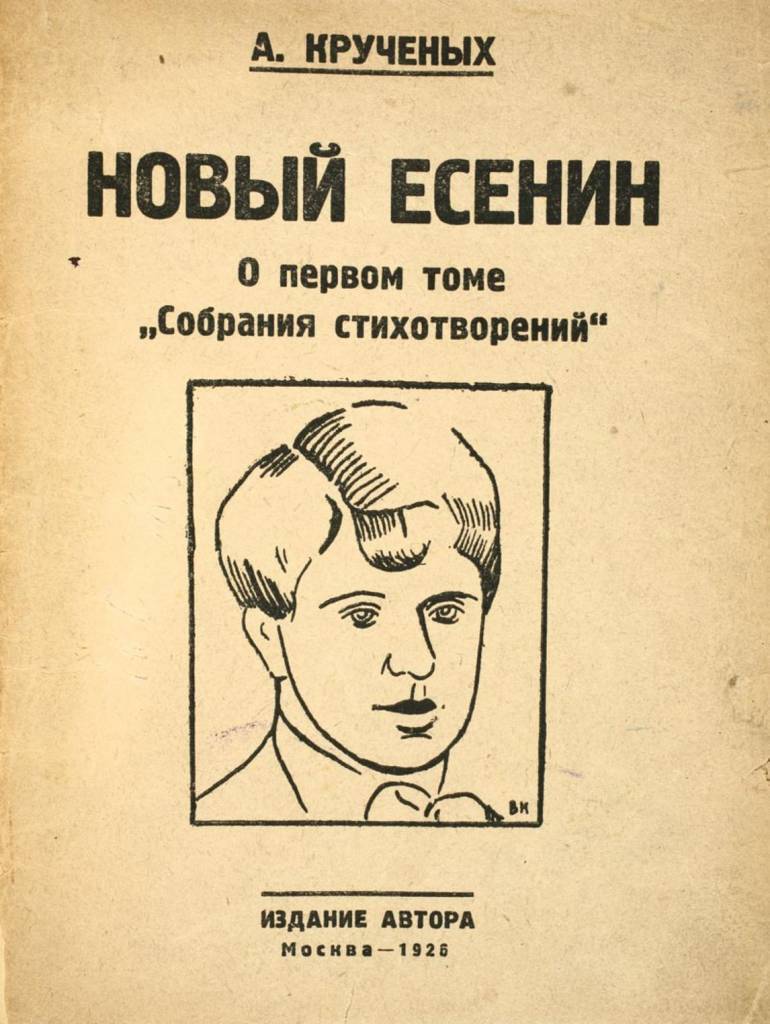

Kruchenykh AE New Yesenin. On the first volume of the Collected Poems: Production number 138. – M.: Publishing house. Aut. 1926

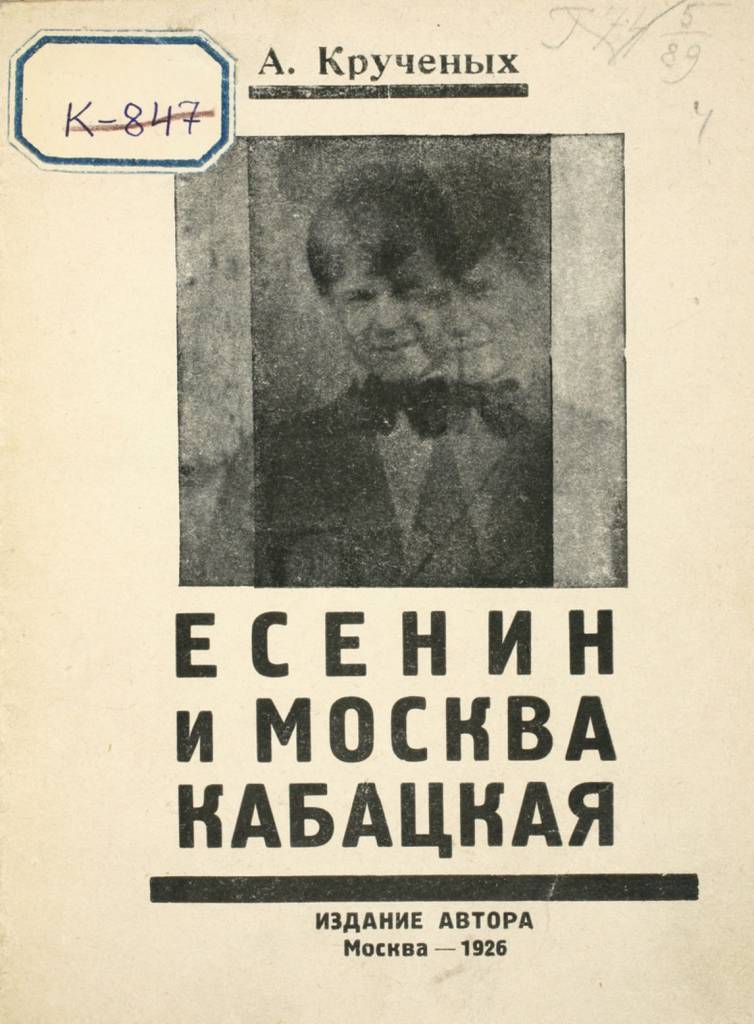

Yesenin and Moscow tavern. Love bully. Two autobiography Esenina: Product number 135a. – M.: Publishing house. author, 1926

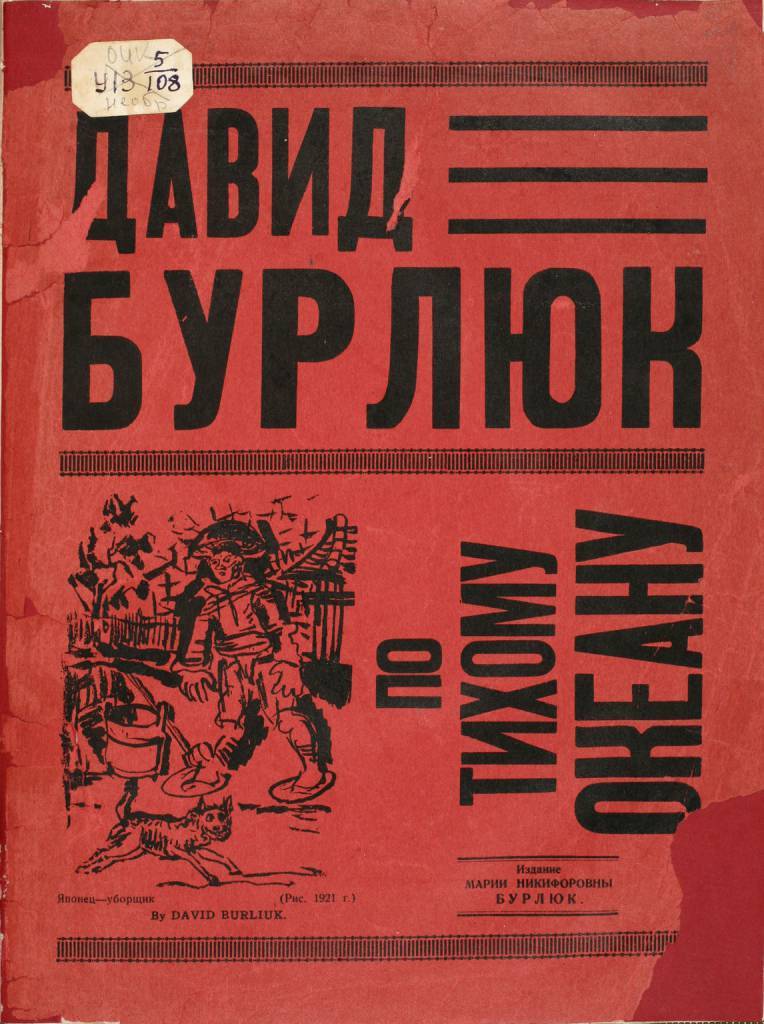

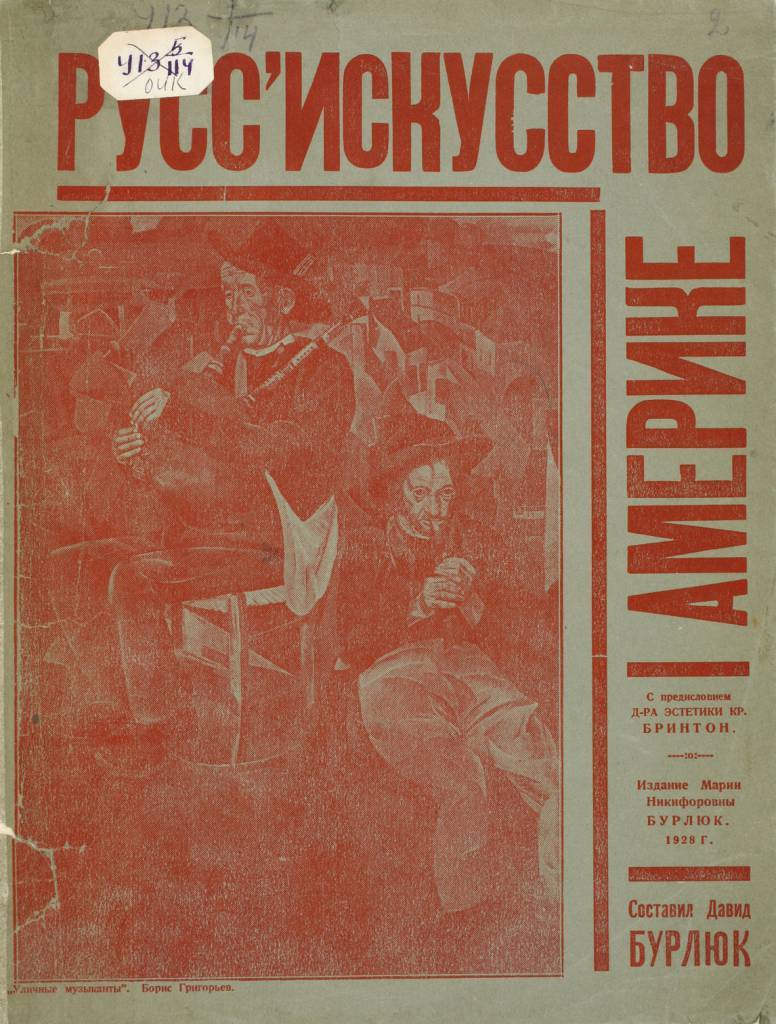

Burliuk DD Russian artists in America: Information on the history of Russian art in 1917 – 1928. – New-York: Acad. Mary Nikiforovna Burliuk 1928

Kruchenykh AE Ironiada: Lyrics. May-June 1930. – M.: Steklopechat Chef Common. People’s Commissariat of 1930.

Kruchenykh AE on the fight against hooliganism in the literature: Production number 140. – M.: Publishing house. Aut. 1926

Kruchenykh AE New Yesenin. On the first volume of the Collected Poems: Production number 138. – M.: Publishing house. Aut. 1926

via Monoskop

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.