In the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s marijuana was The Devil’s Harvest, an Assassin of Youth that would inflict tokers with a new medical condition called Refer Madness, curable only by severe sobriety.

Marijuana destroyed the human spirit. It made fools and whores of young women. The evil weed turned men into monsters of the occult. Teens and their parents should be in doubt: cannabis was a moral choice. Smoke it and be bad to the core in his life and the ever after.

Using dope turned juveniles into “fiends”. Sure the weed makes the chow mein taste delicious and the syncopated sounds groovy and magical, but very soon you are raiding a bank to raise money for your next fix, and plotting to hollow out a ravished vigin and use her for a novelty bong.

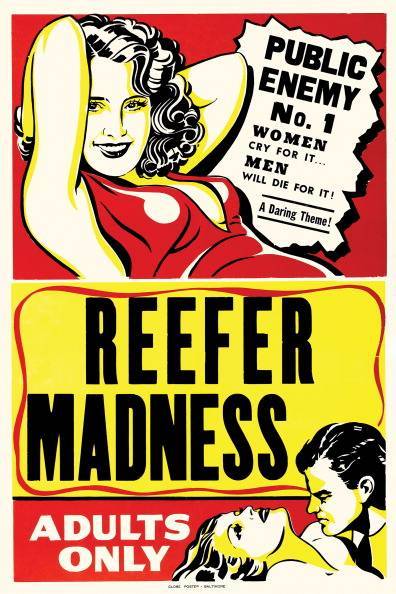

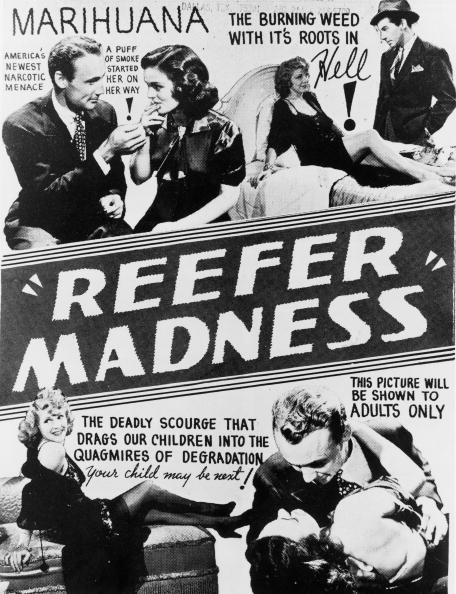

A still from ‘Reefer Madness’, an anti-drugs exploitation film, dealing with the pitfalls of marijuana smoking, directed by Louis J. Gasnier, 1936. Among the cast are: Standing, left to right: Carleton Young (1905 – 1994), Dave O’Brien (1912 – 1969), and Thelma White (1910 – 2005). Seated on the left is Lillian Miles (1907 – 1972). (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The trailer for the movie Reefer Madness (1936) looks a lot like an overblown try-too-hard parody. It wasn’t. It was being played straight:

Reefer Madness is the most enduring title of the moral marijuana movie craze.

The Reefer Madness Teaching Museum reviews that film’s forerunners:

NOTCH NUMBER ONE: (1924)

AKA: The First Notch

Ben Wilson Productions. Dist Arrow Film Corp. 13 Sep 1924 [cl4 Apr 1924; LP200761. Si; b&w. 35mm. 5 reels, 4,746 ft.

Story Daniel F. Whitcomb.

Cast: Ben Wilson, Marjorie Daw.

Western melodrama. Tom Watson, foreman of the Moore Ranch, is silently in love with Dorothy, the owner’s daughter, who is engaged to Dave Leonard. One night Dave becomes violent after smoking some marihuana (loco weed) given him by Pete, a ranch hand recently fired by Tom. Moore tries to restrain Dave. Pete, seeking revenge, shoots Moore . Tom, believing Dave guilty, takes the blame and becomes a fugitive. He is captured after rescuing 6-year-old Dickie Moore, who had become lost on the desert. Pete is found dead, but with a confession that frees Tom.

Jewel Robbery (1932)

As the dapper criminal known simply as “The Robber,” William Powell requires no machine guns to hold up a plush Vienna jewelry shop. Plying his victims with marijuana cigarettes and the police with blonde female witnesses, he gingerly relieves the shop of its diamonds; it’s as easy as slipping a bracelet off a woman’s wrist while kissing her hand. Kay Francis stars with Powell as Baroness Teri, who comes to realize that the love of a jewel thief is even more exciting than the jewels themselves. A sophisticated, Lubitsch-like caper, Jewel Robbery was called in the original New York Times review, “nervous, brittle comedy…. The situation is as capricious, the dialogue as sprightly and the settings as sinfully luxurious as they ought to be.”

Directed by William Dieterle. Written by Erwin Gelsey from the play by Laszlo Fodor. With William Powell, Kay Francis, Hardie Albright. (1932, 68 mins, Print from MGM/United Artists)

The Atlantic provides historical context:

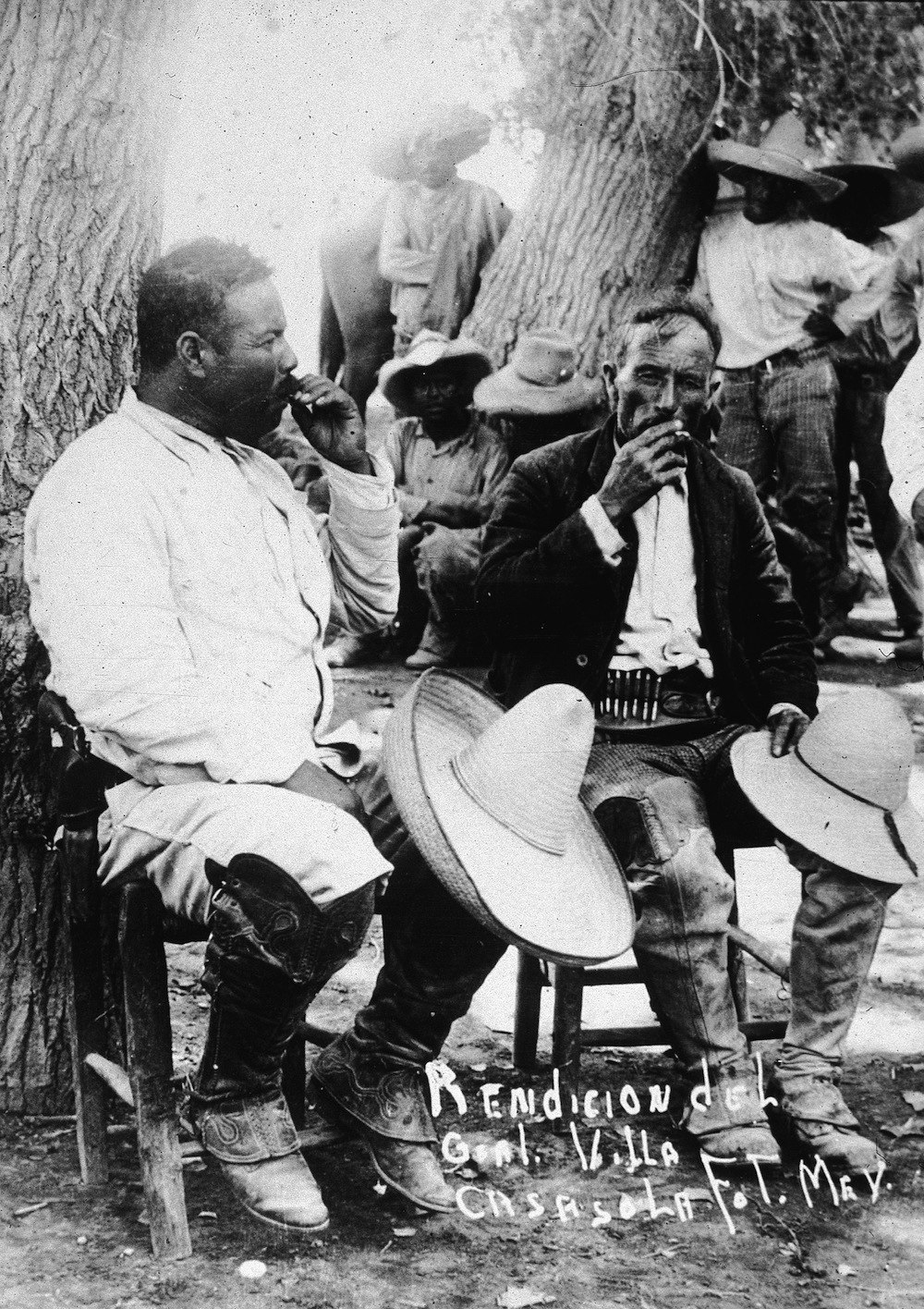

The political upheaval in Mexico that culminated in the Revolution of 1910 led to a wave of Mexican immigration to states throughout the American Southwest. The prejudices and fears that greeted these peasant immigrants also extended to their traditional means of intoxication: smoking marijuana. Police officers in Texas claimed that marijuana incited violent crimes, aroused a “lust for blood,” and gave its users “superhuman strength.”

Mexican revolutionary leader Pancho Villa (1878 – 1923) (L) sits against a tree with a fellow soldier, their straw hats over their knees, following the Mexican Revolution of 1911. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Rumors spread that Mexicans were distributing this “killer weed” to unsuspecting American schoolchildren. Sailors and West Indian immigrants brought the practice of smoking marijuana to port cities along the Gulf of Mexico. In New Orleans newspaper articles associated the drug with African-Americans, jazz musicians, prostitutes, and underworld whites. “The Marijuana Menace,” as sketched by anti-drug campaigners, was personified by inferior races and social deviants.

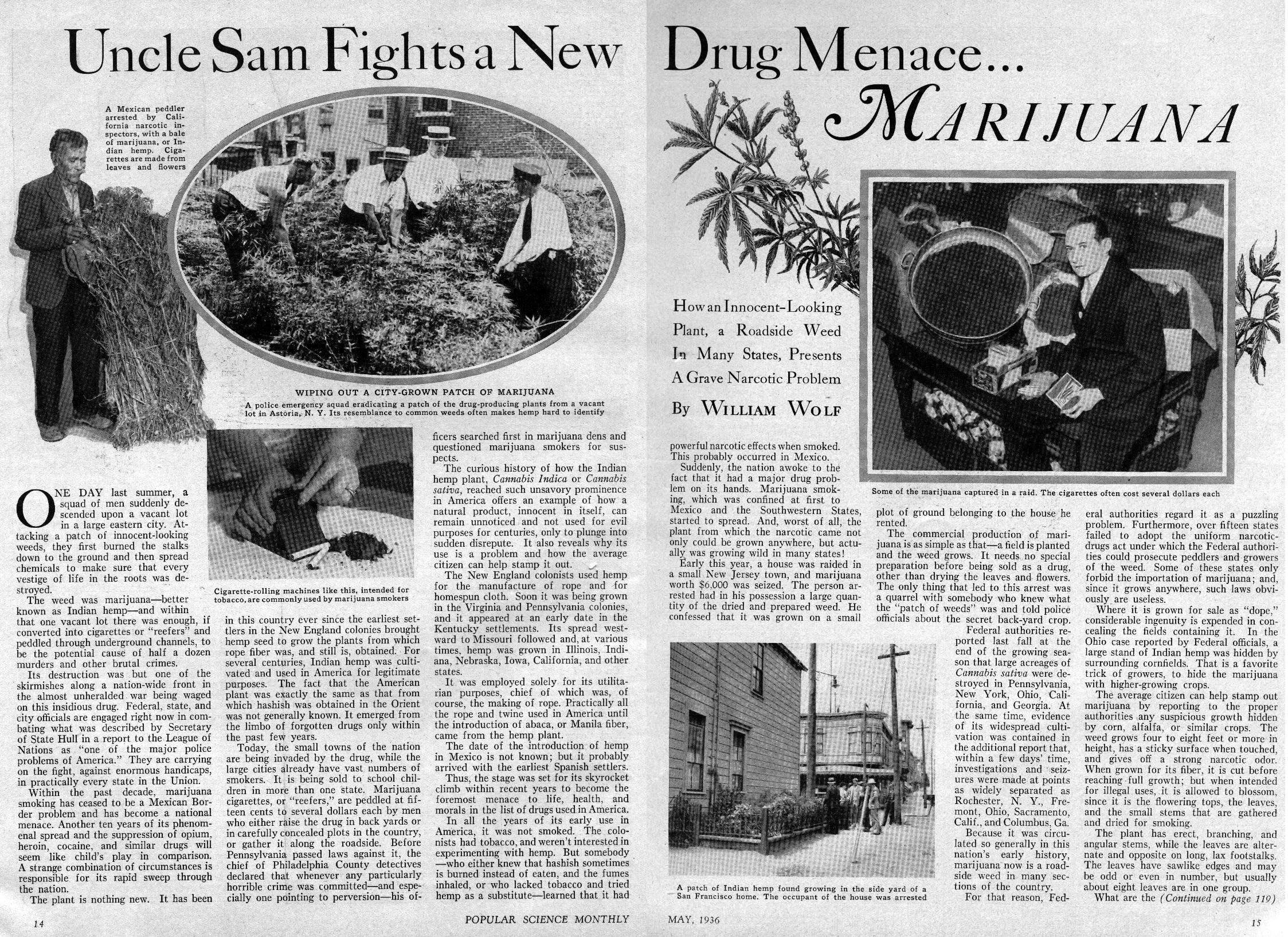

Popular Mechanix magazine 1937: “The date of the introduction of hemp in Mexico is not known; but it probably arrived with the earliest Spanish settlers.

Thus, the stage was set for its skyrocket climb within recent years to become the foremost menace to life, health, and morals in the list of drugs used in America.”

In 1914 El Paso, Texas, enacted perhaps the first U.S. ordinance banning the sale or possession of marijuana; by 1931 twenty-nine states had outlawed marijuana, usually with little fanfare or debate. Amid the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment fueled by the Great Depression, public officials from the Southwest and from Louisiana petitioned the Treasury Department to outlaw marijuana. Their efforts were aided by a lurid propaganda campaign. “Murder Weed Found Up and Down Coast,” one headline warned; “Deadly Marijuana Dope Plant Ready For Harvest That Means Enslavement of California Children.”

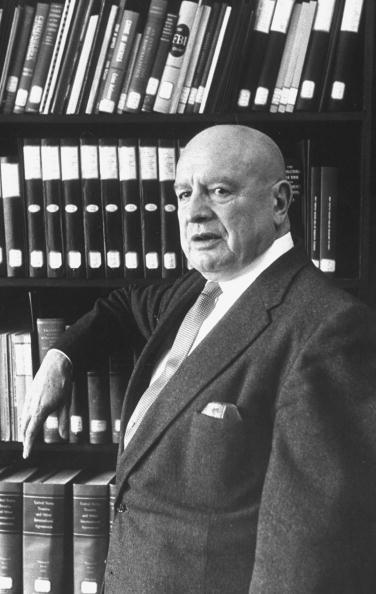

Henry J. Anslinger, the commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, at first doubted the seriousness of the problem and the need for federal legislation, but soon he pursued the goal of a nationwide marijuana prohibition with enormous gusto. In public appearances and radio broadcasts Anslinger asserted that the use of this “evil weed” led to killings, sex crimes, and insanity. He wrote sensational magazine articles with titles like “Marijuana: Assassin of Youth.”

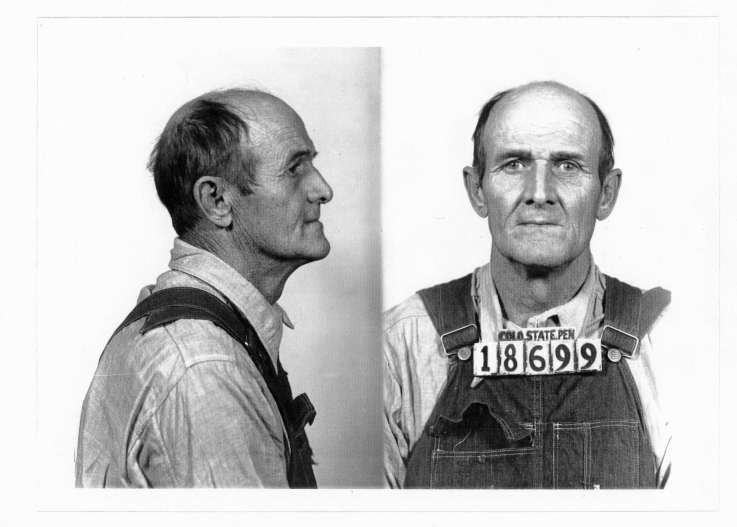

Samuel R. Caldwell (via)

In 1937 Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act, effectively criminalizing the possession of marijuana throughout the United States. A week after it went into effect, a fifty-eight-year-old marijuana dealer named Samuel R. Caldwell became the first person convicted under the new statute. Although marijuana offenders had been treated leniently under state and local laws, Judge J. Foster Symes, of Denver, lectured Caldwell on the viciousness of marijuana and sentenced him to four hard years at Leavenworth Penitentiary.

A poster advertising ‘Reefer Madness’, an anti-drugs exploitation film, dealing with the pitfalls of marijuana smoking, directed by Louis J. Gasnier, 1936. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, PhD “State Medical Marijuana Laws: Understanding the Laws and Their Limitations”, Journal of Public Health Policy, 2002:

“By the time the federal government passed the Marihuana Tax Act in [Oct.] 1937, every state had already enacted laws criminalizing the possession and sale of marijuana. The federal law, which was structured in a fashion similar to the 1914 Harrison Act, maintained the right to use marijuana for medicinal purposes but required physicians and pharmacists who prescribed or dispensed marijuana to register with federal authorities and pay an annual tax or license fee…

After the passage of the Act, prescriptions of marijuana declined because doctors generally decided it was easier not to prescribe marijuana than to deal with the extra work imposed by the new law.”

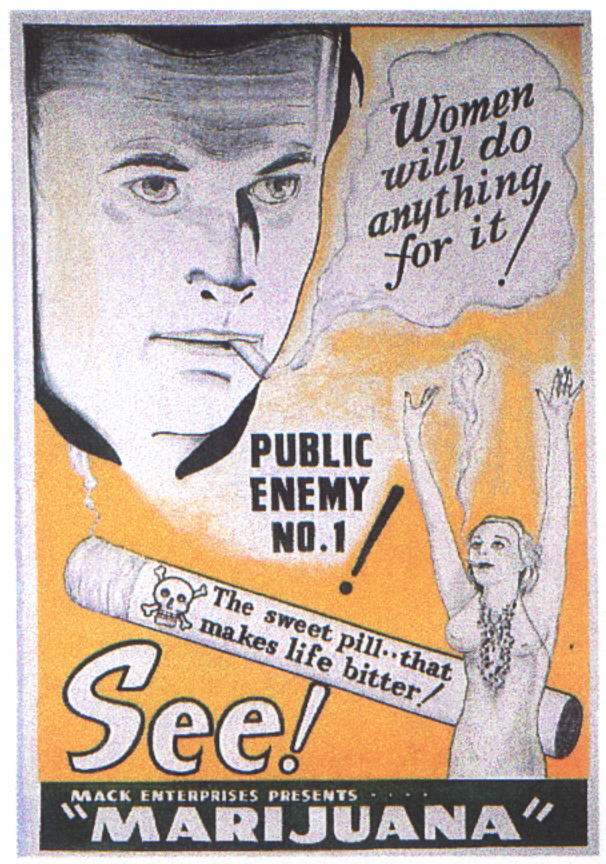

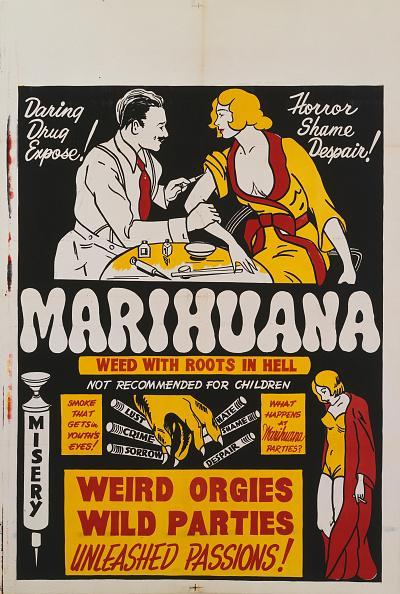

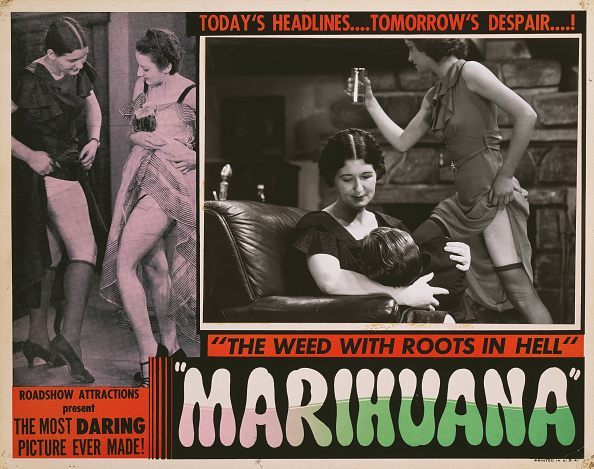

A poster for Dwain Esper’s 1936 crime film ‘Marihuana’. (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

“Marijuana was removed from the US Pharmacopeia in 1942, thus losing its remaining mantle of therapeutic legitimacy.” – American Medical Association (AMA)

A poster for Dwain Esper’s 1936 crime film ‘Marihuana’. (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

Congress includes marijuana in the Narcotics Control Act of 1956, which results in stricter mandatory sentences for marijuana-related offenses. A first-offense marijuana possession carries a minimum sentence of 2-10 years with a fine of up to $20,000. – “Busted: America’s War on Marijuana,” www.pbs.org (accessed July 21, 2010)

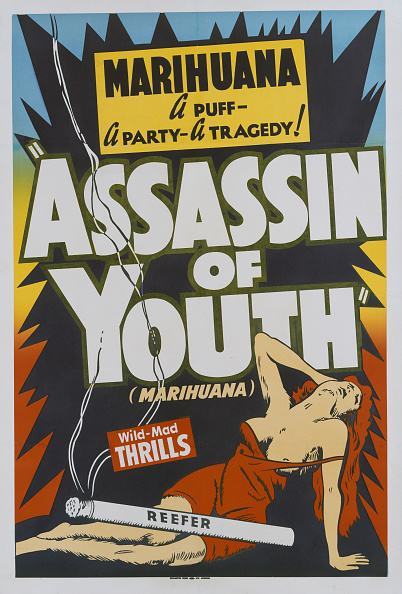

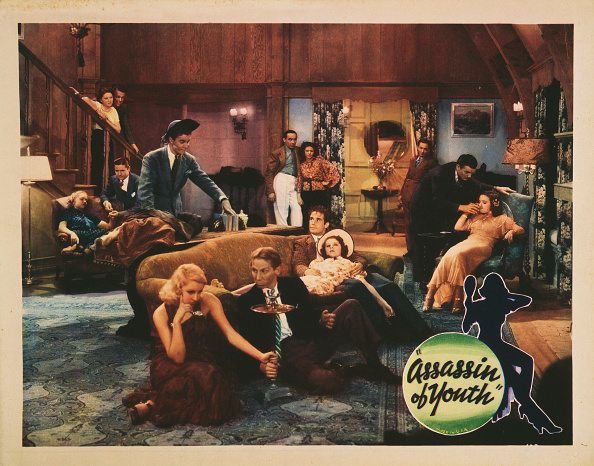

A poster for Elmer Clifton’s 1937 drama ‘Assassin of Youth’ . (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

A poster for Elmer Clifton’s 1937 drama ‘Assassin of Youth’. (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

In 1961, Harry J. Anslinger, U. S. Commissioner of Narcotics and Will Oursler shared his views on marijuana:

In 1930 there was no federal law against smoking marijuana, and the average American citizen in an average community had probably never heard of “reefers” or “tea” or other words in the argot of marijuana users. But by the middle thirties we began to see the serious effects of marijuana on our youth. An alarming increase in the smoking of marijuana reefers in 1936 continued to spread at an accelerated pace in 1937. Before this, use of reefers had been relatively slight and confined to the the Southwest, particularly along the Mexican border.

Seizures by state officers in these two years, however, had increased a hundred percent and by hundreds of pounds. Reports I received from thirty states showed an “invasion” by this drug, either by cultivation or underworld importation.

Marijuana was something new and adventuresome. The angle-wise mobsters were aiming their pitch straight at the most impressionable age group-America’s fresh, post-depression crop of teenagers.

One adolescent gave a picture to an agent of a typical “smoker” in an apartment or “pad”:

“The room was crowded. There were fifty people but it seemed like five hundred. It was like crazy, couples lying all, over the place, a woman was screaming out in the hall, two, fellows were trying to make love to the same girl and this, girl was screaming and crying and not making any sense. Her clothes were mostly pulled off and she was snickering and blubbering and trying to push these two guys away…. The place was nothing but smoke and stink and these funny little noises I could hear but they were way out, that far I could hardly hear them and they were right there in the room, that laughing and crying and the music and all that stuff. It was crazy wild. But I didn’t want to do anything, I didn’t want to sleep with those women or like that. I just wanted to lie down because the room seemed big and Eke a great tremendous crowd like at a ball game or something. . . “

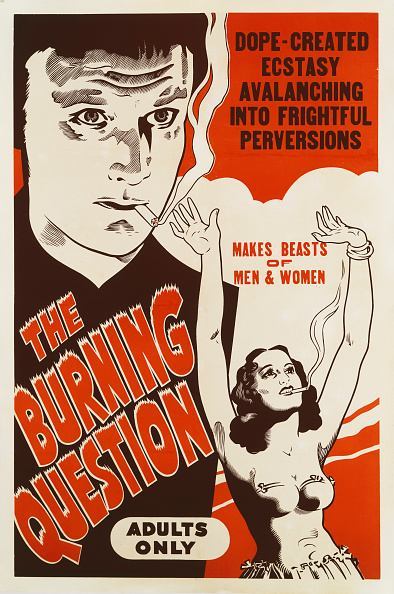

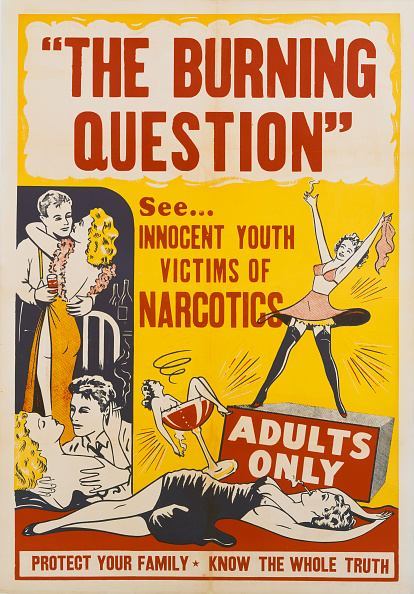

A poster for a US release of Louis J. Gasnier’s 1936-39 propaganda exploitation drama film, ‘The Burning Question’. The film was originaly made as ‘Tell Your Children’ in 1936. It later had extra shots inserted by filmmaker Dwain Esper, who released it under various titles, ‘Reefer Madness’, ‘Dope Addict’, ‘Doped Youth’, and ‘Love Madness’. ‘The Burning Question’ was the title used in the Pennsylvania/West Virginia territory in 1940. (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

…

Marijuana effects on the average user are described in a brochure we published in the Bureau for the information of lay groups. “The toxic effect produced by the active narcotic principle of Cannabis sativa, hemp, or marijuana,” the report states, “appear to be exclusively to the higher nerve centers. The drug produces first an exhaltation with a feeling of well being, a happy, jovial mood, usually; an increased feeling of physical strength and power, and a general euphoria is experienced. Accompanying this exaltation is a stimulation of the imagination followed by a more or less delirious state characterized by vivid kaleidoscopic visions, sometimes of a pleasing sensual kind, but occasionally of a gruesome nature. Accompanying this delirious state is a remarkable loss in spatial and time relations; persons and things in the environment look small; time is indeterminable; seconds seem like minutes and hours like days.

“Those who are accustomed to habitual use of the drug are said eventually to develop a delirious rage after its administration during which they are temporarily, at least, irresponsible and prone to commit violent crimes. The prolonged use of this narcotic is said to produce mental deterioration.”

…

Much of the most irrational juvenile violence and that has written a new chapter of shame and tragedy is traceable directly to this hemp intoxication. A gang of boys tear the clothes from two school girls and rape the screaming girls, one boy after the other. A sixteen-year-old kills his en tire family of five in Florida, a man in Minnesota puts a bullet through the head of a stranger on the road; in Colorado husband tries to shoot his wife, kills her grandmother instead and then kills himself. Every one of these crimes had been proceeded (sic) by the smoking of one or more marijuana “reefers.” As the marijuana situation grew worse, I knew action had to be taken to get the proper legislation passed. By 1937 under my direction, the Bureau launched two important steps First, a legislative plan to seek from Congress a new law that would place marijuana and its distribution directly under federal control. Second, on radio and at major forums, such that presented annually by the New York Herald Tribune, I told the story of this evil weed of the fields and river beds and roadsides. I wrote articles for magazines; our agents gave hundreds of lectures to parents, educators, social and civic leaders. In network broadcasts I reported on the growing list of crimes, including murder and rape. I described the nature of marijuana and its close kinship to hashish. I continued to hammer at the facts.

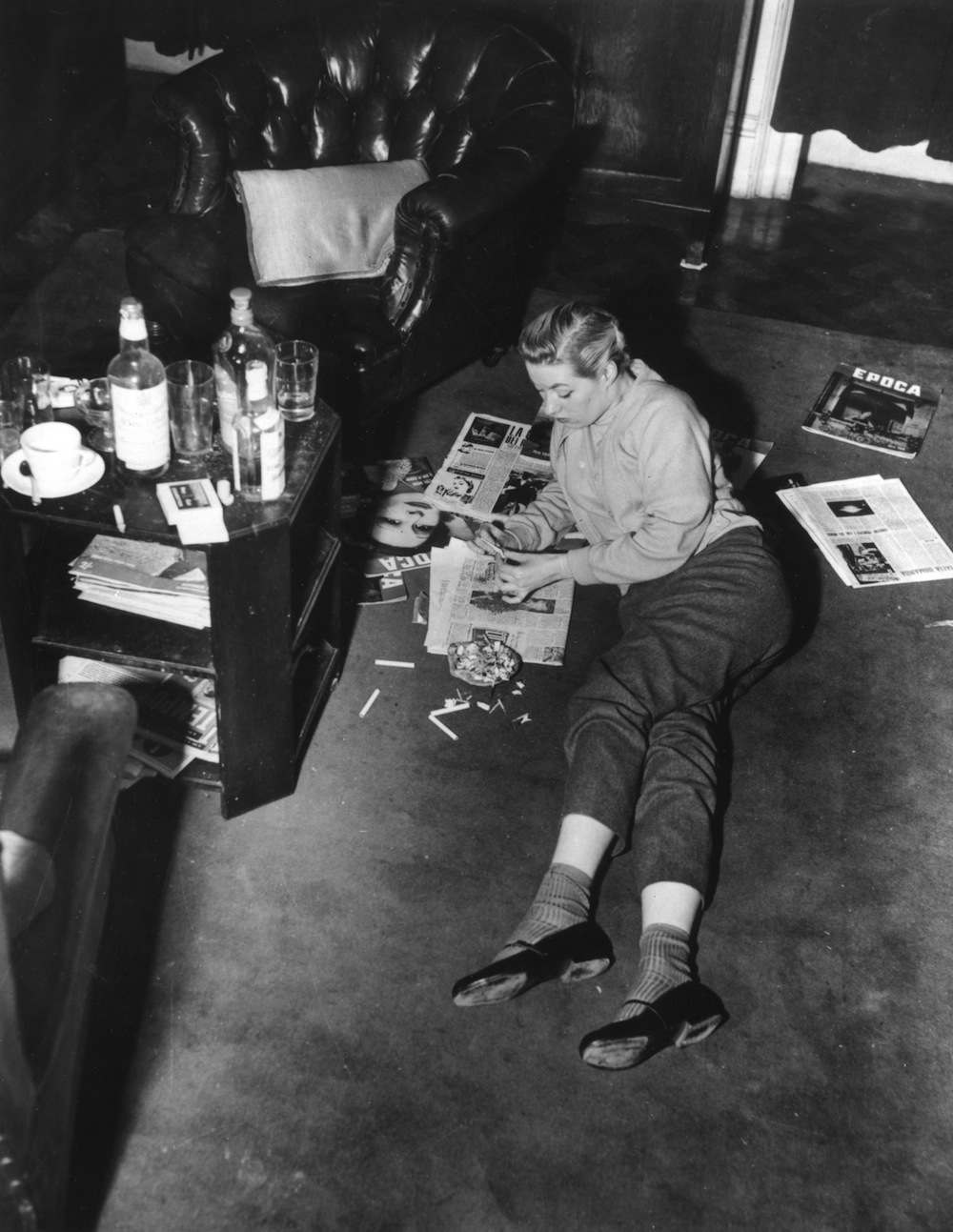

circa 1950: Commercial artist Christine Vasey rolls a ‘joint’, a hand-rolled cigarette containing marijuana. (Photo by Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

…

The 1937 law does not prohibit the sale of marijuana b utputs a tax of $100.00 an ounce on any sale or transfer of drug and makes such sale or transfer illegal without proper registration and approval from the Bureau. Possession without proper authorization can bring a prison term.

The Marijuana Tax Act is patterned in general after the Harrison Act, but with some major technical variations, principally based on the fact that while marijuana is used in laboratory tests it is not used for medical purposes.

There were still some WPA gangs working in those days and we put them to good use. just outside the nation’s capital, for some sixty miles along the Potomac River, on both banks, marijuana was growing in profusion; it had been planted there originally by early settlers who made their own hemp and cloth. The workers cleaned out tremendous river bank crops, destroying plants, seeds and roots. AR through the Midwest also, WPA workers were used for this clean-up job. The. wild hemp was rooted out of America.

During the Second World War, after Axis powers in the Far East and Europe cut off our access to countries where hemp was grown for the making of cord and cloth, we developed, under strict controls, our own hemp growing program on the rich farmlands of Minnesota. Less than one thousandth of one percent was ever diverted into illegal channels. After the war this production stopped and the fields went back to ,corn and wheat. With the war’s end, however, the narcotic branch of the underworld was given a new lift by the publication of an extraordinary document which has come to be known as the La Guardia Report.

The title was a misnomer, it was actually a report of a committee on marijuana which had been appointed by the “Little Flower” of New York to give an objective picture of marijuana from a scientific point of view. La Guardia was always not only an honest official who warred against the syndicate “tin horns,” as he called them, but was also a good friend of Bureau of Narcotics. In Congress he fought consistently for increases for our Bureau to help us to achieve the power needed to do our job.

The men who issued this document were men of science doctors, technicians, authorities Published as a book by the Jacques Cattell Press in 1945, the report bore the tide: The Marijuana Problem in the City of New York: Sociologic Medical, Psychological and Pharmacological Studies, by the Mayor’s Committee on Marijuana.

This report declared, in effect, that those who had been denouncing marijuana as dangerous, including myself and experts in the Bureau, were not only in error, but were spreading baseless fears about the effects of smoking Cannabis. I say the report was a government printed invitation to youth and adults-above all to teenagers-to go ahead and smoke all the reefers they felt like.

Relying solely on a series of experiments with a group of 77 prisoners who volunteered to make the tests, the Mayor’s experts asserted that they found no major menace in the use of this narcotic, which they termed “a mild drug smoked by bored people for the sake of conviviality.”

The report further claimed that there was “no apparent” connection between “the weed” and crimes of violence, that smoking it did not produce aggressiveness or belligerence as a rule, that it could be used for a number of years without causing serious mental or physical harm and that while it might be habit forming it could be given up abruptly without causing distress; in other words, it did not produce the bodily dependence found in heroin, cocaine, morphine and other drugs.

Finally, the report suggested that the drug is so mild that it might well be used successfully as a substitute in the process of curing addiction to other drugs, or even in the treatment of chronic alcoholism.

circa 1955: A drug user buying ready-rolled marijuana cigarettes from a dealer at her door. (Photo by Vecchio/Three Lions/Getty Images)

Doctors and other authorities who studied the effects of this drug, however, tore the report apart for its inaccuracies and misleading conclusions. The Journal of the American Medical Association joined the. Bureau in condemning it as unscientific.

“For many years medical scientists have considered Cannabis a dangerous drug,” the Journal’s editorial of April 26, 1945 stated. “Nevertheless. . . . the Mayor’s Committee on Marijuana submits an analysis by seventeen doctors of tests on 77 prisoners and, on this narrow and thoroughly unscientific foundation, draws sweeping and inadequate conclusions which minimize the harmlessness of marijuana. Already the book has done harm. One investigator has described some tearful parents who brought their 16-year-old boy to a physician after he had been detected in the act of smoking marijuana. . . . The boy said he had read an account of the La Guardia committee report and this was his justification for using marijuana..

A criminal lawyer for marijuana drug peddlers has already used the La Guardia report as a basis to have defendants set free by the Court.

“The value of the conclusions,” continued the editorial, “is destroyed by the fact that the experiments were conducted on 77 confined criminals. Prisoners were obliged to be content with the quantities of drug administered. Antisocial behavior could not have been noticed, as they were prisoners. At liberty some of them would have given free rein to their inclinations and would probably not have stopped at the dose producing ‘the pleasurable principle. . . .’ Public officials will do well to disregard this unscientific, uncritical study, and continue to regard marijuana as a menace where it is purveyed,” the Journal concluded.

There can be no doubt of the damage done by the report. Syndicate lawyers and spokesmen leaped upon its giddy sociology and medical mumbo-jumbo, cited it in court cases, tried to spread the idea that the report had brought marijuana back into the folds of good society with a full pardon and a slap on the back front the medical profession.

The lies continued to spread. They cropped up on panel discussions, in public addresses by seemingly informed individuals. They helped once again, in a new and profitable direction, to bewilder the public and make it unsure of its own judgments. This carefully nurtured public doubt was to pay off with extra millions in the pockets of the hoods. One killer who helped to nourish that doubt-a hoodlum called Lepke took a multi-million-dollar cut in exchange for the terror inspired by the mere mention of his name. – Via Cliff Shaffer’s Drug Library.

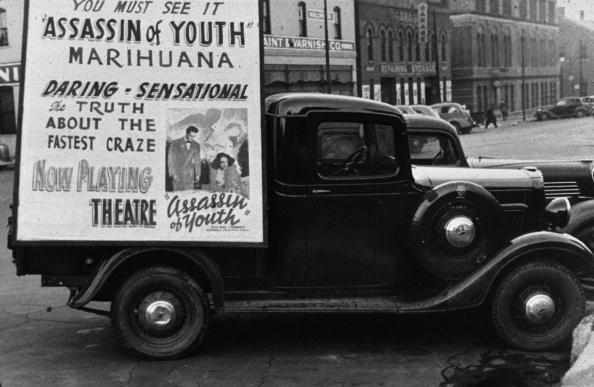

November 1938: A truck in Omaha, Nebraska, carrying a poster advertising ‘Assassin of Youth’, a film warning of the dangers of marijuana. (Photo by John Vachon/Library Of Congress/Getty Images)

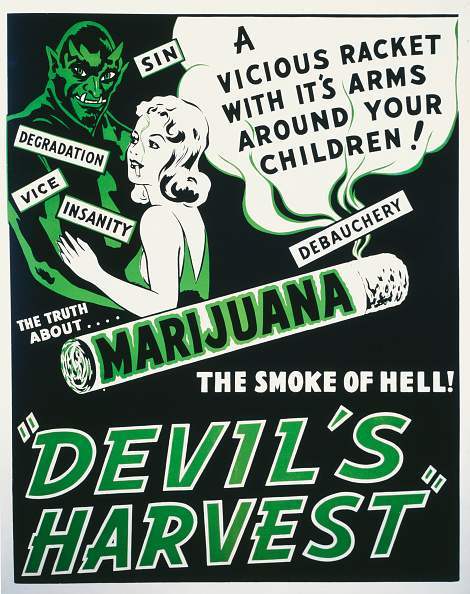

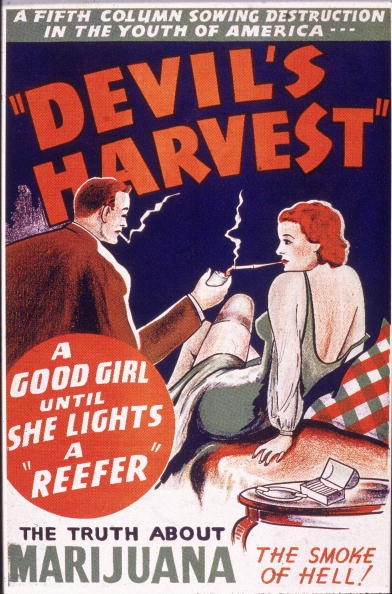

Promotional poster for the film, ‘Devil’s Harvest,’ an exploitation film directed by Ray Test depicting the evils of smoking marijuana, 1942. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

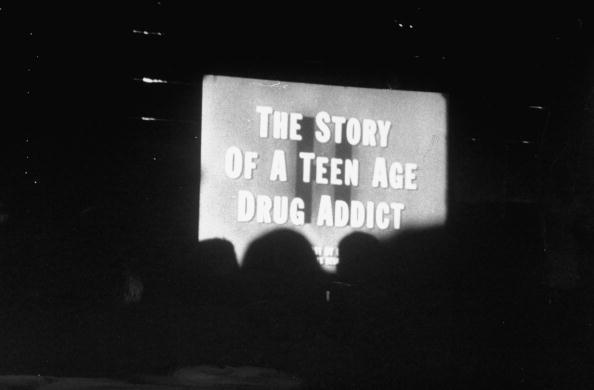

This PSA is from the 1950s. Marty is troubled:

As ever, children needed adult protection from degredation, vice and insanity.

A poster for Ray Test’s 1942 drama ‘Devil’s Harvest’. (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

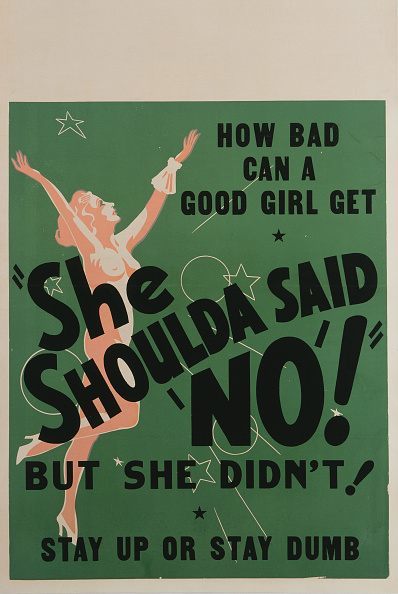

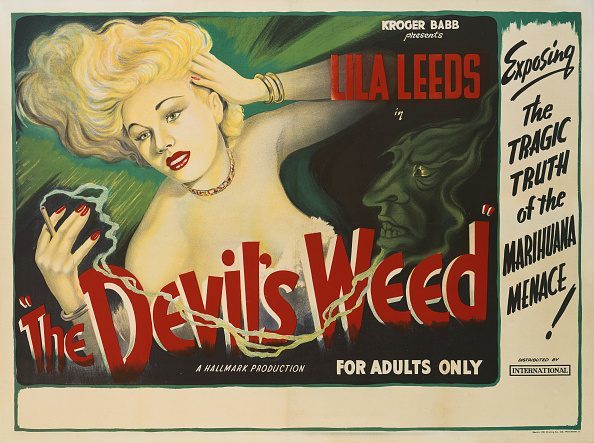

A poster for Sam Newfield’s 1949 drama ‘Wild Weed’ starring Lila Leeds. (Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

A poster for the British release of Sam Newfield’s 1949 exploitation film, ‘The Devil’s Weed’, starring Lila Leeds. The film’s alternative titles are: ‘She Shoulda Said ‘No!’, ‘Marijuana, the Devil’s Weed’, and ‘The Story of Lila Leeds and Her Expose of the Marijuana Racket’.

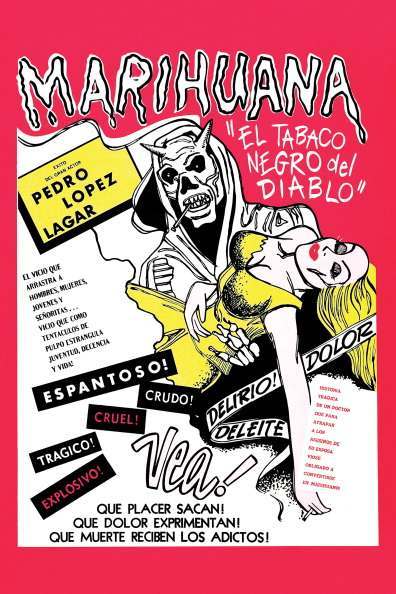

A movie poster, ‘El Tobaco Negro del Diablo’ from Argentina for a Spanish film about a respected surgeon, Pablo Urioste is forced to experience a nightmarish world after his wife, a marijuana addict, dies at a Buenos Aires nightclub, 1950. (Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

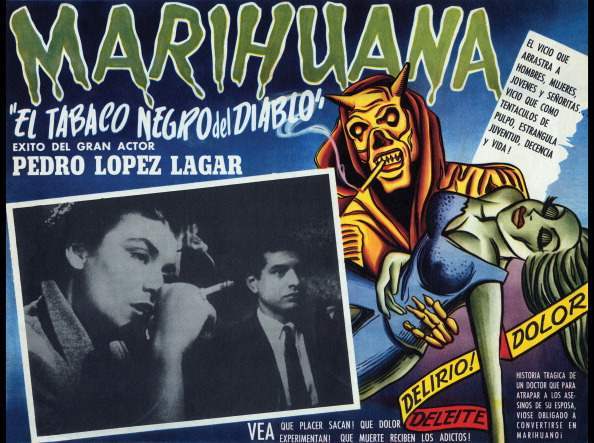

A film lobby card, ‘El Tobaco Negro del Diablo’ from Argentina for a Spanish film about a respected surgeon, Pablo Urioste is forced to experience a nightmarish world after his wife, a marijuana addict, dies at a Buenos Aires nightclub, 1950. (Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

Let’s now consider the library.

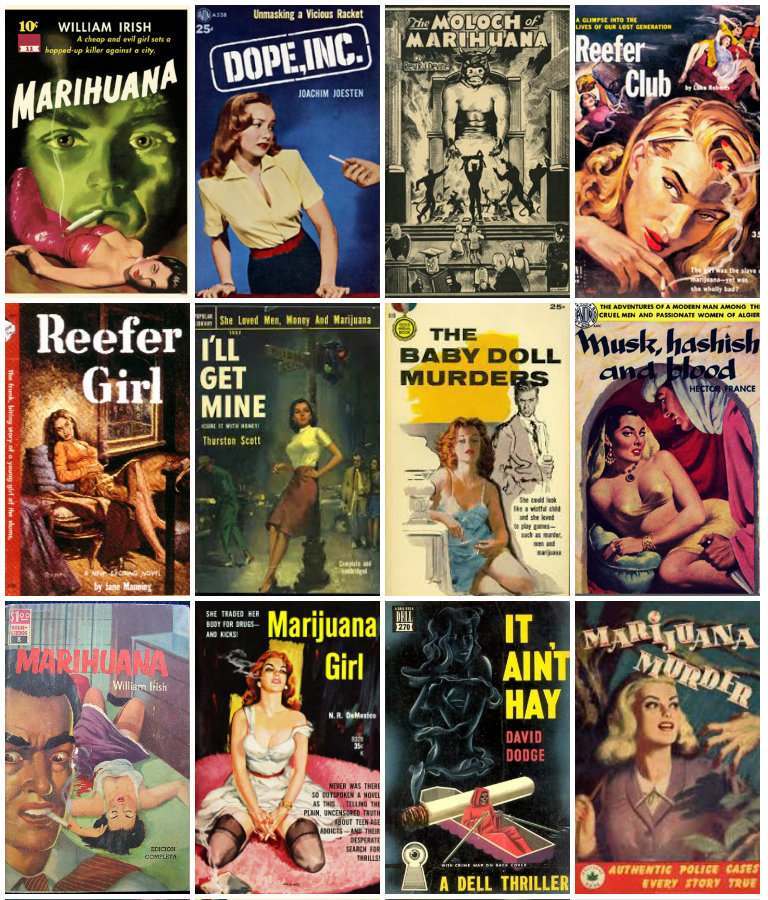

The Herb Museum flicks thoght the pulp:

It Ain’t Hay

A Dell thriller by David Dodge, cover art by Gerald Gregg, first published by Simon and Schuster in 1946. Back cover line: “Where marijuana and murder make a thrilling story.” Hay, another nickname for marijuana, features in this book about dope smuggling. Favorite quote: “Marijuana doesn’t do anything to the inner man except undress him.”Musk, Hashish, and Blood

An avon book by Hector France, cover artist unknown, first published in the ’20’s. This edition 1951. Front cover line:”The adventures of a modern man among the cruel men and passionate women of Algiers.” Enough said.Marihuana

A Dell book by William Irish, cover art by Bill Fleming. this edition 1951. The most famous of the anti-dope genre, this book features Mr. King Turner, who gets stoned and goes on a killing rampage. Cornell Hopley Woolrich (aka William Irish) was a well-known crime novelist whose work includes Night Has a Thousand Eyes and The Bride Wore Black. The striking cover is often copied and remains a valuable collectible today.Dope, Inc.

An Avon book by Joachim Joesten, cover art by Owen Kampen. Published in 1953. This is a non-fiction book supposedly telling you the “facts” about marijuana. However, with phrases that include “hasish-crazed Orientals,” “invariably leads to epilepsy and insanity,” and “medical uses are extremely slight and often non-existent,” the book reads more like bad fiction.

Here’s a final treat for you with time on your hands. Tell your kids. Tell the police. Tell everyone before the Devil takes over:

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.