Guy Burgess woke up in his untidy, musty-smelling bedroom at around 9.30 on the morning of Friday, 25 May 1951. Next to his bed was an overflowing ashtray and lying on the floor was a half-read Jane Austen novel. Since his return from Washington DC three weeks previously, where he had been second secretary at the British embassy, he’d been rising later and later. Burgess had left America in disgrace, and at the British Ambassador’s behest, after several embarrassing drunken incidents. They included being caught speeding at 80 mph three times in just one hour, pouring a plate of prawns into his jacket pocket (and leaving them there for a week), continually chewing raw garlic like others would chew mints, and being loudly vocal, not only with his anti-American views but also about his homosexuality. The FBI later described him, not inaccurately, as ‘a louche, foul-mouthed gay with a penchant for seducing hitchhikers.’ Thoroughly disliked by most of the Americans with whom he came in contact, Burgess behaved as if he wanted to be sent back to England. Many people thought he did.

Burgess was born in Devon in 1911, the elder son of naval Commander Malcolm Kingsford de Moncy Burgess and his wife, Evelyn Mary. Although he was just thirteen when his father died, his mother was affluent enough to send him to Eton. Burgess won an open scholarship to read modern history at Trinity College and he soon joined the Cambridge University Socialist Society. More importantly he also became a member of The Apostles (a secret and elite debating society). It was there that Burgess was introduced to Kim Philby by Maurice Dobb, a communist don and fellow member.

After graduating in 1933, he held a two-year teaching position and in May 1934 Burgess met Arnold Deutsch, a Comintern officer and recruiter for Soviet Intelligence, and would later that year travel to the Soviet Union. Around this time Kim Philby asked him to suggest other recruits, and Burgess suggested Anthony Blunt and Donald Maclean. This was the beginning of the Cambridge network of Soviet agents. As a cover for his Soviet Union support Burgess openly renounced communism and also joined the rather Nazi-friendly Anglo-German Fellowship.

After leaving Cambridge, where he was more often than not described as ‘brilliant’ and ‘charming’, Burgess briefly went to work at The Times but in October of that year found himself a prestigious job at the BBC as a ‘Talks’ producer. He was helped by a reference from the renowned historian Sir George Trevelyan, who wrote: ‘He is a first-rate man. He has passed through the communist measles that so many of our clever young men go through and is well out of it.’

While working for the broadcaster he got into trouble for abusing his expenses and when defending his exorbitant claims to his superiors, Burgess wrote: ‘I normally travel first class and see no reason why I should alter my practice when on BBC business, particularly when I am in my best clothes’. Either his cover as a Soviet spy was particularly sophisticated, or more likely, despite his communist sympathies, Burgess had always been a snob. When the police raided a drinking club one night during the war, he was purported to have said: ‘I’m Guy Burgess and I live in Mayfair. I presume you, Inspector, to come from some dreary little suburb.’

Towards the end of the war in 1944 he moved to the News Department of the Foreign Office and soon took on the position of secretary to the British Deputy Foreign Minister, Hector McNeil. The job gave him access to hundreds of top secret Foreign Office documents which he happily photographed for the KGB on a regular basis. This continued until 1947 when he was sent to the Washington DC British embassy as Second Secretary.

Four years later and now back in London, Burgess was living in a small three-roomed flat in Mayfair situated at Clifford Chambers, 10 New Bond Street and opposite Asprey the famous jewellers. The location was (and is of course) a particularly salubrious part of London and a long, long way from the Soviet Union and anything it represented. Burgess, the Soviet spy from such a privileged background, coped with this irony with surprising ease. At least until this particular Friday morning in 1951 when his world suddenly turned upside down.

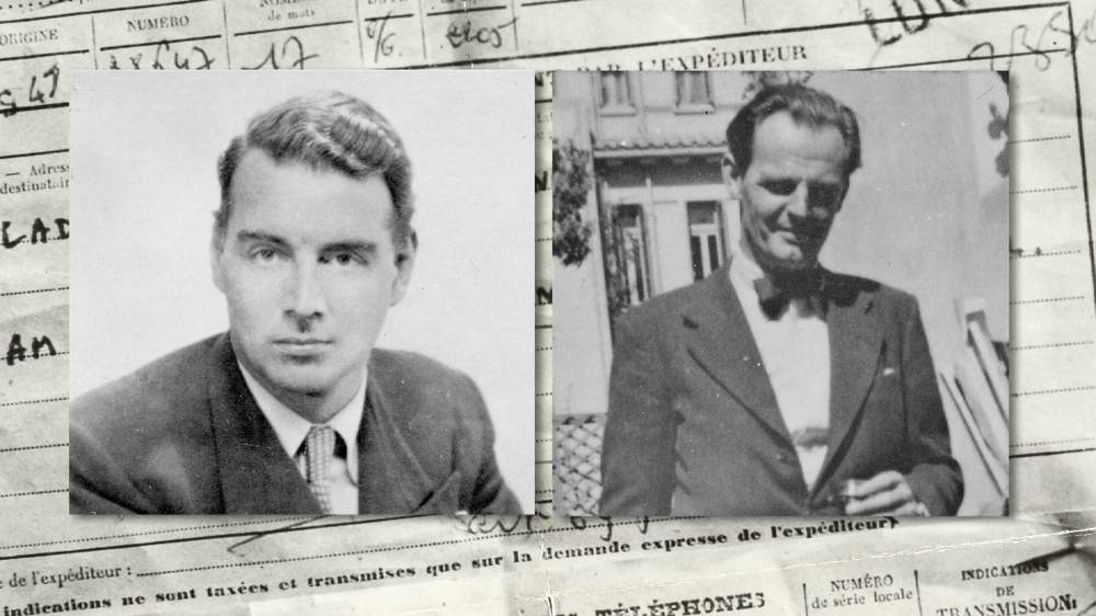

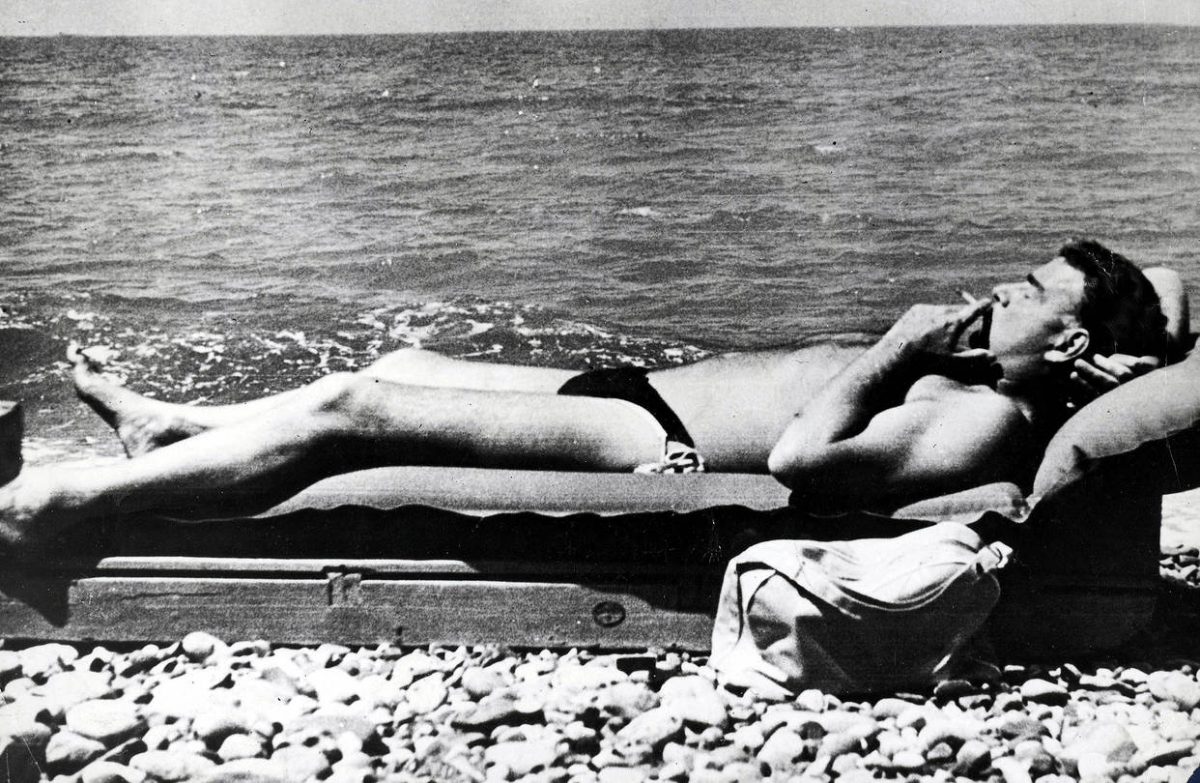

Jack Hewit, Guy Burgess’s former lover at the flat they shared at Clifford Chambers in Mayfair, 1951.

Not long after he had woken in his untidy bedroom, Burgess had been brought a cup of tea by his flatmate Jack Hewit, known to his friends as ‘Jackie’. Son of a metal worker, Hewit had won a scholarship to ballet school, but his father forbade him to accept it, so he ran away from home and began dancing in revues. He met Guy Burgess while dancing in the chorus of a revival of the musical comedy No, No, Nanette and subsequently became Burgess’s lover. Years later the two were still very close friends and had been sharing various flats in and around Mayfair for fourteen years. Hewit later wrote of that morning: ‘Guy lay back, reading a book and smoking, and he seemed normal and unworried. When I left the flat to go to my office, Guy said: “See you later, Mop” – that was his pet name for me. We intended to have a drink together that evening.’

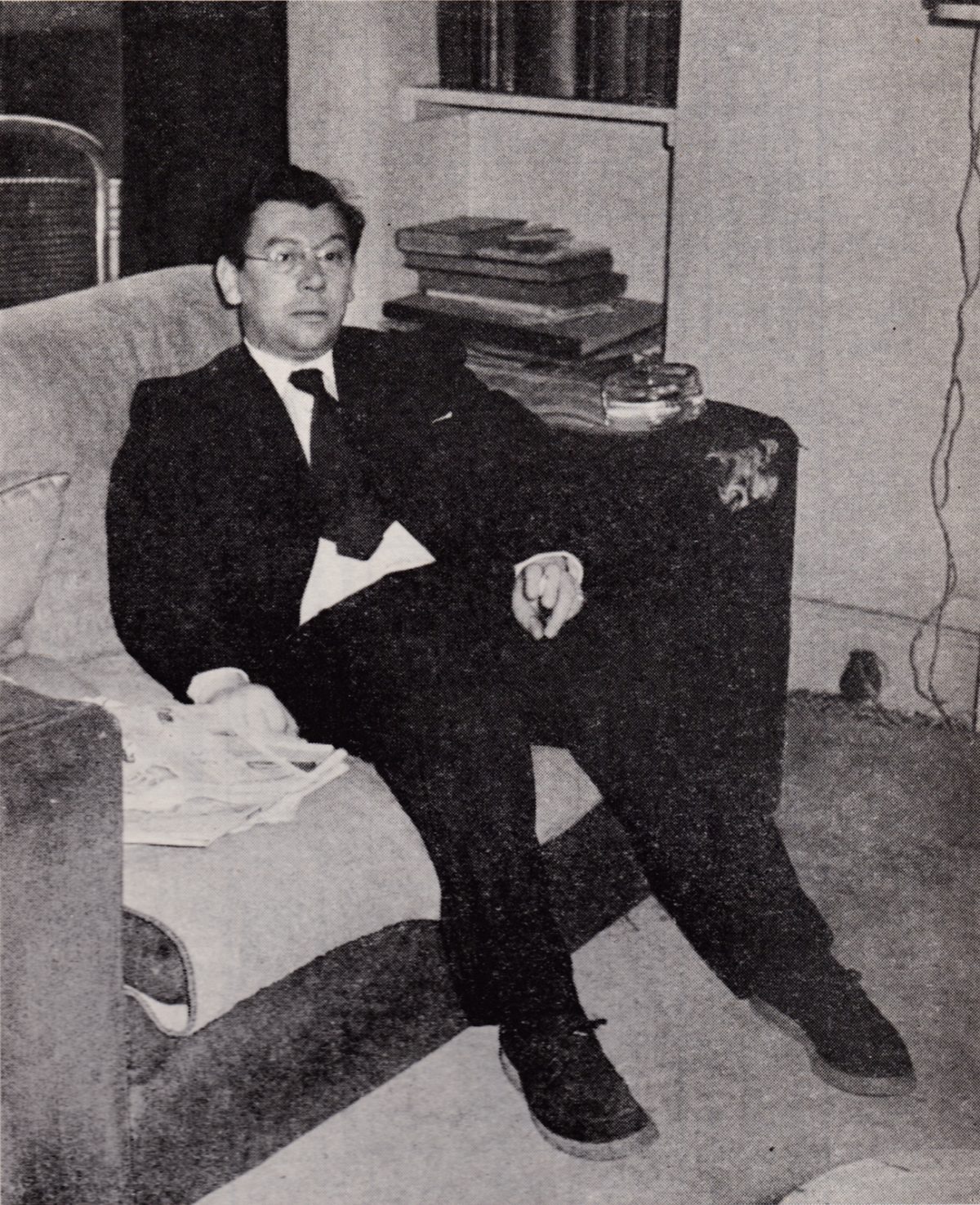

As Burgess was waking up, Donald Duart Maclean was already sitting at his desk in Whitehall having caught his usual train from Sevenoaks some two hours previously. Maclean was the son of one of the most illustrious Liberal families in the country. His father, Sir Donald Maclean, had first entered Parliament as the Liberal member for Bath in 1906 and had been President of the Board of Education in the cabinet when he died in 1932. Nineteen years later Donald Maclean was head of the American department at the Foreign Office in King Charles Street. The job sounded important but care was already being made by the authorities that it should be of no operational significance. For several weeks now, along with three other men, Maclean had been under suspicion for leaking atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. In the last few days, however, the four suspects had become just one. Two years younger than Burgess, Maclean was exactly 38 years old, for it was his birthday and he had already asked if he could take the next morning as leave (Saturday mornings were still worked by many civil-servants in the 1950s) so that he could celebrate the whole weekend with family and friends at home in Surrey.

The British diplomat and spy Donald Duart MACLEAN with his wife Melinda MARLING and his two sons Ronald and Fergus in the 50’s.

Around 10-10.30 that morning, Herbert Morrison, who had recently become Foreign Secretary, was visited in his office by a senior MI5 officer and the head of Foreign Office security in his office. After receiving and reading a few official papers, Morrison signed one of them. It gave MI5 permission to question Donald Maclean about links with the Soviet Union. The interrogation was to begin on Monday 28 May (not even a Soviet mole in the upper echelons of the Foreign Office justified ruining a perfectly good weekend). By now both Maclean and Burgess knew something was wrong and a few days previously had met for lunch to discuss the matter.

Initially intending to eat at the Reform Club on Pall Mall, where Burgess was a member, they found the dining room full and walked to the nearby Royal Automobile Club instead. Ostensibly they were meeting about a memorandum that Burgess had been preparing about the threat of McCarthyism and American policy in the Far East, but on the way Maclean said: ‘I’m in frightful trouble. I’m being followed by the dicks’. He pointed out two men standing by the corner of the Carlton Club. Burgess later described the two men: ‘There they were, jingling their coins in a policeman-like manner and looking embarrassed at having to follow a member of the upper classes.’

Just three years previously Maclean had been posted to Cairo as one of Britain’s promising young diplomats. He started drinking heavily and behaving in a way that couldn’t be ignored by his superiors. At a party given by King Saud he urinated on the carpet and at another, smaller, gathering he was seen arguing furiously with his wife before seemingly trying to strangle her. Maclean was almost certainly either gay or bisexual and this, along with the weight of living two separate lives as a spy, was patently starting to take its toll. His wife Melinda once wrote to her sister saying: ‘Donald is still pretty confused and vague about himself, and his desires, but I think when he gets settled he will find a new security and peace. I hope so … He is still going to R. (the psychiatrist), however, and is definitely better. She is still baffled about the homosexual side which comes out when he’s drunk, and I think slight hostility in general, to women.’ Maclean was advised to take medical leave in May 1950 but after six months the Foreign Office decided, extraordinarily, to make him head of its American Department.

At around the same time as the Herbert Morrison security meeting in Whitehall, Burgess left his flat in New Bond Street. He had just received a telephone call from Western Union relaying a telegraph from Kim Philby in America about a car he had left behind in Washington. In reality it was almost certainly a coded message warning him that Maclean would be interrogated after the weekend. Burgess hurried to the Green Park Hotel on Half Moon Street just off Piccadilly and about ten minutes walk from his flat. The hotel is still there, and with almost the same name (it has Hilton and London preceding it now), but when Burgess walked through the door in 1951 the street would have looked completely different. Although the hotel had survived the worst of the air raids during the war, much of the surrounding area was either a bomb or building site. Still to be rebuilt, in 1940 much of the terrace on the opposite side of the street had been destroyed by a German air raid, as had the entire east corner of the road at the junction with Piccadilly.

In the lobby of the hotel Burgess met a young American student called Bernard Miller whom he had befriended on his journey back from the US on the R.M.S. Queen Mary. Burgess later described the American as, ‘an intelligent progressive sort of chap’. They had coffee in the hotel’s comfortable lounge and then went for a walk in nearby Green Park. They had previously planned a short trip to France and Burgess had already booked two tickets for a boat that sailed that night. They hadn’t been walking long before Burgess suddenly stopped, turned to his surprised American friend who had been animatedly chatting away about their trip, and said: ‘Sorry Bernard, I haven’t been listening, really. You see, a young friend at the Foreign Office is in serious trouble, and I have to help him out of it, somehow.’ Burgess assured the shocked Miller that he would do everything he could to make their midnight channel-ferry but he couldn’t be definite about it until a few hours later. By now it was just before midday and while the American went back to his hotel, Burgess went to the Reform Club for a large whisky. After half an hour he asked the Porter to call Welbeck 3991 and ordered a hire-car for ten days. He also tried to call his friend Goronwy Rees but only got through to his mother. Characteristically, he ‘forgot’ to pay for the call and the amount owing, his name, and the telephone number he called, was written down on a note and pinned up on the members’ noticeboard. It remained there for some time.

G Parmigiani Figlio Ltd on the corner of Old Compton Street and Frith Street, Soho, London, Britain

Corner of Old Compton Street and Frith Street in Soho, London, Britain – 1952

Timothy Behrens, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews at Wheeler’s, Old Compton Street, 1963, photo by John Deakin

While a worried and thoughtful Burgess was slumped in a large corner armchair at his club, Maclean left his office and walked up Whitehall and across Trafalgar Square to Old Compton Street in Soho. There he met a couple of friends for lunch at Wheeler’s, which in 1951 had only been in existence for just over twenty years but was already a Soho institution. The owner Bernard Walsh, a large and friendly Whitstable man, had started it in 1929 as a small retail oyster shop. He noticed how popular his oysters were in London’s top restaurants so he bought a few tables and chairs and started serving them himself. He soon built a bar for the customers and before long Wheeler’s was a full-blown restaurant. The war, despite much of Old Compton Street having been badly bombed, only made Wheeler’s more successful. Oysters weren’t rationed and it was easy for Walsh to sell them below the five-shilling limit on the cost of a meal imposed by government Second World War restrictions.

By 1951, when Maclean and his friends visited for lunch, the restaurant featured a long counter on the left-hand side where a waiter or Walsh himself opened oysters at a frightening speed – up to six hundred an hour if the restaurant was busy. The back area had its own small bar and claret coloured couches where the menu could be perused before sitting in the restaurant proper. The large green menu contained thirty-two sole and lobster dishes but no vegetables, save for a few boiled potatoes, and no desserts. During post-war austerity, when English food was at its dreariest and some of it still rationed, the meals served at Wheeler’s seemed luxurious. Maclean and his friends stood at the busy bar and ordered a dozen oysters and some Chablis. Maclean seemed in good spirits and if the 38 year old had something on his mind he wasn’t showing it. Regular customers of Wheeler’s at the time included Lucien Freud and his wife Elizabeth Blackwood, Francis Bacon, the writers Colin MacInnes and Cyril Connolly and countless other Soho artists, intellectuals and drinkers. Perhaps the Daily Express star journalist and broadcaster Nancy Spain was there that lunchtime. She often was during 1951 and from time to time was accompanied by the writer Elizabeth Jane Howard who occasionally worked for her. Howard once recalled, after one such Wheeler’s lunch, that Spain asked her to go to bed with her: ‘”Oh, come on darling. Just pop into bed with me and let’s see how we feel.” So I did. “Well?” The bright brown bird’s eye was fixed on me. Eventually she said, “Well, it doesn’t seem to be any good. Never mind.” We got out of bed and put on our clothes. And that was that.’

Wheeler’s was too crowded to be comfortable and Maclean decided that they would eat the rest of their lunch elsewhere. He seemed unconcerned and almost nonchalant when he and his friends walked up Greek Street, through Soho Square and on to Charlotte Street. Here they had two further courses at a German restaurant and delicatessen called Schmidt’s, situated at numbers 35-37. In 1951 this area of London was still known to most people as North Soho and the name Fitzrovia, named after the Fitzroy Tavern, would generally not be used for a decade or two. Incidentally, the word ‘Fitzrovia’ was recorded in print for the first time in an article by Tom Driberg, the Labour MP and also close friend of Guy Burgess. Donald Maclean wouldn’t have called it Fitzrovia but he might have jokingly called Charlotte Street ‘Charlottenstrasse’ as the road occasionally was still called at the time. Schmidt’s was the last vestige of the German community which had settled north of Oxford Street in the late nineteenth century. Frederic William Wile, the former Berlin correspondent for the Daily Mail wrote about the restaurant in 1916: ‘Frederick Schmidt’s dining room is a crammed little apartment, not more than twelve or fifteen feet square, containing four marble-topped tables unadorned with tablecloths. It is for all the world like the Kneipen or Destillationen (low-class public houses) with which every street in the cheaper quarters of German towns and cities is infested.’

Most of the staff at Schmidt’s had been interned during both of the world wars and this is often given as an explanation why the waiters were described somewhere between ‘curt’ and ‘the rudest in the world’. Schmidt’s was also known for its cheap prices and this may or may not have been a reason why T. S. Eliot was a regular at the restaurant where, dressed in a navy blue suit, he would eat the Weiner schnitzel with chilled Moselle wine. The writer A.S. Byatt also often visited and described the establishment in her novel Still Life: ‘In Schmidt’s amazing delikatessen you could buy sauerkraut from wooden barrels, black pumpernickel, wurst cooked and uncooked, huge choux pastries and little cups of black coffee. In Schmidt’s you paid for everything with little receipts at a central caisse presided over by an erect moustached lady with a black dress and lace’ Ms Byatt was being kind, the woman behind the till dressed in black was usually described as ‘bearded’. In 1951 the restaurant still served food using an old European restaurant custom where the waiters brought staple middle-European main courses, such as eisbein with sauerkraut or frankfurters with spaetzle, from the kitchen and only then sold them to the customers. By 1976 the local German/Jewish community had long since relocated to Golders Green or Edgware and Schmidt’s had to close down. It lay empty for years. In 2015 a Japanese restaurant called Roka is in the premises.

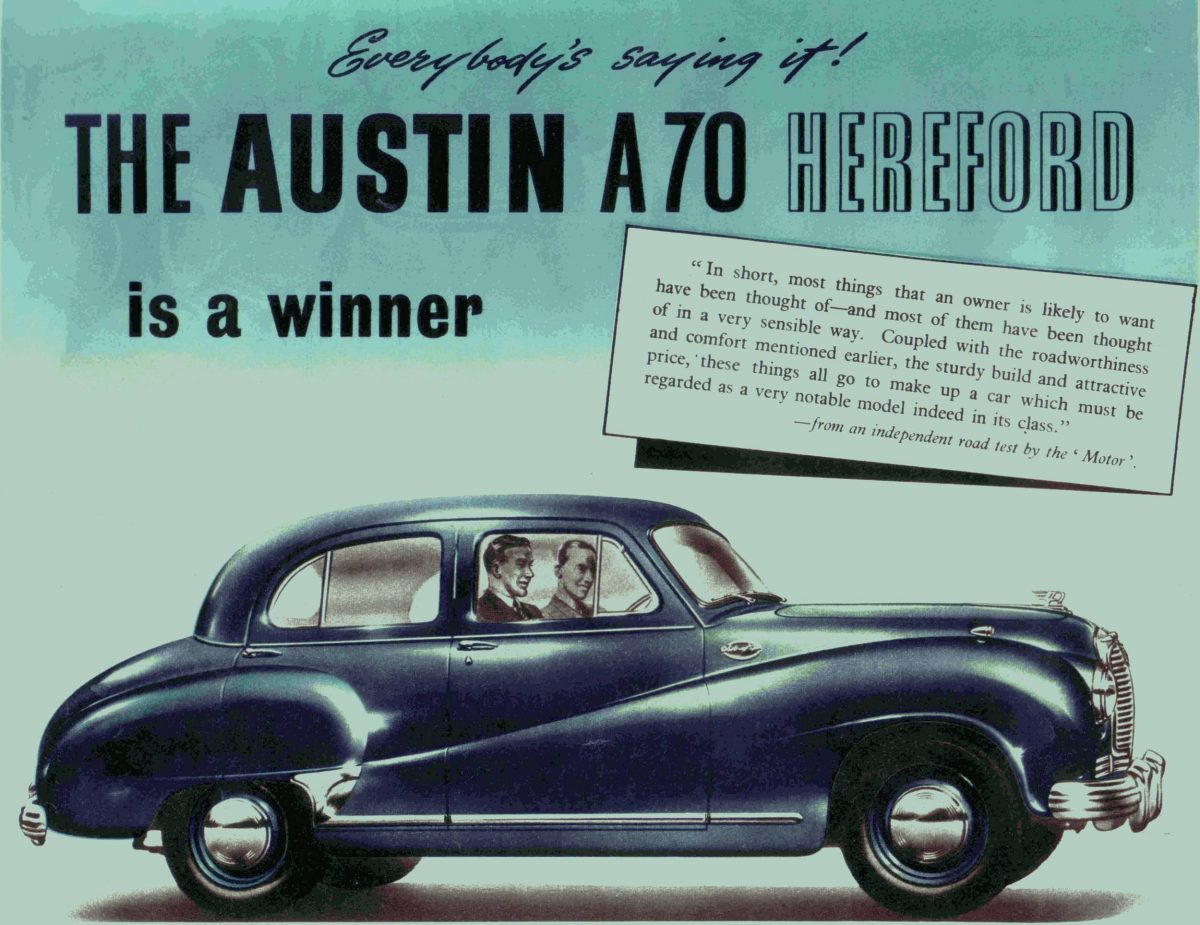

Maclean and his friends had a relatively long, relaxed lunch and, afterwards, while saying goodbye to them he gratefully accepted an offer to stay at their house while his wife was away in hospital having their baby. Melinda Maclean was only two weeks from having their third child and he said he’d call them in the following week to arrange the details. As Maclean was saying goodbye to his friends, Burgess was probably calling on Welbeck Motors at 7-9 Crawford Street, half a mile or so north of Marble Arch, to pick up his hire-car. It was an Austin A70 and was due to be returned on 4th June, ten days later. He paid £25 cash in advance – £15 for the hire of the car and £10 deposit. Burgess drove the Austin down to Mayfair where he parked outside Gieve’s at 27 Old Bond Street at about 3 pm.

The two-hundred-year old tailors had only been at these premises for about ten years. The original flagship store, a few doors down at number 21, had been irreparably damaged by a bomb during the war. Incidentally Gieves and Hawkes, now possibly the most famous bespoke tailoring name in the world, only merged in 1974 when Gieve’s bought out Hawkes, also enabling it to acquire the valuable freehold of No. 1 Savile Row. The acquisition was particularly well timed because not long after the merger, the Gieve’s shop in Old Bond Street was again destroyed by high explosives. This time it was courtesy of the IRA but it meant that from 1975, number 1 Savile Row became Gieve’s and Hawkes. Which is exactly where the illustrious tailoring shop is today. Burgess bought a ‘fibre’ suitcase at Gieve’s and also a white mackintosh. Although very warm and almost 27 degrees, thunder could be heard in the distance and it had started raining heavily. After paying for his purchases Burgess went to meet Bernard Miller again but after a couple of drinks he dropped the young American back at his hotel telling him: ‘I’ll call for you at half-past seven.’ Burgess didn’t call for him and they never saw each other again.

Meanwhile Maclean had taken a taxi down to the Traveller’s Club – the club on Pall Mall that had long been associated with the Foreign Office and the Diplomatic Service. He had two drinks at the bar and cashed a cheque for five pounds. He did this most weekends so nothing appeared unusual. There wasn’t anyone at the club he knew so he walked back to his office just after three. Burgess drove the hired Austin A70 back to his flat where he met Hewit who had by now returned home from work. While they were talking the phone rang. Burgess immediately answered it and made it clear to Hewit that he was talking to Maclean. After the telephone conversation a visibly upset Burgess left the flat almost immediately but not before he grabbed £300 in cash and some saving certificates. He also filled his new suitcase with some clothes and his treasured volume of Jane Austen’s collected novels. He asked to borrow Hewit’s overcoat and then left the flat without properly saying goodbye.

Burgess was next seen back at the Reform Club in Pall Mall where he had a quick drink and asked for a road map of the North of England (probably as a diversion). From there he drove the twenty-two miles to Maclean’s home at Tatsfield in Surrey. While Burgess was on his way Maclean left the Foreign Office at exactly 4.45 pm and walked up Whitehall to Charing Cross Station, where he joined the hurrying commuter crowd. The two MI5 ‘dicks’ were still following him but only as far as the station, where they made sure he got on his usual 5.19 train to Sevenoaks and then they both went home.

The two friends arrived at Maclean’s house within half an hour of each other and Burgess was introduced to Maclean’s wife Melinda, as Mr Roger Styles – a business colleague. Burgess must have been playing with the security services with this name and used two Agatha Christie novels The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and The Mysterious Affair at Styles to make up the alias. They all sat down for a birthday dinner at seven for which Melinda had cooked a special ham for the occasion. After the meal, Maclean put a few things into a briefcase, including a silk dressing gown, and casually told his wife that he and ‘Styles’ would have to go on a business trip and unlikely to be away for more than a day.

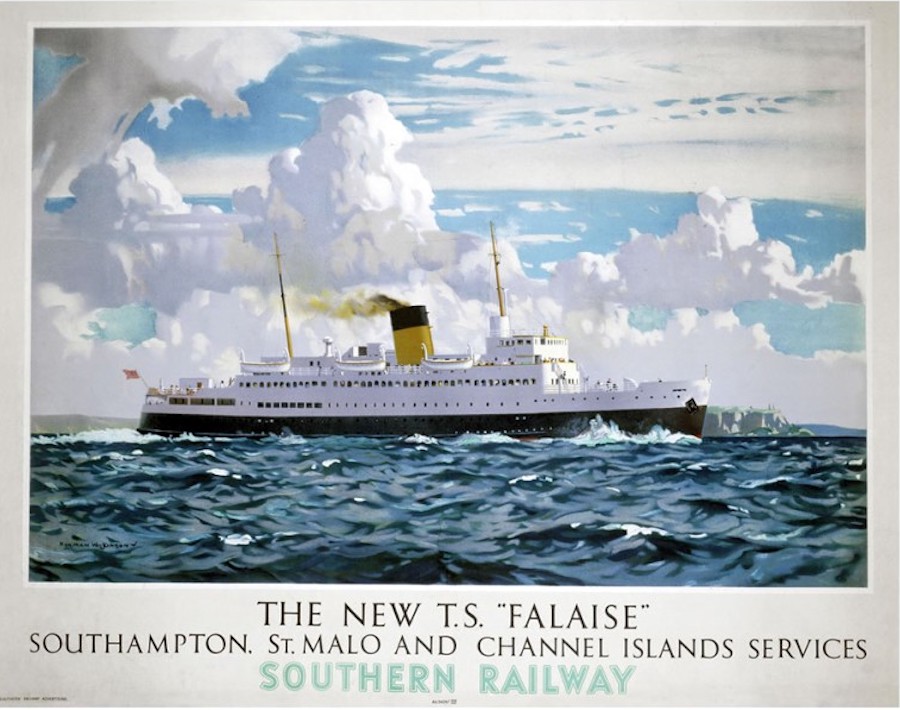

At 9.00 pm with Burgess at the wheel of the cream-coloured Austin A70, they set off on a 100-mile journey to Southampton. The cross-channel ferry ‘Falaise’, for which Burgess had already bought tickets intending to use them for his trip with Bernard Miller, was due to leave for St Malo at midnight. After speedily driving though the deserted streets of Southampton they made it to No. 9 dock with just minutes to spare. In their haste they almost hit a lorry driven by Sid Hampton, an employee at the dockside garage. He described the scene to the press: ‘They roared into the docks just before the ship sailed. The two men jumped out, banged the doors. One of them was carrying two cases, the other man one. I was about to tell them off for speeding in the docks when one of them threw a couple of bob on the ground. He shouted: ‘Buy yourself a drink’. Hampton asked them what they wanted to do with the car they had just left on the quayside. As they ran up the gangway, almost as it was being raised, Burgess yelled back: ‘I’m back on Monday.’

He wasn’t of course, although it’s said that he thought he would be, and Burgess and Maclean never set foot in Britain again. The names Burgess and Maclean will be forever linked but when Goronwy Rees sold his reminiscences of Burgess and Maclean to the Sunday People, Burgess was particularly upset that it was implied that they had been lovers. Burgess had once said: ‘The idea of going to bed with Donald! That great white body, it would be like sleeping with Dame Nellie Melba!’

This post is an excerpt from Rob Baker’s book Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.