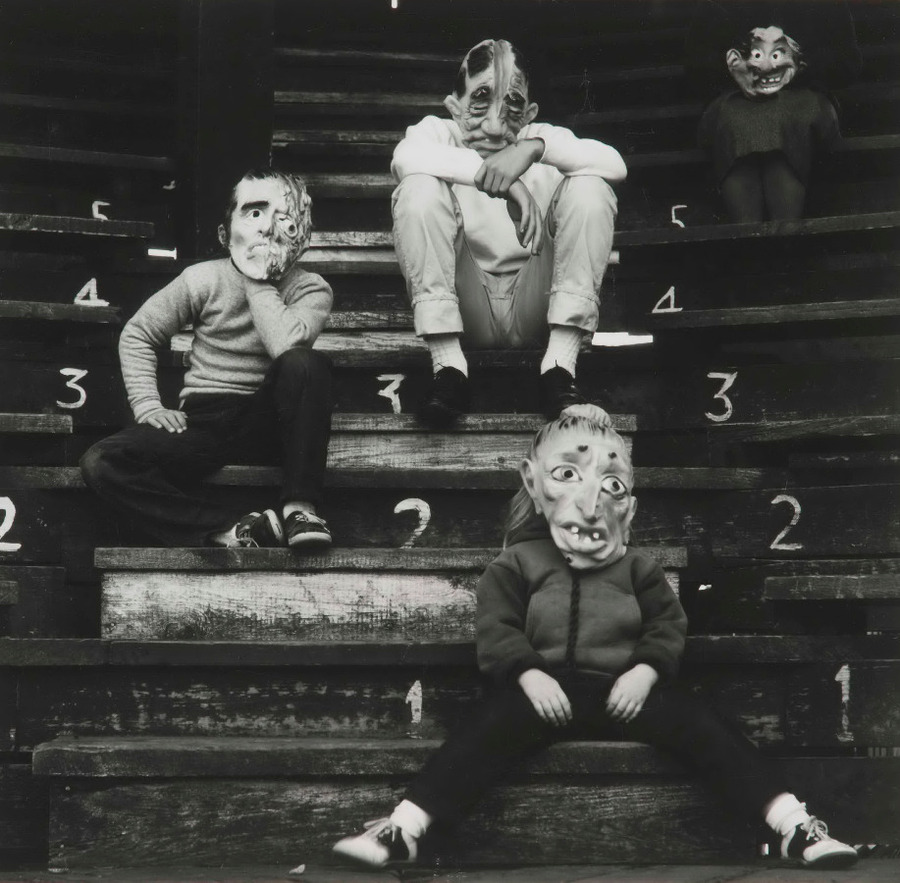

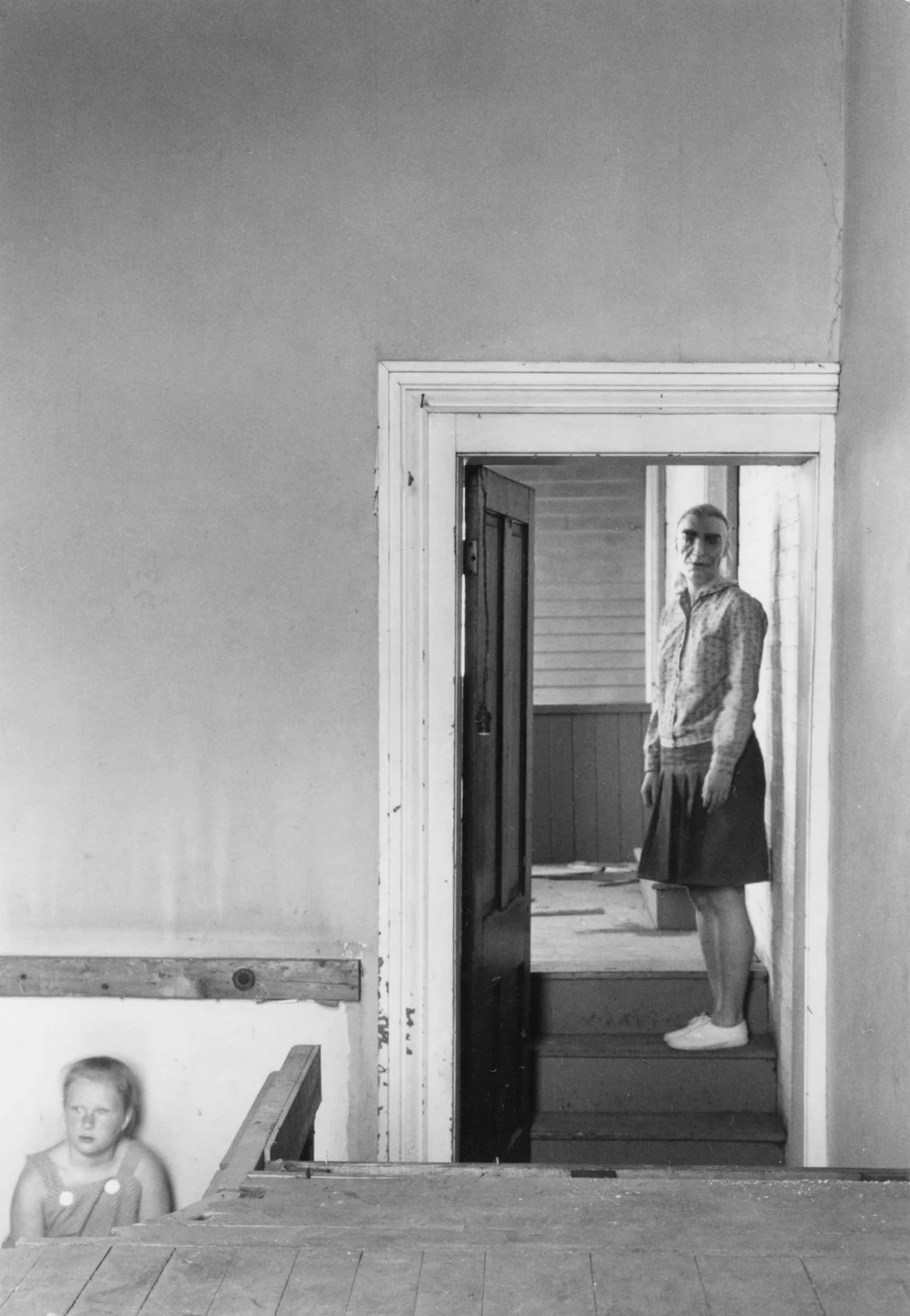

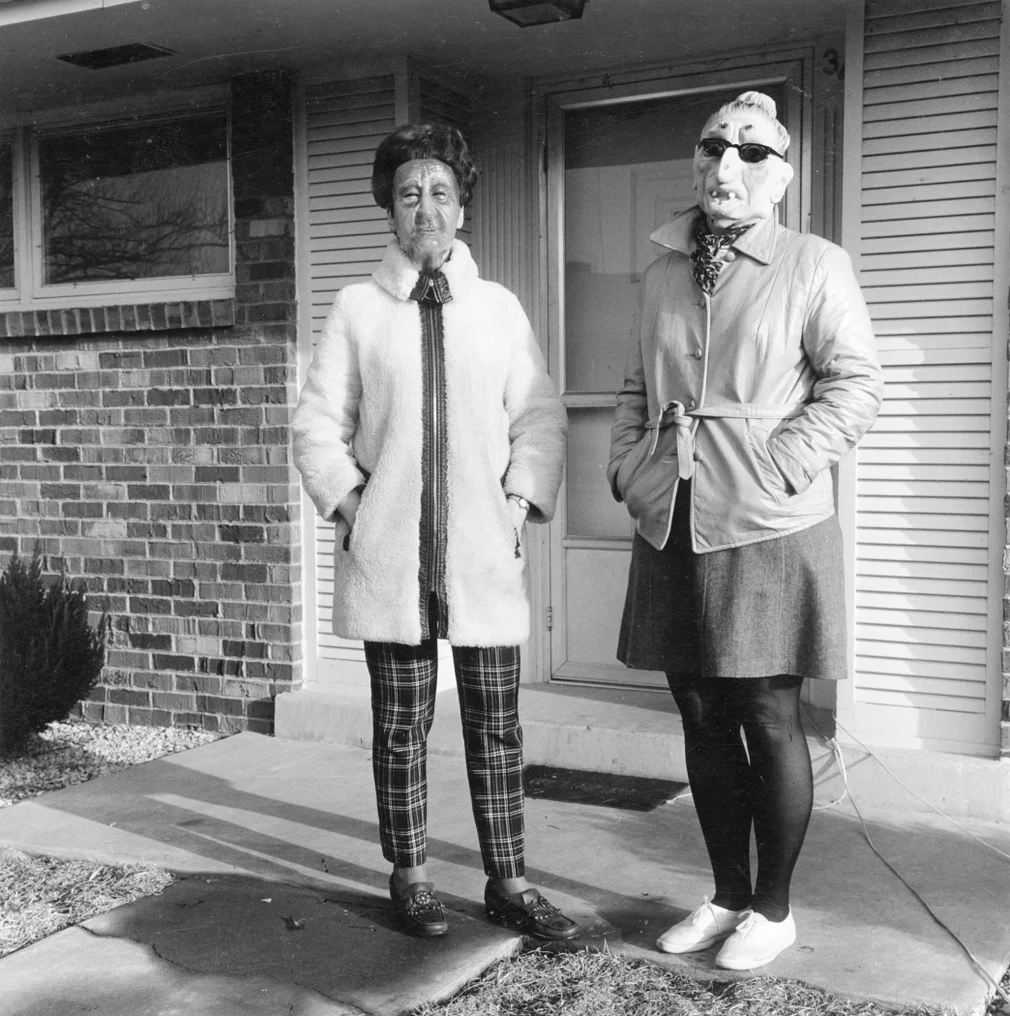

American photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard said that masks erased the differences between people.

One day in 1958 or ’59, professional optician and “dedicated amateur” photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard (May 15, 1925 – May 7, 1972) bought a few dozen masks in a branch of Woolworths in Lexington, Kentucky. “He immediately liked their properties,” said his son Christopher, who was with him at the time. “They were latex and had a very unique odor. In the summer they could be hot and humid.”

A 13-year project began in which Meatyard invited friends and family and friends to wear a mask for a photo. “He picked the environment first,” Christopher told the Smithsonian. “Then he’d look at the particular light in that moment in that place, and start composing scenes using the camera.”

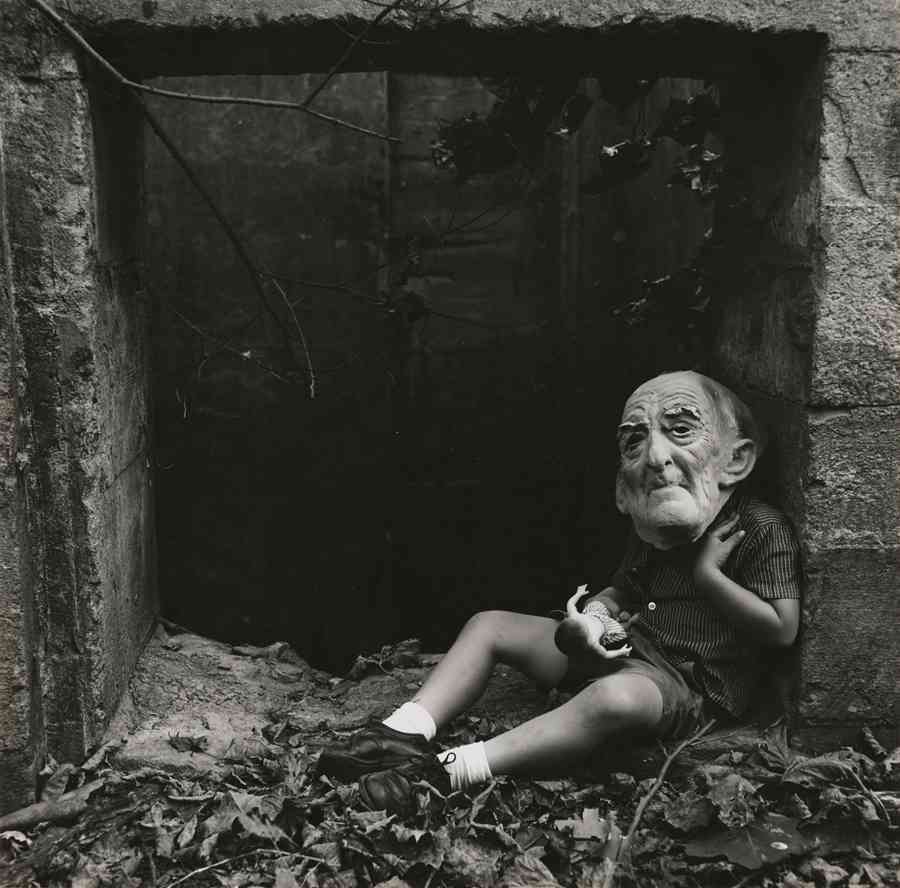

“[in a mask] the idea of a person, a photograph, say, of a young girl with a title ‘Rose Taylor’ or the title ‘Rose’ or no title at all becomes an entirely different thing,. ‘Rose Taylor’ is a specific person, whether you know her nor not. ‘Rose’ is more generalized and could be one of many Roses – many people. No title, it could be anybody.”

– Ralph Eugene Meatyard

“He said he felt like everyone was connected, and when you use the mask, you take away the differences.”

– Mary Browning Johnson, who sat for Meatyard

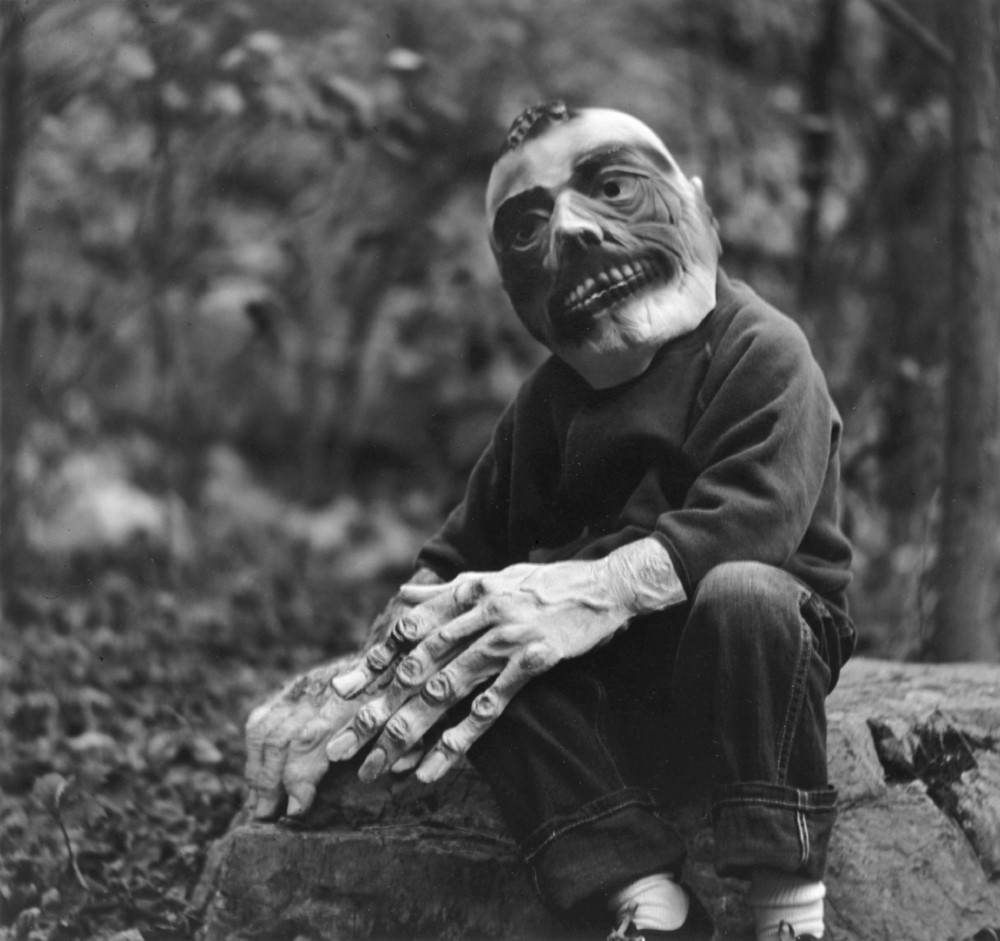

“I realized that even though you have the mask, your body language completely gives you away. It’s as if you’re completely naked, completely revealed.”

– Emmet Gowin, who sat for Meatyard

Meatyard talked about his use of masks and dolls in an interview with the University of Louisville in 1970:

“There’s a number of books by a number of writers on how things are masked and how masks are done. I’ve read some but I haven’t read all of them by any means. All about faces but that sort of thing has never really been an influence on me other than that – the main reason is I’ve used them to make a particular person less particular and more universal. You see, sometimes wherever I want the feeling of a human being– this has a great deal to do with a picture whether you’re making – I’ll take a picture of this wall; it’s one thing and you add a feeling of humanness in it and that makes a lot of difference. You couldn’t put a fish up there and get the same feeling as if you had a doll up there. The feeling of having something that represents life rather than non-life is important in a lot of my pictures.

“I don’t know if you’ve seen any where I’ve used dolls, but I’ve used dolls a number of times in conjunction with masks and instead of, as I said, instead of people and along with people. 01:06:00They do sort of the same sorts of things. I used them in sculptures for the very same reason that they are people and belong.”

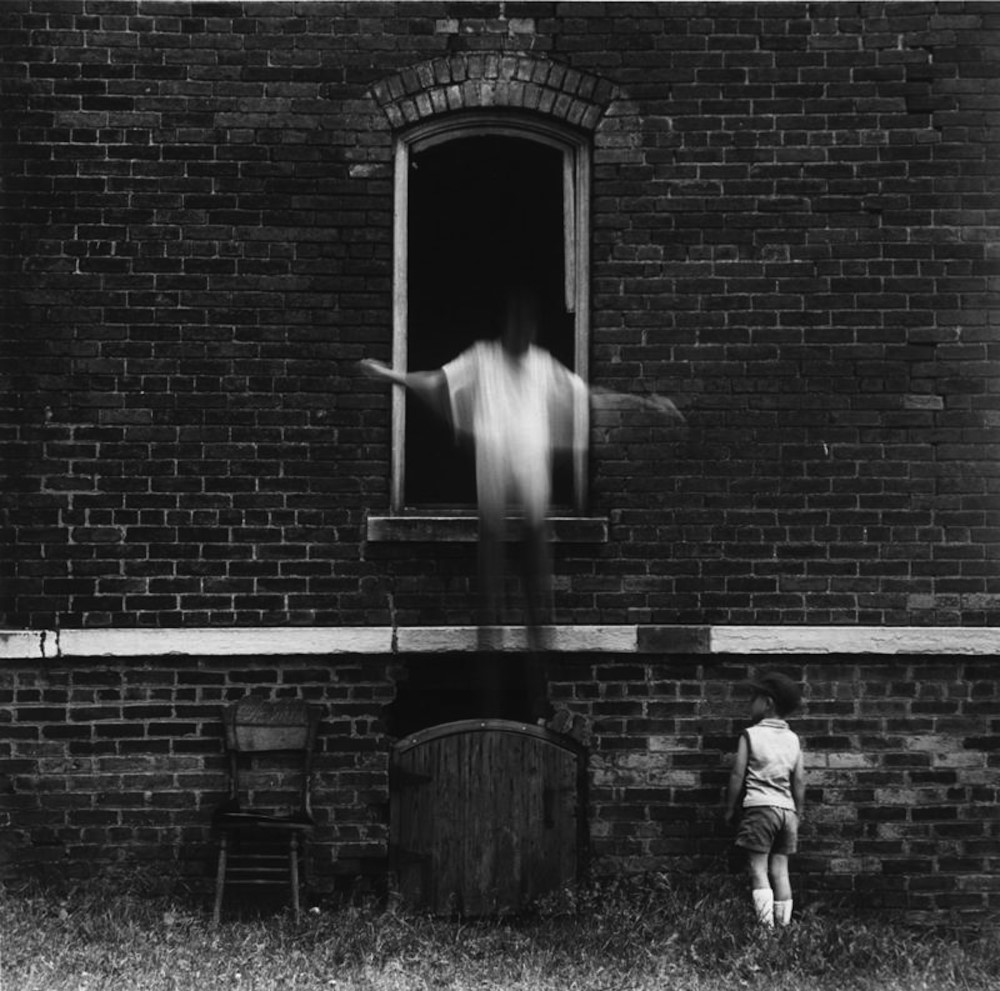

“Creative pictures must be felt in a similar way as one listens to music, emotionally, without expecting a story, information or facts.”

– Ralph Eugene Meatyard

Ralph Eugene Meatyard lived in Lexington, Kentucky, where he made his living as an optician while creating an impressive and enigmatic body of photographs. Meatyard’s creative circle included mystics and poets, such as Thomas Merton and Guy Davenport, as well as the photographers Cranston Ritchie and Van Deren Coke, who were mentors and fellow members of the Lexington Camera Club.

Meatyard’s work spanned many genres and experimented with new means of expression, from dreamlike portraits – often set in abandoned places—to multiple exposures, motion-blur, and other methods of photographic abstraction. He also collaborated with his friend Wendell Berry on the 1971 book The Unforeseen Wilderness, for which Meatyard contributed photographs of Kentucky’s Red River Gorge. Meatyard’s final series, The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, are cryptic double portraits of friends and family members wearing masks and enacting symbolic dramas.

Via: Smithsonian, Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.