On the 27th August 1883, the Krakatoa (Krakatau) volcano exploded and the sky changed colour.

Lying on the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra in the Indonesian province of Lampung, Krakatoa was hit by a series of four massive eruptions – the equivalent to 200 megatons of TNT; about 13,000 times the nuclear yield of the Little Boy bomb that devastated Hiroshima, Japan, during World War II.

The explosion was heard 3,600 km (2,200 miles) away in Alice Springs, Australia, and on the island of Rodrigues near Mauritius, 4,780 km (2,970 mi) to the west. Over 36,000 people are known to have died in the explosion and resulting tsunamis.

The pressure wave from the third and most violent explosion was recorded on barographs around the world. (A barograph is a barometer that records the barometric pressure over time in graphical form.) Several barographs recorded the wave seven times over the course of five days: four times with the wave travelling away from the volcano to its antipodal point, and three times travelling back to the volcano. The wave went round the globe three and a half times. Ash rose to a height of 80 km (260,000 ft).

The sky was much altered. The explosions formed memorable sunsets and afterglows across the planet.

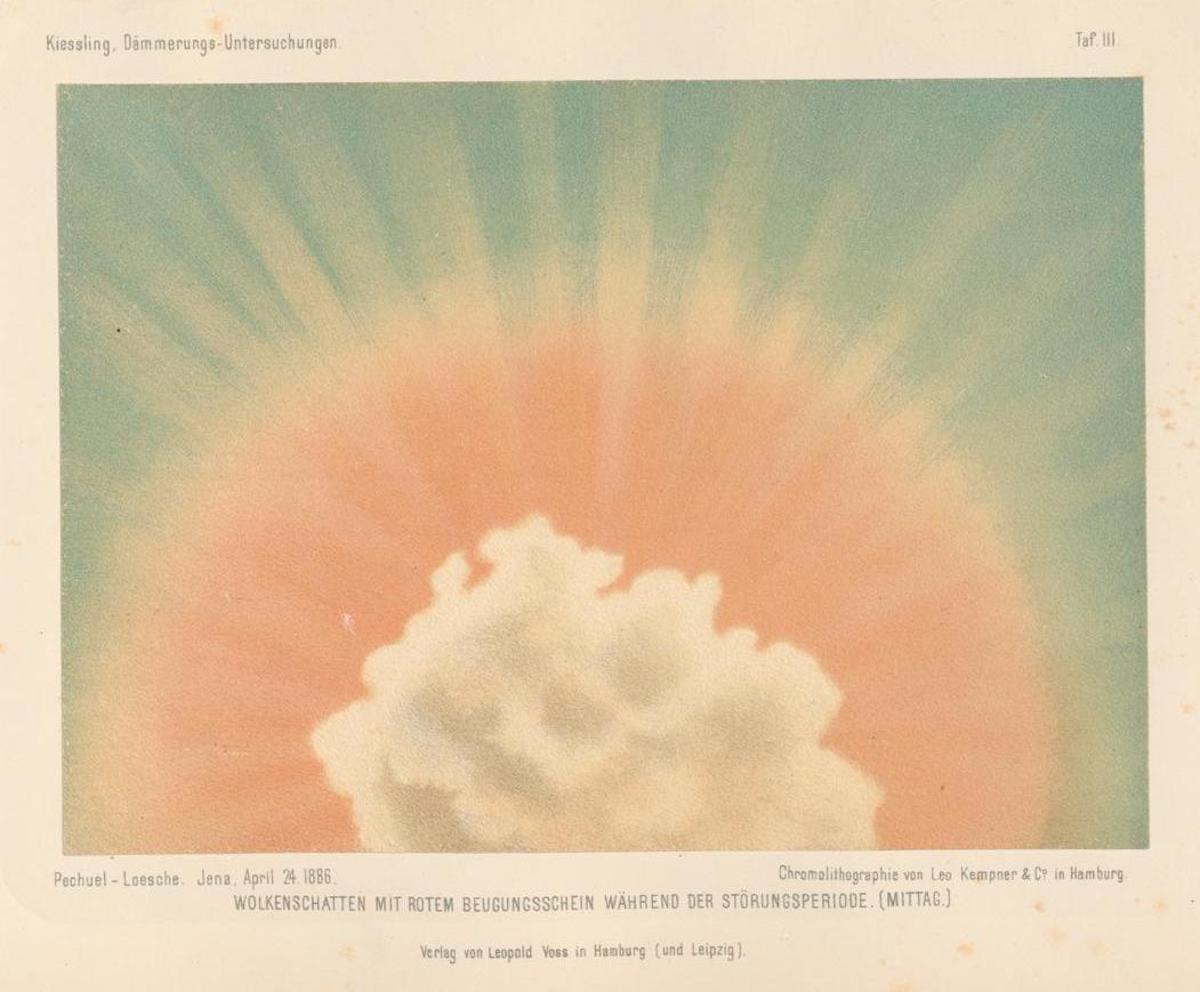

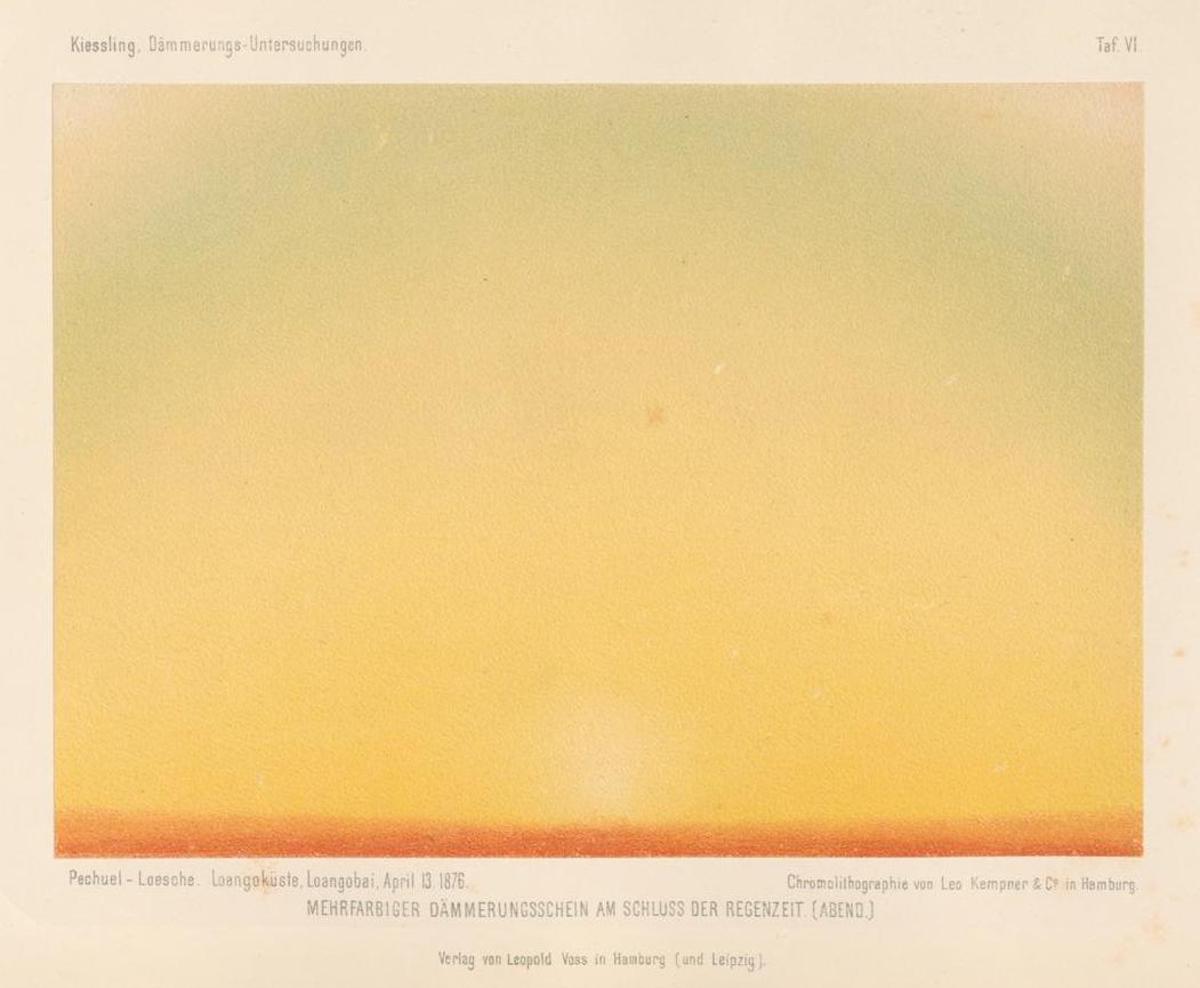

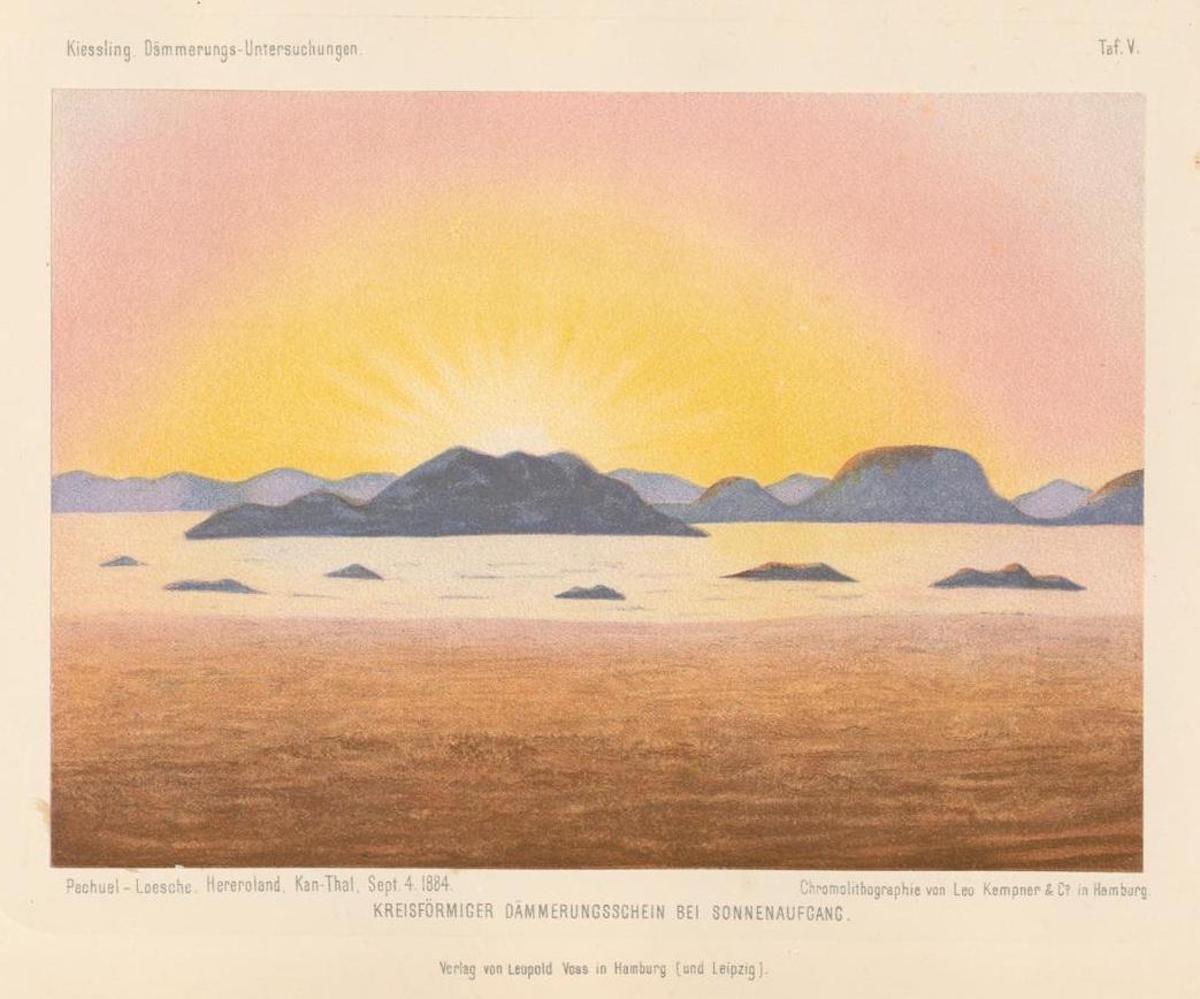

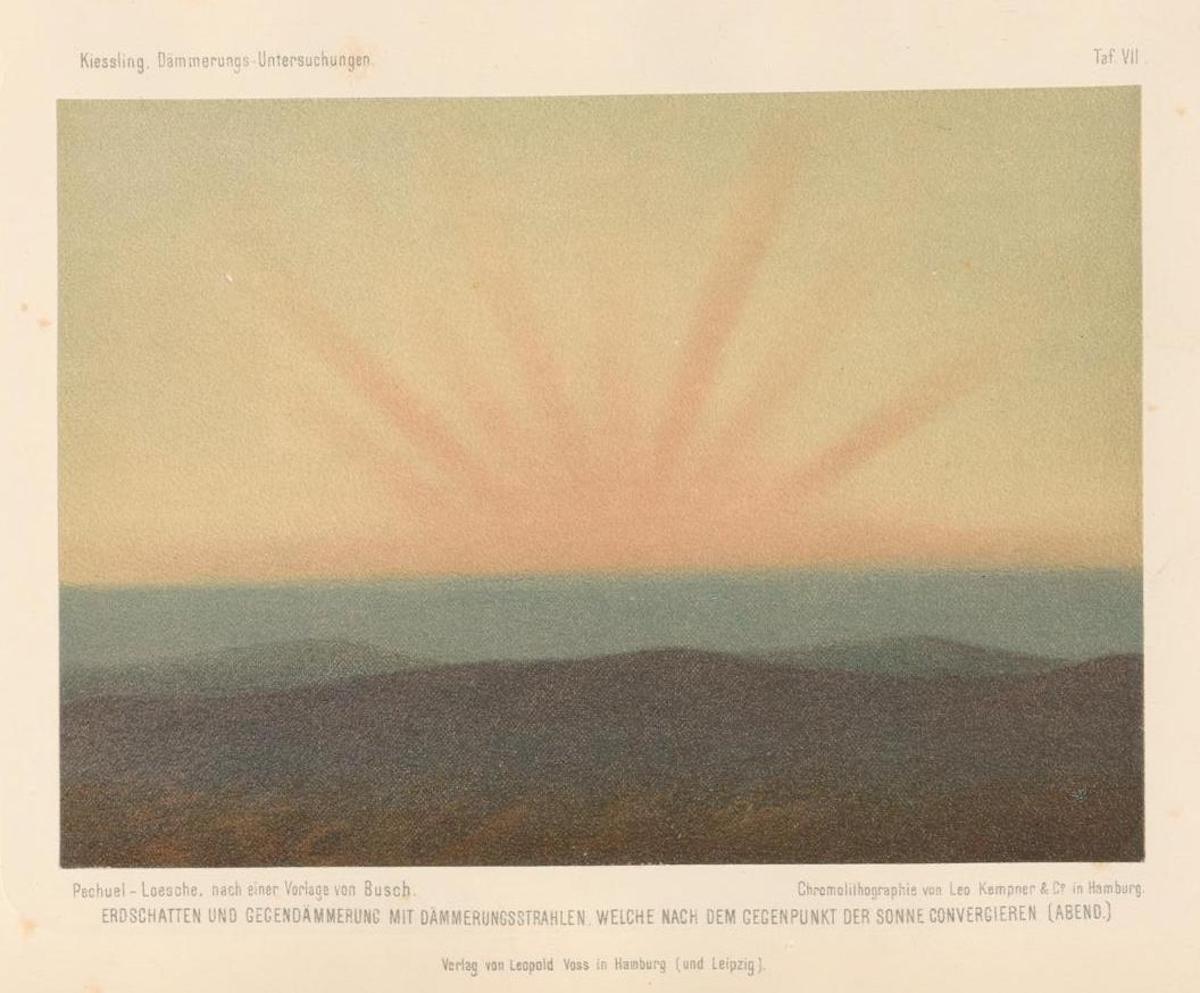

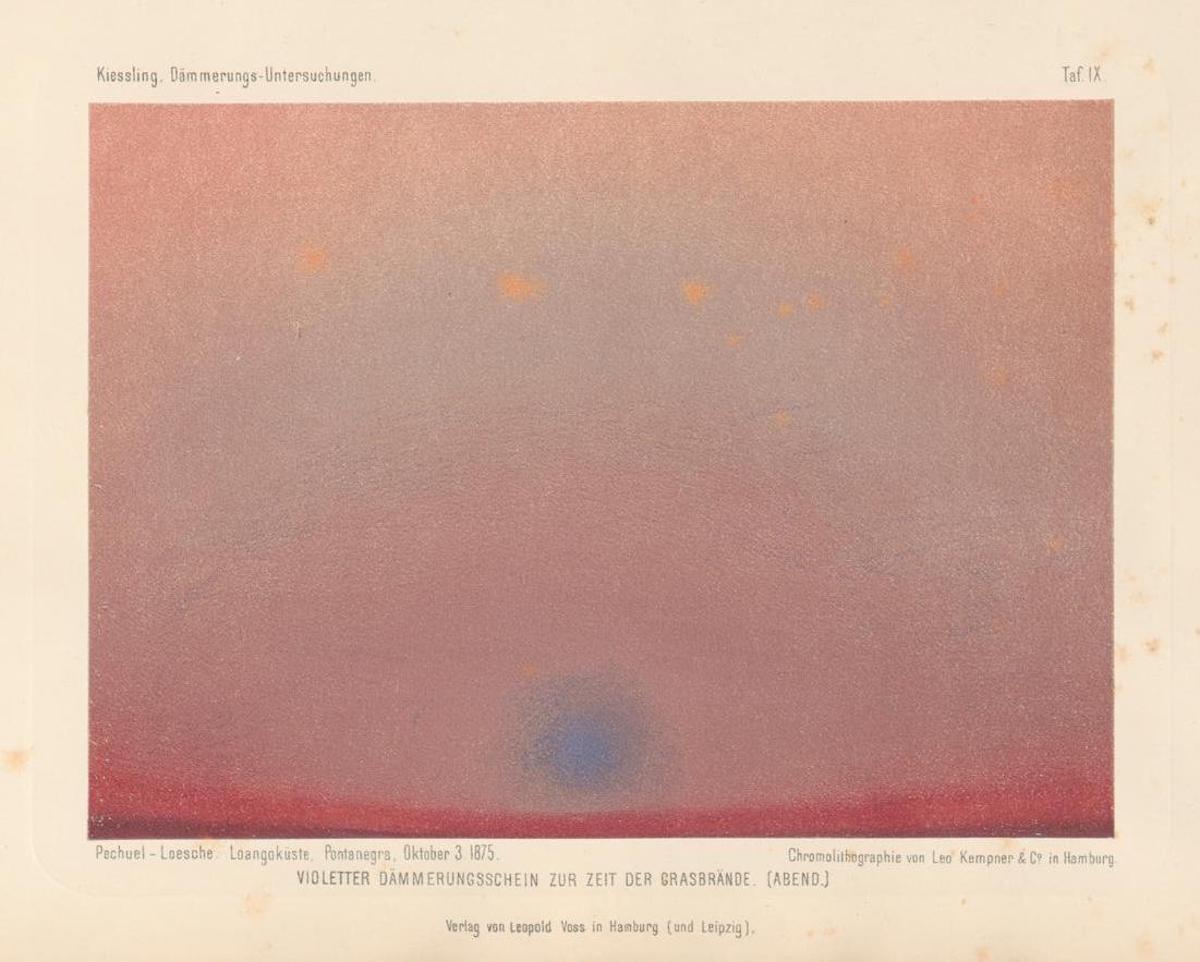

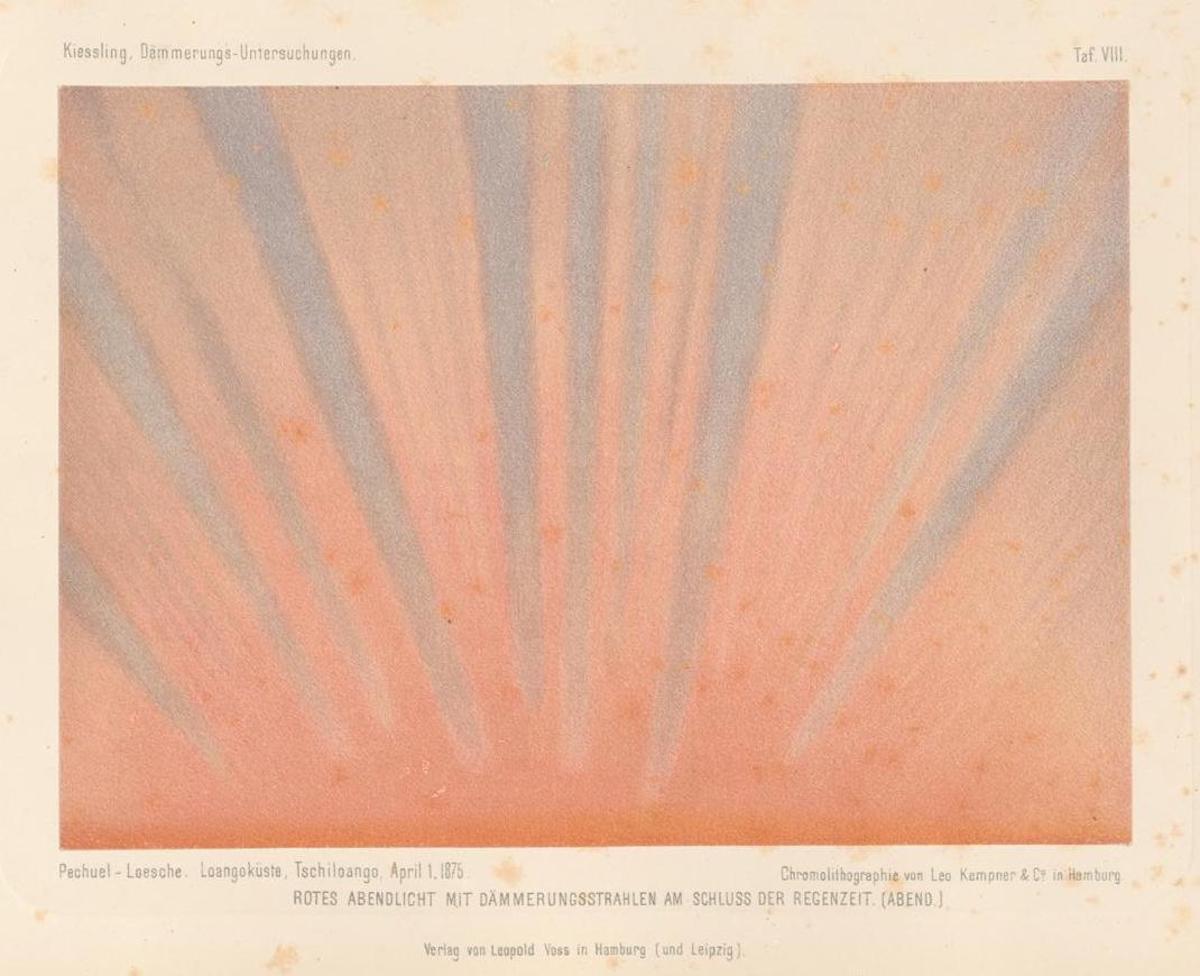

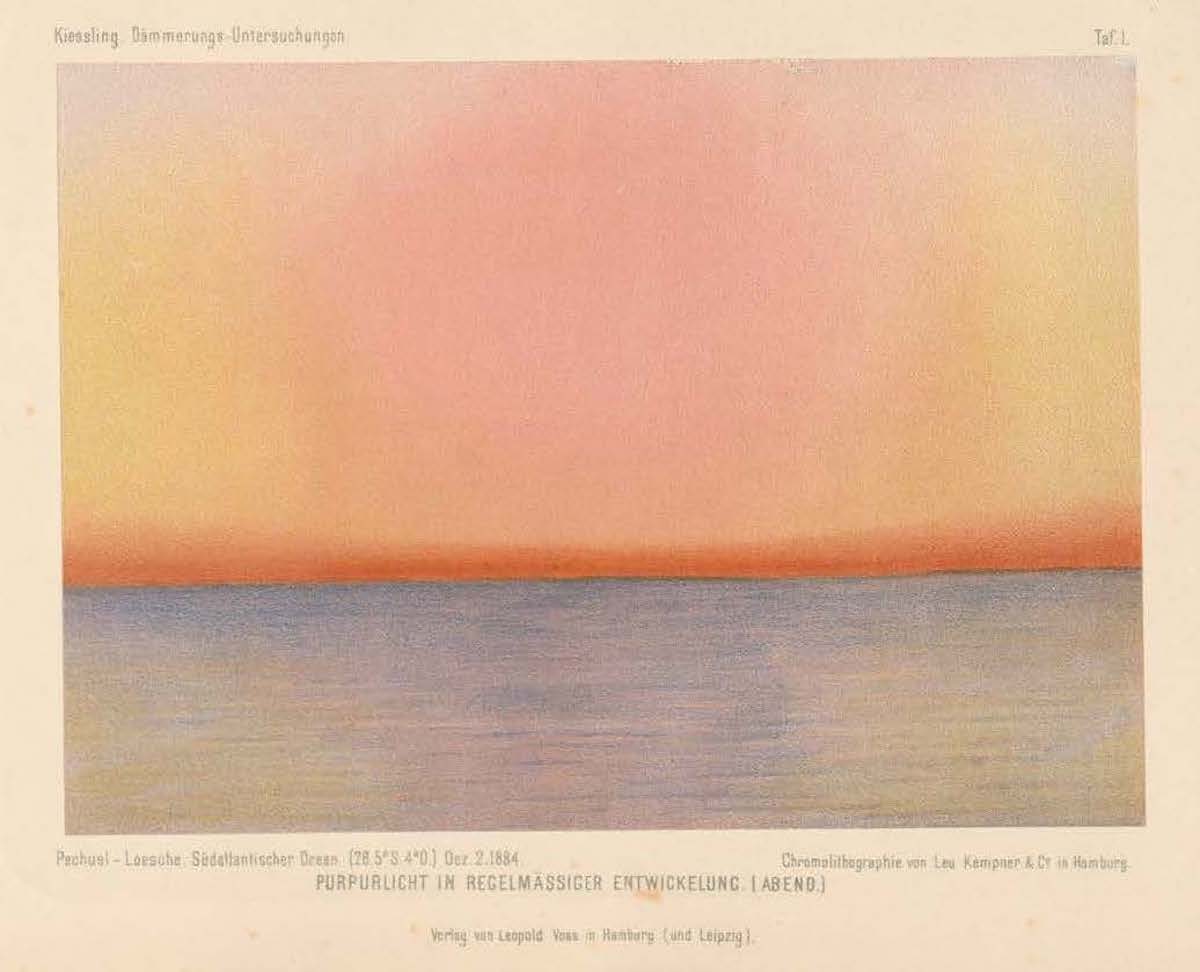

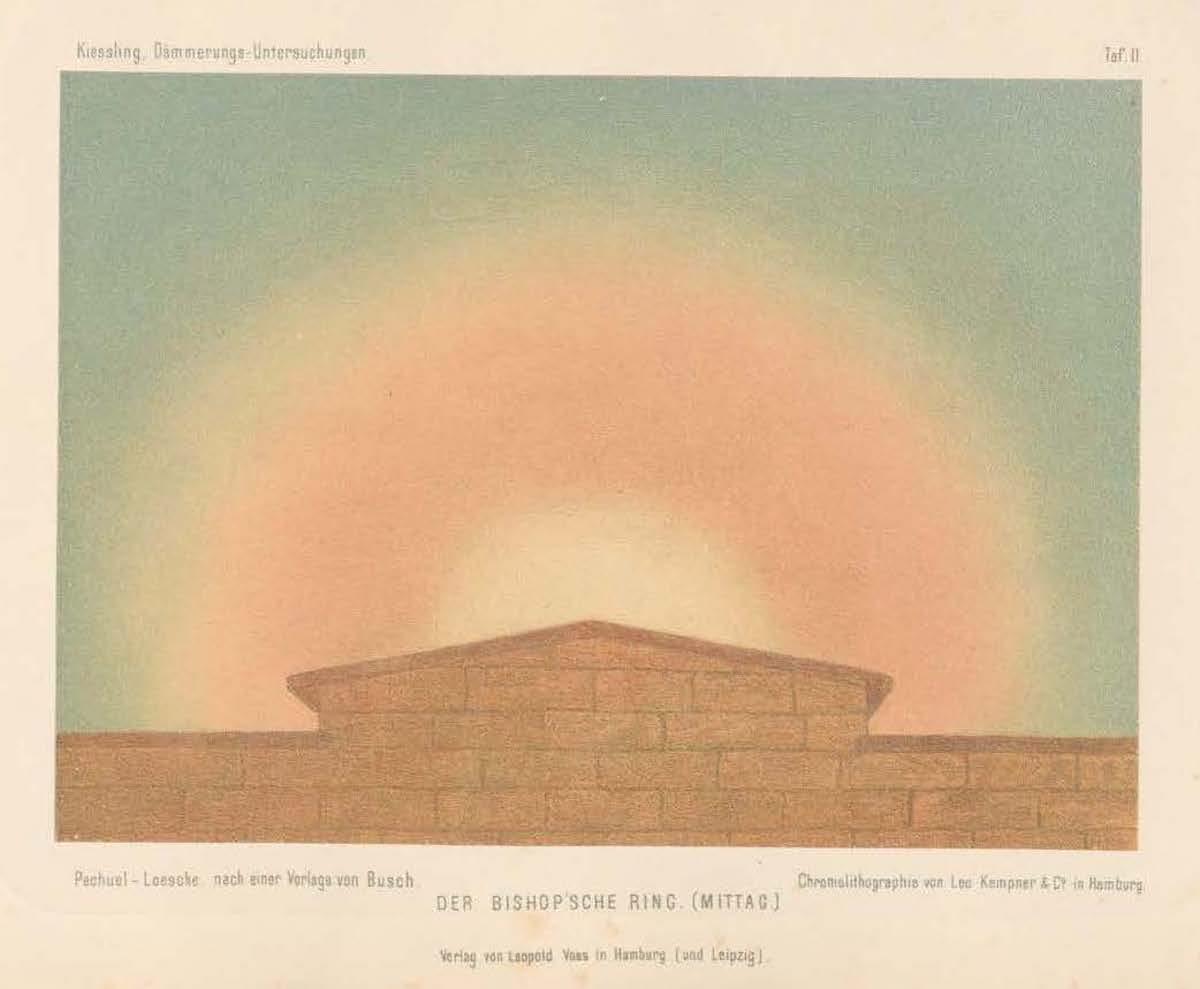

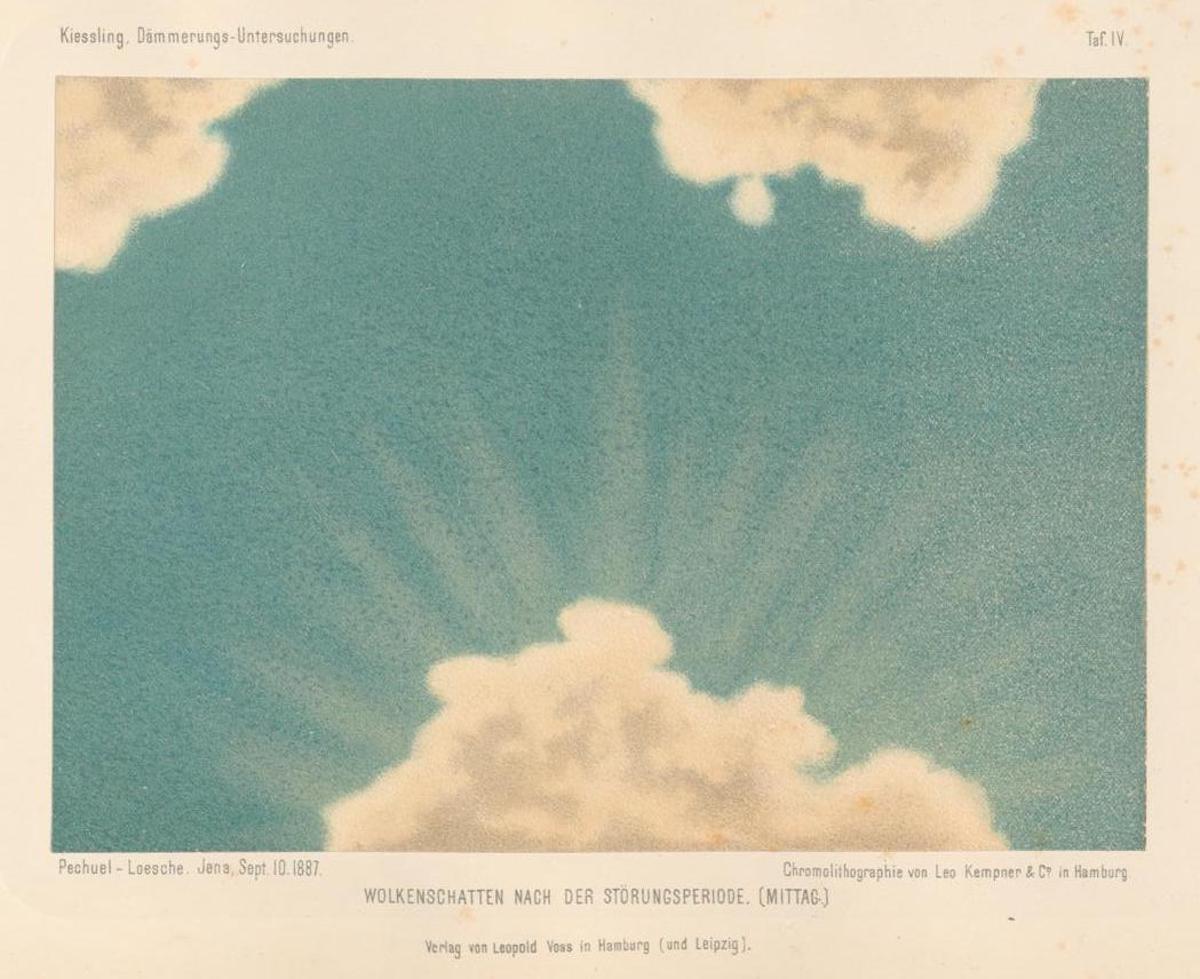

These visions were recorded in the German language book Untersuchungen über Dämmerungserscheinungen: zur Erklärung der nach dem Krakatau-Ausbruch beobachteten atmosphärisch-optischen Störung (Investigations into twilight phenomena: to explain the atmospheric-optical disturbance observed after the Krakatoa eruption) by German scientist J. Kiessling with nine colour plates based on watercolours by German artist and naturalist Prof. Dr. Pechuël-Loesche.

Presented as chromolithographs, Dr Loesche’s vivid pictures are all featured here (via).

The Volcanic Afterglow

Dr Tony Phillips explains:

Fine volcanic aerosols in the stratosphere scatter blue light which, when mixed with ordinary sunset red, produces a violet hue. The purple color is often preceded by a yellow arch hugging the horizon. As the sun sets, violet beams emerge from the yellow, overlapping to fill the western sky with a soft purple glow. High-quality pictures of the phenomenon often show horizontal bands cross-crossing the yellow arch. These bands are the volcanic gas.

That afterglow is caused by a stratospheric aerosol veil, a blanket of tiny volcanic particles suspended in the upper atmosphere.

Robin Andrews adds:

If you’ve got plenty of volcanic aerosols still up in the stratosphere, particularly on the horizon, then you’re just giving that poor blue light more particles to scatter off. That takes a little more blue light “away”, which reddens the sunsets even more. This seems to lengthen the sunsets, which creates that aforementioned afterglow.

In the UK, British poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (28 July 1844 – 8 June 1889) wrote of his observations in a letter published in Nature magazine:

Above the green in turn appeared a red glow, broader and burlier in make; it was softly brindled, and in the ribs or bars the colour was rosier, in the channels where the blue of the sky shone through it was a mallow colour. Above this was a vague lilac. The red was first noticed 45º above the horizon, and spokes or beams could be seen in it, compared by one beholder to a man’s open hand.

By 4.45 the red had driven out the green, and, fusing with the remains of the orange, reached the horizon. By that time the east, which had a rose tinge, became of a duller red, compared to sand; according to my observation, the ground of the sky in the east was green or else tawny, and the crimson only in the clouds. A great sheet of heavy dark cloud, with a reefed or puckered make, drew off the west in the course of the pageant: the edge of this and the smaller pellets of cloud that filed across the bright field of the sundown caught a livid green.

At 5 the red in the west was fainter, at 5.20 it became notably rosier and livelier; but it was never of a pure rose. A faint dusky blush was left as late as 5.30, or later. While these changes were going on in the sky, the landscape of Ribblesdale glowed with a frowning brown.

– G. M. Hopkins, The Remarkable Sunsets, Nature 29 (3 January 1884) (via)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.