In 1898, Carl Chun, a German marine biologist, set off on the steamboat Valdivia to explore the deep ocean on a yearlong voyage along the West Coast of South Africa, the Gulf of Guinea, the Antarctic Sea, and part of the Indian Ocean. He and his colleagues collected, writes the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), “as many biological samples as possible” and the “results of the expedition lead to 24 volumes” published over the course of forty years as Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition auf dem Dampfer “Valdivia” 1898-1899, or Scientific Results of the German Deep-Sea Expedition on the Steamer “Valdivia” 1898-1899.

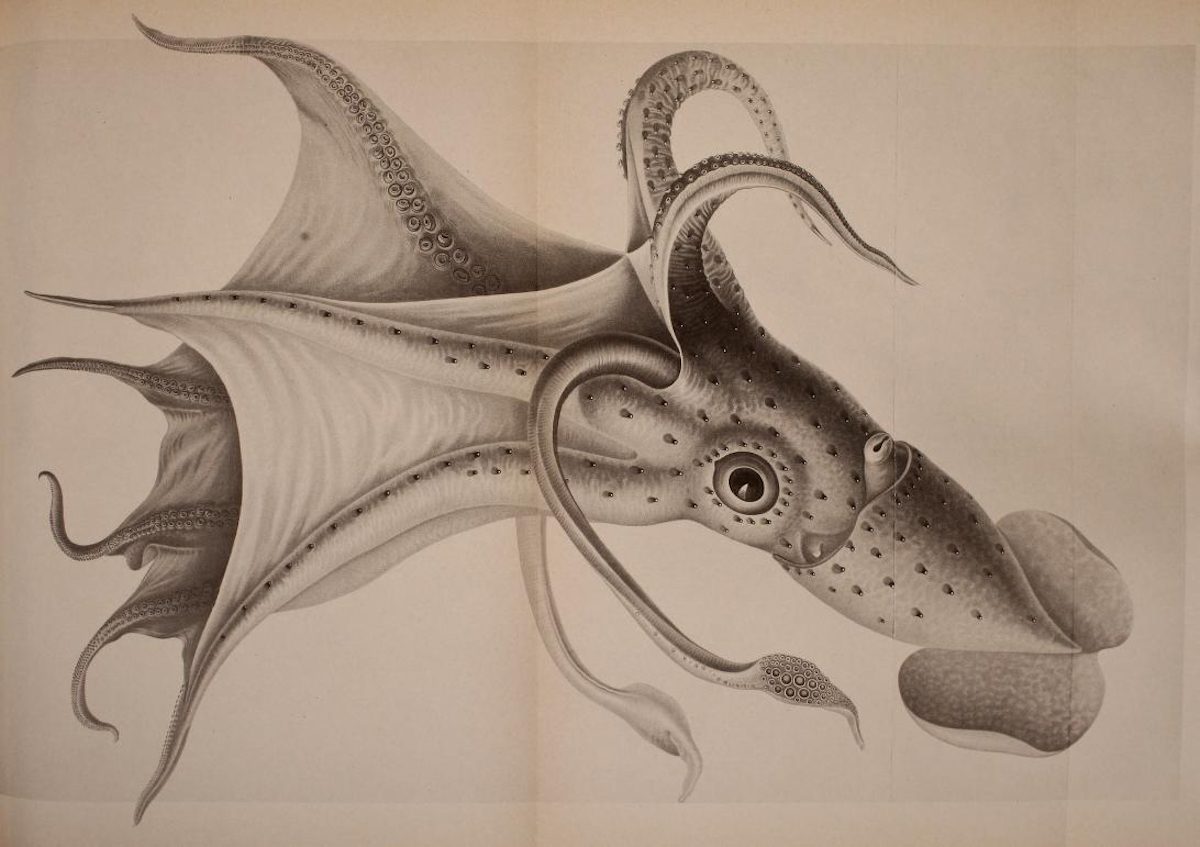

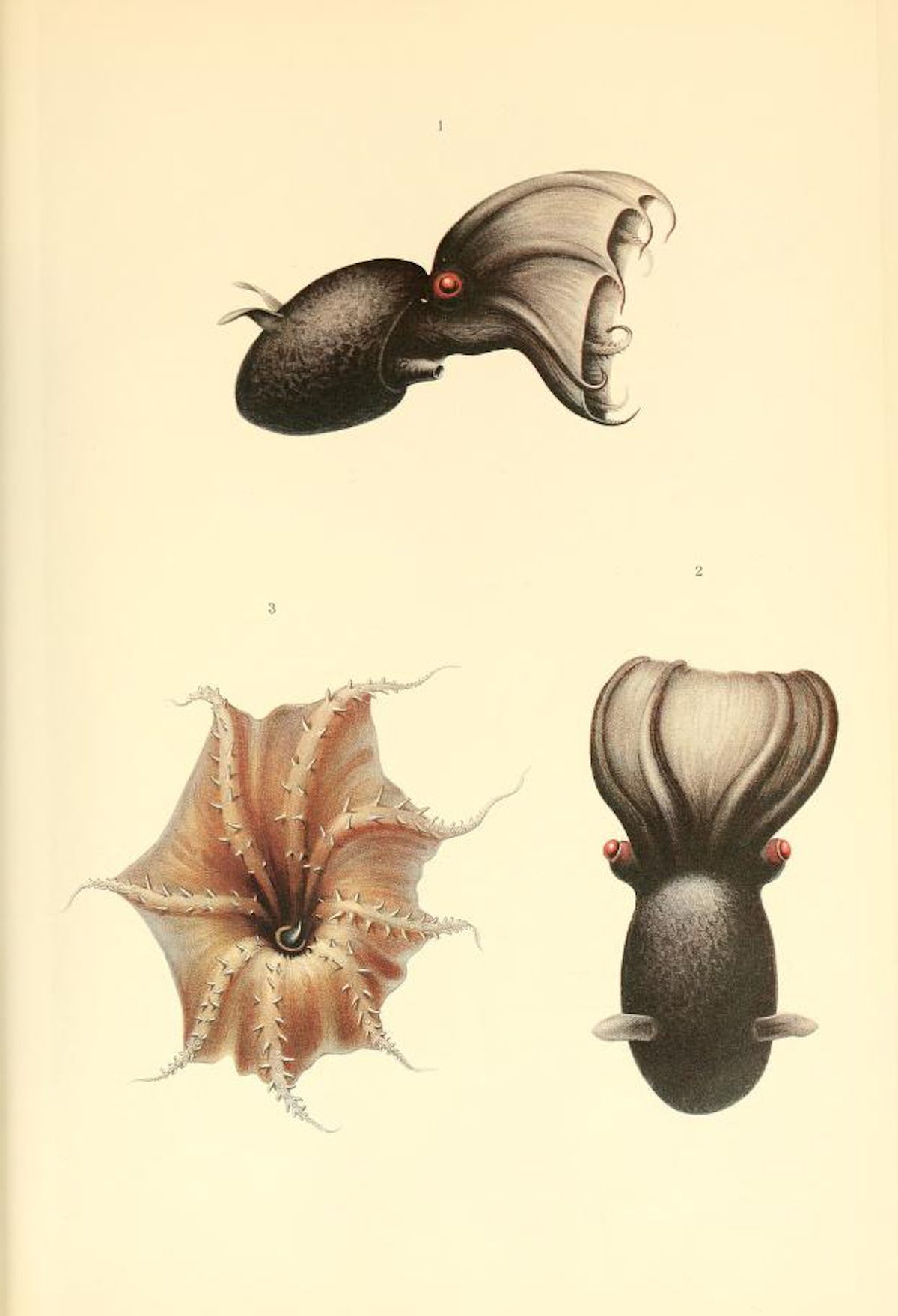

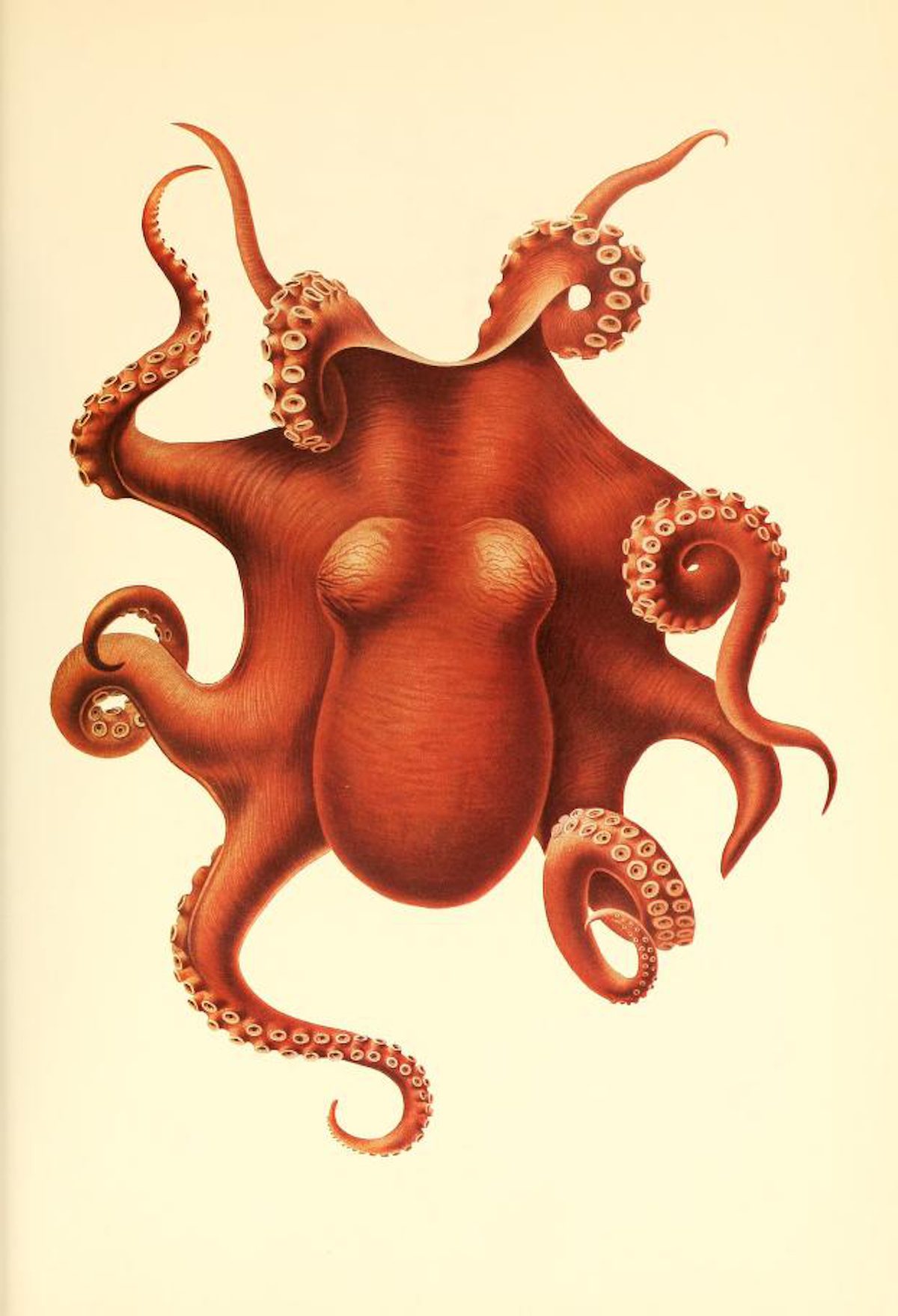

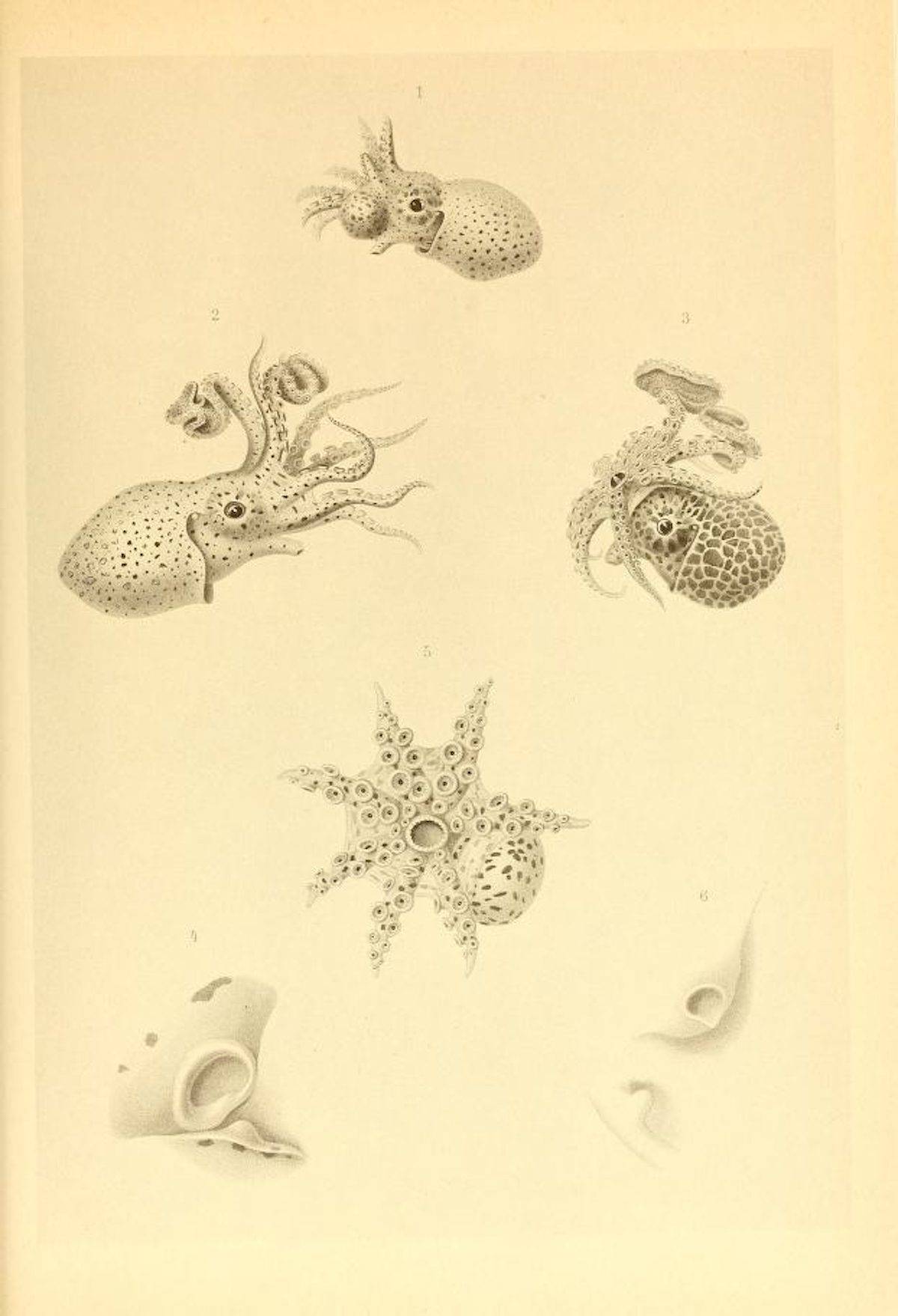

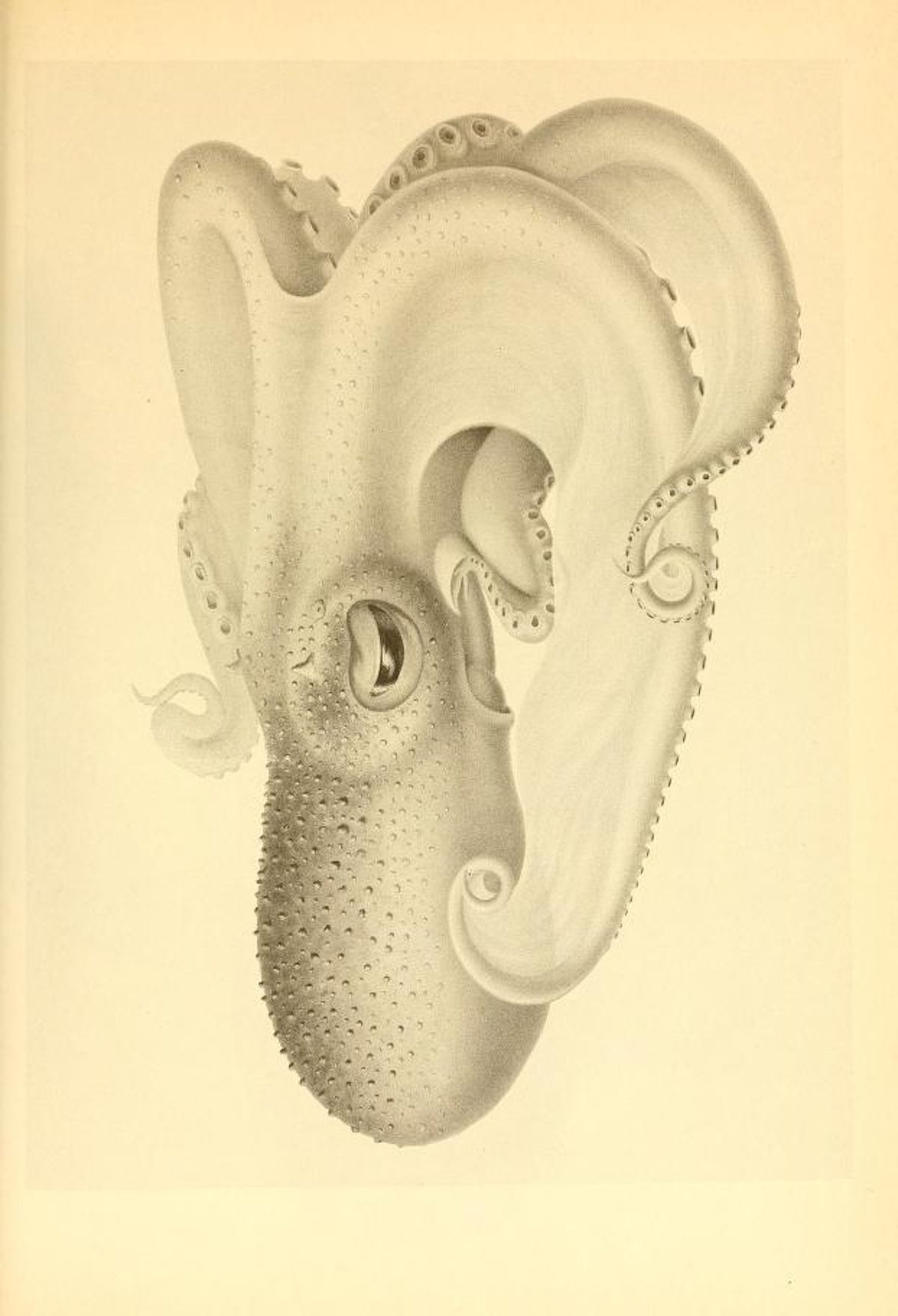

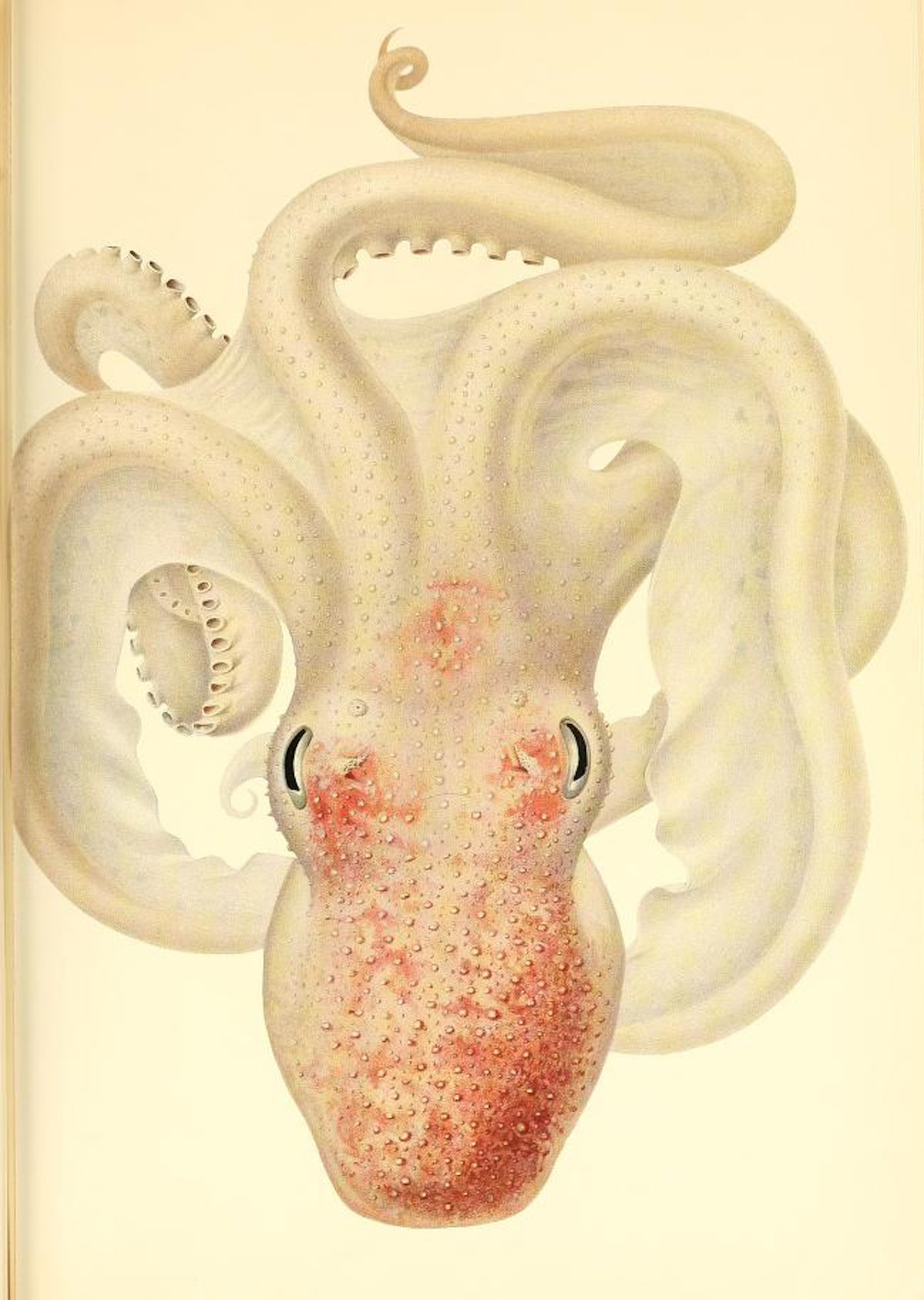

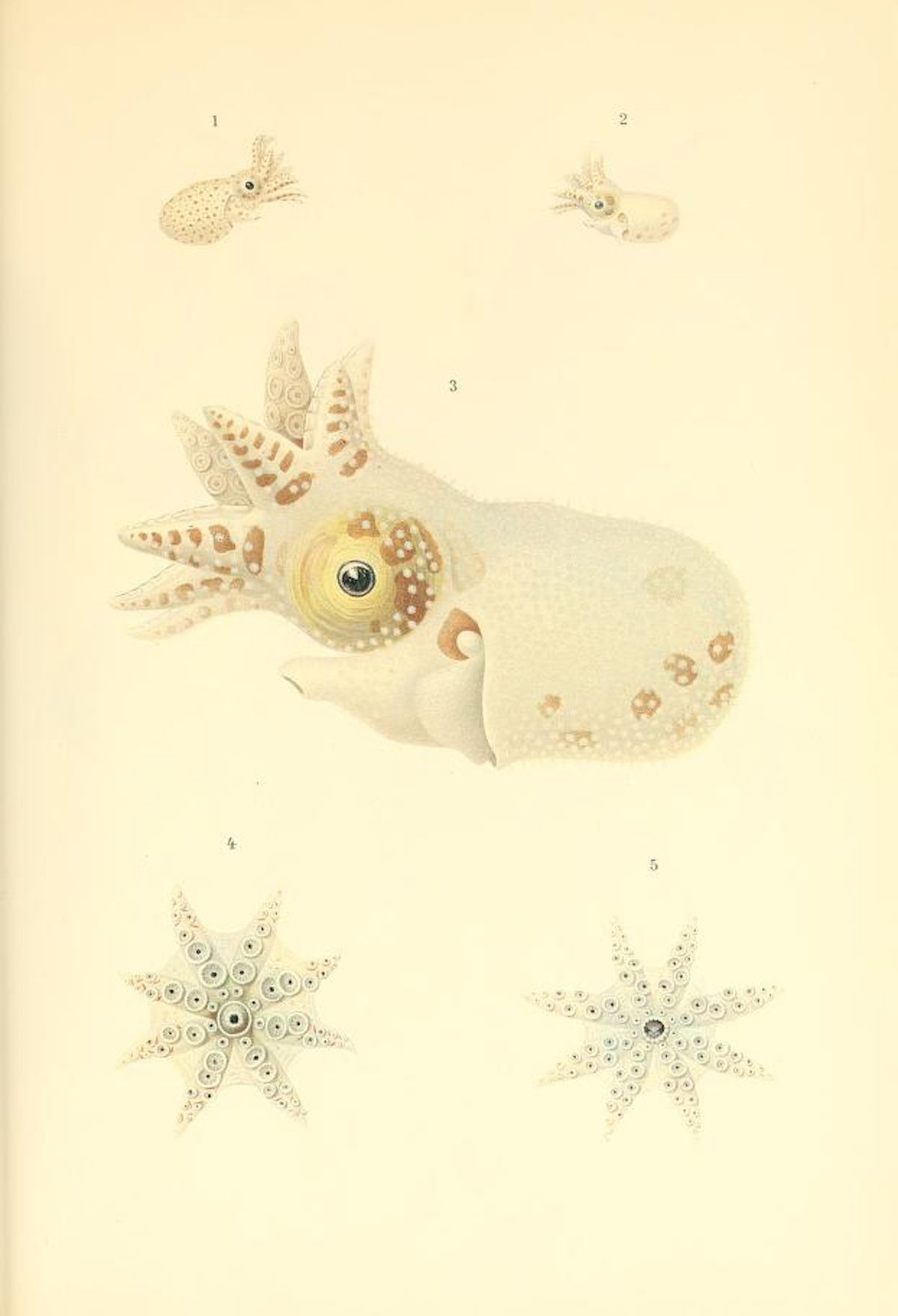

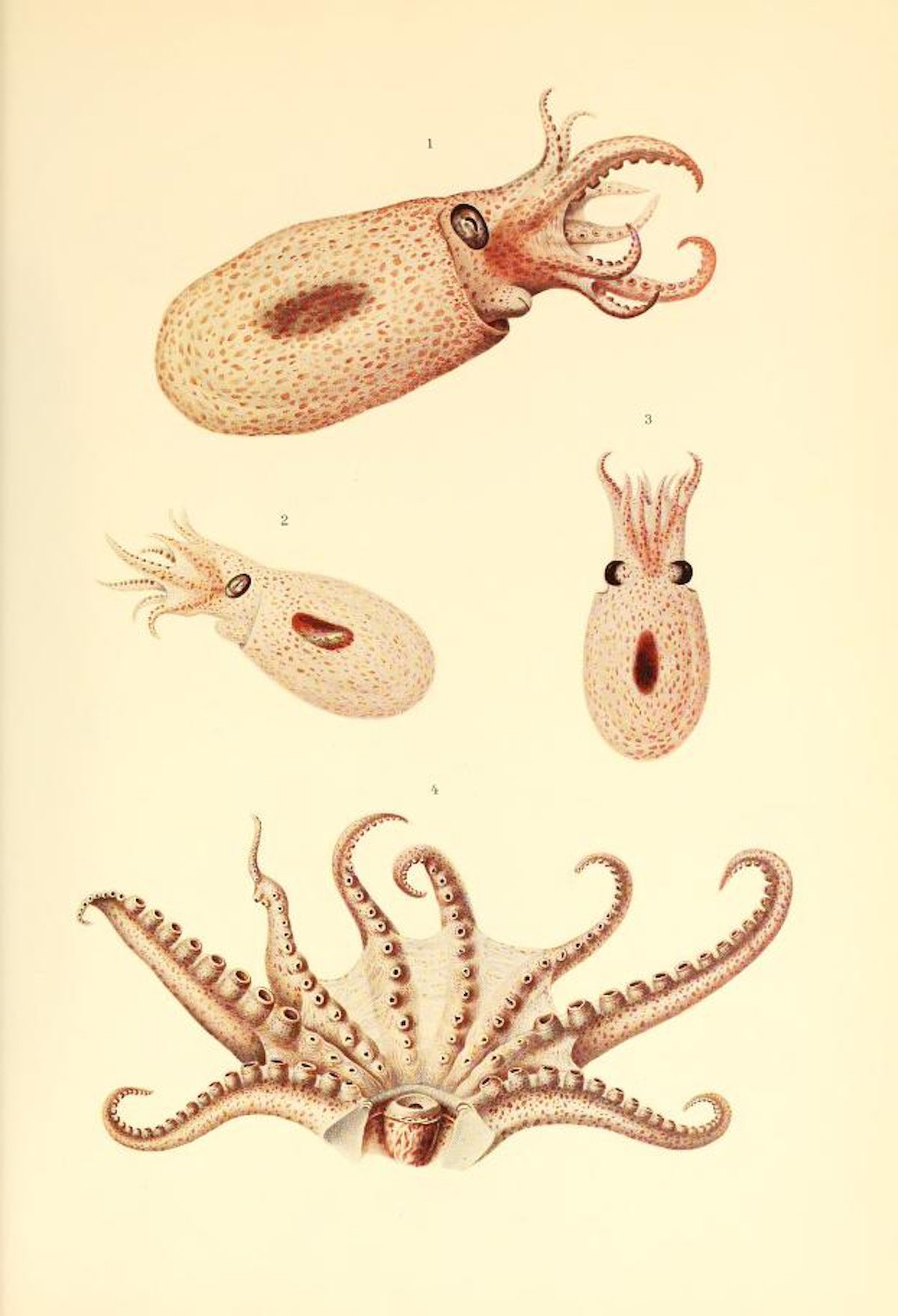

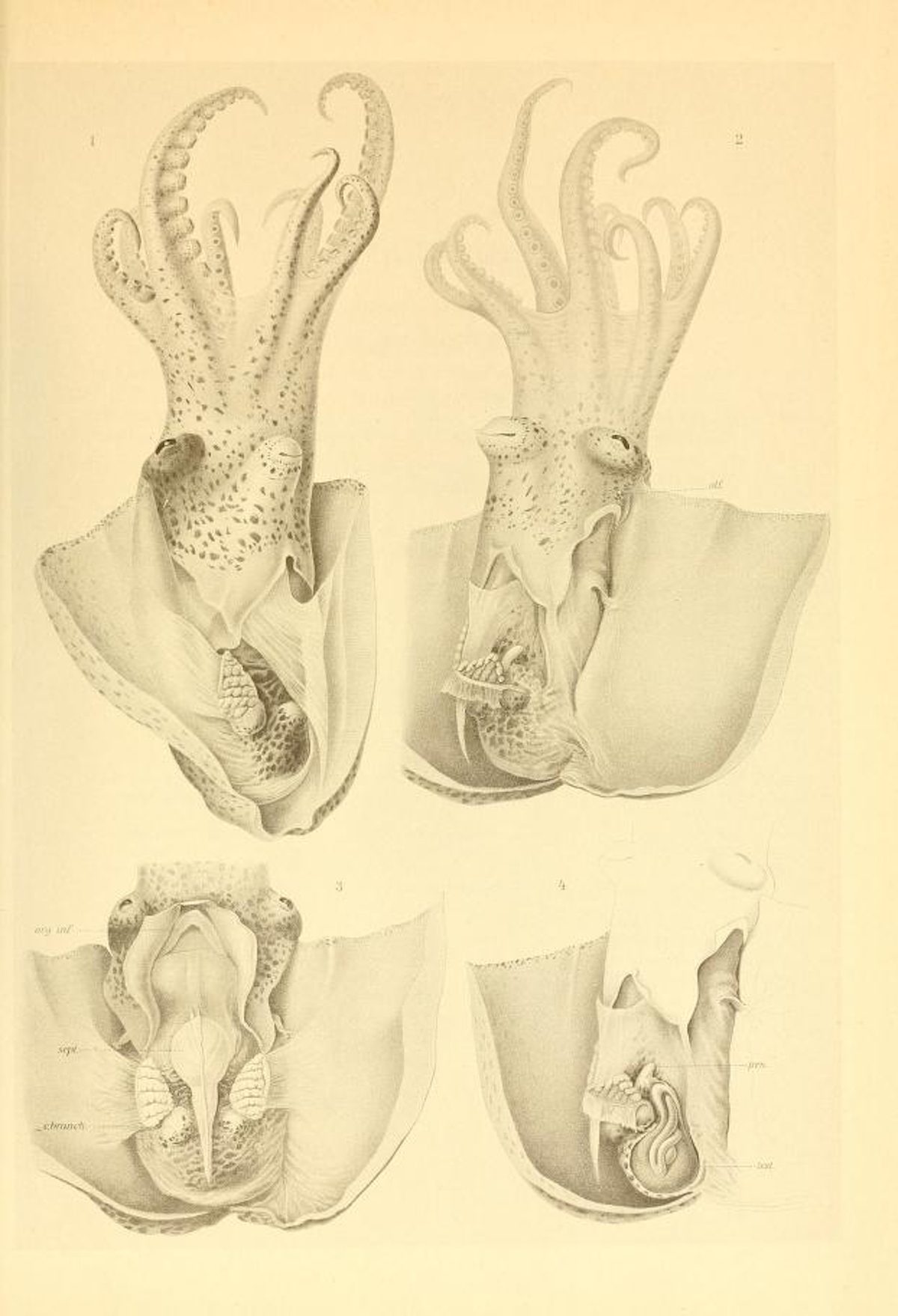

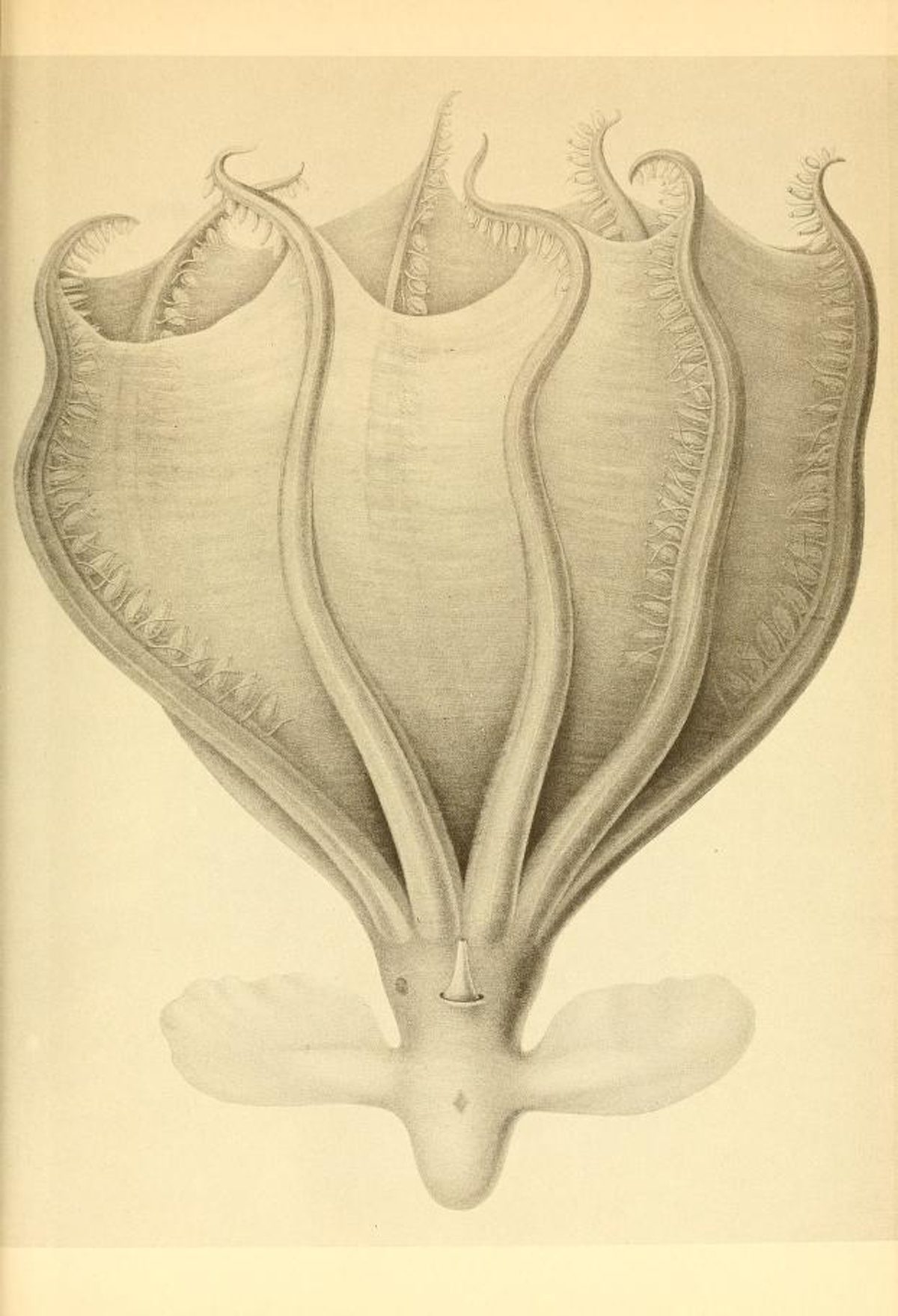

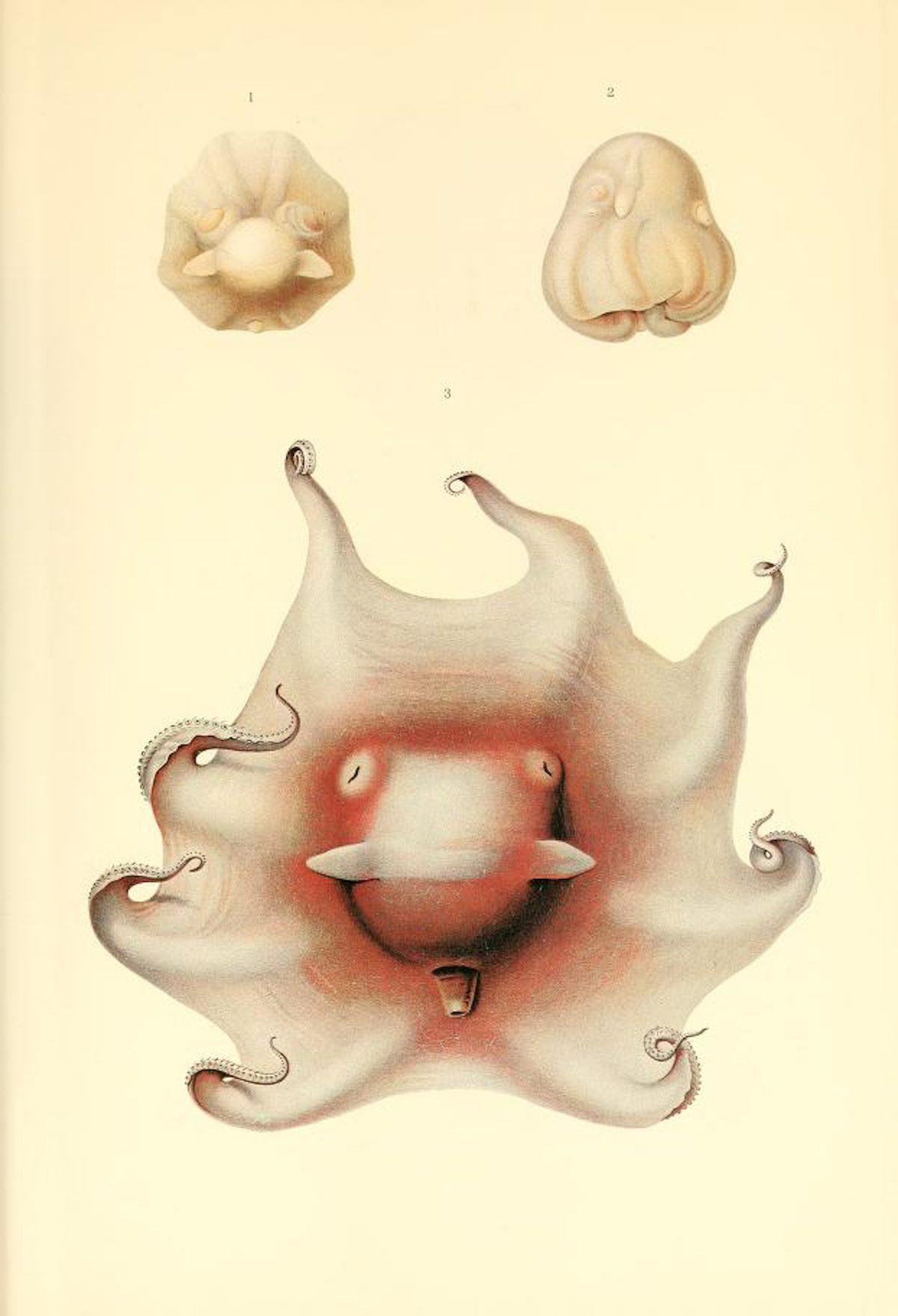

While on the expedition, Chun discovered a species so terrifying, he called it Vampyrotheuthis infernalis, or “vampire squid from hell,” just one of the many creatures he found, then dissected, labeled, and named. “Chun spent the remainder of his life bringing the world’s awed attention to the unfathomed wonderland he had discovered,” writes Brain Picking’s Maria Popova. He wrote or edited several of the expedition’s “rigorously detailed volumes, some featuring arresting, almost erotic illustrations by the artist Friedrich Wilhelm Winter.” Rarely are these illustrations finer than in volume eighteen of the series, Chun’s own contribution, “1910 treasure Cephalopod Atlas,” or Die Cephalopoden, a taxonomy of the octopuses and squid he encountered, with a set of gorgeous full-color prints (and a smattering of photographs).

The dee-sea specimens Chun found—and that expedition artist Winter captured with stunning vibrancy—made a significant impact on oceanography, a science only lately deemed possible after the four-year voyage of the H.M.S. Challenger, which set off in 1872 to circumnavigate the globe and collected “4700+ previously unobserved and unnamed species,” the BHL explains. For all its success, however, the Challenger did not find evidence to refute “the widely accepted mid-19th century Abyssal Theory, which held that life could not exist at more than 300 fathoms under the sea.”

Chun, convinced that the deeper regions teemed with life, secured funding from Kaiser Wilhelm II himself and traveled to 268 different stations, covering a little less than half the distance of the Challenger. He and his colleagues returned “with so many new specimens that they would continually publish their findings over the span of 4 decades.” Chun supervised the publication until 1914, after which zoologist August Brauer, one of the thirteen scientists aboard the Valdivia, took over.

See Winter’s incredible illustrations for Brauer’s own contribution, volume fifteen, Deep Sea Fish (Die Tiefsee-Fische), at the BHL’s Flickr, read an English translation of Chun’s Cephalopod Atlas here, and see all of Winter’s finely-rendered squid and octopuses at the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.