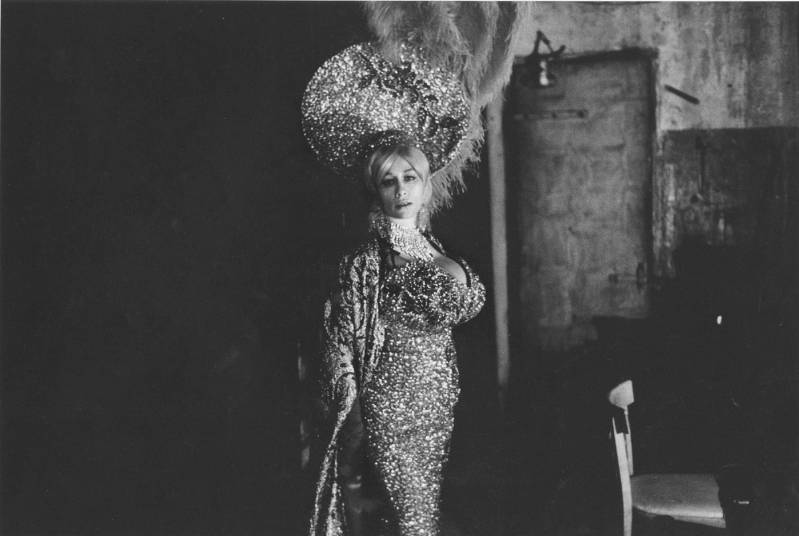

“You can tell showgirls from strippers, sometimes, by their stage names: Jeri, Deirdre, Melanie, Coty Lee; on the other hand, Devil’s Delight, Satan’s Angel, Blaze Starr, Tempest Storm, Honeysuckle Devine. The effects they are calculated for are miles apart.”

– Roswell Angier in A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone

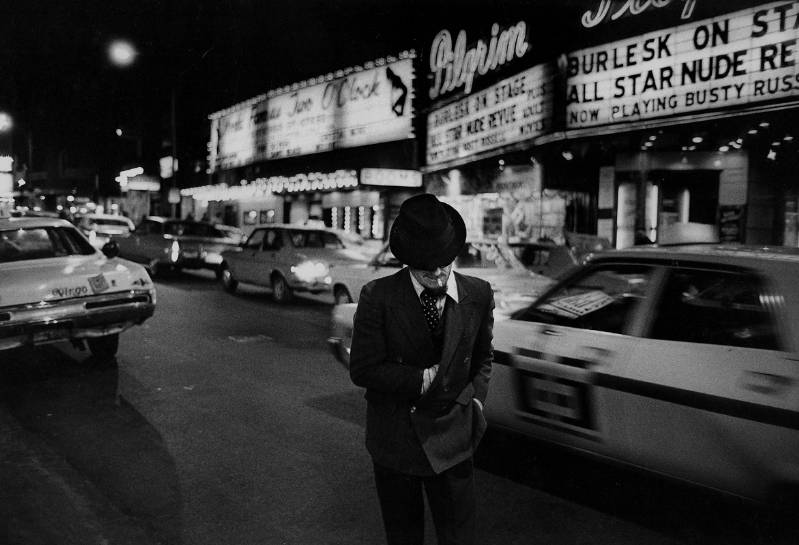

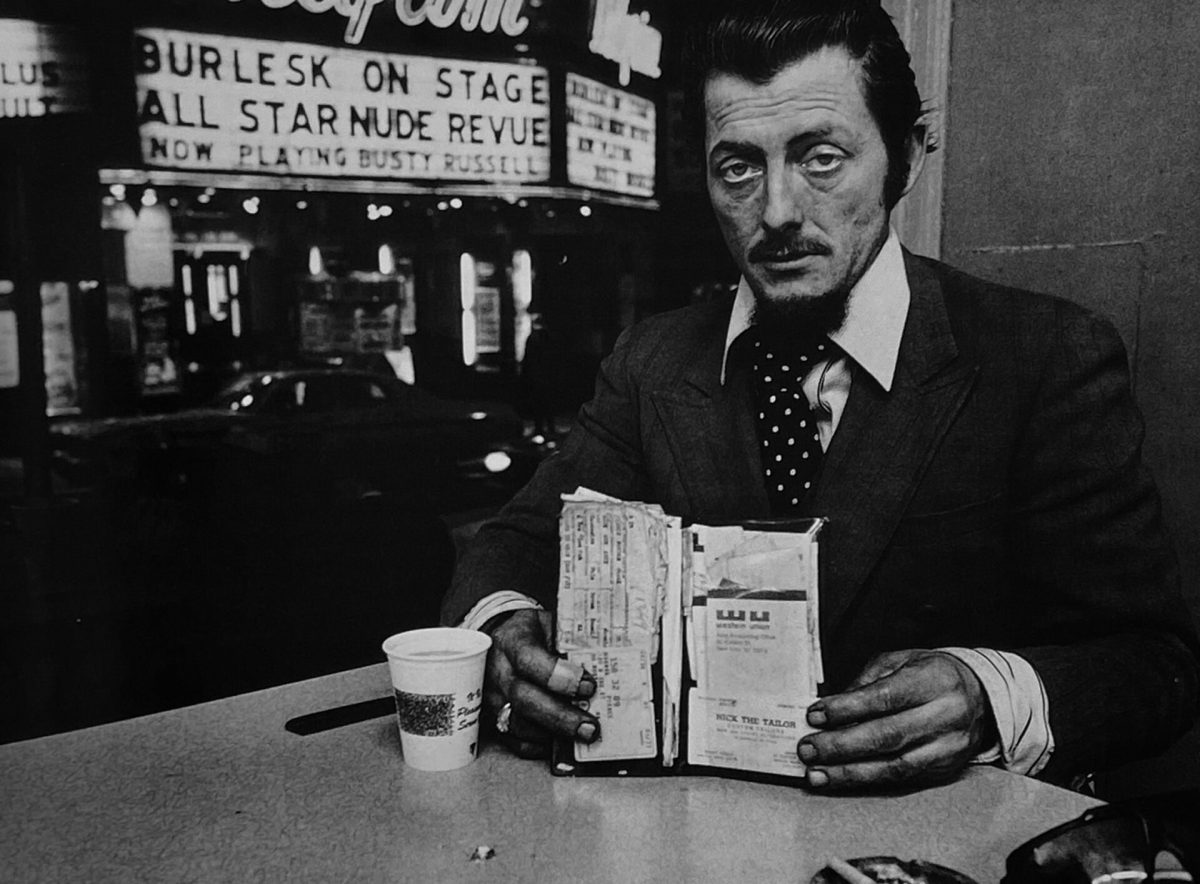

In the 1950s Boston was a major Navy port. Sailors on shore wandered the area around Washington Street looking for drink and guiltless sex. This was the city’s ‘Combat Zone’, so named after the Shore Patrolmen, who kept the peace with extreme prejudice. From 1973-75, photographer Roswell Angier (2 December 1940 – 23 May 2023) photographed the area. The sailors and patrolmen were gone, and the place was one of bars and strip clubs.

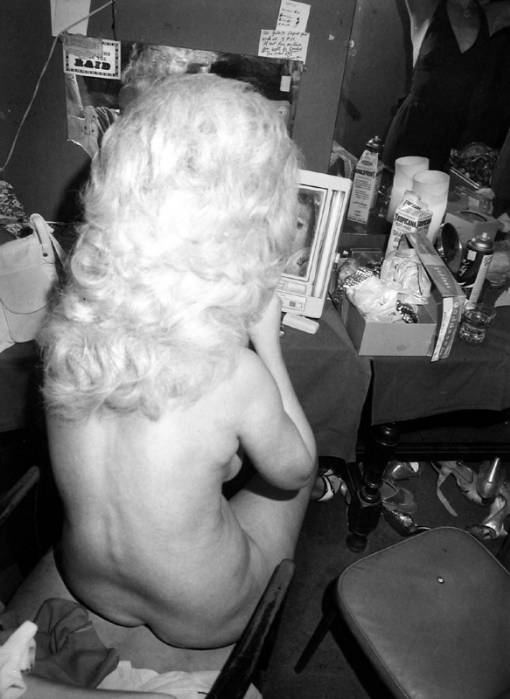

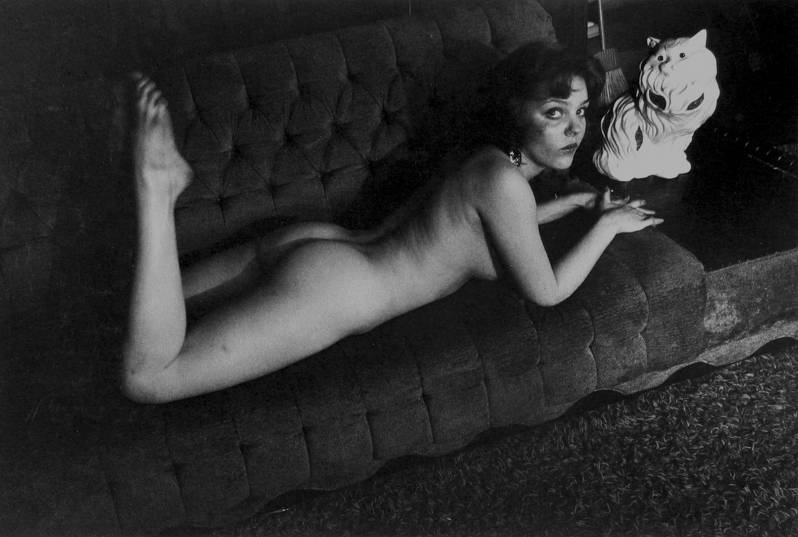

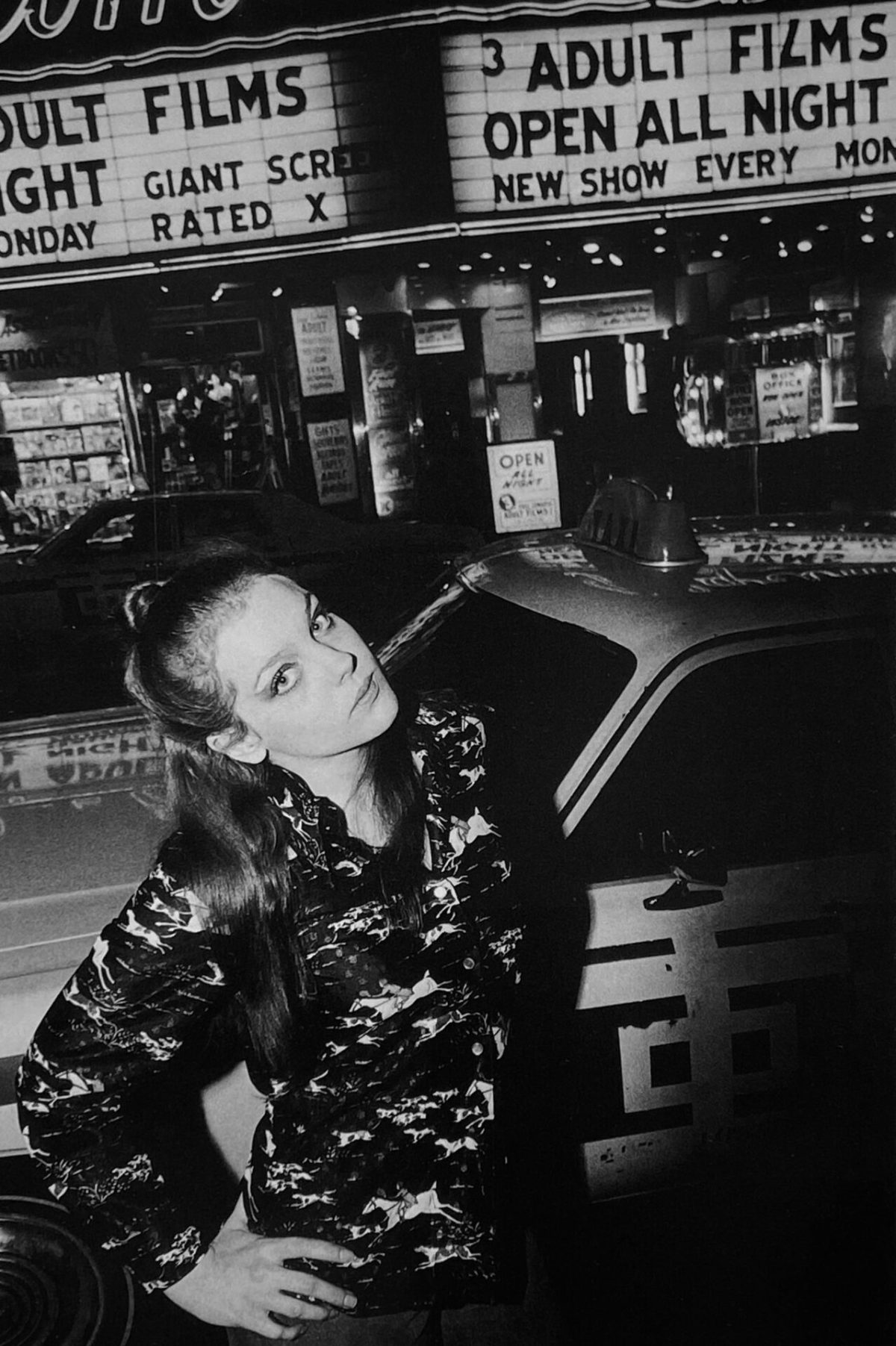

Much like EJ Bellocq had done decades earlier in New Orleans’ Storyville quarter, Angier became acquainted with many of the prostitutes, strippers and showgirls. Angier shows us the human side of the business of human flesh – “…there is a lot which they never reveal on stage, or in their breezy conversations in the dark shadows of the clubs; qualities of grace, wit, resilience, and singleness of heart.” His eye was compassionate and the book A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone (1976) includes conversations he had with his subjects.

Chesty Morgan, “The Zsa Zsa Gabor of Burlesk”, Pilgrim Theater, 1973

“It seems like what has been done in the way of magazine articles and stuff like that”, one of the strippers at the Two O’Clock Club tells me, “has to do with the really raunchy girls. Or the really freaky looking girls. There’s this one girl, for instance, who’s even bigger than Chesty Morgan. She is, honestly. Her breasts are bigger than watermelons. She has to harness them up.” She tells me about Honeysuckle Divine, who does “pussy tricks” on stage, like playing harmonicas with her cunt. And she talks about the prevalence of silicone; about a girl who had injections in her breasts, thighs, legs and buttocks. She is quite matter-of-fact about it. “After a while,” she says, “you get to be able to tell who’s had silicone. The top of the boob doesn’t move at all. It’s like cement. There was one girl who had some shots in her nose and her cheeks. She had to sleep sitting up every night or it would slip into some other part of her body.”

– Roswell Angier in A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone

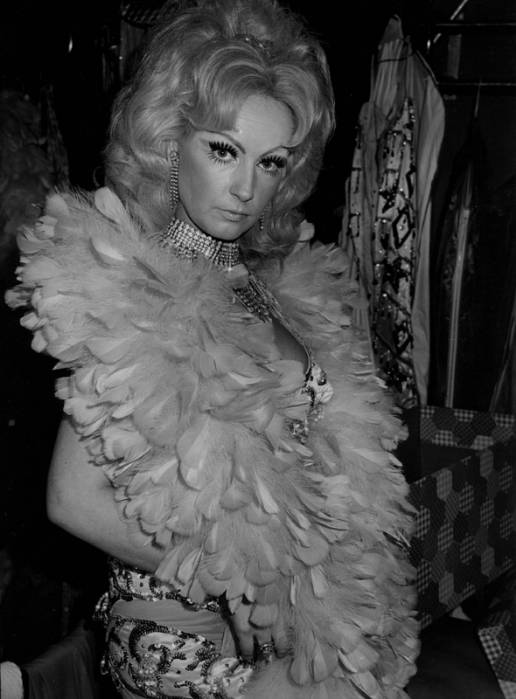

Coty Lee, 1976

“Zone people,” according to a bartender who has worked in the area for a long time, “are day-to-day survivals. I’m not talking about the guys who own the clubs and invest in business outside the area. They’re the only ones who are keyed for long-term survival. And they’re the only ones who don’t often make mistakes.

– Roswell Angier in A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone

At some of the other clubs, I learn about silicone and sex-changes: about Carla, a man with silicone breasts who ties his penis back between his legs and covers it with a wig of female pubic hair; and Andrea, whose whole body has been refashioned with surgery and silicone. Andrea would not consent to be photographed. She worries about being manipulated, about having her picture published in a girlie magazine. She warns me that she is a nice girl, that she has a husband with connections. “You just want to see my cunt,” she says. “But I don’t show my cunt to everybody, I don’t care what you think, I’m married, and I don’t do that stuff. So you better be careful. My husband’s out there, and he’s watching you.” Before she goes on stage, she crosses herself and bends over to touch the floor in front of her feet. Her body movements are abrupt and disconnected. Her hips, perhaps because of the tight gown, seem to collide with invisible objects.

– Roswell Angier in A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone

Showgirls do not come on as messengers of a forbidden orgasm. “Have you seen Faye Harlowe?” one of the people who works in the office at Two O’Clock asks. “She could be a real showgirl. I mean that girl dances. And she’s a lady. She never gets down on the floor. I don’t like girls who get down on the floor, because the minute they do that, they’re on eye-level with the customers, and they never should be. Customers should always have to look up at them, and remember that they’re ladies.” In trade jargon, it is a matter of “class”, a strict adherence to certain generally agreed-upon modes of behavior. To be classy is to be a survivor, and that is what this game is all about.

Cool and sometimes ladylike, a showgirl’s personal style is her armor, her defense against her own vulnerability. Ideally, she doesn’t make easy mistakes, like falling in love with a musician, going out a lot with customers, getting uses and abused by men in the more obvious ways. She is not perceptibly tough when she is out on the floor hustling drinks and chatting between shows. Nested away under the formulated girlish put-offs and double rows of eyelashes, predictably innocent dreams of another life take place. A car. A nice apartment. Good clothes, money in the bank. A businessman. Someone in a tailored suit. Someone with class.

– Roswell Angier in A Kind of Life: Conversations in the Combat Zone

“The difference between the guys that most of the girls get tied up with and pimps is that the guys don’t realize that they’re pimps. Or the girl doesn’t recognize herself as a hooker. But it’s the same game, the same basic set-up, no matter what they try and tell themselves. It may not be conscious, but it’s there. The guy plays, the girl works. What’s the difference? The only difference is the Cadillac, the flash roll, and the way the money’s comin’ in.

“In other words, at least to the best of my knowledge, a lot of the girls have never literally turned a trick. ‘Give away a million before you sell a penny,’ that’s their philosophy. But they don’t know what they’re doing. They don’t think about what’s gonna happen in ten years, because they’re young. They’re short-term survivals.”

Via: Gitterman Gallery, Agents del Mort, Dirty Old Boston

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.