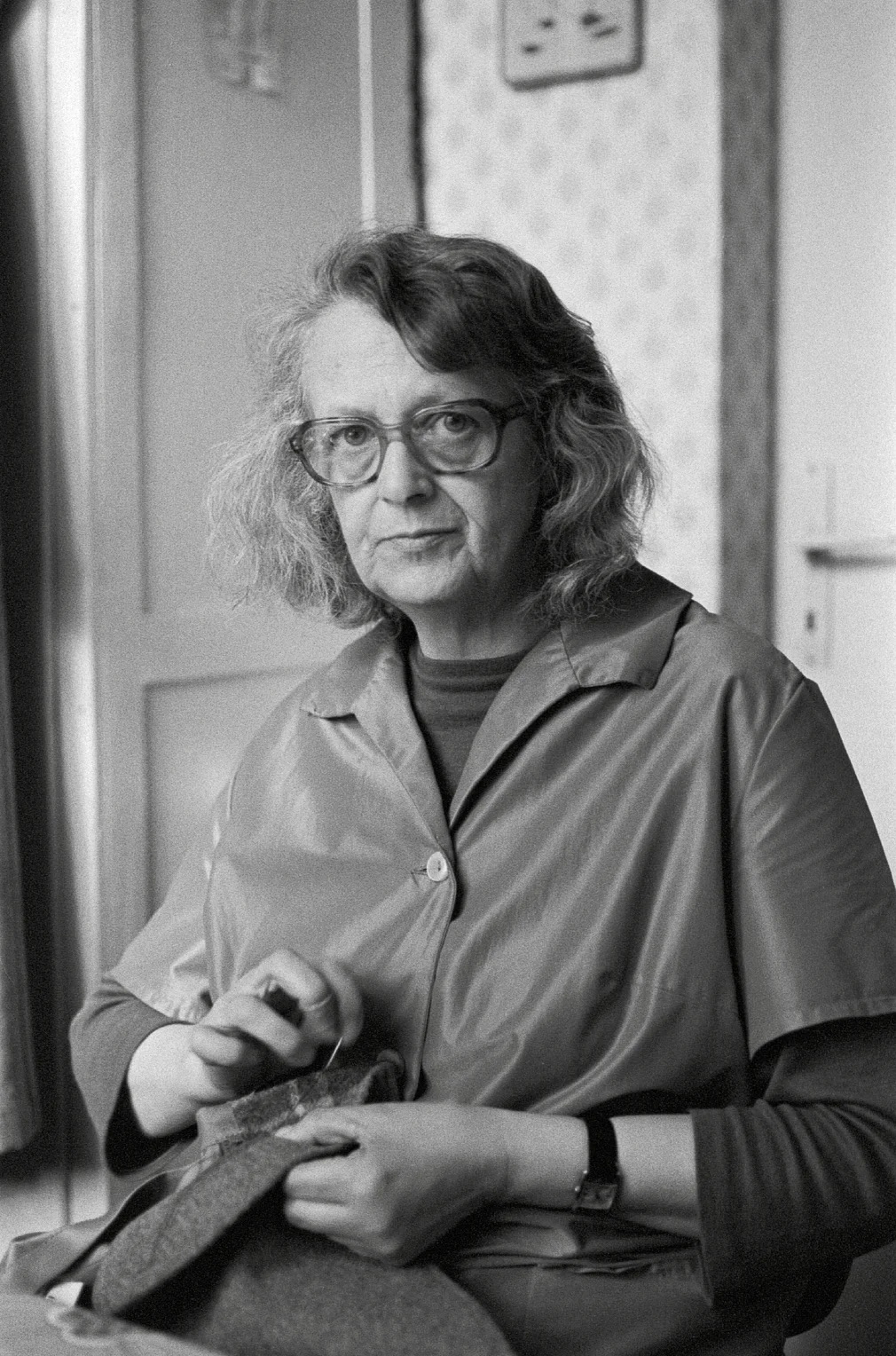

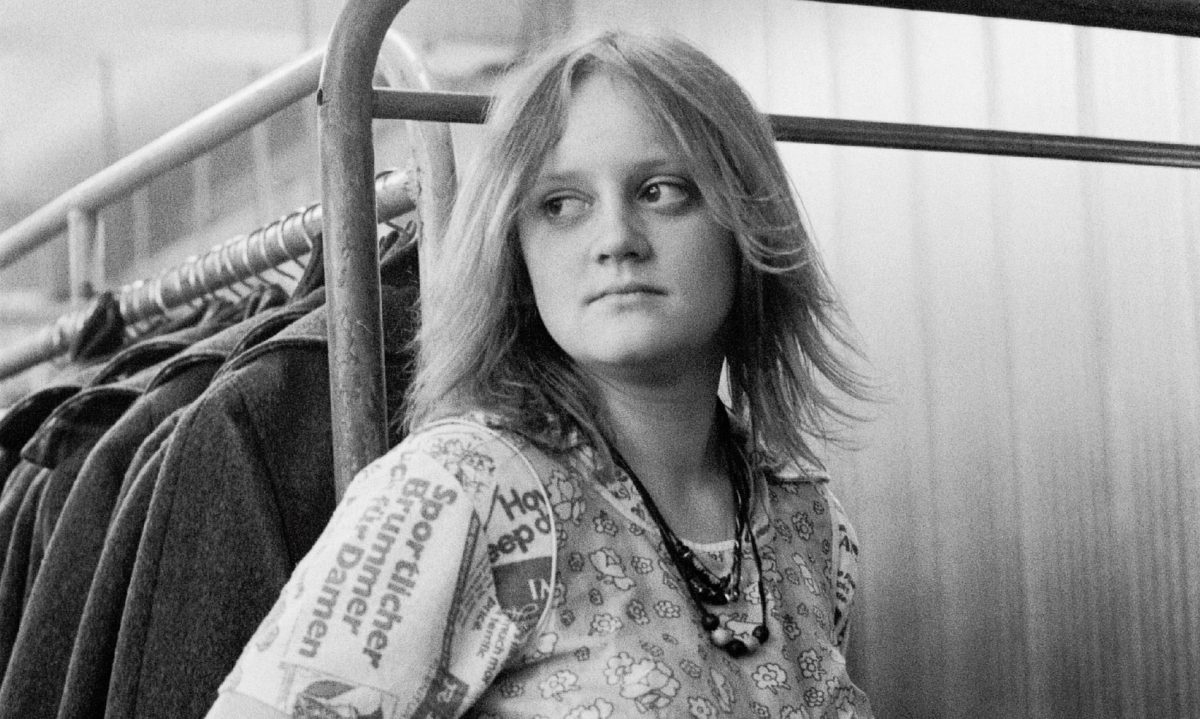

“Every face is an experience; in particular, the rather unremarkable, unattractive ones gain an unforeseen beauty”

– Helga Paris, Women At Work

In 1984, German photographer Helga Paris (21 May 1938 – 5 February 2024) spent several weeks at the state-owned clothing factory VEB Treff-Modelle in East Berlin photographing female employees and their “unforeseen beauty”. Around 50 of the 1,500 pictures she took appear on the book Helga Paris: Women at Work.

As she says:

“Whenever I was at the shopping centre, I looked at the people, watched them closely, imagined how they come home tired from work, before they do this and that. And when the women then stood at the checkout in the usually long line and waited, it all fell away from them and they had a relaxed expression, calm and completely with themselves. Then I thought, I would like to photograph them like that. That was their true face. Of course, that was not possible there in the shopping centre. Then it occurred to me that maybe some of them work nearby in the VEB Treffmodelle Berlin clothing factory.”

“I have always been drawn to the everyday, the unspectacular. But I didn’t photograph it clinically, aseptically; rather, I tried to reproduce it as realistically and as hauntingly as possible. This means that when I photographed women in factories or people on the street, I had to create a certain level of trust in a very short amount of time, where they could meet my gaze with a certain degree of self confidence. Every face is an experience; in particular, the rather unremarkable, unattractive ones gain an unforeseen beauty”

– Helga Paris, Women At Work

“My subjects are people. The need to document everyday life in photographs developed out of necessity. In East Germany, only favourable photographs were shown in the papers and to the public – ideally of the happiest people possible. Real life was hardly ever documented”

– Helga Paris

“In my family, ever since the 1930s, we took a lot of simple photographs: amateurish, small black-and-white photos with scalloped edges. I still have a number of shoeboxes filled with these old pictures from my youth and early childhood. I have these images in my head as well. I think they really made an impression on me. From my study of fashion, I acquired a knowledge of aesthetics and composition, so my self-taught photography skills were able to develop quickly.”

– Helga Paris

“Black-and-white photographs allow more of a look into the details than colour photographs, because the eye can tend to get lost in the contrasts. Black-and-white photographs are more impressive; just by the fine nuances of black, white and especially grey. The composition seems clearer, so you abstract more of what you see, which makes the subject more memorable”

– Helga Paris, Women At Work

“In photography, you need a certain empathy for the other person. Perhaps women have greater empathy here, can develop better and more freely. One must not forget that photography was not really established as an artistic medium at the time. In painting and sculpture, the men often tolerated no one next to them, there was trench warfare. In photography it was different, there was a gender independent collaboration. So photography was a relatively harmless terrain for a woman because of its short tradition” –

Helga Paris: Women at Work

“I had done an internship in the clothing factory during my studies, so I knew many work processes. The project was financed by the Society for Photography in the Cultural Association of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). I was so enthusiastic that I spontaneously sewed on the assembly line myself; some of the women still knew me from my internship days. They were not shy. I asked them to stand or sit somewhere, told them I didn’t expect anything special; they should be as they saw fit. It just had to be quick so they didn’t pose for the camera”

– Helga Paris Women at Work

“From the very beginning, a different self image prevailed in the field of photography. In the west, the new artistic fields such as photography and video were often utilised by women from a feminist perspective. This was different in the GDR. Here, equality prevailed. Women in the garment business worked just as hard as their male colleagues. Feminism sees men as enemies – it’s an ideology. We women in the GDR had nothing against men; on the contrary, we had equal rights. We demanded equal rights when necessary, and we got them. Did that happen in the west? Probably not. That’s embarrassing”

– Helga Paris

“We photographers had more freedom than, for example, the painters and sculptors. At first, we were hardly noticed in the Association of Visual Artists in the GDR; we didn’t even have our own section there at the time. I became a member in 1975 and received a tax number, with which I was – purely legally – entitled to work as a photographer. It was only on the initiative of Arno Fischer and Roger Melis that a working group for photography was set up in the association in the early 1980s. Then we were listened to more.”

– Helga Paris

“Before they thought about how they looked, the shutter was already pressed. So the women were quite unagitated, very matter of fact. They stood according to their function at work, in combination with their respective female self-image”

– Helga Paris

Helga Paris was born in 1938 in what is now the Polish town of Goleniów. She grew up in Zossen near Berlin, studied fashion design and worked as a graphic designer before teaching herself photography in the 1960s. She found inspiration in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg neighbourhood, where she moved in 1966 with her then husband, the painter Ronald Paris, and where their two children grew up.

The moody, sometimes melancholy, works she created in Berlin were strongly influenced by Paris’ surroundings. At the time, the Prenzlauer Berg district was still characterised by working-class families.

Paris was a member of the Berlin’s Akademie der Künste arts academy since 1996. She left her archive of almost 230,000 negatives and around 6,300 films to the art institution.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.