The book began as a catalogue of Bocskay’s skill when in the early 1560s he was working as secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I. It was updated 30 years later when Ferdinand’s grandson, Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, commissioned Hoefnagel to add his watercolour, gold and silver paint, and ink illustrations of flowers, animals, fruit and insects.

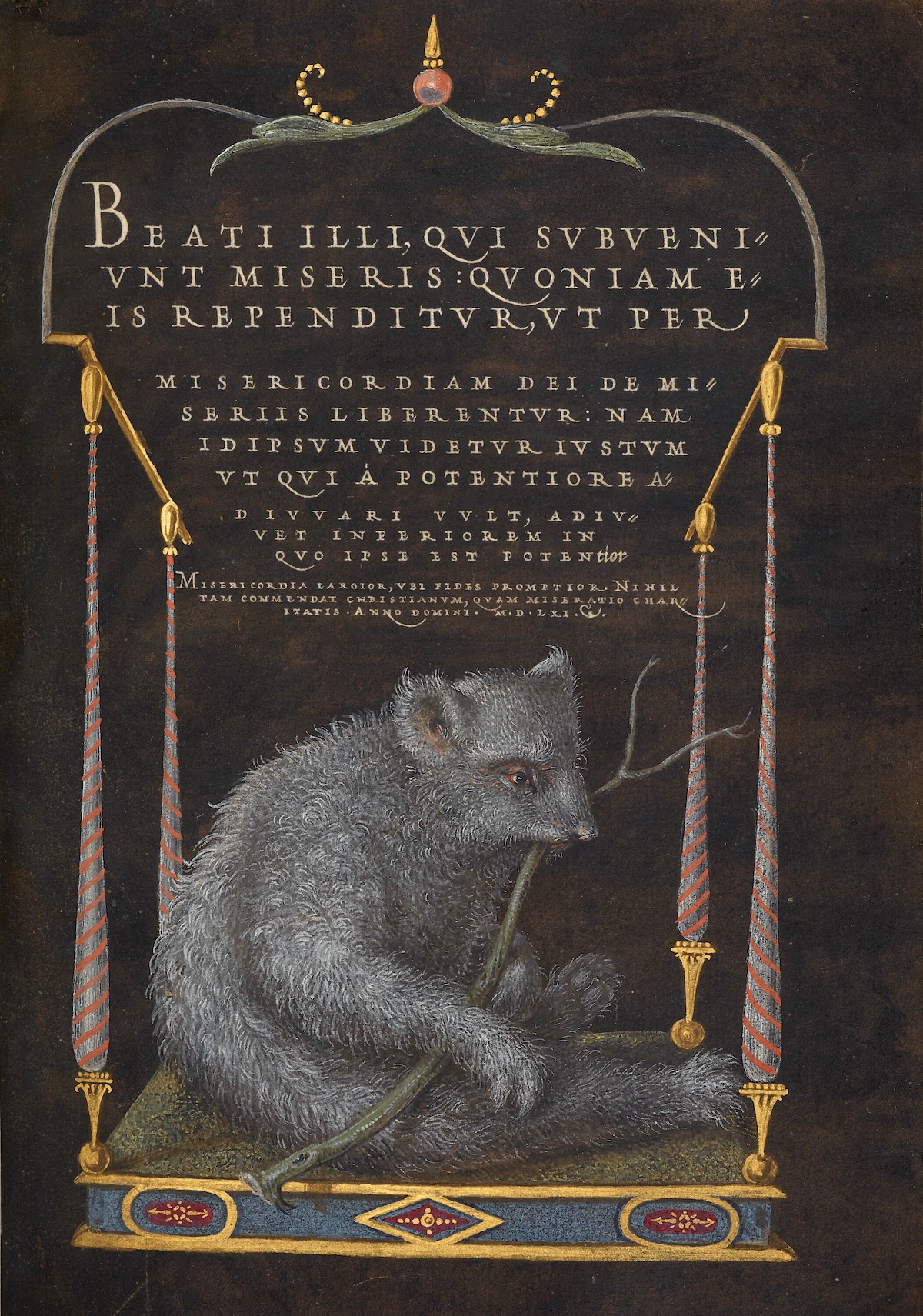

A Sloth by Joris Hoefnagel

Above we see a creature, most likely a sloth, chewing a twig. The Latin text over its head is based on Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. It looks like the page was designed in one go. Things fit. But Georg Bocskay’s writing predates Hoefnagel’s calligraphy by three decades.

The text did originally appear on a plain black background. As Getty notes, Hoefnagel “saw in the diminishing script the suggestion of recession into space, an illusion defied by the two-dimensionality of the text. He thus enclosed the letters within an architectural canopy drawn in perspective. Hoefnagel also responded wittily to the black coloration of the page, interpreting it naturalistically as nighttime: the silvery tones of the animal’s fur and the gold shimmer in the darkness.”

Joris Hoefnagel: The self-taught polymath

Portrait of Joris Hoefnagel, engraving by Jan Sadeler (1592)

Self-taught artist Joris Hoefnagel was a Flemish manuscript illuminator and one of the first artists to work in the new genre of still life. He wrote Latin poetry, spoke several languages, played a variety of musical instruments, and produced topographical drawings, maps, oil paintings and illuminations.

In the late 16th century, Hoefnagel, who had chosen ‘natura magistra’ (nature his teacher) as his motto, created the first illustrated book devoted to the study of insects. Documenting his observations with the naked eye, he meticulously painted realistic images of hundreds of insects in watercolour and gouache.

Deciphering bis work through modern eyes requires a bit of historical context. In 1576, the co-called Spanish Fury saw Spanish forces sack cities in the Low Countries in the years 1572–1579 during the Dutch Revolt. When the Spanish Fury hit Antwerp and his family fortune was plundered by Spanish soldiers, Hoefnagel went into exile.

He found in his insect subjects – “in their capacity for metamorphosis, and in the artifice behind their creation – a reminder that the machinations of human affairs were small compared to the vast and unknowable wonder of divine creation.”

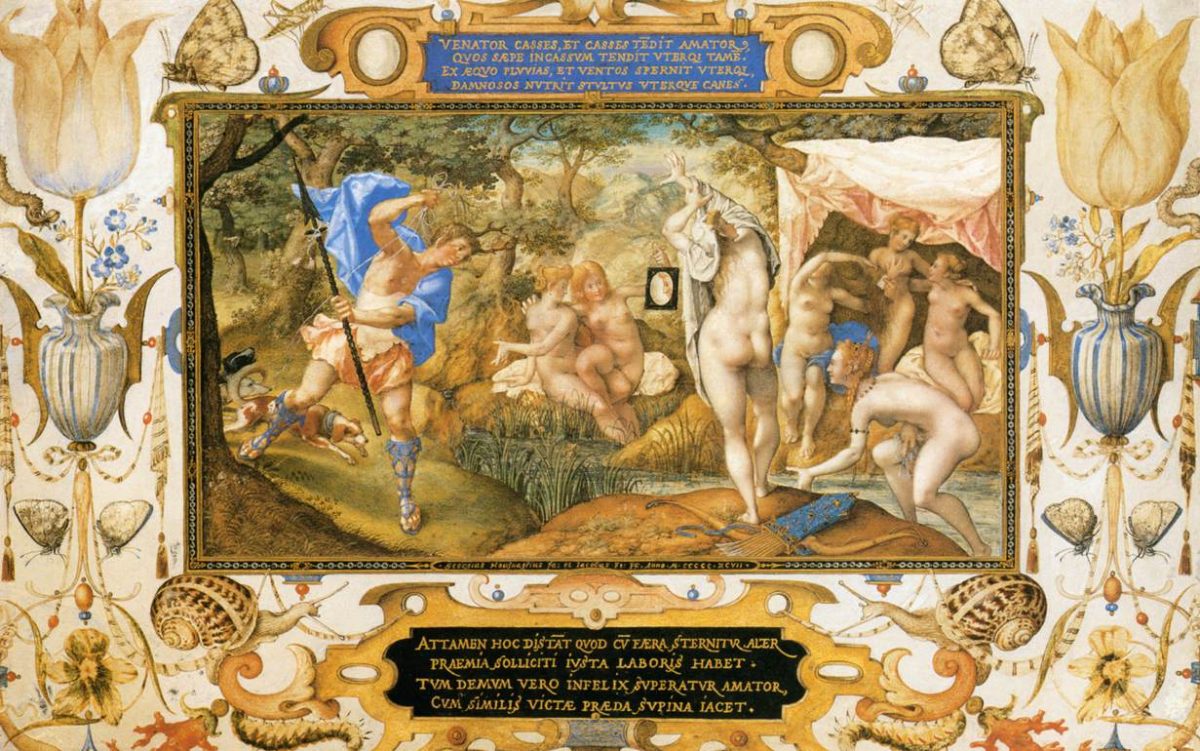

The picture above (Joris Hoefnagel – Venus disarms Amor: 1595) is an odd mix of motifs. The medallion’s subject matter and inscription “Plus aloes quam mellis habent” (They contain more bitterness than sweetness) refers to how earthly love (Amor/Cupid’s arrows) inevitably bring about pain. The inscription at the bottom, “Quatuor in rerum natura elementa” (the four elements of Nature) explains the flowers and fruits (which symbolise earth), butterflies (air), the other insects (fire) and the lobster (water). But, as the National Gallery of Denmark, where you can see the original, says we no longer know the significance of placing “The Four Elements” and “Venus Disarming Amor” within the same context.

Joris and his son Jacob Hoefnagel – Allegory on Life and Death, 1598

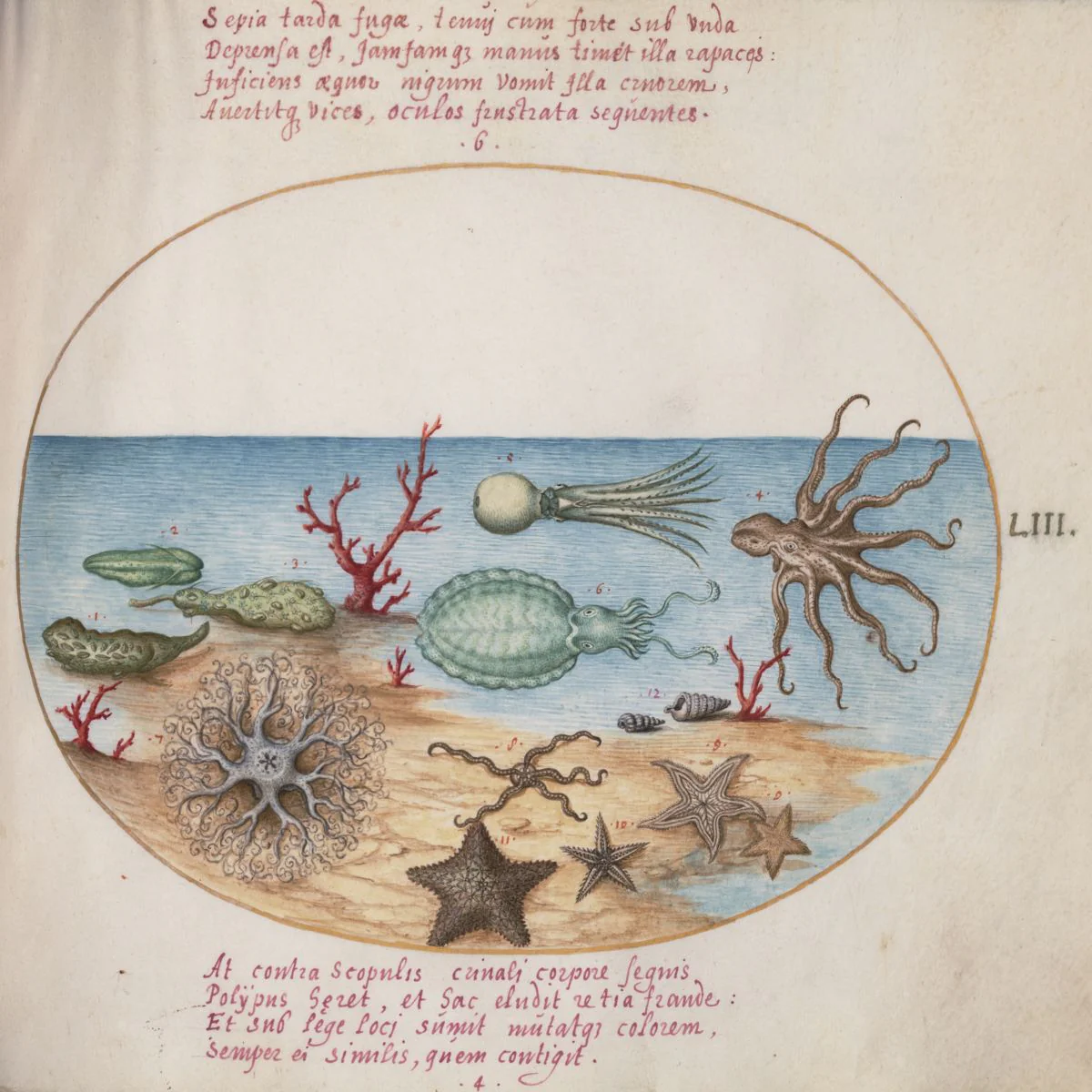

One neglected treasure of the late Renaissance are Hoefnagel’s Four Elements manuscripts, a four-volume manuscript (various folios date from 1575 to 1582). The work was entitled Animalia rationalia et insecta (ignis); Animalia quadrupedia et reptilia (terra) ; Animalia aquatilia et conchiliata (aqua); and Animalia volatilia et amphibia (aier) and contains detailed depictions of thousands of animals, Latin mottoes, epigrams and Bible verses and around 300 illustrations divided according to the four elements.

Writing in Insect Artifice: Nature and Art in the Dutch Revolt, Marisa Anne Bass, associate professor of the history of art at Yale University, investigates how Hoefnagel and his colleagues engaged with natural philosophy as a means to reflect on their experiences of war and exile, and found refuge from the threats of iconoclasm and inquisition in the manuscript medium itself. How his work exists at the intersections between natural history, politics, art and philosophy.

Animalia Aqvatilia et Cochiliata (Aqva) by Joris Hoefnagel c.1575-1580

Working before the invention of the microscope and long before etymology was an established field of study, Hoefnagel produced images that are much more than the sum of his empirical observations. He created his manuscripts not for a wide scientific public but instead for himself and his small circle of friends. These are works that reveal the patient labour of an individual who read and travelled widely, who never stopped asking questions, and who struggled to create in the face of troubled times…

It is crucial to recognize that Hoefnagel’s seemingly perfect painted worlds were created in the very imperfect world indeed – during an era of great social, spiritual, and political discord, and during the decades just before the establishment of the Dutch Republic. The Revolt of the Netherlands was in many ways a conflict much like those that confront us today, conflicts amidst which we too must seek out sites and sources of refuge.

Joris Hoefnagel – Diana and Actaeon, 1597

In his reflections on the chaos of the ongoing war, Hoefnagel turned to the observation of bees, insects which since antiquity had offered compelling metaphors for civil society. Hoefnagel depicts his avian subjects in near symmetry on the page, emphasizing the harmonious communities that they create and presenting a model polity to which humankind might aspire. At the same time, he also acknowledges through an inscription in the margin that even nature’s makers of honey are not altogether peaceful; they too can sting. Hoefnagel’s insects, so he shows us, are not only stunning works of art. They also serve as a reminder of nature’s complexity and of all that it can teach us.

Joris Hoefnagel, Insects, 1597. Watercolor on vellum, Netherlands. Muzeul National Brukenthal

Buy Joris Hoefnagel art in the shop.

Lead image: Poppy Anemones, Caterpillar, Fig, and Quince; Joris Hoefnagel (Flemish / Hungarian, 1542 – 1600), and Georg Bocskay (Hungarian, died 1575); Vienna, Austria; 1561–1562; illumination added 1591–1596; Watercolors, gold and silver paint, and ink on parchment.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.