Reklamemarke Internationale Presse Ausstellung Pressa Published by Köln, 1928 -Illustrator: Ehmcke, Fritz Hellmut

At his peak, El Lissitzky (23 November 1890 – 30 December 1941) was arguably the most renowned artist of the Soviet avant-garde, more so than his friend Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, and Alexander Rodchenko. A trained architect, El Lissitzsky was the artist the USSR’s Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatolii Lunacharskii, would send overseas to show the foreigners how well things were going in the communist empire. In this post, we’ll look at some of that work.

El Lissitzky self-portrait, via The Met, 1924.

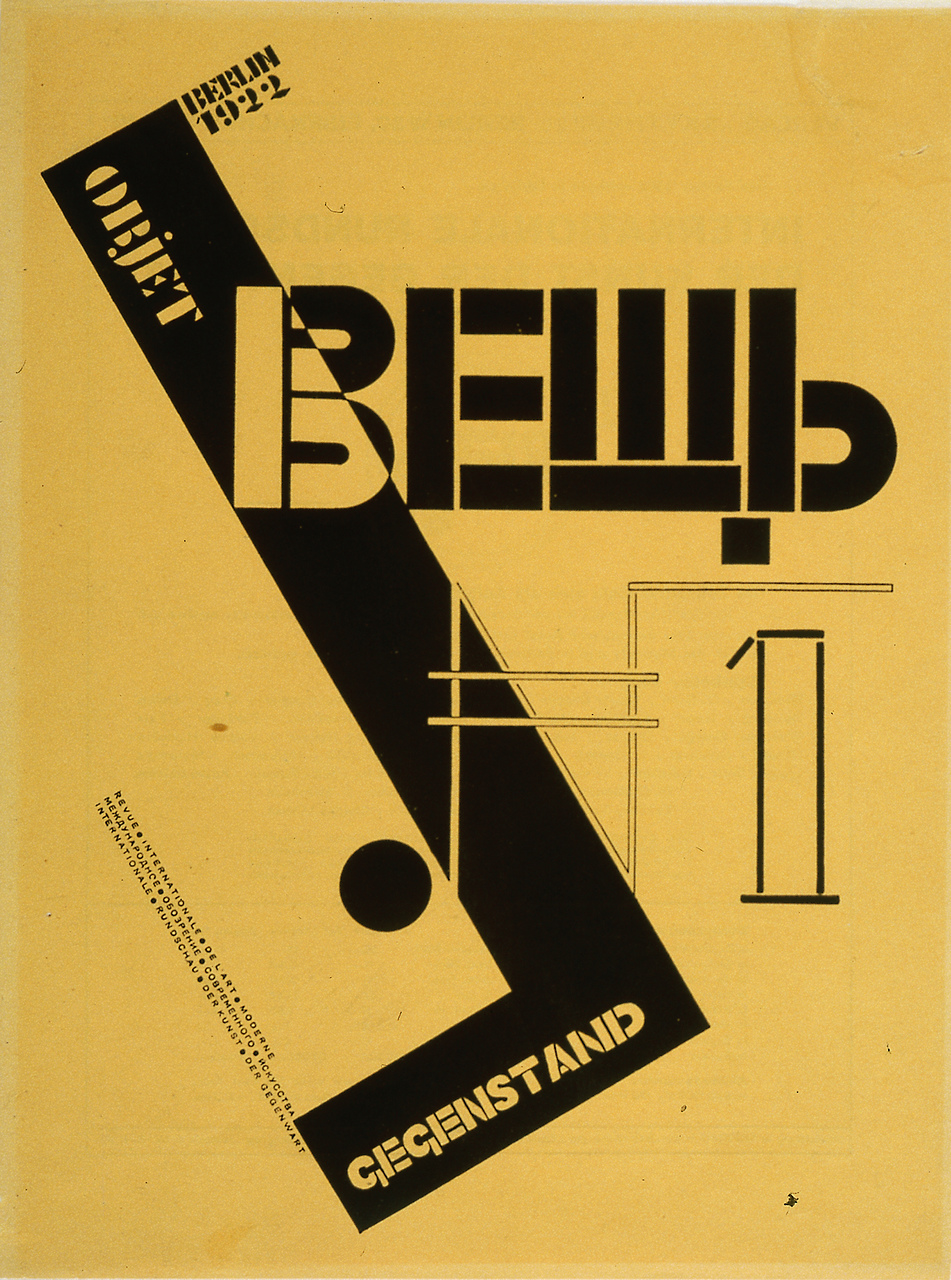

In 1921, Lissitzky was in Germany, working as the Russian cultural ambassador and making connections between Russian and German artists. There he continued his work in book design and journals – he viewed books as “monuments of the future” – and in Berlin created the first issues of the journal Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet in 1922, which he founded together with the writer Ilya Ehrenburh.

The two artists editors explained the journal’s mission to signal how new works of art “make a contribution to life’s organisation”. Lissitzky designed the covers, wrote editorials and selected which artists to show.

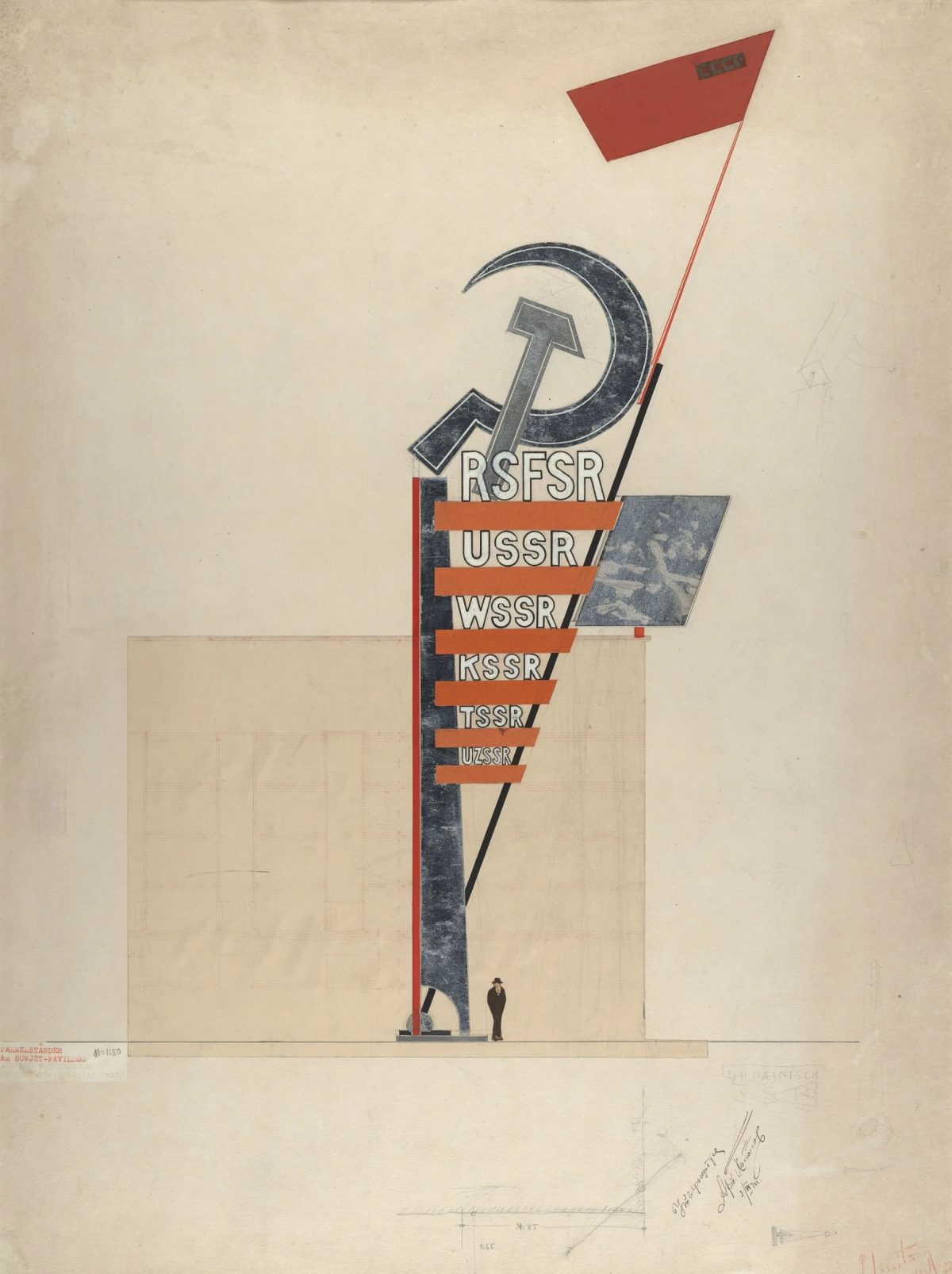

After 1926, Lissitzky designed pavilions for international exhibitions, continuing the work of Konstantin Mel’nikov, whose pavilion from the 1925 Paris Expo was a hit.

“My most important work as an artist began in 1926: the design of exhibition rooms. That year I was asked by the committee of the International Art Exhibition in Dresden to create the room of non-objective art and was sent there by “Voks” [the Soviet commissariat that works with countries abroad]. After an educational trip — the new architecture in Holland being the subject — I returned to Moscow in the autumn.”

— El Lissitzky

Flag the flag of the Soviet pavilion “Pressa” exhibition in Cologne in 1928. View of the Rhine

El Lissitzky, 1928,

Reklamemarke Internationale Presse Ausstellung Pressa Published by Köln, 1928 -Illustrator: Ehmcke, Fritz Hellmut

Lissitzky scored a hit of his own with his display at the 1928 “Pressa” exhibition on global past and present journalism in Cologne. Between 12 May and 14 October 1928 the pavilions of 43 countries and of the League of Nations, and a total of 1,500 exhibitors (among them 450 from outside Germany), attracted more than 5 million visitors.

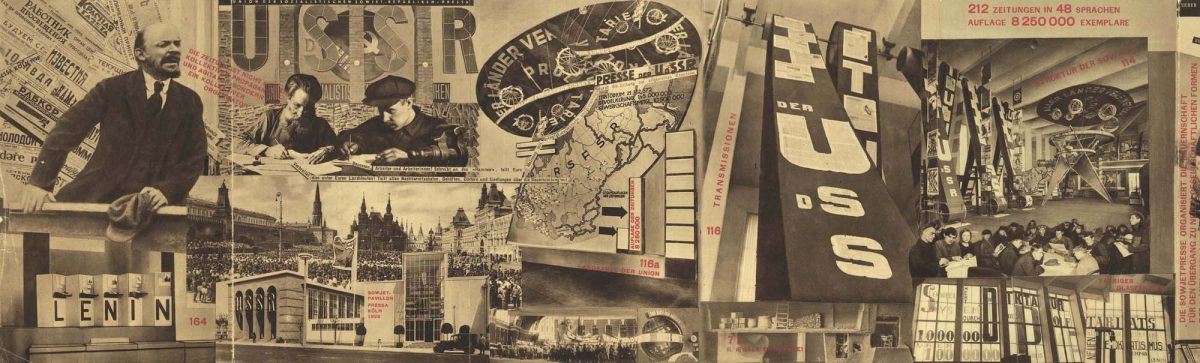

El Lissitzky (1890 1941) and Sergei Senkin (1894 1963). Photomontage from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: Catalogue of the Soviet Pavilion at the International Press Exhibition, Cologne 1928. Photogravure. Buy the print. via

As he wrote:

By state prerogative I was appointed chief artist for the Soviet pavilion at the International Press Exhibition in Cologne. The foreign press praised my design as a great achievement of Soviet culture. For the pavilion I’d designed a photomontage frieze which was 24 meters long and 3.5 meters wide. It became the model for all those gigantic montages, and also a symbol for future exhibitions. I received great accolades from the state for this work. Another part of my duties at the time was the artistic and polygraphic layout of albums, journals etc.

— El Lissitzky (1932)

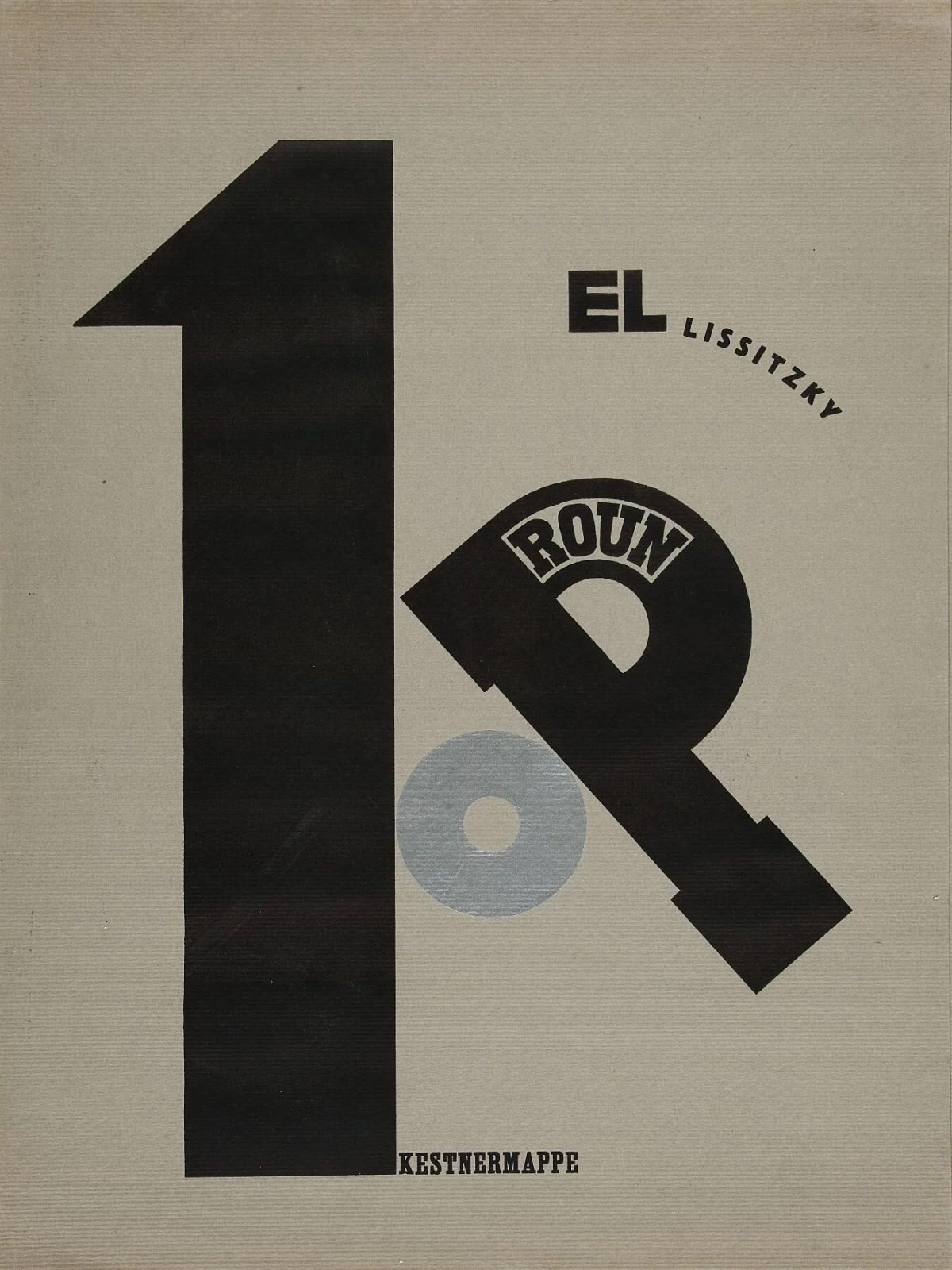

Proun 99 by El Lissitzky – ca. 1923–25

“With Lissitzky, all the possibilities of a new exhibition technique were explored: in place of a tedious succession of framework, containing dull statistics, he produced a new purely visual design of the exhibition space and its contents, by the use of glass, mirrors, celluloid, nickel, and other materials; by contrasting these newfangled materials with wood, lacquer, textiles and photographs; by the use of natural objects instead of pictures… by bringing a dynamic element into the exhibition by means of continuous films, illuminated and intermittent letters and a number of rotating models. The room thus became a sort of stage on which the visitor himself seemed to be one of the players.”

– Jan Tschichold, “Display that has dynamic force: Exhibition rooms by Lissitzky,” Commercial Art (1931)

Buy El Lissitzsky prints, cards and more in the shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.