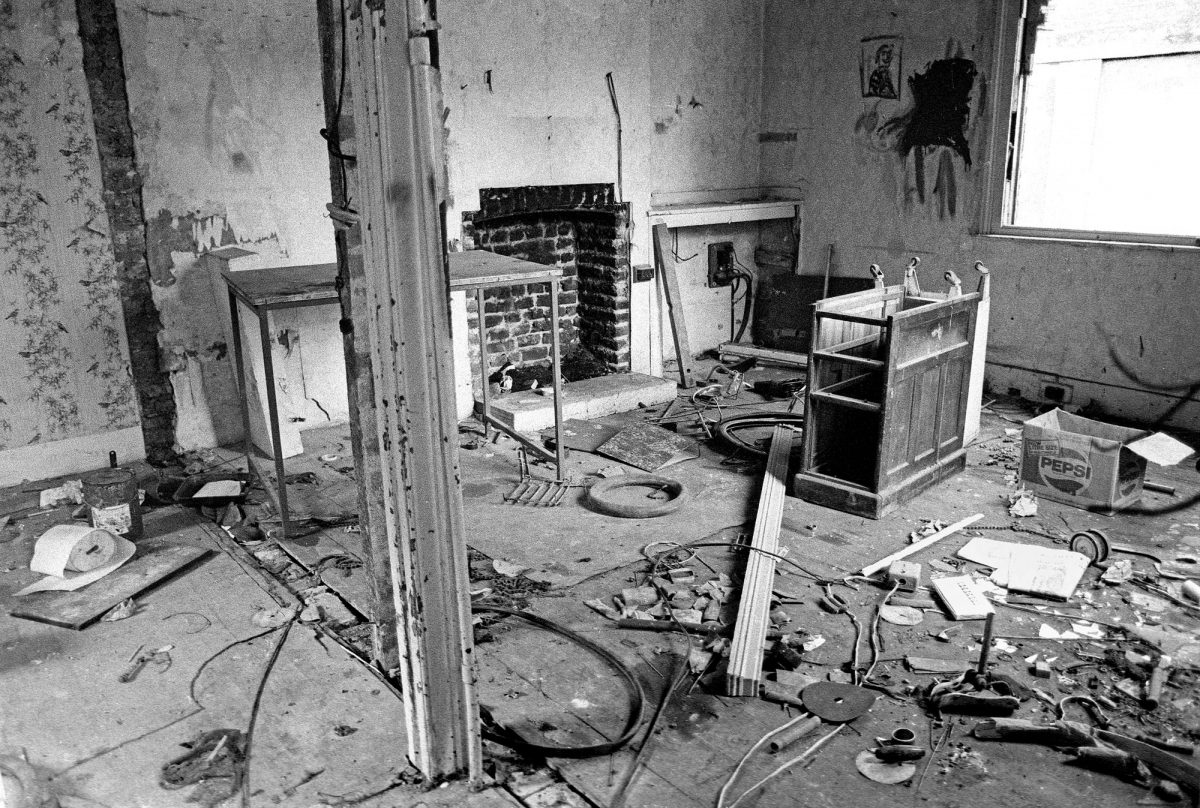

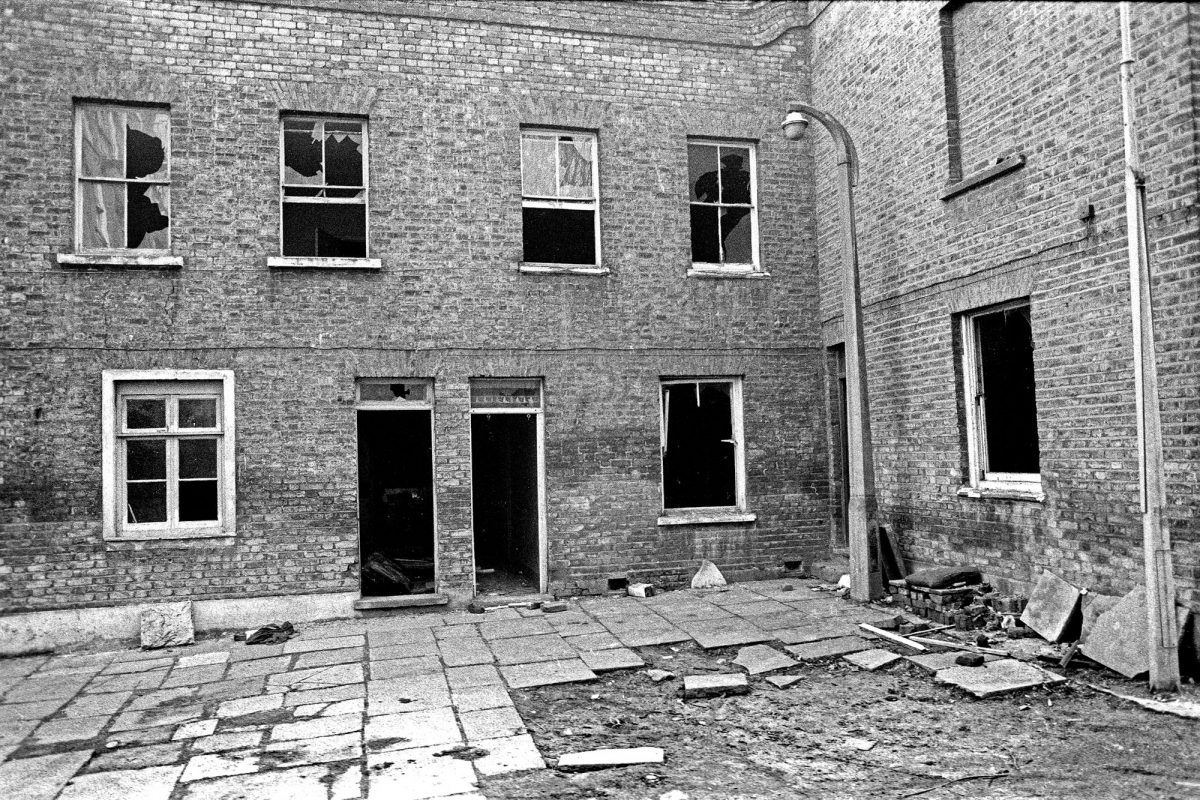

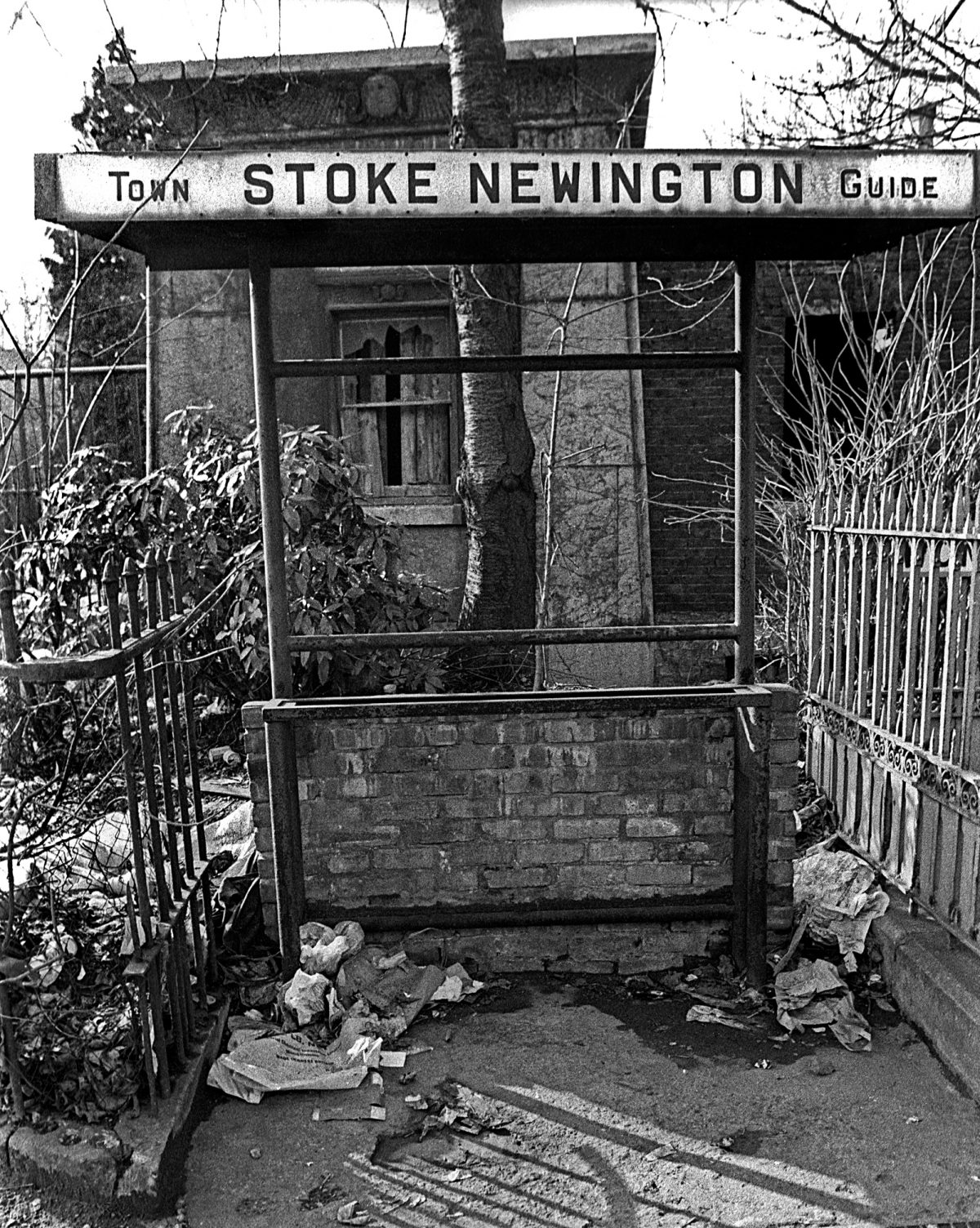

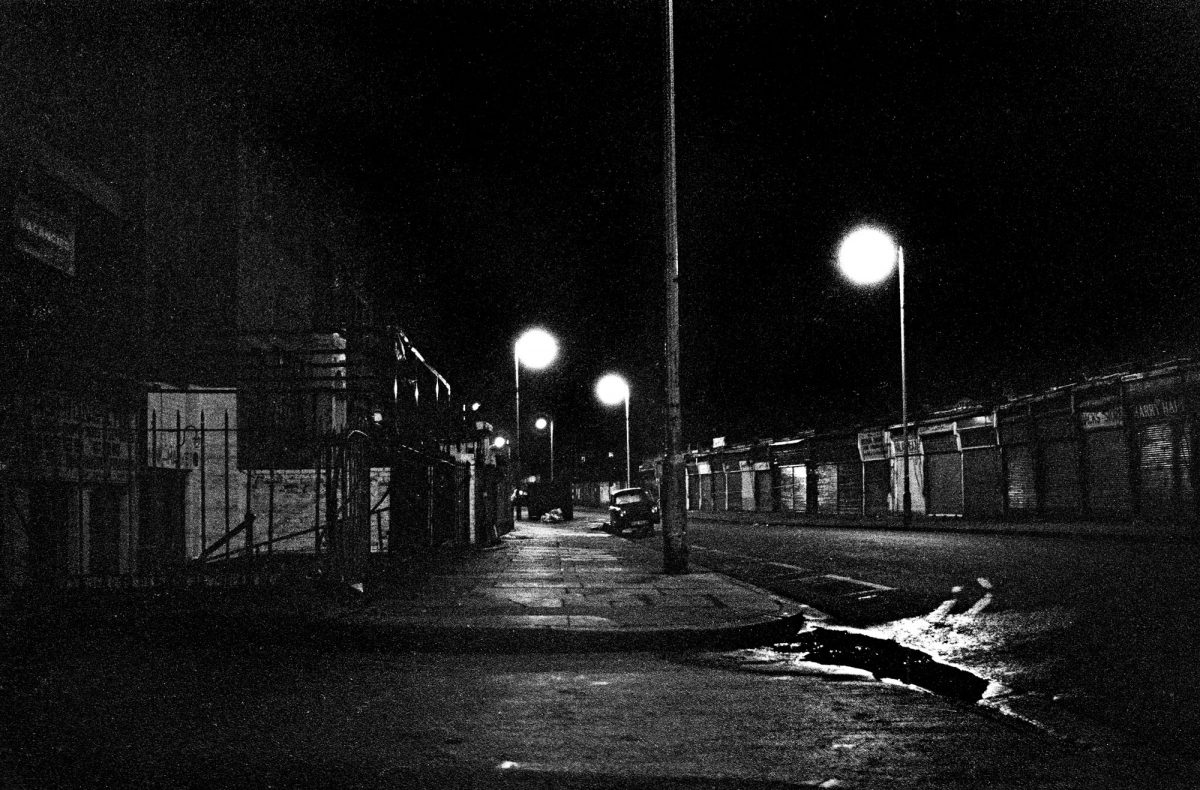

Fifty years ago when Alan Denney went round photographing Stoke Newington during the winter of 1978/79 it almost looked like it had been abandoned. There were rows and rows of decaying, poorly-maintained Victorian houses many of them empty. If you stroll along Stoke Newington High Street or Church Street today it’s Foxtons, Planet Organic, Whole Foods and Jojo Maman Bébé but fifty years ago there were just innumerable empty shops many of them faced with graffitied corrugated iron.

It was the coldest winter for sixteen years and is still remembered as ‘the winter of discontent’ – from the famous first line from Shakespeare’s Richard III. It wasn’t the freezing weather of course that gave that winter its name, although it couldn’t have helped, it was the many months of industrial unrest that almost certainly brought about the end of James Callaghan’s Labour government that spring. Callaghan had been expected to hold the election the previous October but fatefully decided to postpone until May hoping that the economy would stabilise.

In August 1975 inflation had reached a height of nearly 26.9% – a rate almost inconceivable to most of us today. Not surprisingly it affected nearly everything the Government tried to do to bring Britain’s economy back on track. The Prime Minister of the time, Harold Wilson, Callaghan’s predecessor, while wanting to bring inflation under control also wanted to avoid high levels of unemployment. A voluntary incomes policy was agreed with the TUC designed to cap any pay increases to limits set by the government.

By 1978 the rate of inflation had halved but the government, now led by James Callaghan after Harold Wilson’s sudden resignation in 1976, thought it still prudent to constrain wages and decided to continue with the incomes policy. Expecting pay restraints to end a surprised TUC overwhelmingly rejected the government’s 5% limit and demanded the immediate return to free collective bargaining.

Stoke Newington High Street 1979

In September 1978 Ford motors set a pay increase of the government approved 5% – an amount immediately rejected by their workers. Soon 57,000 Ford workers were on strike. A relatively weak Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU), afraid of the rank and file control over the strike, made it official in October. The shop stewards demanded a 25% pay increase but after negotiations between the TGWU and Ford a pay increase of 17% was agreed. The government attempted to sanction Ford for the breach of the pay policy but after narrowly avoiding losing a vote of no confidence accepted that no sanctions could realistically be imposed on Ford. This meant that the government had no way of enforcing its pay policy,and unions which had not yet put in pay claims, began to twitch.

The next to take action were lorry drivers who followed the BP and Esso tanker drivers who refused to work overtime in support of a 40% pay increase, all went on strike in January 1979. Thousands of petrol stations were closed and drivers picketed firms that still had lorries on the road. After just over three weeks the drivers accepted a pay deal of just £1 less than the Unions had asked for.

By now the public sector workers were determined to keep up with the wage increases of their counterparts in the private sector. Gravediggers, notably, went on strike in Liverpool the council even considered telling the public that they could use the municipal cemeteries but only if they made “their own arrangements for grave digging”. Whitehall considered bringing in private contractors and even troops but the thought of ‘unseemly scenes’ at cemetery gates quickly halted that idea.

On January 22 1979 there was a “Day of Action” held by public sector unions and 1.5 million workers went on strike. It was the largest general stoppage of work in the UK since the General Strike of 1926. There was a demonstration of 140,000 people in London alone. Many workers remained out on strike indefinitely including the waste collection workers with many local councils running out of space to store waste. The sight of rubbish piles building up around the country On February 21 the workers accepted a 11% increase and went back to work.

Stoke Newington High Street 1979

Stoke Newington Commo

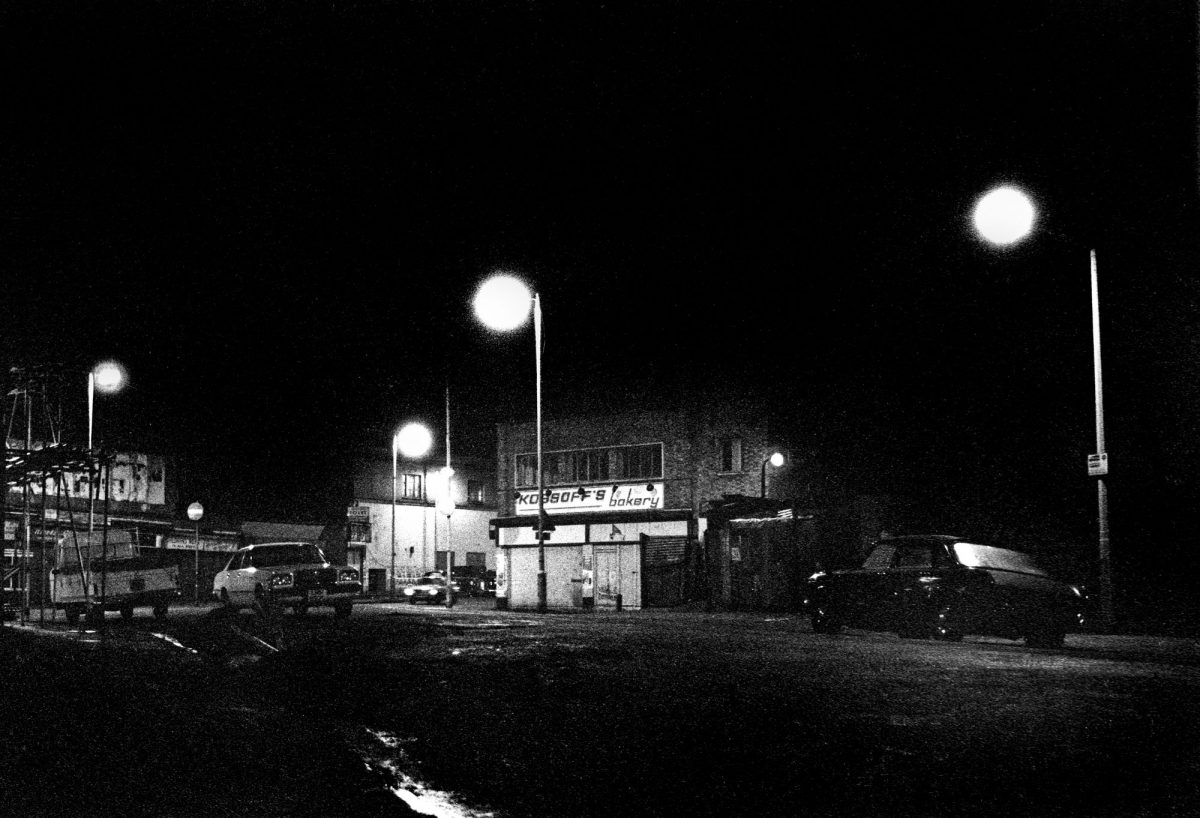

Dalston Junction Station 1979 The large building beyond the station was the Dalston Theatre home of the Four Aces Club

Ridley Road 1979

Ridley Road 1979

The strikes, following an agreement with the TUC and the government after weeks of negotiation, should have ended on February 14. Many of the Unions, however, had relatively little control over their members at the time and many of the strikes continued to the end of February. In the end 29,474,000 working days had been lost.

On the 28th March, 1979 James Callaghan lost a parliamentary vote of confidence by a minority of one. When the result was announced the Tory MPs cheered jubilantly while the Labour MPs tried to drown them by sombrely standing and singing the Red Flag. It meant that Callaghan was the first Prime Minister since Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 to be forced into an election by the chamber.

Ironically in 1969 Callaghan had led a cabinet revolt which led to the abandonment of a proposed reform of trade union law outlined in a Barbara Castle white paper called ‘In Place of Strife’. Had Castle’s white paper been implemented, most of the action during the Winter of Discontent would have been illegal.

On the 4 May 1979 Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister…

That didn’t go down well with Alan Denney who once said: “I just thought it was important to photograph these things, and hopefully make people so angry that they’d rise up and defeat capitalism. Well, that didn’t happen, but I still think it’s important to maintain a critical stance towards capitalism. It’s clearly not meeting people’s needs. It’s giving us war, poverty, ill health, damaging our planet. We need to be angry about that, but unfortunately people in the West seem reasonably content.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.