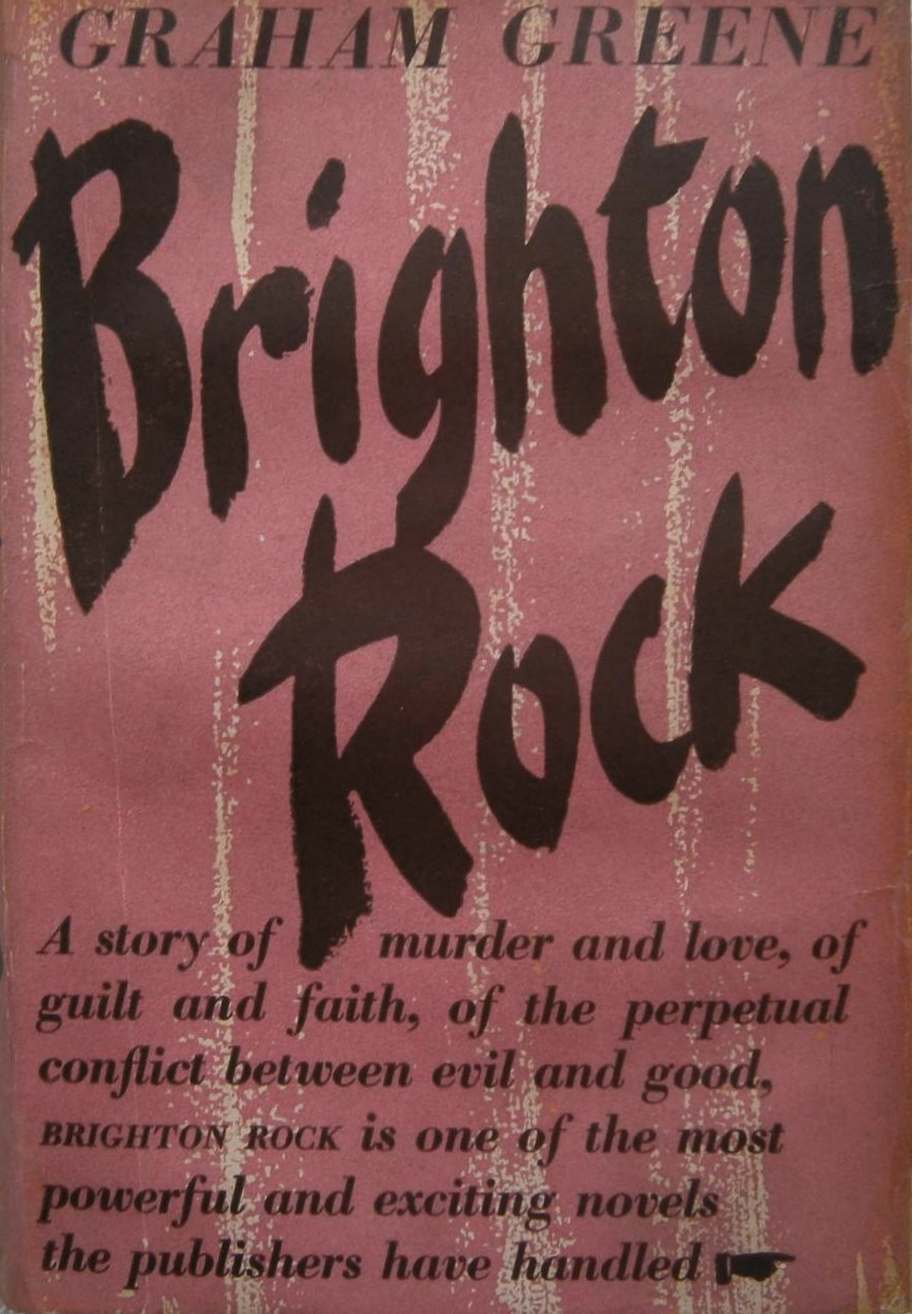

In January 1948 the Observer film critic, C.A. Lejeune, made no attempt to hide her disapproving tone when reviewing the Boulting Brothers’ Brighton Rock: “Graham Greene’s savage story about a couple of race-course gangs and their fancy ways with a razor is one of the most brutal things I have seen on the screen…” Reg Whitley in the Daily Mirror joined in with the disapproval but his distaste was not just with Brighton Rock but with the whole of the growing genre of British crime thrillers. Under the headline ‘WHY STAR THE SPIVS’ he wrote “We are in for a real basinful of British pictures about spivs, smash-and-grab raids and West-End “wide boys,” with a bunch of grim murder dramas thrown in as light relief”.

Before WW2, unless you associated with the south London criminal fraternity, the word Spiv was almost unknown (it has again slipped out of general use except by Vince Cable). It meant a man who worked the fringes of the underworld – a small time crook, a con-man or a fence rather than a full-time and dangerous villain but the exact origin of the word is lost in the mist of villains’ cant. The word is as etymologically obscure as the provenance of the goods the spivs were trying to sell. By the end of the war, however, the use of the word and the men it described were everywhere.

It was presumably a surprise to Bill Naughton, the playwright and author brought up in Bolton but best known for his London play and subsequent film Alfie, that a word used in the title of an article he wrote in September 1945 would go on to become such a linguistic phenomenon. Written for the News Chronicle, just a few weeks after the end of WW2, Naughton’s article “Meet the Spiv” began:

“Londoners and other city dwellers will recognize him, so will many city magistrates – the slick, flashy, nimble-witted tough, talking sharp slang from the corner of the mouth. He is a sinister by-product of big-city civilisation – counterpart to the zoot-suited youths of America.”

One theory about ‘spiv’ is that it could well have come from the slang term ’spiff’ meaning a well-dressed man. This turned into ’spiffy’ meaning spruced-up and if you were ‘spiffed up’ you were dressed smartly. Over time the two meanings of ‘spiv’ seemed to have mysteriously combined to produce a smartly dressed small-time criminal, and when Bill Naughton prominently used it in 1945, the word caught the imagination of the public of all classes. Everyone latched onto the catch-all label that was sorely needed for the huge number of smartly-dressed men living by their wits selling ration coupons, scarce goods and sought-after luxuries during and after the war.

The presence of the ‘slick, flashy’ Spivs gave post-war British cinema an excuse to make their own version of the 1930s Hollywood gangster movies – still loved and regularly watched by much of the UK cinema audiences after the war. The cinematic spiv clothing and manner – bright ostentatious ties, striped shirts worn with well-cut suits with wide lapels – were themselves based on clothes worn by Jimmy Cagney, Edward G Robinson et al. To British audiences these clothes also stood out by being the antithesis of the three-sizes-fits-all de-mob suits presented to each and every serviceman after the war.

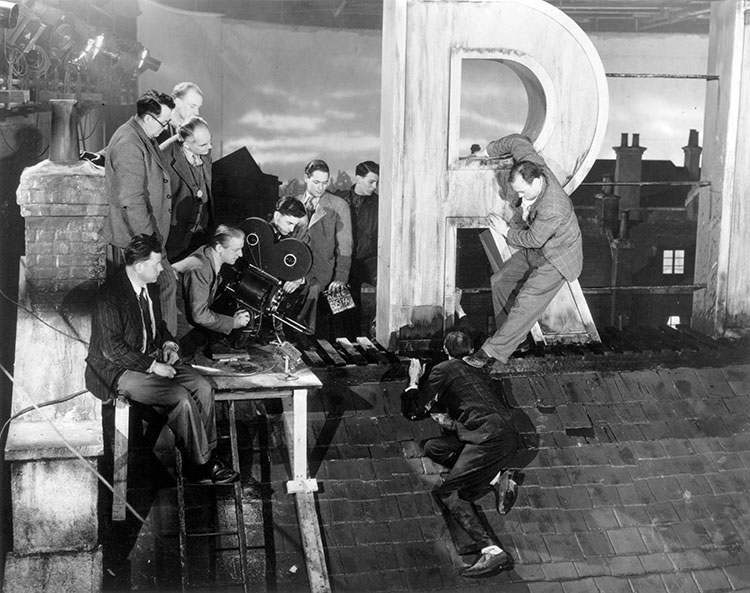

Richard Attenborough on the set of Brighton Rock in 1947. The clothes worn in the film by Pinkie, played by Richard Attenborough, were nothing but the classic ’spiv’ uniform, although in the novel, set in the thirties’ depression years, Greene described Pinkie’s frayed tie and emphasised the general shabbiness of the clothes.

‘Brighton Rock on paper is a work so sordid, so dusty with decay and smelling of evil as to be untranslatable in completely human terms. It’s characters are despicable – almost to a man or woman.’ Wrote Picture Post in 1943 about the play, also starring Richard Attenborough, at the Garrick Theatre.

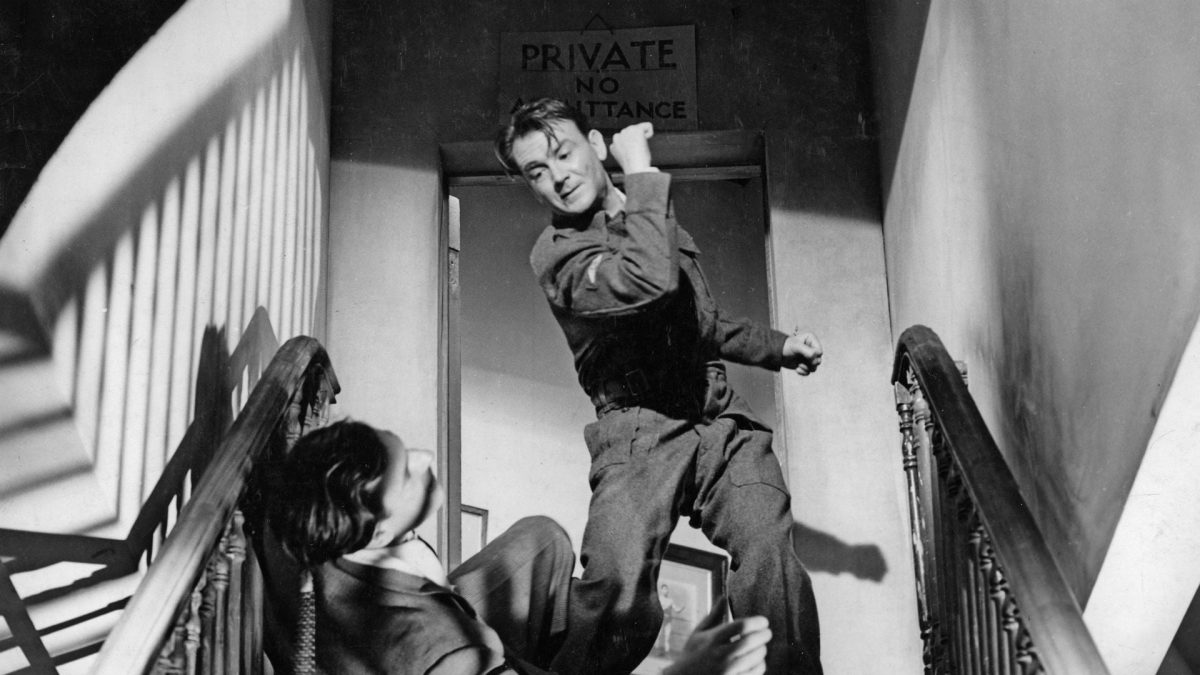

John Mills in Waterloo Road

There had been attempts before to copy the American gangster films but the pre-war censors clamped down on this immediately. After 1945 it was a different matter, post-war confusion and changes in the makeup of the British Board of Film Censors made it far easier for the Spiv films to get past the relatively feeble attempts of censorship. The historian James Chapman wrote:

While the new regime may not necessarily have been more liberal in outlook than their predecessors…the turnover in Board members after the war gave rise to a period of instability during which the board’s policies were applied less consistently than before.” This was despite the head of the BBFC Andrew Harris calling the ’spiv cycle’ films ‘pseudo-American”, “Hollywood at its worst” and “technically bad”.

The contemporary reviewers didn’t call him such but cinema’s first proper movie Spiv probably appeared in the often forgotten Waterloo Road. Made towards the end of 1944 and directed by Sidney Gilliat it starred John Mills and Stewart Granger and was filmed on location in what was then a working-class district around the famous south London station. Mills, nearly always shown as the embodiment of an unwearying British decency played an honest soldier called Jim Colter who is forced to go AWOL, or in the parlance of the newspapers at the time ‘take French Leave’, after hearing rumours that his wayward wife is seeing the local greasy, flashy pin-table king and marketeer Ted Purvis.

The wartime critics almost universally praised Waterloo Road and it was seen by most of them as an accurate portrayal of working-class London life; “Acted with such sincerity and is so true-to-life in its characterisations that the picture grips throughout,” wrote Variety.

The story of a couple not only struggling to cope with being separated for months but also with the chance that they’ll never see each other again would have chimed with much of the film’s audience. The strain on marriages during the war was severe but Waterloo Road also reflected how utterly exhausted people were becoming as the end of the war was approaching. During a flashback early in the film we see a conversation between Colter and his wife, Tillie played by Joy Shelton, who’s exasperated and drained from living in an over-crowded house with her husband’s family:

Tillie: Oh I don’t know what I want.

Jim: You’re right there, and no mistake. The moon I should think.

Tillie: Well, I don’t look like I’m getting it do I? I’m sick and tired of this sort of life, if you want to know? Not doing this, and not doing that, just because of the war.

Mary Ferguson in her Home Service column in the Daily Mirror praised Waterloo Road as: ‘Good entertainment with richly human Cockney touches’.On the same page she brusquely criticises some Land Girls, fourteen of whom had written to Ferguson complaining about their lack of leave to see their boyfriends back home from the front:

No woman in war work gets extra leave when her sweetheart comes home, wrote Ferguson, Sweethearts don’t count this time. Women in war work who do get extra leave without pay, over and above their paid annual holidays and bank holidays, are the wives of serving men. If all the girls with boyfriends in the Services got leave every time the boys came home it would be a poor look-out for the war effort.

Meanwhile Jim Colter, still on ‘French leave’ and successfully avoiding the Military Police with the help of a sympathetically portrayed Canadian deserter, is still in search of his wife. He visits the local hairdressing salon where he speaks to Ted’s world-weary ex-girlfriend and asks if she knows of Ted and Tillie’s whereabouts:

Okay, now let’s see. Ted might have taken her to the dogs, only there’s no dogs today, he might be at the pictures picking up a few hints from Victor Mature, or he might be at the Alcazar, jitterbugging. I think that about covers his war effort.

The behaviour of Stewart Granger’s immoral ‘spiv’ character was notably left generally uncriticised by the contemporary film critics. Though the fact that Ted Purvis was played with undoubted charm by the Kensington-born thirty-one year old Granger may have had something to do with it: “the most sensational screen discovery of the war. Undoubtedly the No. 1 heart throb of the moment” enthused the Daily Mirror Film Critic Reg Whitley (as yet not on his high-horse about the portrayal of spivs in home-grown cinema).

Many women sitting in the cinemas up and down the country would have sympathised with Tillie Colter’s confusion about being simultaneously attracted to and yet repelled by the sweet-talking handsome spiv offering her compliments and black-market gin while her husband was away for months at a time. The empathy felt for Ted in Waterloo Road, however, went further than this. In 1945 the great majority of the the law-abiding population, or at least those who considered themselves law-abiding, found that without the black market and the spivs, it was almost impossible to have any quality of life at all. To a worn-out and spent Britain, it often seemed only the Spivs could offer an escape from the grim and suffocating austerity.

By 1946 the British government were beginning to be worried with the public’s sympathy and patience with the pervasive spivs. In November that year the journalist Warwick Charlton reflected this in an article for the Daily Express:

The spivs’ shoulders are better upholstered than they have ever been before. Their voices are more knowing, winks more cunning, rolls (of bank-notes) fatter, patent shoes more shiny. The spivs are the “bright boys” who live on their wits. They have only one law: Thou shalt not do an honest day’s work. They have never been known to break this law.

A few months later in 1947 Mr Frederick Lee Labour MP for Manchester Hulme in a debate about the Economic Situation brought up the subject of spivs:

I do not know whether the word “spivs” is a Parliamentary expression, but it seems to me that in these days we are suffering from a curse of “spivs” that have never found, and do not want to find, a method of getting anything without working for it. It seems to me, however, that a very large number of people in the gaming saloons one can see around London are getting “a very good living, thank you” without much thought or work.

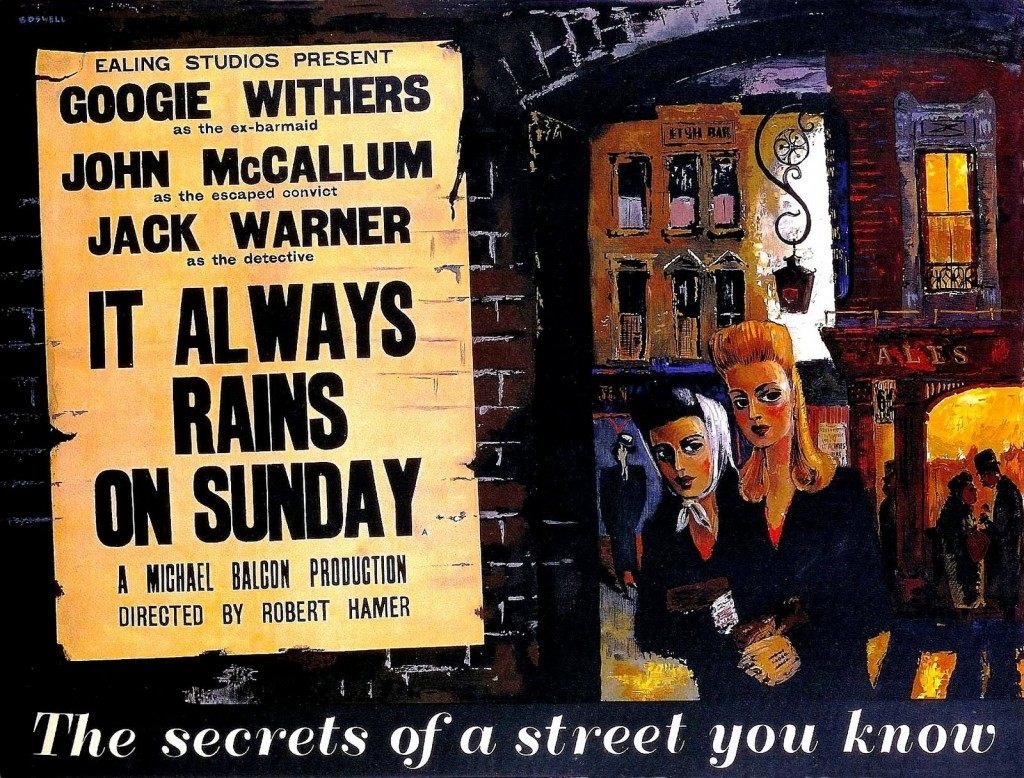

The Daily Express film critic Leonard Mosley in November 1947 asked whether there had ever been “a more depressing title than “It Always Rains on Sunday” which is the name some damp-minded genius has given to the new film which had its premiere last night at the Odeon, Leicester Square?”

The ‘damp-minded genius’ director Robert Hamer and his Bethnal Green-set film was indeed a rain-drenched, desolate melodrama and set during one 24 hour Sunday. Mosley liked it though and as with most reviewers of the time spoke without criticism the spivs featured in the movie saying that “they all add flavour to a big broth of a film.” In a film peopled by the immoral and the dissolute (at one point a lorry driver, while maintaining small-time fiddling himself, moans about the dishonesty of everyone else – “you never know who’s up to what these days!”) the main scheming spiv-character in the film Lou Hyams (John Slater) is shown in a particularly sympathetic even generous light. He’s shown for instance giving away as a present the goods he has acquired by nefarious means: “Here, I’ve brought her some stuffed olives. Put them under the counter, that’s where they came from!”

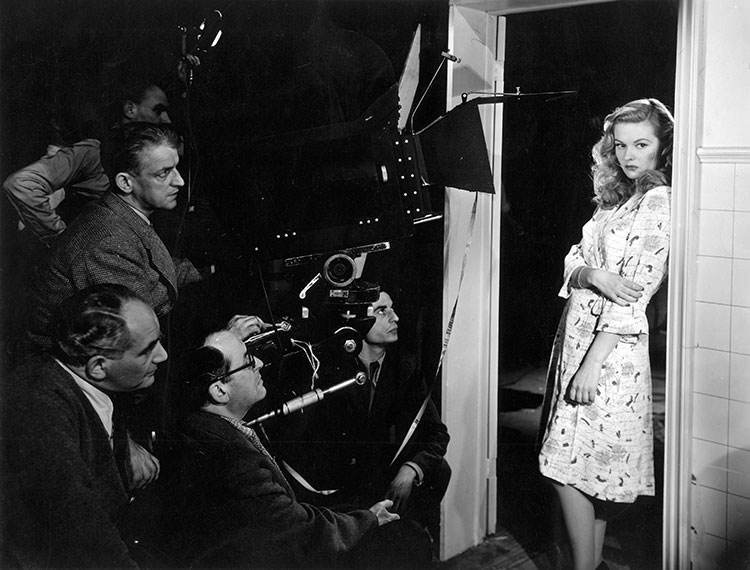

John McCallum, Patricia Plunkett (stepdaughter Doris) and Googie Withers in Robert Hamer’s IT ALWAYS RAINS ON SUNDAY (1947)

Robert Hamer directing Googie Withers and John McCallum in It Always Rains on Sunday. The leading couple would get married the following year.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGDaTnVUKIg

The Cinematograph Exhibitors Association reflected closer the attitude of the Government when they described It Always Rains on Sunday as “an unsavoury film… with appeal only to those with very broad minds.” Perhaps not surprisingly just two years after the war but there must have been a lot of broad minds – the Ealing film was the hit of the year.

They Made me a Fugitive

As we have seen the Daily Mirror critic Reg Whiteley was no fan of the ‘spivs’ genre:

I have just seen the first of the Soho spiv epics: They Made Me a Fugitive” – a sinister yearn about an ex-RAF boy who finds Civvy Street too dull and takes to crime for excitement.

The picture is dramatic, and extremely well made. I admit some may regard it as exciting entertainment, but it worries me. I’m worried about the moral effect to the near sixteens of the flood of pictures of this type…I am no killjoy, but I think the Censor should keep a watchful eye on the increasing number of films dramatising crime. They provide much ammunition for the anti-cinema brigade, who are only too pleased to blame the pictures for the misdeeds of youth.

In a similar way to John Mills, Trevor Howard was nearly always a shining icon of British decency, albeit slightly more posh and when he showed up as unshaven anti-hero Clem Morgan in They Made Me a Fugitive, one knew that there was something rotten in post-war British society. The film was shot in the noir style by Otto Heller who was also the cinematographer of Peeping Tom (incidentally C.A. Lejeune of the Observer was so disgusted with Michael Powell’s 1960 film she resigned as the newspaper’s film critic). British film-noir was subtly different from its American cousin – as someone once wrote: “think damp cobblestones rather than hot asphalt” but the British films also had a post-war melancholy that mirrored how the country felt after the short-lived joy of what seemed an anti-climatic victory over the Nazis.

Trevor Howard’s Clem Morgan despite ‘a fine war-record’ finds ‘civvy street’ tedious and dulls it by turning to drink. At the toss of a coin he joins a criminal gang led by Griffith Jones’s Narcy who is described as “not even a respectable crook, just cheap, rotten after the war trash.” Many in the audience would have recognised Clem’s listless confusion after the ‘excitement’ of the war and sympathy would have been retained while the criminality is initially shown as the typical spivs variety – essentially smuggling luxury and rationed goods such as cigarettes, alcohol and New Zealand lamb.

Morgan isn’t completely immoral and he can’t hide his disapproval of the gang’s involvement in smuggling drugs (‘sherbet’) – in other words un-spiv-like proper villainous activity. Crossing Narcy he gets himself framed for the murder of a policeman and sent to jail. He escapes from captivity – “the whole damn world and its dog are after my skin” he says and thus becomes the fugitive of the title.

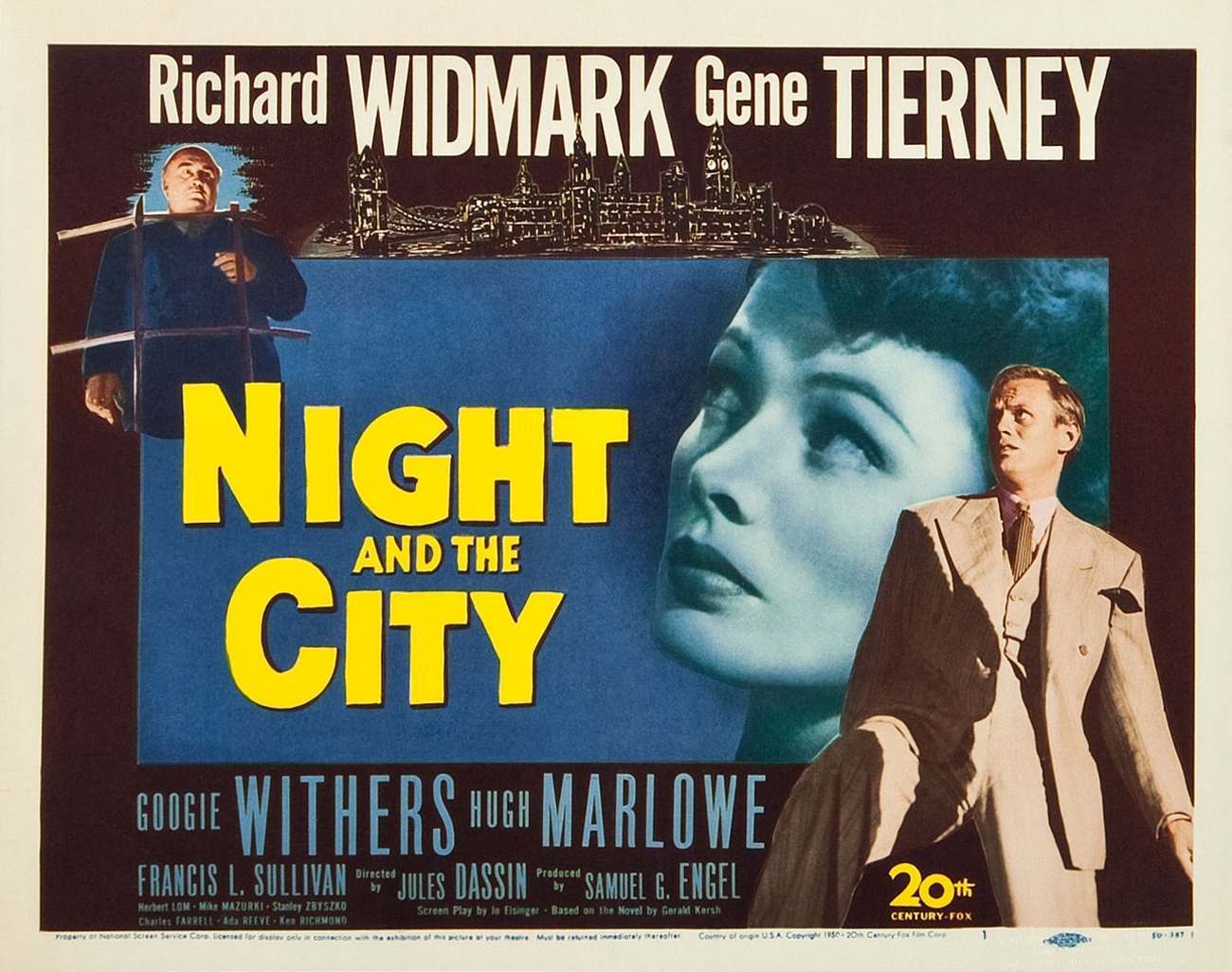

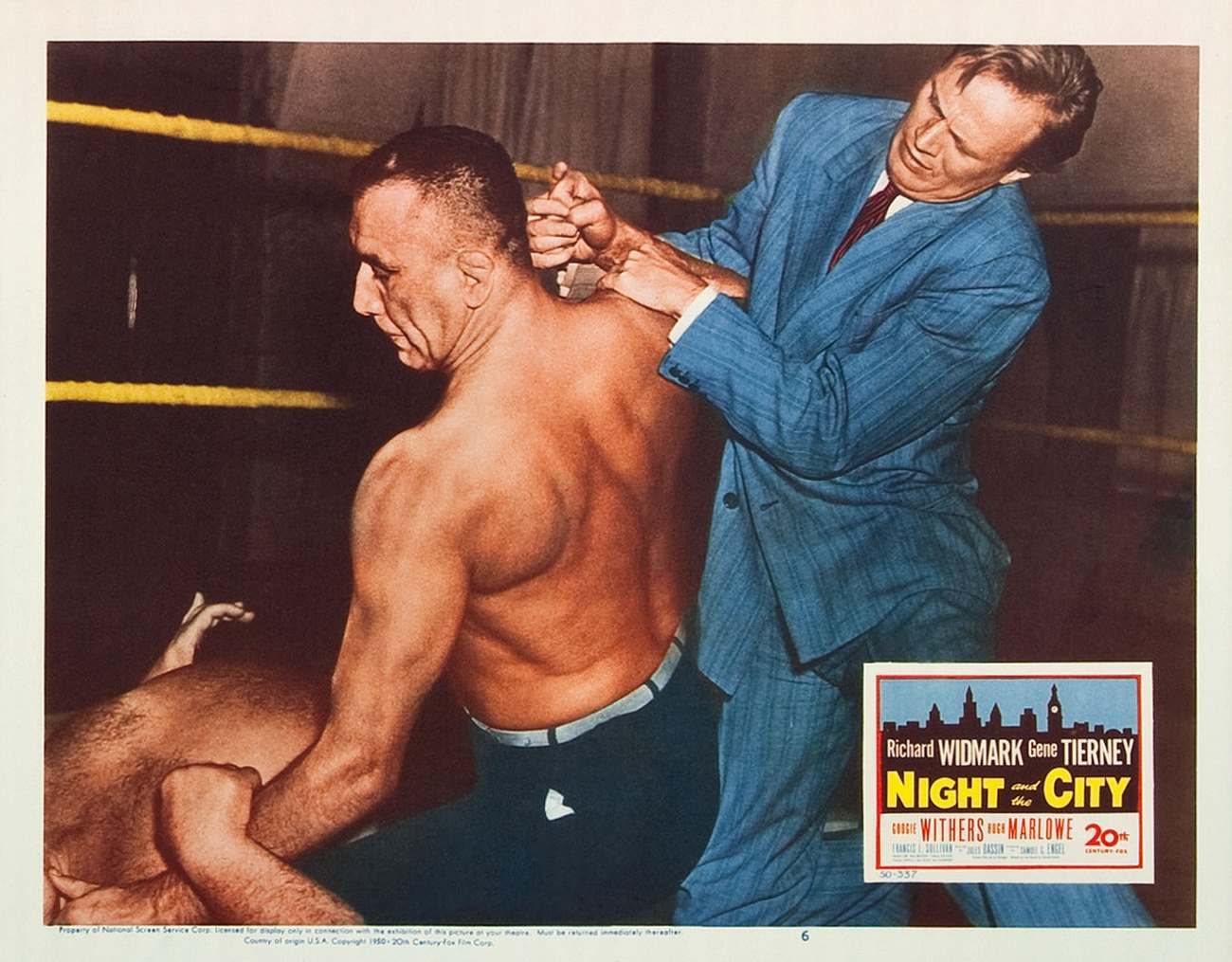

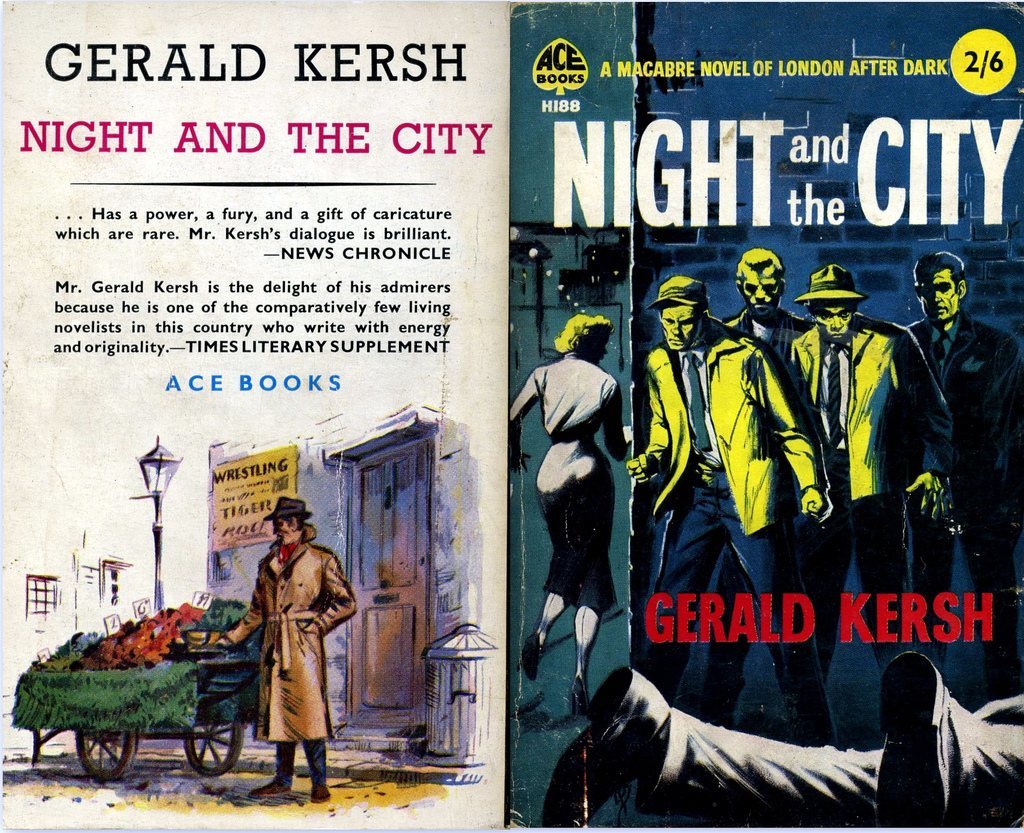

Jules Dassin’s Night and the City, released in 1950, is maybe the only film where a spiv is actually the lead character. Richard Widmark’s beautifully dressed Harry Fabian is seen desperately trying to find a way to “live the life of ease and plenty” without working for it. Unfortunately the doomed exploits of Fabian was to be the last hurrah for the cinematic spiv. Post-war austerity and the accompanying rationing were the reasons why spivs existed and during the General Elections of 1950 and 1951 the Conservative Party actively campaigned on a manifesto of ending rationing as quickly as possible.

Night and the City: A revisit of the British noir’s iconic film locations

Night and the City was disliked by the British critics and also performed poorly at the box-office. Equity wrote to the government about the film criticising its use of American stars but also that the look of the film would only encourage American tourists to visit Paris instead of London. When viewed today Night and the City’s background is almost the star of the film and made up of rubble-strewn bomb-sites that went on to scar the capital city for decades. In 1950, for critics and the public alike, it was almost the last thing they wanted to see. Although C.A. Lejeune of the Observer spent a long time in her review noting how preposterous it was that Harry Fabian managed to run from Waterloo to Hammersmith in ‘ten minutes’, she left enough space to ensure her readers that she was left as unimpressed with Night and the City as she was with Brighton Rock three years earlier:

Thieves, drabs and trollops haunt its reeking dens, monstrously distorted figures, shot from a “worm’s-eye or bird’s-eye view, slink in and out of its shadows. “The things I did!” – moans Richard Widmark, the hero, before he expires, but it is almost impossible to see the things he did, such monumental murk lies over the picture.

The issuing of petrol coupons ended in May 1951 but when the Conservatives won the General Election in October that same year it was the beginning of the end of all rationing. Sugar became free to buy in 1952 and when in July 1954 the public were allowed to buy meat wherever and whenever they wanted it brought an end to government-imposed rationing completely. Members of the London Housewives’ Association held a ceremony in Trafalgar Square to mark ‘Derationing Day’ and the Minister of Fuel and Power, Geoffrey Lloyd burned a rationing book at a public meeting in his constituency.

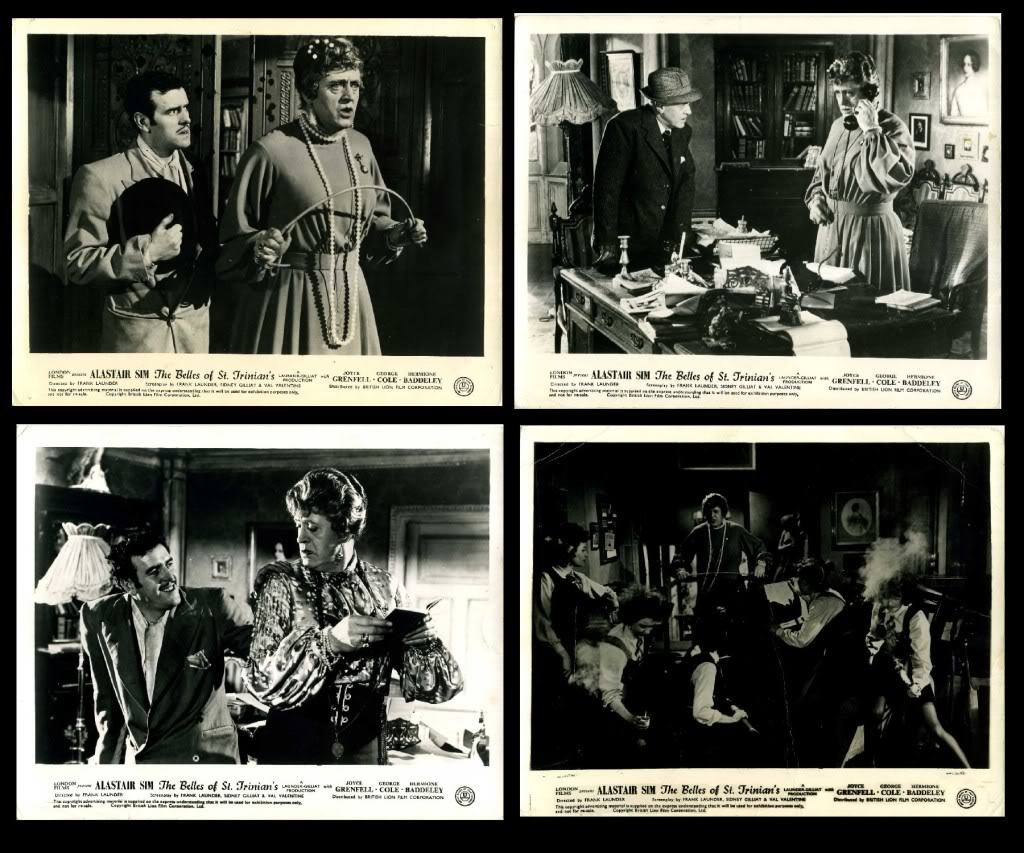

The spivs slowly withdrew from view and the close sympathetic relationship between the public and the flashy small-fry criminals came to an end. Three months after the last ration book was used the film Belles of St Trinian’s was released and introduced to the world the over-the-top spiv character called Flash Harry played by George Cole. Almost over night the spivs had become but a joke.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.