To help us to understand our own minds, Swiss psychiatrist-psychoanalyst Carl Jung (July 26, 1875–June 6, 1961) invited us to play a word association game. Jung’s “Association Method” first appeared in the American Journal of Psychology in April 1910. British philosopher Alain de Botton, tells us how it worked:

“Doctor and patient were to sit facing one another, and the doctor would read out a list of one hundred words. On hearing each of these, the patient was to say the first thing that came into their head… [they must ] try never to delay speaking and that they strive to be extremely honest in reporting whatever they were thinking of, however embarrassing, strange, or random it might seem.”

First answers only, then. No contrivance. No trying to gear you thoughts to your audience, whether to please, bore or alarm. Nothing should be deliberate. Give full throat to your freedom of expression and gut. This is about finding out what you really think. And what you discover might be unsettling. As Margaret Heffernan notes in Willful Blindness: Why We Ignore the Obvious at Our Peril, there are moments where “we could know, and should know, but don’t know because it makes us feel better not to know.”

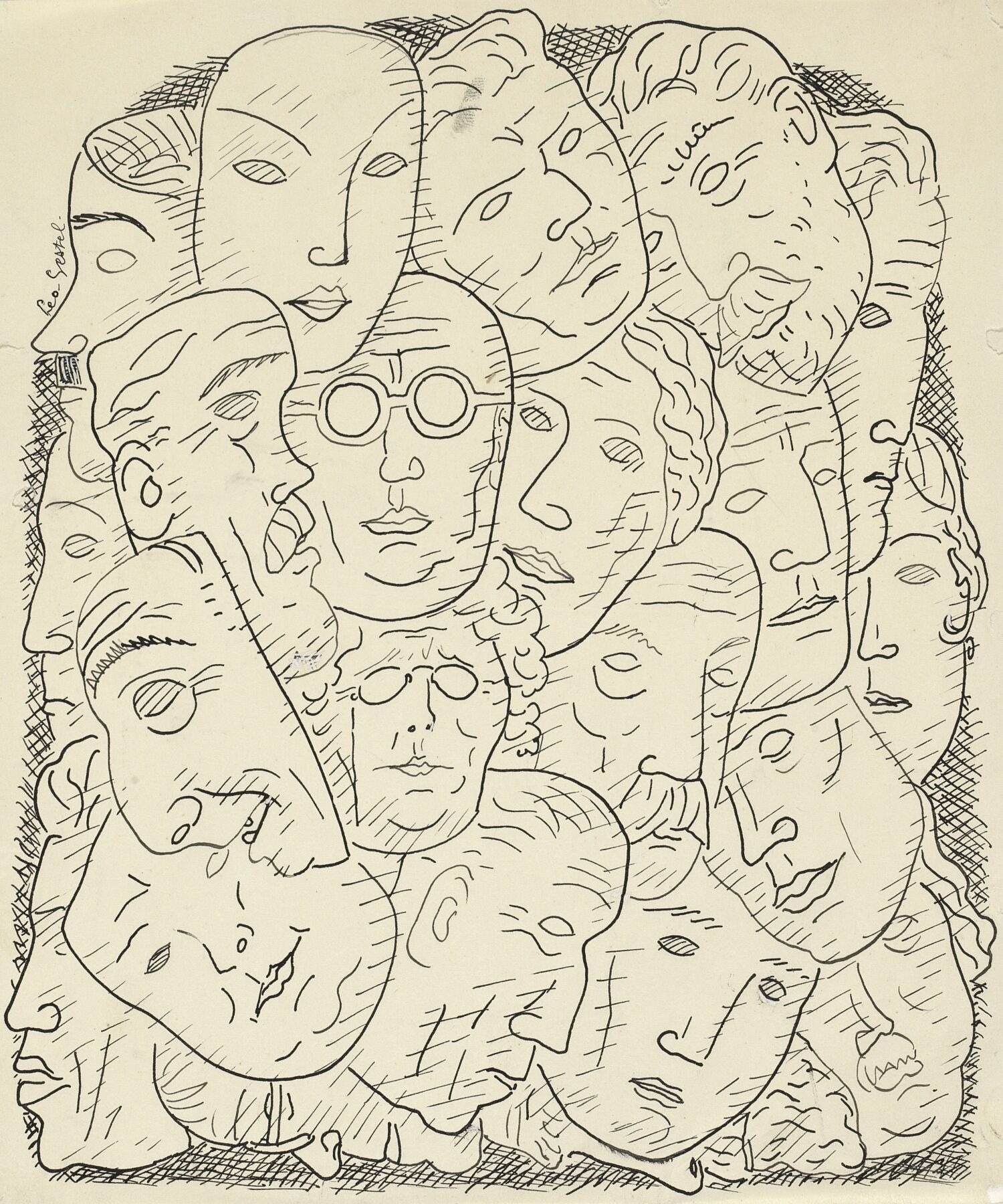

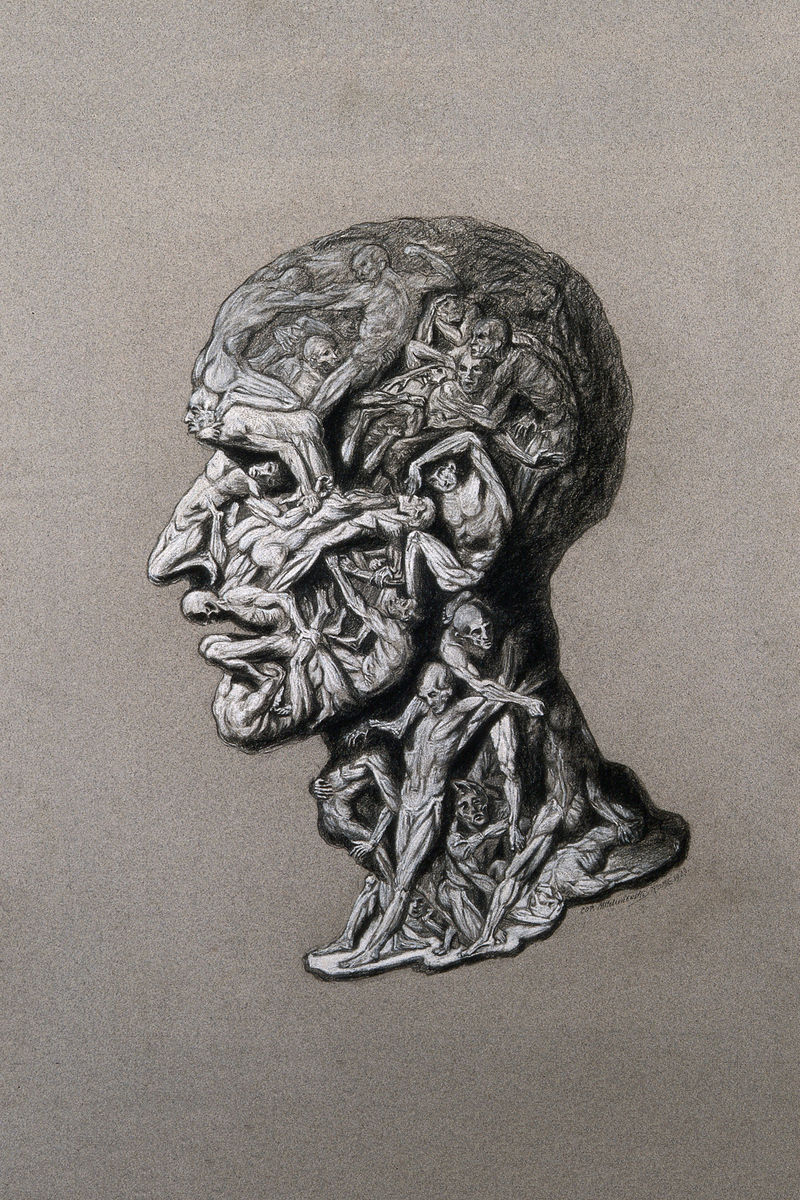

The Head of a Man Composed of Writhing Nude Figures by Hans Mischlenski – 1929. The Head of a Man Composed of Writhing Nude Figures by Hans Mischlenski – 1929. Buy the print.

Jung wanted to know. For him the human psyche was a profound reality. The truth was in there, whether you liked it or not. And through knowing our subconscious we can grow out conscious selves. As he wrote in Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

“As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being. It may even be assumed that just as the unconscious affects us, so the increase in our consciousness affects the unconscious.”

Jung was sure he and his colleagues “had hit upon an extremely simple yet highly effective method for revealing parts of the mind that were normally relegated to the unconscious. Patients who in ordinary conversation would make no allusions to certain topics or concerns would, in a word association session, quickly let slip critical aspects of their true selves.”

The words make a verbal strike to the subconscious, much like how a knock on the patellar tendon with a reflex hammer tiggers your knee to jerk. No thought. Just automatic response. Jung explained further:

“When the experiment is finished I first look over the general course of the reaction times. Prolonged times [mean] the patient can only adjust himself with difficulty, that his psychological functions proceed with marked internal frictions, with resistances.”

Jung learned that “it was precisely where there were the longest silences that the deepest conflicts and neuroses lay.”

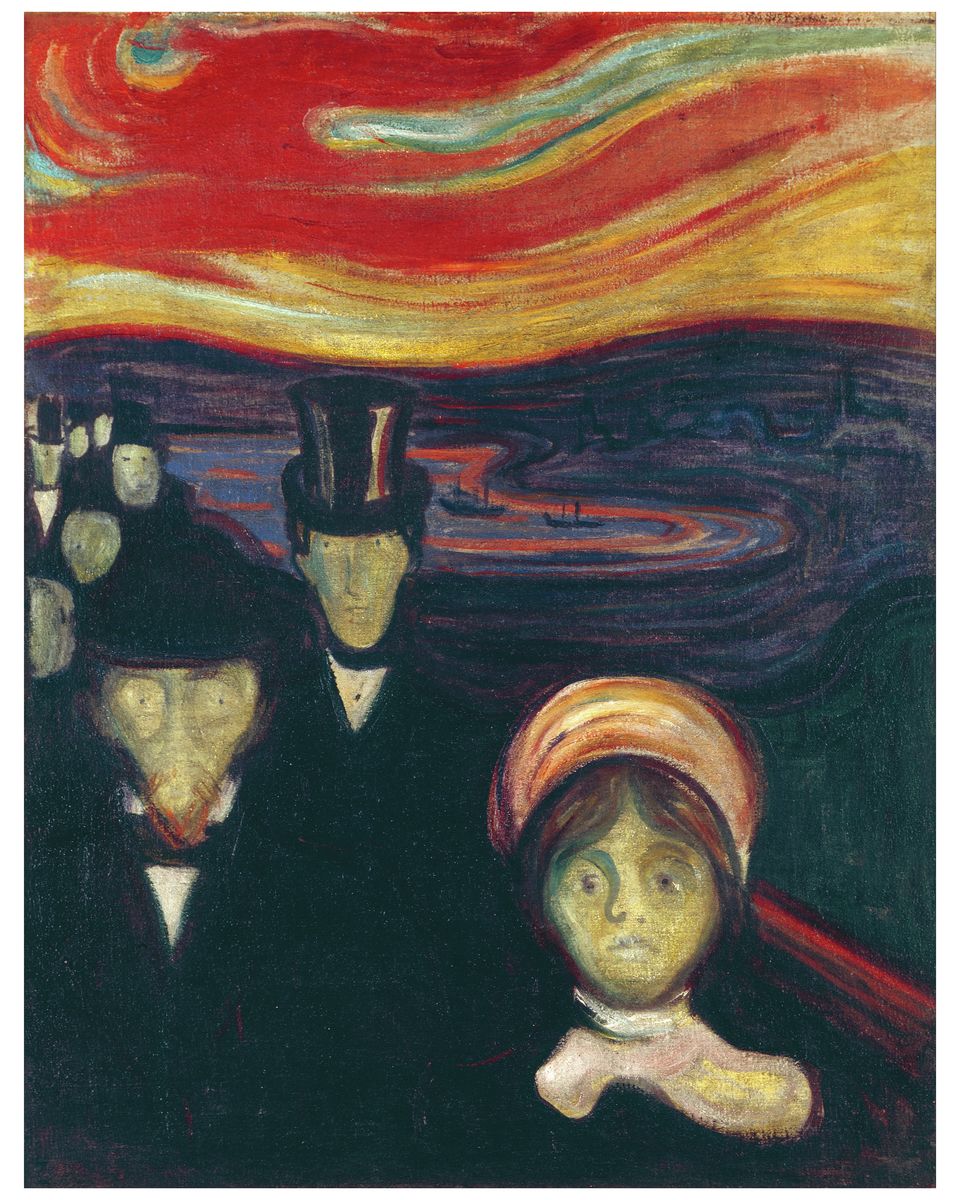

Anxiety by Edvard Munch – 1894. Buy the print.

As for the choice of words to use, each one on the list of 100 had been tried and tested, and their location in the list honed. “As a rule it is well to follow up the critical words by indifferent words in order that the action of the first may be clearly distinguished,” Jung wrote. “But one may also follow up one critical word by another, especially if one wishes to bring into relief the action of the second.”

Test and test again. But does the testing ever end? Surely, it can never be perfect? He wrote:

“This formulary has been constructed after many years of experience. The words are chosen and partially arranged in such a manner as to strike easily almost all complexes of practical occurrence… there is a regular mixing of the grammatical qualities of the words. This, too, has its definite reasons.

“Before the experiment begins the test person receives the following instruction: ‘Answer as quickly as possible the first word that occurs to your mind.’ This instruction is so simple that it can easily be followed by anybody. The work itself, moreover, appears extremely easy, so that is might be expected that any one could accomplish it with the greatest facility and promptitude. But contrary to expectation the behavior is quite different.”

And to Jung and his experiment, the words are not static. They are alive and serve as substitutes for the real thing they represent.

“Words are really something like condensed actions, situations, and things. When I present a word to the test person which denotes an action it is the same as if I should present to him the action itself, and ask him, ‘How do you behave towards it? What do you think of it? What do you do in this situation?’ If I were a magician I should cause the situation corresponding to the stimulus word to appear in reality and placing the test person in its midst, I should then study his manner of reaction.”

So how would you visualise “pity” or “to take care”, or any other more abstract ideas on Jung’s list? Words are not simply objects but possess their own power. They suggest much. Does the reaction differ if you vary how they’re said – loud or soft? Quick fire or slow and deliberate?

“…as we are not magicians we must be contented with the linguistic substitutes for reality; at the same time we must not forget that the stimulus word will as a rule always conjure up its corresponding situation. It all depends on how the test person reacts to this situation. The situation ‘bride’ or ‘bridegroom’ will not evoke a simple reaction in a young lady; but the reaction will be deeply influenced by the provoked strong feeling tones, the more so if the experimenter be a man.”

Jung adds that delays in reaction times are the product of some “disease,” and “we are dealing with a psychoneurosis, with a functional disturbance of the mind.” Is it always the case that delay equates to imperfection? Isn’t it just rational deliberation creeping into the test? And isn’t an innate desire to rationalise no less automatic than a guterral reply? “Some find that too many ideas suddenly occur to them, others, that not enough ideas come to their minds,” he wrote. “In most cases, however, the difficulties first perceived are so deterrent that they actually give up the whole reaction.”

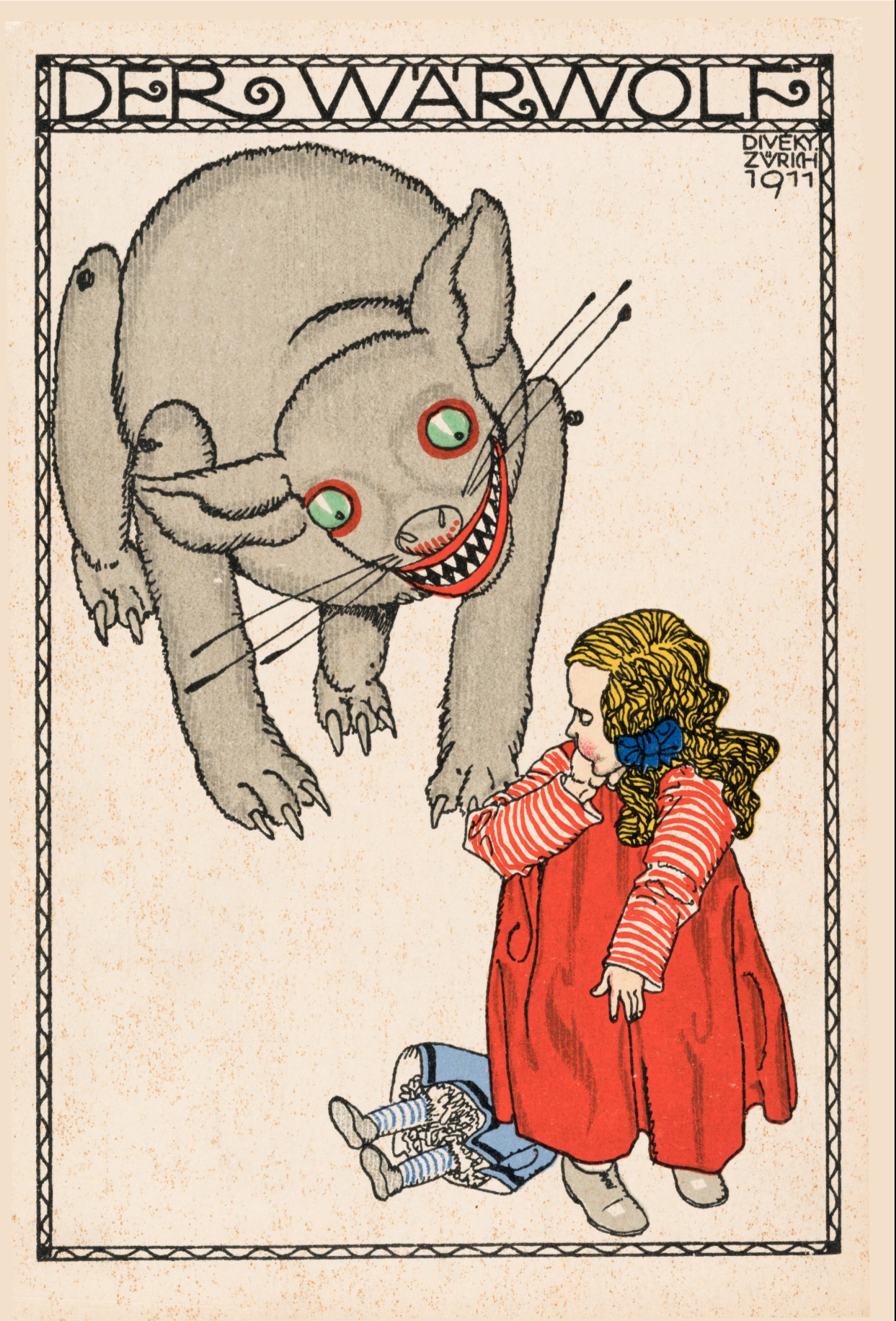

The Werewolf by Josef von Diveky for Wiener Werkstätte Nr. 497, 1911 – buy the card.

Here are the list of Jung’s words. Say the very first thing that comes into your head in response each one. Then consider your answers and bow they compare and contrast to your everyday thoughts:

1. head

2. green

3. water

4. to sing

5. dead

6. long

7. ship

8. to pay

9. window

10. friendly

11. to cook

12. to ask

13. cold

14. stem

15. to dance

16. village

17. lake

18. sick

19. pride

20. to cook

21. ink

22. angry

23. needle

24. to swim

25. voyage

26. blue

27. lamp

28. to sin

29. bread

30. rich

31. tree

32. to prick

33. pity

34. yellow

35. mountain

36. to die

37. salt

38. new

39. custom

40. to pray

41. money

42. foolish

43. pamphlet

44. despise

45. finger

46. expensive

47. bird

48. to fall

49. book

50. unjust

51 frog

52. to part

53. hunger

54. white

55. child

56. to take care

57. lead pencil

58. sad

59. plum

60. to marry

61. house

62. dear

63. glass

64. to quarrel

65. fur

66. big

67. carrot

68. to paint

69. part

70. old

71. flower

72. to beat

73. box

74. wild

75. family

76. to wash

77. cow

78. friend

79. luck

80. lie

81. deportment

82. narrow

83. brother

84. to fear

85. stork

86. false

87. anxiety

88. to kiss

89. bride

90. pure

91. door

92. to choose

93. hay

94. contented

95. ridicule

96. to sleep

97. month

98. nice

99. woman

100. to abuse

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.