The Alabama-born Tallulah Bankhead disembarked at Southampton from the RMS Majestic, then the largest ship in world, on 13 January 1923 just over two weeks before her 21st birthday. For some reason and despite his seniority, the Chief Immigration Officer, the splendidly named Brodôme Edmund Reeve-Jones, made it his job to interview the beautiful young actress on her first visit to the United Kingdom. He had no idea who she was however – at that time she had had some small parts in a few silent films and appeared on stage in New York where, although her acting was sometimes praised, the plays themselves were all commercially and critically unsuccessful. Reeve-Jones noted down, “she explained that her father was one of the American House of Representatives and had given her money to come over and see England, that she had no occupation and did not know how long she would stay or where.” Reeve-Jones then interviewed a steward from the ship and wrote that he, “confirmed my suspicion that she was not travelling on a liner for the first time and made male friends very quickly…”

Tallulah travelled to London by train and was met at Paddington station by the theatre manager and impresario Charles B. Cochran. Known to his friends as ‘Cockie’ he was also referred to as ’the English Ziegfied’ and while the American Florenz Ziegfeld Jr had his famous ‘Ziegfeld Girls’, Cochran had the polite equivalent ‘Cochran’s Young Ladies’ many of whom became huge stars and he was or would be responsible for discovering Gertrude Lawrence, Jessie Matthews, Evelyn Laye, Hermione Baddeley, Beatrice Lillie and many, many others.

Johnston-Tallulah.Bankhead

Cochran had first met Tallulah a few weeks before in New York, at a party held by Frank Crowninshields, the editor of Vanity Fair, and he was immediately impressed with her vitality and character but particularly noted her long blonde hair – “unbanned, unwrapped it fell to my knees” Tallulah once described it. The actress told him that the uncommon sheen came from washing it solely in Energine dry-cleaning fluid. Six weeks later, now back in the UK, Cochran sent her a cable: POSSIBLE ENGAGEMENT WITH GERALD DU MAURIER IN ABOUT EIGHT WEEKS. The message was soon followed by a letter:

My dear Tallulah,

This is the position.

Sir Gerald du Maurier is producing in about eight weeks’ time a new play. The part-authoress [the actress Viola Tree, daughter of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree and niece of Max Beerbohm] tells me that there are two good women parts in it, one an American, the other an English girl. She tells me, and Sir Gerald confirms this, that the American is the better of the two parts. She is, I understand, somewhat of a siren and in once scene has to dance. She must be a lady, and altogether sounds like you. She is, in the play, supposed to be of surpassing beauty. I have told the part-authoress and Sir Gerald that I believe you are “the goods.”

English theatrical producer Charles B. Cochran aboard the liner Berengaria in 1928, joined by his wife, composer Sir Noel Coward, and three dancers

Cochran promised to pay her expenses if she managed to get over to London. Tallulah cabled back that she would come immediately. Cochran, however, quickly sent another telegram: TERRIBLY SORRY, DU MAURIER’S PLANS CHANGED’. Tallulah returned with: I’M COMING ANYHOW!’ with which he replied: DON’T, THERE’S A DEPRESSION HERE. IT’S VERY BAD’. Tallulah made the decision to pretend that she hadn’t received this final missive and sailed to England anyway.

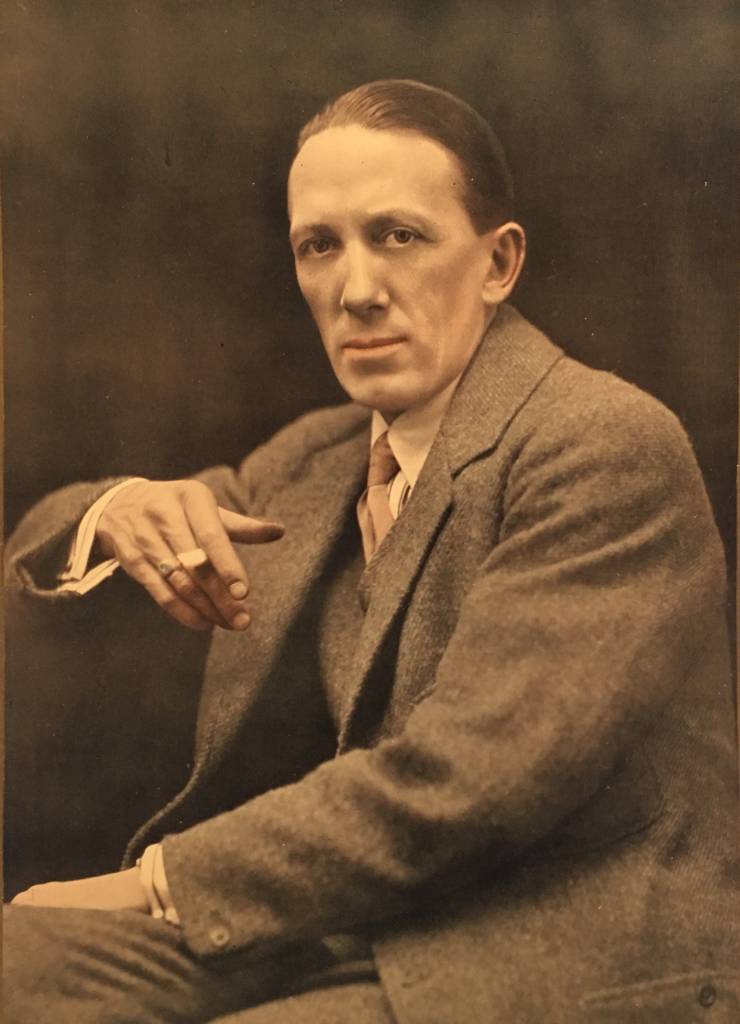

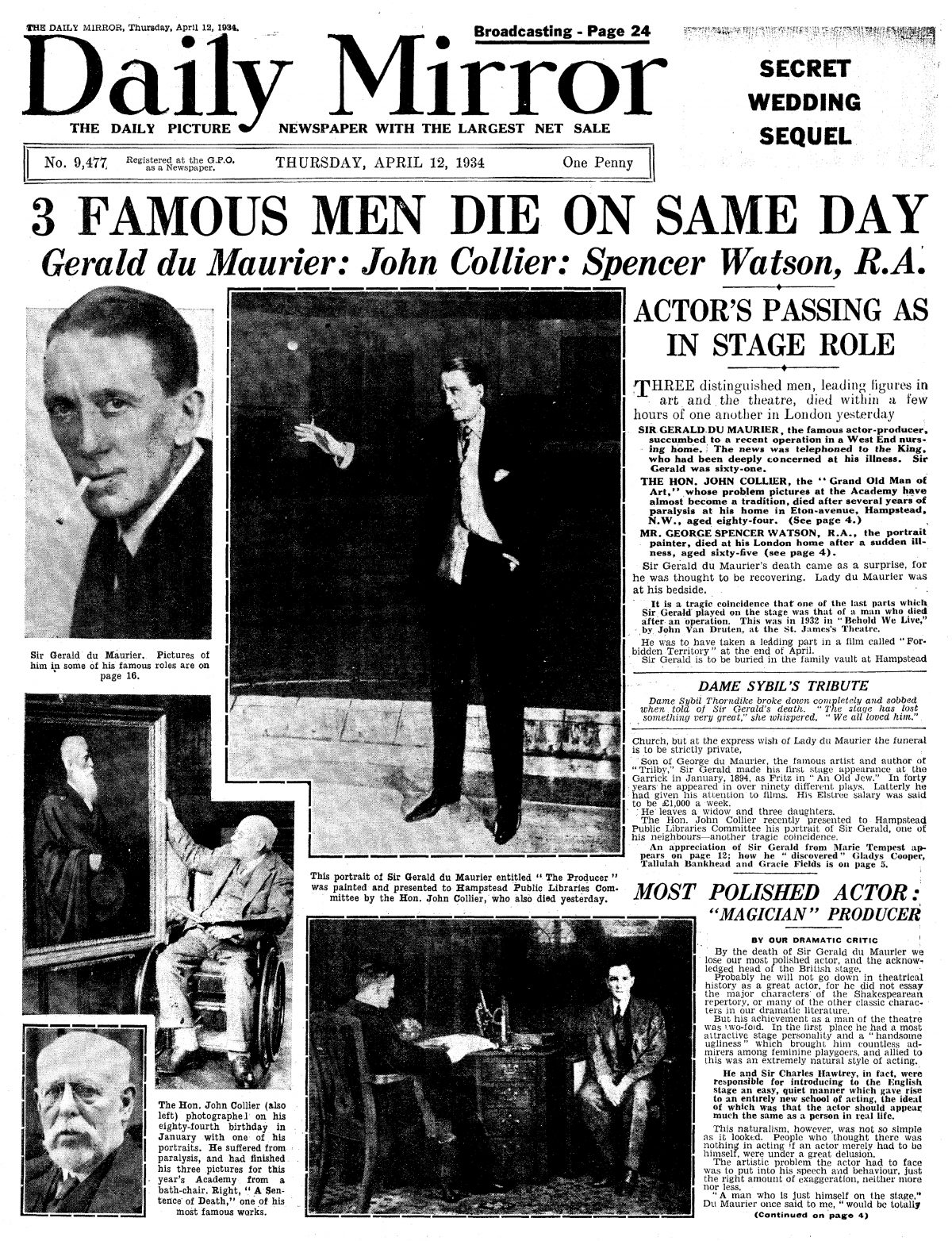

After meeting Tallulah at Paddington Cochran installed her at the Ritz and then the next day took her to Wyndham’s Theatre on Charing Cross Road. Sir Gerald du Maurier was performing in a matinee of Bulldog Drummond a play that he had adapted with H.C. McNeile, the author of the original popular novel. Du Maurier, knighted the previous year, was the son of George du Maurier the famous Punch artist and author of the best-selling novel Trilby, but also, of course, the father of the author Daphne du Maurier. Not only that, his sister Sylvia Llewelyn Davies was the mother of the boys who were the inspiration for the Peter Pan stories by J.M. Barrie.

Success had come pretty easily to Gerald, although he had no formal training or even been to drama school. He was probably the most naturally-gifted actor of his era and incredibly influential. The Times later wrote about his career, “His parentage assured him of engagements in the best of company to begin with; but it was his own talent that took advantage of them. His initial popularity became assured, however, because of his performances in two J.M. Barrie plays – the Hon. Ernest Wooley in The Admirable Crichton and the two roles of George Darling and Captain Hook in Peter Pan at the Duke of York’s Theatre in 1904. These successes were then followed by ‘his exquisitely suave presentation’of “Raffles”. It cannot be coincidence that these plays and roles with which he was associated are still remembered and often performed today.

Du Maurier’s naturalistic, almost off-hand acting style made the mannered and melodramatic style of his predecessors and, indeed, many of his contemporaries suddenly seem terribly old-fashioned. The famed matinee idol’s voice was quiet, conversational and understated. What seemed like an utter absence of technique, however, needed huge amounts of rehearsal and he would practice for hours smoking and drinking in front of mirrors. ‘Don’t force it, don’t be self-conscious,’ he would say. ‘Do what you generally do any day of your life when you come down into a room. Bite your nails, yawn, lie down on a sofa and read a book, do anything or nothing but don’t look dramatically at the audience.”

Gerald de Maurier, at Cannon Hall, Hampstead, with his two daughters, Jeanne and the teenage Daphne at about the time Tallulah was appearing with Gerald in The Dancers.

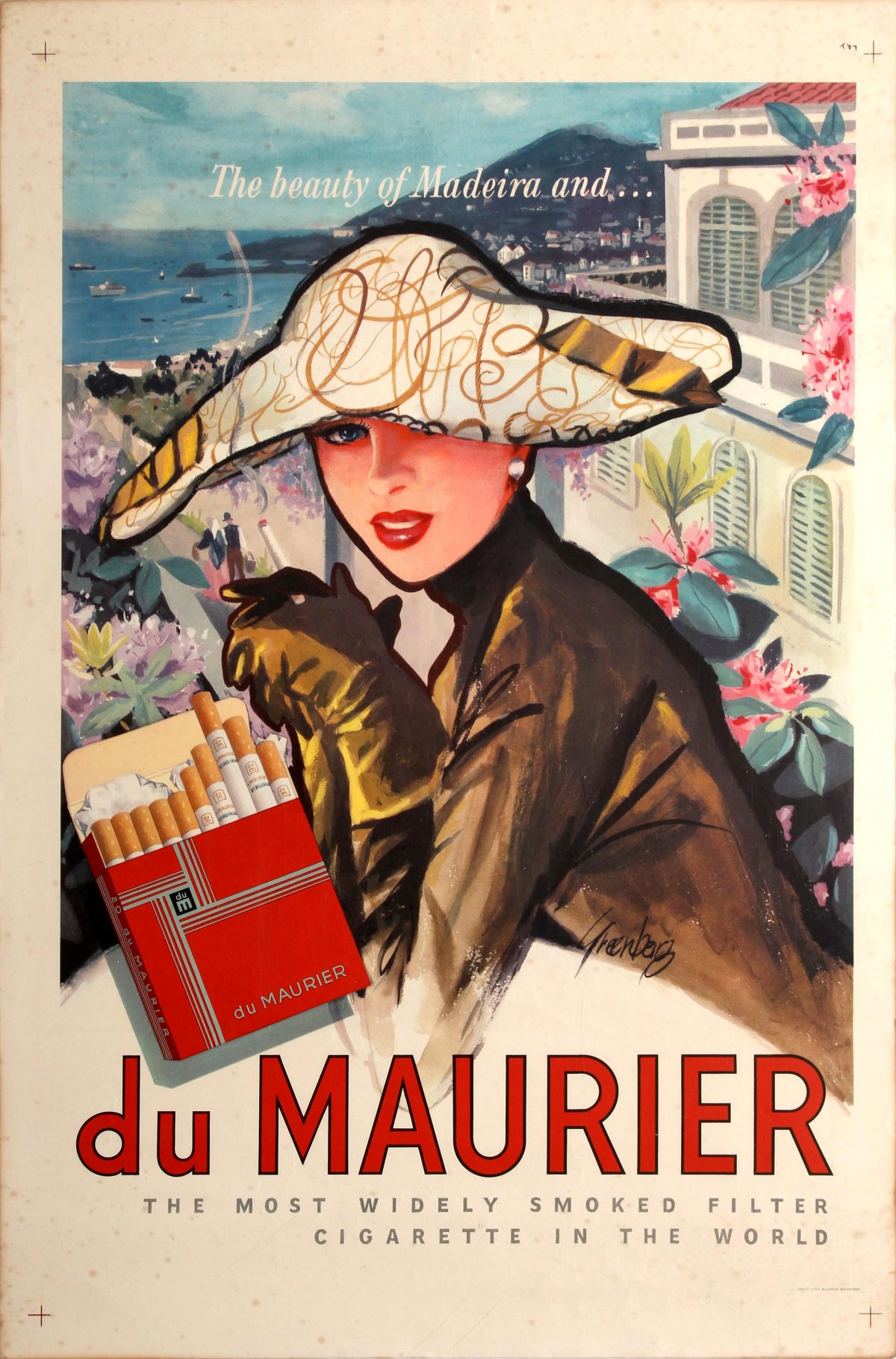

According to his daughter Daphne, Gerald hated ‘ardent lovemaking in the theatre’, “Must you kiss her as though you were having steak and onions for lunch? It may be what you feel but it’s damned unattractive from the front row of the stalls. Can’t you just say, ‘I love you’, and yawn, and light a cigarette and walk away?” Cigarettes were forever associated with du Maurier’s naturalistic acting style and in 1929 after being as blasé with his inland revenue paperwork as the was making love on stage, he earned extra money in 1929 lending his name to a brand of cigarettes – “the du Maurier filter tip gives a cool clean smoke with no loose bits in the mouth,” stated an advert of the time. Du Maurier, however, presumably preferred bits of tobacco in his mouth and always smoked filterless cigarettes which, probably, at the age of sixty-one, contributed to the cancer that killed him. His name lives on, however, and the cigarettes are still being made in Canada to this day by Imperial Tobacco.

Brilliant and skilful actor though he was du Maurier was unable to disguise his shock when Tallulah appeared in his dressing room after his afternoon performance in Bulldog Drummond. ‘Here I am!’ she said. “But we cabled you not to come,” du Maurier replied, ‘another girl has been engaged for the part. I’m terribly sorry. We’re opening in a fortnight, you know.” “Well,” replied Tallulah, ”I’m terribly sorry too, but I’m happy to be in England. It’s been a great pleasure to meet you – perhaps she’ll break a leg, or something!”

Cochran knew du Maurier well, and aware of his notorious roving-eye, and after some thought and admiring Tallulah’s bravura suggested to her that she visited the actor-manager again but this time dressed without headwear. “I don’t think he’s aware of your unusual beauty. Your hat masks your extraordinary hair.” Two days later they revisited Sir Gerald’s dressing room this time with Tallulah’s long, beautiful locks revealed. There were a few people in the room including Daphne, Gerald’s 15 year old daughter, who after Tallulah had left turned to her father and said, “Daddy, that’s the most beautiful girl I ever saw in my life.” Gerald, not entirely disagreeing with Daphne, called the American actress the next day and signed her for the part of Maxine in the play called The Dancers. Tallulah was to be paid 30 pounds per week and it was to preview in only two weeks…

Tallulah Bankhead Dorothy Wilding c.1925

Almost exactly a month after Tallulah had arrived in London, The Dancers, billed as ‘a melodrama in four parts’ opened on 15 February 1923. Presumably because the plot was more than preposterous the author of the play, Hubert Parson, was actually a joint pen-name for du Maurier himself and his friend the actress Viola Tree. Viola like Gerald had an interesting family-tree. She was born in London, the eldest of three daughters of Herbert Beerbohm Tree and his wife, the actress Helen Maud Tree, née Holt. Her aunt was author Constance Beerbohm and an uncle was Max Beerbohm. Her sisters were Felicity Tree and Iris Tree. She also had seven illegitimate half-siblings, the products of her father’s many infidelities, among them the director Carol Reed and Peter Reed, whose son became the actor Oliver Reed.

Preposterous in plot it may have been but The Dancers was an immediate success and in the end ran for thirty-four weeks. Tallulah, who had taken the rehearsals so seriously she had given up smoking so as not to get breathless in the dancing scenes, was the clear attraction – the most famous scene in the play was one in which she performed an Indian dance (Tallulah described it as an ‘Alabama variation of Minnehaha!) costumed in feathers and jewels. Her unique and exotic voice (the actor-writer Emlyn Williams described it as: “steeped as deep in sex as the human voice can go without drowning”) and unusual beauty helped her to be, almost literally, as far as London was concerned, an overnight sensation.

Hannen Swaffer, the eminent journalist, turned up at the première of The Dancers wearing a black cloak and wide-brimmed hat and wrote in the Daily Express, ‘Tallulah is the essence of sophistication…she gives electric shocks! Sex oozes from her eyes! She is daring and friendly and rude and nice, and all at once!’. Reginald Arkell, the scriptwriter and comic novelist wrote, “Everybody knows that Tallulah is one of those girls who could lure a Scotch elder into any indiscretion. Positively! Her lips are as scarlet as a guardsman’s coat, and her diamonds make the flashing signs of Piccadilly look like farthing dips. She plays “He loves me, he loves me not” with pearls that are as big as potatoes.”

Talullah Bankhead and Toto Koopman at the premiere of the film The Private Life of Don Juan in England, September 1934

Tallulah spent the next eight years in the capital in plays of various quality and success. In her own words she said: “Have I daily hinted that I cut a great swathe in London? Well I damned well did, and it was all a spur to my ego, electrifying! London beaux clamoured for my company…I created quite a stir wherever I went. I rejoiced in this harm scrum attention to the hilt, perhaps a little beyond the hilt!”

As the decade was coming to an end Tallulah knew it was time to go back home. She had no money and had always spent more than she earned. Viola Tree, the co-writer of Tallulah’s first play in London later wrote:

When first I saw Tallulah at a rehearsal of The Dancers she was a pretty American, a raw and somewhat buxom girl. Now she’s a slim, thoughtful, almost too vital woman. She had green dowdy clothes and wore a rat’s-tail fur when she landed here. But she must stay at the Ritz. She has Ritzed it ever since. This is typical of her. She earns a larger and larger salary and spends it all.

In the autumn of 1930 she received an extraordinary offer from Paramount Pictures who were willing to pay her 5000 dollars a week. It was an an amount she could hardly refuse, and she didn’t. Tallulah wrote in her autobiography: ‘Professionally I had advanced from comparative obscurity to international recognition. Fiscally I had receded. I had a letter of credit for a thousand dollars on my arrival; on my departure I had less. I left a lot of debts behind me.

Paramount weren’t the only studio at the beginning of the ‘Talkies’ era in signing up every attractive stage star they could find. Tallulah even came with a husky, seductive voice as part of the package. “Hollywood for me I’m afraid,” she said in a letter to her father. At the end of 1930 she sold her house in Farm Street in Mayfair (telephone GROvnor 1658) and with her friends Kenneth and Audry Carten, Elizabeth Lock and her latest secretary-cum-companion Dola Cavendish she travelled by train via Waterloo to Southampton. Almost exactly eight years after she had arrived in England for the first time and just before she got on the New York bound RMS Aquitania she read out a statement to the press that ended – “I’ve never had a good part yet.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.